The Origin and Rise of Market Harborough by W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Network Rail MHLSI Works.Pub

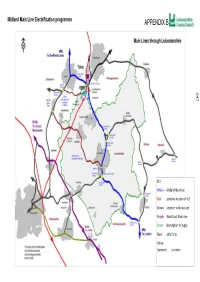

Midland Main Line Electrification programme 247 KEY MMLe — Midland Main Line Red potenal locaon of Hs2 Brown Leicester to Burton Line Purple West Coast Main Line Green Birmingham to ugby Black other lines Yellow diamonds %uncons POST HENDY REVIEW—UPDATE The Hendy Enhancements delivery plan update (Jan 2016) Electrification of the Midland Main Line has resumed under plans announced as part of Sir Peter Hendy’s work to reset Network Rail’s upgrade programme. Work on electrifying the Midland Main Line, the vital long-distance corridor that serves the UK’s industrial heartland, will continue alongside the line-speed and capacity improvement works that were already in hand. Electrification of the line north of Bedford to Kettering and Corby is scheduled to be completed by 2019, and the line north of Kettering to Leicester, Derby/Nottingham and Sheffield by 2023. Outputs The Midland Main line Electrification Programme known as the MMLe is split into two key output dates, the first running from 2014-2019 (known as CP5) and the second, 2019-2023 (CP6). There are a number of sub projects running under the main MMLe programme which are delivering various improvements in the Leicestershire area. Each sub project has dependencies with each other to enable the full ES001- Midland Main Line electrification programme to be achieved A number of interfaces and assumptions link to these programmes and their sub projects will affect Leicestershire. ES001A- Leicester Capacity The proposed 4 tracking between Syston and Wigston is located under sub project ES001A - Leicester Capacity which can be found on page 27 of Network Rails enhancements delivery plan . -

Leicester and Leicestershire City Deal

Leicester and Leicestershire City Deal Page | 1 Executive Summary Leicester and Leicestershire is a diverse and dynamic local economy and its success is integral to driving economic growth in the United Kingdom. The area is home to just under 1 million residents and over 32,000 businesses, many in the manufacturing and logistics sectors. Leicester and Leicestershire also benefits from its location at the heart of the UK road network and close proximity to both the second largest freight handling airport in the UK and London. The area provides employment for 435,000 people and generates an estimated gross value added of £19.4 billion. Despite these strengths Leicester and Leicestershire faces a series of challenges: more than 25,000 jobs were lost between 2008 and 2011 (nearly twice the national average); youth unemployment is relatively high within the city of Leicester and parts of the county; and whilst 70% of small and medium enterprises have plans for growth many find accessing the right type of business support is complex. Some local businesses also note difficulties in filling vacancies. As part of the area’s wider Growth Strategy the City Deal seeks to tackle these key barriers. Over its lifetime the Leicester and Leicestershire Enterprise Partnership expects that the City Deal will deliver: A new employment scheme targeted at 16-24 year olds that will reduce youth unemployment by 50% by 2018, deliver 3,000 new apprenticeships and 1,000 traineeships and work placements. An innovative new employment and training scheme for young offenders. Improved co-ordination of business support services and a range of innovative business support programmes. -

Town Centre and Retail Study

Leicester City Council and Blaby District Council Town Centre and Retail Study Final Report September 2015 Address: Quay West at MediaCityUK, Trafford Wharf Road, Trafford Park, Manchester, M17 1HH Tel: 0161 872 3223 E-Mail: [email protected] Web: www.wyg.com Document Control Project: Town Centre and Retail Study Client: Leicester City Council and Blaby District Council Job Number: A088154 T:\Job Files - Manchester\A088154 - Leicester Retail Study\Reports\Final\Leicester and Blaby Retail File Origin: Study_Final Report.doc WYG Planning and Environment creative minds safe hands Contents Page 1.0 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 Current and Emerging Retail Trends ................................................................................................ 3 3.0 Planning Policy Context .................................................................................................................. 16 4.0 Original Market Research ................................................................................................................ 28 5.0 Health Check Assessments.............................................................................................................. 67 6.0 Population and Expenditure ............................................................................................................ 149 7.0 Retail Capacity in Leicester and Blaby Authority Areas ..................................................................... -

52 Fleckney Road, Kibworth Beauchamp LE8 0HE £196,000 Refurbished 3 Bedroom Home with No Upward Chain

52 Fleckney Road, Kibworth Beauchamp LE8 0HE £196,000 Refurbished 3 bedroom home with no upward chain. GENERAL 52 Fleckney Road is a fabulous home having been lovingly refurbished to a high standard. In addition to the refurbishment, the property boasts the rare benefit of off-road parking and a south facing rear garden. To the ground floor are two spacious reception rooms, a well equipped re-fitted kitchen and re-fitted bathroom. The first floor landing provides access to three generous bedrooms. Outside there are gardens to the front and rear as well as off road parking for one vehicle. LOCATION The property is located in the highly regarded village of Kibworth Beauchamp. There is an excellent range of facilities including two health centres, dentist, churches, public transport, shops, restaurants, sports clubs (tennis, football, cricket, golf and bowls), a Nursery, Pre-Schools, a Primary School and High School. The village is also within easy reach of some of South Leicestershire's most attractive countryside. There are more comprehensive amenities in Market Harborough to the South and Leicester to the North and mainline train services are available from both of these locations. The journey time from Market Harborough station to London St Pancras International is approximately one hour on the fast services. SITTING ROOM 3.71m X 3.43m min 4.09m max into bay (12'2" X 11'3" min 13'5" max into bay) Door and Bay Window to front open fire facility with tiled surround and hearth. Meter/storage cupboard, t.v point, coving, radiator, new carpet and door to DINING ROOM 3.71m x 3.71m (12'2" x 12'2") Window, electric fire, coving, t.v ariel point, new carpets and door to INNER HALL Stairs rising to the first floor, under stair storage cupboard with window, radiator, tiled flooring and door leading through to KITCHEN 3.05m x 2.13m (10' x 7') Window, wall and base mounted units, one and a half bowl sink and drainer, gas hob and electric double oven with part tiled walls and tiled flooring. -

Covid-19-Weekly-Hotspot-Report-For

Weekly COVID-19 Surveillance Report in Leicestershire Cumulative data from 01/03/2020 - 29/09/2021 This report summarises the information from the surveillance system which is used to monitor the cases of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Leicestershire. The report is based on daily data up to 29th September 2021. The maps presented in the report examine counts and rates of COVID-19 at Middle Super Output Area. Middle Layer Super Output Areas (MSOAs) are a census based geography used in the reporting of small area statistics in England and Wales. The minimum population is 5,000 and the average is 7,200. Disclosure control rules have been applied to all figures not currently in the public domain. Counts between 1 to 5 have been suppressed at MSOA level. An additional dashboard examining weekly counts of COVID-19 cases by Middle Super Output Area in Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland can be accessed via the following link: https://public.tableau.com/profile/r.i.team.leicestershire.county.council#!/vizhome/COVID-19PHEWeeklyCases/WeeklyCOVID- 19byMSOA Data has been sourced from Public Health England. The report has been complied by Business Intelligence Service in Leicestershire County Council. Weekly COVID-19 Surveillance Report in Leicestershire Cumulative data from 01/03/2020 - 29/09/2021 Breakdown of testing by Pillars of the UK Government’s COVID-19 testing programme: Pillar 1 + 2 Pillar 1 Pillar 2 combined data from both Pillar 1 and Pillar 2 data from swab testing in PHE labs and NHS data from swab testing for the -

Location and History Setting

LOCATION AND HISTORY Great Bowden lies midway between Leicester and Northampton on the Leicestershire side of the county boundary, surrounded by the rich pastureland of the Welland Valley and located in hunting country. Although almost contiguous to the town of Market Harborough, Great Bowden retains its individuality and village character. The two settlements were formally separated in 1995 when Great Bowden was granted parish status. The village comprises approximately 449 houses and had a population of 1017 according to the 2011 census Aerial Photograph of Great Bowden and the surrounding hills Great Bowden, mentioned in the Domesday Book (1086), was once the centre of a Saxon royal estate. By royal charter (1203) its neighbour, Market Harborough, was established as a trading centre, which became the commercial staging post in the district. Although Market Harborough now dominates the area, Great Bowden still maintains its separate identity, with Agriculture continuing to be the main local economy. Towards the end of the 19th century until the l920's Great Bowden was well known for its horse breeding, which has since been replaced by its hunting interests,being the base for the Fernie Hunt. The construction of the Grand Union Canal in 1809 provided a fuel supply and transport system for the local brickyard, whose products are still in evidence in the village. The canal's brief period of importance was challenged by the construction of the local railway in 1850, which split the village in half, compromising its historic integrity. In recognition of its special character a large part of the settlement has been designated a Conservation Area, which includes most of the older buildings within the village. -

Central Midlands: Leicestershire, Lincolnshire and Northamptonshire Screening and Immunisation Team), May 2017

NHS England Midlands and East (Central Midlands: Leicestershire, Lincolnshire and Northamptonshire Screening and Immunisation Team), May 2017 PGD validity There has been some confusion regarding the switch from local PGD production to the adoption of PHE national template PGDs. We have had reports of practices using national template PGDs which have been download directly from the PHE webpages, and an email sent out to warn against using an un-adopted document has unfortunately led some staff to believe that the recently supplied antenatal pertussis PGD isn’t valid. We’re sorry that this has proved confusing, but all of our communications, the information on the page above, and now on our own webpages https://www.england.nhs.uk/mids- east/our-work/ll-immunisation/, as well as in the documents themselves (template and adopted version) include wording that distinguishes between the two and spells out the legal position. Hopefully the following information will provide the necessary clarification: National templates are just that – templates. They are not PGDs, and cannot be used unless they have been authorised and adopted for use by an organisation legally permitted to do this. They are Word documents into which local text can be added to allow local authorisation to take place. Without this authorisation a non-prescribing registered health care professional would effectively be prescribing and therefore acting illegally should they administer a vaccination using the template. NHS England is able to adopt PGDs for local use. The PGD must clearly state: o the name of the authorising organisation o on whose behalf it has been authorised (i.e. -

Oadby and Wigston Borough Information Sheet

Oadby and Wigston Borough Information Sheet Local Council Information and Support Oadby & Wigston Borough Council 40 Bell Street, Wigston, Leicestershire LE18 1ED 0116 2888961 [email protected] Hours: Friday 8:45am–4:15pm Saturday Closed Sunday Closed Monday 8:45am–4:45pm Tuesday 8:45am–4:45pm Wednesday 9:30am–4:45pm Thursday 8:45am–4:45pm Supermarkets and Food Deliveries ASDA – Leicester Road, Oadby Frith, Leicester, LE2 4AH Phone: 0116 2718341 Opening Hours: Mon to Sat 8am - 10pm. Sun 10am – 4pm Sainsbury’s – Leicester Road, Wigston, Leicester, LE18 1JX Phone: 0116 2885571 Opening Hours: Mon to Sun 7am – 9pm Londis – 182 Oadby Road, Wigston, LE18 3PW Phone: 0116 2571391 Foodbanks Food banks are designed to provide short-term, emergency support with food during a crisis. Their aim is to relieve the immediate pressure of the crisis by providing food, while also providing additional support to help people resolve the crises that they face The Kings Centre, http://leicestersouth.foodbank.org. uk/ Mon 56 Bull Head Street, 18:00 - 19:00 Wigston, Tue Leicester, Closed LE18 1PA Wed 07912 194783 http://leicestersouth.foodbank.org.uk/ Mon 18:00 - 19:00 Tue Closed Wed Closed Thu 13:00 - 14:00 Fri Closed Sat Closed Sun Closed When you contact a foodbank direct, inform them you are a PA Housing resident. We have agreements with many foodbanks and it may assist them in deciding whether they can help you. The Trussell Trust covers approximately 75% of the Foodbanks across the UK. If the local numbers can’t provide the help and support you need, try the Trust at https://www.trusselltrust.org/coronavirus-food-banks/ or on 01722 580180. -

Kibworth Gas Light & Coke Company 1862-1906, 1912-1948

Kibworth Gas Light & Coke Company 1862-1906, 1912-1948 Researched and written by David A Holmes Introduction William Murdoch, a Scots engineer who worked for the firm of Boulton & Watt, is credited with the first practical use of producing gas light from coal. By the early 1790s, he had developed a system that lit his house in Redruth. By 1802, Boulton & Watt’s Soho Foundry in Birmingham was also lit by gas. The first public gas company started in 1813 when Westminster Bridge was lit by The Gas Light & Coke Company. Gas made from coal was significantly different to natural gas. 1 Manufacture of gas was introduced to Leicestershire in 1821 when the Leicester Gas Light & Coke Company opened for business. The Market Harborough Gas Light & Coke Co. opened in 1833. Supply of gas to towns and villages in the county took place slowly, and only when a sufficient body of local support ensured the investment required would produce a profit for shareholders. Information for this article on Kibworth has mainly been taken from notes made by Mr Bert Aggas for the first period and company records held at the Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland (ROLLR) for the later period. Neither the National Archives nor Companies House were able to find any information in its records though a reference No. BT31/643/2699 has been quoted. In 1943, Peter Mason, manager of the gas works, was authorised by the directors to dispose of all old papers and accounts. Origins in Kibworth Mr Bramley, Director of the Leicester firm of contractors, Messrs Bramley & Woodcock, that built the works, said he had held his first discussions about establishing a gas supply in Kibworth some three years before the Kibworth Gas Light & Coke Company opened in 1862 on New Road, next to the railway bridge. -

Accounts of the Constables of Bristol Castle

BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY'S PUBLICATIONS General Editor: PROFESSOR PATRICK MCGRATH, M.A., Assistant General Editor: MISS ELIZABETH RALPH, M .A., F.S.A. VOL. XXXIV ACCOUNTS OF THE CONSTABLES OF BRISTOL CASTLE IN 1HE THIRTEENTH AND EARLY FOURTEENTH CENTURIES ACCOUNTS OF THE CONSTABLES OF BRISTOL CASTLE IN THE THIR1EENTH AND EARLY FOUR1EENTH CENTURIES EDITED BY MARGARET SHARP Printed for the BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY 1982 ISSN 0305-8730 © Margaret Sharp Produced for the Society by A1an Sutton Publishing Limited, Gloucester Printed in Great Britain by Redwood Burn Limited Trowbridge CONTENTS Page Abbreviations VI Preface XI Introduction Xlll Pandulf- 1221-24 1 Ralph de Wiliton - 1224-25 5 Burgesses of Bristol - 1224-25 8 Peter de la Mare - 1282-84 10 Peter de la Mare - 1289-91 22 Nicholas Fermbaud - 1294-96 28 Nicholas Fermbaud- 1300-1303 47 Appendix 1 - Lists of Lords of Castle 69 Appendix 2 - Lists of Constables 77 Appendix 3 - Dating 94 Bibliography 97 Index 111 ABBREVIATIONS Abbrev. Plac. Placitorum in domo Capitulari Westmon asteriensi asservatorum abbrevatio ... Ed. W. Dlingworth. Rec. Comm. London, 1811. Ann. Mon. Annales monastici Ed. H.R. Luard. 5v. (R S xxxvi) London, 1864-69. BBC British Borough Charters, 1216-1307. Ed. A. Ballard and J. Tait. 3v. Cambridge 1913-43. BOAS Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society Transactions (Author's name and the volume number quoted. Full details in bibliography). BIHR Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research. BM British Museum - Now British Library. Book of Fees Liber Feodorum: the Book of Fees com monly called Testa de Nevill 3v. HMSO 1920-31. Book of Seals Sir Christopher Hatton's Book of Seals Ed. -

King John's Tax Innovation -- Extortion, Resistance, and the Establishment of the Principle of Taxation by Consent Jane Frecknall Hughes

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by eGrove (Univ. of Mississippi) Accounting Historians Journal Volume 34 Article 4 Issue 2 December 2007 2007 King John's tax innovation -- Extortion, resistance, and the establishment of the principle of taxation by consent Jane Frecknall Hughes Lynne Oats Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aah_journal Part of the Accounting Commons, and the Taxation Commons Recommended Citation Hughes, Jane Frecknall and Oats, Lynne (2007) "King John's tax innovation -- Extortion, resistance, and the establishment of the principle of taxation by consent," Accounting Historians Journal: Vol. 34 : Iss. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aah_journal/vol34/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Archival Digital Accounting Collection at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Accounting Historians Journal by an authorized editor of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hughes and Oats: King John's tax innovation -- Extortion, resistance, and the establishment of the principle of taxation by consent Accounting Historians Journal Vol. 34 No. 2 December 2007 pp. 75-107 Jane Frecknall Hughes SHEFFIELD UNIVERSITY MANAGEMENT SCHOOL and Lynne Oats UNIVERSITY OF WARWICK KING JOHN’S TAX INNOVATIONS – EXTORTION, RESISTANCE, AND THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE PRINCIPLE OF TAXATION BY CONSENT Abstract: The purpose of this paper is to present a re-evaluation of the reign of England’s King John (1199–1216) from a fiscal perspective. The paper seeks to explain John’s innovations in terms of widening the scope and severity of tax assessment and revenue collection. -

British Family Names

cs 25o/ £22, Cornrll IBniwwitg |fta*g BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME FROM THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF Hcnrti W~ Sage 1891 A.+.xas.Q7- B^llll^_ DATE DUE ,•-? AUG 1 5 1944 !Hak 1 3 1^46 Dec? '47T Jan 5' 48 ft e Univeral, CS2501 .B23 " v Llb«"y Brit mii!Sm?nS,£& ori8'" and m 3 1924 olin 029 805 771 The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924029805771 BRITISH FAMILY NAMES. : BRITISH FAMILY NAMES ftbetr ©riain ano fIDeaning, Lists of Scandinavian, Frisian, Anglo-Saxon, and Norman Names. HENRY BARBER, M.D. (Clerk), "*• AUTHOR OF : ' FURNESS AND CARTMEL NOTES,' THE CISTERCIAN ABBEY OF MAULBRONN,' ( SOME QUEER NAMES,' ' THE SHRINE OF ST. BONIFACE AT FULDA,' 'POPULAR AMUSEMENTS IN GERMANY,' ETC. ' "What's in a name ? —Romeo and yuliet. ' I believe now, there is some secret power and virtue in a name.' Burton's Anatomy ofMelancholy. LONDON ELLIOT STOCK, 62, PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C. 1894. 4136 CONTENTS. Preface - vii Books Consulted - ix Introduction i British Surnames - 3 nicknames 7 clan or tribal names 8 place-names - ii official names 12 trade names 12 christian names 1 foreign names 1 foundling names 1 Lists of Ancient Patronymics : old norse personal names 1 frisian personal and family names 3 names of persons entered in domesday book as HOLDING LANDS temp. KING ED. CONFR. 37 names of tenants in chief in domesday book 5 names of under-tenants of lands at the time of the domesday survey 56 Norman Names 66 Alphabetical List of British Surnames 78 Appendix 233 PREFACE.