Read Book Captain Scott Ebook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Landscapes of Exploration' Education Pack

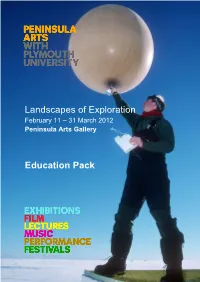

Landscapes of Exploration February 11 – 31 March 2012 Peninsula Arts Gallery Education Pack Cover image courtesy of British Antarctic Survey Cover image: Launch of a radiosonde meteorological balloon by a scientist/meteorologist at Halley Research Station. Atmospheric scientists at Rothera and Halley Research Stations collect data about the atmosphere above Antarctica this is done by launching radiosonde meteorological balloons which have small sensors and a transmitter attached to them. The balloons are filled with helium and so rise high into the Antarctic atmosphere sampling the air and transmitting the data back to the station far below. A radiosonde meteorological balloon holds an impressive 2,000 litres of helium, giving it enough lift to climb for up to two hours. Helium is lighter than air and so causes the balloon to rise rapidly through the atmosphere, while the instruments beneath it sample all the required data and transmit the information back to the surface. - Permissions for information on radiosonde meteorological balloons kindly provided by British Antarctic Survey. For a full activity sheet on how scientists collect data from the air in Antarctica please visit the Discovering Antarctica website www.discoveringantarctica.org.uk and select resources www.discoveringantarctica.org.uk has been developed jointly by the Royal Geographical Society, with IBG0 and the British Antarctic Survey, with funding from the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. The Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) supports geography in universities and schools, through expeditions and fieldwork and with the public and policy makers. Full details about the Society’s work, and how you can become a member, is available on www.rgs.org All activities in this handbook that are from www.discoveringantarctica.org.uk will be clearly identified. -

The South Polar Race Medal

The South Polar Race Medal Created by Danuta Solowiej The way to the South Pole / Sydpolen. Roald Amundsen’s track is in Red and Captain Scott’s track is in Green. The South Polar Race Medal Roald Amundsen and his team reaching the Sydpolen on 14 Desember 1911. (Obverse) Captain R. F. Scott, RN and his team reaching the South Pole on 17 January 1912. (Reverse) Created by Danuta Solowiej Published by Sim Comfort Associates 29 March 2012 Background The 100th anniversary of man’s first attainment of the South Pole recalls a story of two iron-willed explorers committed to their final race for the ultimate prize, which resulted in both triumph and tragedy. In July 1895, the International Geographical Congress met in Lon- don and opened Antarctica’s portal by deciding that the southern- most continent would become the primary focus of new explora- tion. Indeed, Antarctica is the only such land mass in our world where man has ventured and not found man. Up until that time, no one had explored the hinterland of the frozen continent, and even the vast majority of its coastline was still unknown. The meet- ing touched off a flurry of activity, and soon thereafter national expeditions and private ventures started organizing: the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration had begun, and the attainment of the South Pole became the pinnacle of that age. Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen (1872-1928) nurtured at an early age a strong desire to be an explorer in his snowy Norwegian surroundings, and later sailed on an Arctic sealing voyage. -

Antarctica: Music, Sounds and Cultural Connections

Antarctica Music, sounds and cultural connections Antarctica Music, sounds and cultural connections Edited by Bernadette Hince, Rupert Summerson and Arnan Wiesel Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Antarctica - music, sounds and cultural connections / edited by Bernadette Hince, Rupert Summerson, Arnan Wiesel. ISBN: 9781925022285 (paperback) 9781925022292 (ebook) Subjects: Australasian Antarctic Expedition (1911-1914)--Centennial celebrations, etc. Music festivals--Australian Capital Territory--Canberra. Antarctica--Discovery and exploration--Australian--Congresses. Antarctica--Songs and music--Congresses. Other Creators/Contributors: Hince, B. (Bernadette), editor. Summerson, Rupert, editor. Wiesel, Arnan, editor. Australian National University School of Music. Antarctica - music, sounds and cultural connections (2011 : Australian National University). Dewey Number: 780.789471 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover photo: Moonrise over Fram Bank, Antarctica. Photographer: Steve Nicol © Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2015 ANU Press Contents Preface: Music and Antarctica . ix Arnan Wiesel Introduction: Listening to Antarctica . 1 Tom Griffiths Mawson’s musings and Morse code: Antarctic silence at the end of the ‘Heroic Era’, and how it was lost . 15 Mark Pharaoh Thulia: a Tale of the Antarctic (1843): The earliest Antarctic poem and its musical setting . 23 Elizabeth Truswell Nankyoku no kyoku: The cultural life of the Shirase Antarctic Expedition 1910–12 . -

The Antarctican Society 905 North Jacksonville Street Arlington, Virginia 22205 Honorary President — Ambassador Paul C

THE ANTARCTICAN SOCIETY 905 NORTH JACKSONVILLE STREET ARLINGTON, VIRGINIA 22205 HONORARY PRESIDENT — AMBASSADOR PAUL C. DANIELS ________________________________________________________________ Presidents: Vol. 85-86 November No. 2 Dr. Carl R. Eklund, 1959-61 Dr. Paul A. Siple, 1961-2 Mr. Gordon D. Cartwright, 1962-3 RADM David M. Tyree (Ret.) 1963-4 Mr. George R. Toney, 1964-5 A PRE-THANKSGIVING TREAT Mr. Morton J. Rubin, 1965-6 Dr. Albert P. Crary, 1966-8 Dr. Henry M. Dater, 1968-70 Mr. George A. Doumani, 1970-1 MODERN ICEBREAKER OPERATIONS Dr. William J. L. Sladen, 1971-3 Mr. Peter F. Bermel, 1973-5 by Dr. Kenneth J. Bertrand, 1975-7 Mrs. Paul A. Siple, 1977-8 Dr. Paul C. Dalrymple, 1978-80 Commander Lawson W. Brigham Dr. Meredith F. Burrill, 1980-82 United States Coast Guard Dr. Mort D. Turner, 1982-84 Dr. Edward P. Todd, 1984-86 Liaison Officer to Chief of Naval Operations Washington, D.C. Honorary Members: Ambassador Paul C. Daniels on Dr. Laurence McKiniey Gould Count Emilio Pucci Tuesday evening, November 26, 1985 Sir Charles S. Wright Mr. Hugh Blackwell Evans 8 PM Dr. Henry M. Dater Mr. August Howard National Science Foundation Memorial Lecturers: 18th and G Streets NW Dr. William J. L. Sladen, 1964 RADM David M. Tyree (Ret.), 1965 Room 543 Dr. Roger Tory Peterson, 1966 Dr. J. Campbell Craddock, 1967 Mr. James Pranke, 1968 - Light Refreshments - Dr. Henry M. Dater, 1970 Sir Peter M. Scott, 1971 Dr. Frank T. Davies, 1972 Mr. Scott McVay, 1973 Mr. Joseph O. Fletcher, 1974 Mr. Herman R. Friis, 1975 This presentation by one of this country's foremost experts on ice- Dr. -

THE STANDARD CHARTERED TRANS-ANTARCTIC WINTER EXPEDITION SUPPORTED by the COMMONWEALTH the Coldest Journey on Earth

THE STANDARD CHARTERED TRANS-ANTARCTIC WINTER EXPEDITION SUPPORTED BY THE COMMONWEALTH The Coldest Journey On Earth PATRON: HRH THE PRINCE OF WALES, CHAIRMAN: Tony Medniuk, DEPUTY CHAIRMAN: Gavin Laws (Standard Chartered Bank), SCIENCE COMMITTEE CHAIRMAN: Sir Peter Williams CBE FRS FREng, SCIENCE COMMITTEE DEPUTY CHAIRMAN: Prof Dougal Goodman FREng, EXPEDITION ORGANISER & LEADER: Sir Ranulph Fiennes Bt OBE, MARINE ORGANISER: Anton Bowring, COMMONWEALTH LIAISON: Derek Smail, EXPEDITION POLAR PLANNER: Martin Bell, EXPEDITION POLAR CONSULTANT: Jim McNeill, INTERACTIVE EDUCATIONAL WEBSITE DIRECTOR/MICROSOFT LIAISON: Phil Hodgson (Durham's Education Development Service), EXTREME COLD TEMPERATURE EQUIPMENT: Steven Holland and Team, SPONSOR LIAISON: Eric Reynolds The TAWT TRUST Ltd (UK Registered Charity 7424188) CHAIRMAN: Tony Medniuk, DEPUTY CHAIRMAN: Gavin Laws; Michael Payton, Richard Jackson, Alan Tasker, Anton Bowring, Sir Ranulph Fiennes Bt OBE IN CONFIDENCE EXPEDITION AIMS AND OUTLINE SCHEDULE 1. OVERALL The aim of the TAWT Expedition is to complete the first historic crossing of the Antarctic Continent, to raise over £10 million for our charity SEEING IS BELIEVING, to educate school children, and to complete our science programme. In order not to alert other polar groups, such as our long-time rivals in Norway, we will only announce the Expedition when we are 100% ready to go! The earliest date that we could leave the UK will be 1 October 2012. The alternate date, given any unforeseen delay, will be 1 October 2013. Relevant Antarctic Records 1902 First Penetration of the unknown continent : Scott/Shackleton/Wilson (Brit) 1908 First Penetration of Inland icecap : Shackleton/Wilde/Marshall/?+1 (Brit) 1911 First to reach South Pole : Amundsen + 4 skiers (Norwegian) 1950s First 2-way-pincer Crossing of Antarctica. -

Rather Than Imposing Thematic Unity Or Predefining a Common Theoretical

The Supernatural Arctic: An Exploration Shane McCorristine, University College Dublin Abstract The magnetic attraction of the North exposed a matrix of motivations for discovery service in nineteenth-century culture: dreams of wealth, escape, extreme tourism, geopolitics, scientific advancement, and ideological attainment were all prominent factors in the outfitting expeditions. Yet beneath this „exoteric‟ matrix lay a complex „esoteric‟ matrix of motivations which included the compelling themes of the sublime, the supernatural, and the spiritual. This essay, which pivots around the Franklin expedition of 1845-1848, is intended to be an exploration which suggests an intertextuality across Arctic time and geography that was co-ordinated by the lure of the supernatural. * * * Introduction In his classic account of Scott‟s Antarctic expedition Apsley Cherry- Garrard noted that “Polar exploration is at once the cleanest and most isolated way of having a bad time which has been devised”.1 If there is one single question that has been asked of generations upon generations of polar explorers it is, Why?: Why go through such ordeals, experience such hardship, and take such risks in order to get from one place on the map to another? From an historical point of view, with an apparent fifty per cent death rate on polar voyages in the long nineteenth century amid disaster after disaster, the weird attraction of the poles in the modern age remains a curious fact.2 It is a less curious fact that the question cui bono? also featured prominently in Western thinking about polar exploration, particularly when American expeditions entered the Arctic 1 Apsley Cherry-Garrard, The Worst Journey in the World. -

Herbert Ponting; Picturing the Great White South

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2014 Herbert Ponting; Picturing the Great White South Maggie Downing CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/328 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The City College of New York Herbert Ponting: Picturing the Great White South Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts of the City College of the City University of New York. by Maggie Downing New York, New York May 2014 Dedicated to my Mother Acknowledgments I wish to thank, first and foremost my advisor and mentor, Prof. Ellen Handy. This thesis would never have been possible without her continuing support and guidance throughout my career at City College, and her patience and dedication during the writing process. I would also like to thank the rest of my thesis committee, Prof. Lise Kjaer and Prof. Craig Houser for their ongoing support and advice. This thesis was made possible with the assistance of everyone who was a part of the Connor Study Abroad Fellowship committee, which allowed me to travel abroad to the Scott Polar Research Institute in Cambridge, UK. Special thanks goes to Moe Liu- D'Albero, Director of Budget and Operations for the Division of the Humanities and the Arts, who worked the bureaucratic college award system to get the funds to me in time. -

Scurvy? Is a Certain There Amount of Medical Sure, for Know That Sheds Light on These Questions

J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2013; 43:175–81 Paper http://dx.doi.org/10.4997/JRCPE.2013.217 © 2013 Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh The role of scurvy in Scott’s return from the South Pole AR Butler Honorary Professor of Medical Science, Medical School, University of St Andrews, Scotland, UK ABSTRACT Scurvy, caused by lack of vitamin C, was a major problem for polar Correspondence to AR Butler, explorers. It may have contributed to the general ill-health of the members of Purdie Building, University of St Andrews, Scott’s polar party in 1912 but their deaths are more likely to have been caused by St Andrews KY16 9ST, a combination of frostbite, malnutrition and hypothermia. Some have argued that Scotland, UK Oates’s war wound in particular suffered dehiscence caused by a lack of vitamin C, but there is little evidence to support this. At the time, many doctors in Britain tel. +44 (0)1334 474720 overlooked the results of the experiments by Axel Holst and Theodor Frølich e-mail [email protected] which showed the effects of nutritional deficiencies and continued to accept the view, championed by Sir Almroth Wright, that polar scurvy was due to ptomaine poisoning from tainted pemmican. Because of this, any advice given to Scott during his preparations would probably not have helped him minimise the effect of scurvy on the members of his party. KEYWORDS Polar exploration, scurvy, Robert Falcon Scott, Lawrence Oates DECLaratIONS OF INTERESTS No conflicts of interest declared. INTRODUCTION The year 2012 marked the centenary of Robert -

Who Is Sir Ranulph Fiennes?

Who Is Sir Ranulph Fiennes? Sir Ranulph Fiennes is a British expedition leader who has broken world records, won many awards and completed expeditions on a range of different modes of transport. These include hovercraft, riverboat, manhaul sledge, snowmobile, skis and a four-wheel drive vehicle. He is also the only living person who has travelled around the Earth’s circumpolar surface. Did You Know…? Circumpolar means Sir Ranulph does not call himself to go around the an explorer as he says he has only Earth’s North Pole once mapped an unknown area. and South Pole. The Beginning of an Expedition Leader Sir Ranulph Twisleton-Wykeham-Fiennes was born on 7th March 1944 in Windsor, UK. His father was killed during the Second World War and after the war, Ranulph’s mother moved the family to South Africa. He lived there until he was 12 years old. He returned to the UK where he continued his education, later attending Eton College. Ranulph joined the British army, where he served for eight years in the same regiment that his father had served in, the Royal Scots Greys. While in the army, Ranulph taught soldiers how to ski and canoe. After leaving the army, Ranulph and his wife decided to earn money by leading expeditions. A World of Expeditions North Pole Arctic Mount Everest The Eiger The River Nile South Pole Antarctic The Transglobe Expedition In 1979, Ranulph, his wife Ginny and friends Charles Burton and Oliver Shepherd embarked on an expedition to the Antarctic which was planned by Ginny, an explorer in her own right. -

Brilliant Ideas to Get Your Students Thinking Creatively About Polar

FOCUS ON SHACKLETON Brilliant ideas to get your students thinking creatively about polar exploration, with links across a wide range of subjects including maths, art, geography, science and literacy. WHAT? WHERE? WHEN? WHO? AURORA AUSTRALIS This book was made in the Antarctic by Shackleton’s men during the winter of 1908. It contains poems, accounts, stories, pictures and entertainment all written by the men during the 1907-09 Nimrod expedition. The copy in our archive has a cover made from pieces of packing crates. The book is stitched with green silk cord thread and held together with a spine made from seal skin. The title and the penguin stamp were glued on afterwards. DID YOU KNOW? To entertain the men during the long, cold winter months of the Nimrod Expedition, Shackleton packed a printing press. Before the expedition set off Ernest Joyce and Frank Wild received training in typesetting and printing. In the hut at Cape Royds the men wrote and practised their printing techniques. All through the winter different men wrote pieces for the book. The expedition artist, George Marston, produced the illustrations. Bernard Day constructed the book using packing crates that had stored butter. This was the first book to be published in the Antarctic. SHORT FILMS ABOUT ANTARCTICA: www.spri.cam.ac.uk/museum/resources Accession number: MS 722;EN – Dimensions: height: 270mm, width 210mm, depth: 30mm MORE CLASSROOM ACTIVITIES: www.spri.cam.ac.uk/museum/resources HIGH RESOLUTION IMAGE: www.spri.cam.ac.uk/museum/resources This object is part of the collection at the Scott Polar Research Institute in Cambridge ̶ see more online at: www.spri.cam.ac.uk/collections ACTIVITY IDEAS FOR THE CLASSROOM Visit our website for a high resolution image of this object and more: www.spri.cam.ac.uk/museum/resources BACKGROUND ACTIVITY IDEA RESOURCES CURRICULUM LINKS Aurora Australis includes lots of accounts, As a class discuss events that you have all experienced - a An example of an account, poem LITERACY different styles of writing, stories and poems written by the men. -

Trans-Antarctic Winter Expedition Supported by the Commonwealth

The Seeing is Believing Trans-Antarctic Winter Expedition Supported by the Commonwealth PATRON: HRH The Prince of Wales EXPEDITION LEADER: Sir Ranulph Fiennes Bt OBE The Coldest Journey – Background 23rd November 2012 Expedition members: Brian Newham, Leader: Brian is an experienced British alpine mountaineer and advanced skier with considerable polar experience having spent more than 20 seasons in Antarctica and with nine visits to the Arctic. Aged 54, Brian has a BSc in Mechanical Engineering and has worked for the British Antarctic Survey as Field Assistant (mountaineer) and as Base Commander for Halley Station, Rothera Station and briefly at the NERC research station in Svalbard. For the last six years he worked as Logistics Manager for Galliford Try International, a UK-based construction company who have built a new £50m research station for the British Antarctic Survey at Halley. He has also worked as an expedition leader for Tangent Expeditions – a company that specialises in mountaineering, skiing and man-hauling trips to Greenland – including a successful east-west unsupported ski/kite icecap crossing. He was the polar guide for the Circle 66 Expedition (2008) – an attempt by an international group of breast cancer survivors to cross the Greenland icecap using dog teams. Brian has wide mountaineering and skiing experience around the world, including first ascents in Andes and Greenland. He has also covered many thousands of miles of ocean sailing with voyages to high latitudes in Alaska, Labrador and Greenland where he has combined sailing with mountaineering. He was awarded the Polar Medal in 1992. Ian Prickett, Engineer: Ian is a 34-year-old engineer from Gosport, Hampshire. -

Fiennes Antarctic Winter Crossing Bid a Trip Into 'Unknown' 6 January 2013

Fiennes Antarctic winter crossing bid a trip into 'unknown' 6 January 2013 summer," Fiennes, 68, told AFP. "So we aren't any more expert than anybody else at winter travel. There is no past history of winter travel in Antarctica apart from the 60 mile journey. So we are into the unknown." The Antarctic has the earth's lowest recorded temperature of nearly minus 90 degrees Celsius (-130 degree Fahrenheit) and levels of around minus 70 are expected during the six-month crossing which will be mostly in darkness. The expedition will sail from Cape Town on Monday and dock in the Antarctic later this month where a Explorers Sir Ranulph Fiennes (L) and Anton Bowring six-member team will prepare to leave in March talk to journalists on January 6, 2013 in Cape Town. with no option of rescue once on the ice unlike in Fiennes is leading a team of explorers willing to succeed other expeditions. in the last great polar challenge: crossing Antarctica during the winter. "This is the first time once we've gone out, all the aeroplanes, all the ships from Antarctica disappear for eight months and we're on our own and then you're in a situation where you would die," said Adventurer Sir Ranulph Fiennes on Sunday said Fiennes. his bid for the world's first Antarctic winter crossing, with no option of rescue, was a trip into the "That is why we have to try and take with us a unknown despite his multiple record expeditions. whole year of supplies and a doctor and everything else like that, which makes it the biggest, heaviest Known as the world's greatest living explorer, expedition that we've ever been involved with rather Fiennes will depart Monday for the coldest place than just man against the element." on earth after crossing the Antarctic unsupported, both polar ice caps and is the oldest person to The group will be led by two skiers carrying have climbed Mount Everest.