Allegory in the Novels of Isaac Bashevis Singer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of American Studies, 52(3), 660-681

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Explore Bristol Research Savvas, T. (2018). The Other Religion of Isaac Bashevis Singer. Journal of American Studies, 52(3), 660-681. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021875817000445 Peer reviewed version Link to published version (if available): 10.1017/S0021875817000445 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the author accepted manuscript (AAM). The final published version (version of record) is available online via CUP at https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-american-studies/article/other-religion-of-isaac- bashevis-singer/CD2A18F086FDF63F29F0884B520BE385. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/pure/about/ebr-terms 1 The Other Religion of Isaac Bashevis Singer Theophilus Savvas, University of Bristol This essay analyzes the later fiction of Nobel Prize-winning writer Isaac Bashevis Singer through the prism of his vegetarianism. Singer figured his adoption of a vegetarian diet in 1962 as a kind of conversion, pronouncing it a “religion” that was central to his being. Here I outline Singer’s vegetarian philosophy, and argue that it was the underlying ethical precept in the fiction written after the conversion. I demonstrate the way in which that ethic informs the presentation of both Judaism and women in Singer’s later writings. -

Lesson Eight

Class of Nonviolence – Lesson Eight Animals, My Brethren by Edgar Kupfer-Koberwitz The following pages were written in the wounded or killed for my pleasure and Concentration Camp Dachau, in the midst of all convenience? kinds of cruelties. They were furtively scrawled in • Is it not only too natural that I do not a hospital barrack where I stayed during my inflict on other creatures the same thing illness, in a time when Death grasped day by day which, I hope and fear, will never be after us, when we lost twelve thousand within inflicted on me? Would it not be most four and a half months. unfair to do such things for no other purpose than for enjoying a trifling Dear Friend: physical pleasure at the expense of others' sufferings, others' deaths? You asked me why I do not eat meat and you are wondering at the reasons of my behavior. These creatures are smaller and more helpless Perhaps you think I took a vow -- some kind of than I am, but can you imagine a reasonable man penitence -- denying me all the glorious of noble feelings who would like to base on such pleasures of eating meat. You remember juicy a difference a claim or right to abuse the steaks, succulent fishes, wonderfully tasted weakness and the smallness of others? Don't you sauces, deliciously smoked ham and thousand think that it is just the bigger, the stronger, the wonders prepared out of meat, charming superior's duty to protect the weaker creatures thousands of human palates; certainly you will instead of persecuting them, instead of killing remember the delicacy of roasted chicken. -

THE MAGICIAN of LUBLIN by Isaac Bashevis Singer

THE MAGICIAN OF LUBLIN by Isaac Bashevis Singer AUTHOR’S BIO Isaac Bashevis Singer immigrated to the United States in 1935, which was the year of his first novel Satan in Goray. Since then, he wrote in Yiddish more or less exclusively about the Jewish world of pre-war Poland, or more exactly, about the Hasidic world of pre-war Poland, into which he was born, the son of a rabbi, in 1904. Singer published his autobiography in four volumes: In My Father’s Court (1966), A Little Boy in Search of God (1976), A Young Man in Search of Love (1978), and Lost in America (1981). His best-known novels include The Magician of Lublin (1960), The Slave (1962), Enemies, a Love Story (1972), and Shosha (1978). In 1978, Singer received the Nobel Prize in Literature. The citation praised him for his art in narrative and noted that although the background of his works was the Polish-Jewish tradition, they revealed the human condition, which transcends cultural barriers. In his acceptance speech, Singer commented on the values that he had learned from the humble people whom he had known in childhood, who spoke in a vanishing tongue, the language of a people in exile. After a series of strokes, Singer died in Surfside, Florida, on July 24, 1991. ABOUT THE BOOK The Magician of Lublin Written in 1958, serialized in 1959, and published in English in 1960, The Magician of Lublin also deals with human passions, but it is not overcast with the gloom of past events. It reflects an expansiveness often missing in Singer’s works. -

Throughout His Writing Career, Nelson Algren Was Fascinated by Criminality

RAGGED FIGURES: THE LUMPENPROLETARIAT IN NELSON ALGREN AND RALPH ELLISON by Nathaniel F. Mills A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor Alan M. Wald, Chair Professor Marjorie Levinson Professor Patricia Smith Yaeger Associate Professor Megan L. Sweeney For graduate students on the left ii Acknowledgements Indebtedness is the overriding condition of scholarly production and my case is no exception. I‘d like to thank first John Callahan, Donn Zaretsky, and The Ralph and Fanny Ellison Charitable Trust for permission to quote from Ralph Ellison‘s archival material, and Donadio and Olson, Inc. for permission to quote from Nelson Algren‘s archive. Alan Wald‘s enthusiasm for the study of the American left made this project possible, and I have been guided at all turns by his knowledge of this area and his unlimited support for scholars trying, in their writing and in their professional lives, to negotiate scholarship with political commitment. Since my first semester in the Ph.D. program at Michigan, Marjorie Levinson has shaped my thinking about critical theory, Marxism, literature, and the basic protocols of literary criticism while providing me with the conceptual resources to develop my own academic identity. To Patricia Yaeger I owe above all the lesson that one can (and should) be conceptually rigorous without being opaque, and that the construction of one‘s sentences can complement the content of those sentences in productive ways. I see her own characteristic synthesis of stylistic and conceptual fluidity as a benchmark of criticism and theory and as inspiring example of conceptual creativity. -

The Proliferation of the Grotesque in Four Novels of Nelson Algren

THE PROLIFERATION OF THE GROTESQUE IN FOUR NOVELS OF NELSON ALGREN by Barry Hamilton Maxwell B.A., University of Toronto, 1976 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department ot English ~- I - Barry Hamilton Maxwell 1986 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY August 1986 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL NAME : Barry Hamilton Maxwell DEGREE: M.A. English TITLE OF THESIS: The Pro1 iferation of the Grotesque in Four Novels of Nel son A1 gren Examining Committee: Chai rman: Dr. Chin Banerjee Dr. Jerry Zaslove Senior Supervisor - Dr. Evan Alderson External Examiner Associate Professor, Centre for the Arts Date Approved: August 6, 1986 I l~cr'ct~ygr.<~nl lu Sinnri TI-~J.;~;University tile right to lend my t Ire., i6,, pr oJcc t .or ~~ti!r\Jc~tlcr,!;;ry (Ilw tit lc! of which is shown below) to uwr '. 01 thc Simon Frasor Univer-tiity Libr-ary, and to make partial or singlc copic:; orrly for such users or. in rcsponse to a reqclest from the , l i brtlry of rllly other i111i vitl.5 i ty, Or c:! her- educational i r\.;t i tu't ion, on its own t~l1.31f or for- ono of i.ts uwr s. I furthor agroe that permissior~ for niir l tipl c copy i rig of ,111i r; wl~r'k for .;c:tr~l;rr.l y purpose; may be grdnted hy ri,cs oi tiI of i Ittuli I t ir; ~lntlc:r-(;io~dtt\at' copy in<) 01. -

And Other Stories. Isaac Bashevis Singer

Old Love: And Other Stories. Isaac Bashevis Singer 2001. 0099286467, 9780099286462. Old Love: And Other Stories. Isaac Bashevis Singer. Vintage, 2001. This classic collection explores the varieties of wisdom gained with age and especially those that teach us how to love, as "in love the young are just beginners and the art of loving matures with age and experience". Tales of curious marriages and divorce mingle with psychic experiences and curses, acts of bravery and loneliness, love and hatred. file download cebuxe.pdf Aug 1, 1979. 320 pages. Isaac Bashevis Singer. ISBN:0374515387. This book of twenty stories is Isaac Bashevis Singer's fifth collection and contains such classics as "The Cafeteria" and "On the Way to the Poorhouse.". Fiction. A Friend of Kafka Old Love: And Other Stories pdf download ISBN:0140048073. The magician of Lublin. 1980. Fiction. 200 pages. Isaac Bashevis Singer Love: pdf download The Manor. ISBN:0299205444. Fiction. 1979. Isaac Bashevis Singer. The Manor and The Estatecombined in this one-volume editionbold tales of Polish Jews in the latter half of the nineteenth century, a time of rapid industrial growth and. 818 pages. & the Estate Short Friday. And Other Stories. 256 pages. Isaac Bashevis Singer. Fiction. ISBN:0374504407. 1964 Fiction. ISBN:9780374531539. The Penitent. 176 pages. Isaac Bashevis Singer. Nov 26, 2007. Joseph Shapiro, a New York businessman, experiences a mid-life crisis. He leaves his wife, his mistress, his business and goes to Israel in search of religious Orthodoxy pdf file May 16, 2003. ISBN:0374529116. Passions. 324 pages. Fiction. Isaac Bashevis Singer download ISBN:0374506809. -

The Grotesque in the Fiction of Joyce Carol Oates

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1979 The Grotesque in the Fiction of Joyce Carol Oates Kathleen Burke Bloom Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Bloom, Kathleen Burke, "The Grotesque in the Fiction of Joyce Carol Oates" (1979). Master's Theses. 3012. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/3012 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1979 Kathleen Burke Bloom THE GROTESQUE IN THE FICTION OF JOYCE CAROL OATES by Kathleen Burke Bloom A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 1979 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Professors Thomas R. Gorman, James E. Rocks, and the late Stanley Clayes for their encouragement and advice. Special thanks go to Professor Bernard P. McElroy for so generously sharing his views on the grotesque, yet remaining open to my own. Without the safe harbors provided by my family, Professor Jean Hitzeman, O.P., and Father John F. Fahey, M.A., S.T.D., this voyage into the contemporary American nightmare would not have been possible. -

Ernest Hemingway Global American Modernist

Ernest Hemingway Global American Modernist Lisa Tyler Sinclair Community College, USA Iconic American modernist Ernest Hemingway spent his entire adult life in an interna- tional (although primarily English-speaking) modernist milieu interested in breaking with the traditions of the past and creating new art forms. Throughout his lifetime he traveled extensively, especially in France, Spain, Italy, Cuba, and what was then British East Africa (now Kenya and Tanzania), and wrote about all of these places: “For we have been there in the books and out of the books – and where we go, if we are any good, there you can go as we have been” (Hemingway 1935, 109). At the time of his death, he was a global celebrity recognized around the world. His writings were widely translated during his lifetime and are still taught in secondary schools and universities all over the globe. Ernest Hemingway was born 21 July 1899, in Oak Park, Illinois, also the home of Frank Lloyd Wright, one of the most famous modernist architects in the world. Hemingway could look across the street from his childhood home and see one of Wright’s innovative designs (Hays 2014, 54). As he was growing up, Hemingway and his family often traveled to nearby Chicago to visit the Field Museum of Natural History and the Chicago Opera House. Because of the 1871 fire that destroyed structures over more than three square miles of the city, a substantial part of Chicago had become a clean slate on which late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century architects could design what a modern city should look like. -

Autobiography As Fiction, Fiction As Autobiography: a Study of Autobiographical Impulse in Pak Wans Ŏ’S the Naked Tree and Who Ate up All the Shinga

Autobiography as Fiction, Fiction as Autobiography: A Study of Autobiographical Impulse in Pak Wans ŏ’s The Naked Tree and Who Ate Up All the Shinga By Sarah Suh A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto © Copyright by Sarah Suh (2014) Autobiography as Fiction, Fiction as Autobiography: A Study of Autobiographical Impulse in Pak Wans ŏ’s The Naked Tree and Who Ate Up All the Shinga Sarah Suh Master of Arts Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto 2014 Abstract Autobiographical studies in the past few decades have made it increasingly clear that it is no longer possible to leave autobiography to its conventional understanding as a nonfiction literary genre. The uneasy presence of fiction in autobiography and autobiography in fiction has gained autobiography a reputation for elusiveness as a literary genre that defies genre distinction. This thesis examines the literary works of South Korean writer Pak Wans ŏ and the autobiographical impulse that drives Pak to write in the fictional form. Following a brief overview of autobiography and its problems as a literary genre, Pak’s reasons for writing fiction autobiographically are explained in an investigation of her first novel, The Naked Tree , and its transformation from nonfiction biography to autobiographical fiction. The next section focuses on the novel, Who Ate Up All the Shinga , examining the ways that Pak reveals her ambivalence towards maintaining boundaries of nonfiction/fiction in her writing. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my family for always being there for me. -

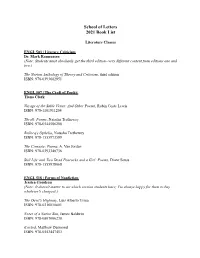

2021 Book List

School of Letters 2021 Book List Literature Classes ENGL 503 | Literary Criticism Dr. Mark Rasmussen (Note: Students must absolutely get the third edition--very different content from editions one and two.) The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, third edition ISBN: 978-0393602951 ENGL 507 | The Craft of Poetry Tiana Clark Voyage of the Sable Venus: And Other Poems, Robin Coste Lewis ISBN: 978-1101911204 Thrall: Poems, Natasha Trethewey ISBN: 978-0544586208 Bellocq's Ophelia, Natasha Trethewey ISBN: 978-1555973599 The Cineaste: Poems, A. Van Jordan ISBN: 978-0393348736 Still Life with Two Dead Peacocks and a Girl: Poems, Diane Seuss ISBN: 978-1555978068 ENGL 518 | Forms of Nonfiction Jessica Goudeau (Note: It doesn't matter to me which version students have; I'm always happy for them to buy whatever's cheapest.) The Devil's Highway, Luis Alberto Urrea ISBN: 978-0316010801 Notes of a Native Son, James Baldwin ISBN: 978-0807006238 Evicted, Matthew Desmond ISBN: 978-0553447453 Fun Home, Alison Bechdel ISBN: 978-0544709041 Rarely in the history of the United States has writing for social change felt more urgent—or been more marketable—for nonfiction writers than now. Though their approaches are very different, journalists, memoirists, essayists, and other nonfiction writers often begin their work from a moment of frustration, a sense that a story, a situation, or an idea is not right and should be changed. Once the book is released, rave reviewers of nonfiction books often praise authors’ ability to “humanize” an experience and “shine a light” on injustice, or they make bold claims about a work’s ability to “move hearts and minds” and “change the world.” But few nonfiction writers actually learn the methodology—the techniques, approaches, and principles—to move from that moment of noticing injustice to a well-written and persuasive final book that can contribute to the social good. -

Towards a Boundless Ethic

WellBeing International WBI Studies Repository 6-1993 Towards A Boundless Ethic Henry Spira Animal Rights International Follow this and additional works at: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/hscedi Part of the Animal Studies Commons, Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons, and the Nature and Society Relations Commons Recommended Citation Spira, H. (1993, June). Towards a boundless ethic. Fellowship: 30-31. This material is brought to you for free and open access by WellBeing International. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Towards A Boundless Ethic Henry Spira “In their behavior toward creatures, all men were Nazis. The smugness with which man could do with other species as pleased exemplified the most extreme racist theories, the principle that might is right.” -- Isaac Bashevis Singer Today we have particularly good reason to be concerned with the violence humans inflict on humans. But should those of us who care about the violence inflicted on men, women and children care about the violence inflicted on animals? In my own mind, the need for a consistent ethic of nonviolence for both human and non-human animals is obvious•-one is an extension of the other. When thinking of violence to animals many people may just conjure up a gun-toting trophy hunter or a sadistic psychopath torturing a dog. Yet to limit one's vision to these dramatic but occasional acts of violence is to miss the point. The real, massive violence is part of the structure of our culture-animals are considered lab tools and edibles. -

Liberté, Égalité, Animalité: Human–Animal Comparisons In

Transnational Environmental Law, Page 1 of 29 © 2016 Cambridge University Press doi:10.1017/S204710251500031X SYMPOSIUM ARTICLE Liberté, Égalité, Animalité: † Human–Animal Comparisons in Law Anne Peters* Abstract This article problematizes the discrepancy between the wealth of international law serving human needs and rights and the international regulatory deficit concerning animal welfare and animal rights. It suggests that, in the face of scientific evidence, the legal human–animal boundary (as manifest notably in the denial of rights to animals) needs to be properly justified. Unmasking the (to some extent) ‘imagined’ nature of the human–animal boundary, and shedding light on the persistence of human–animal comparisons for pernicious and beneficial purposes of the law, can offer inspirations for legal reform in the field of animal welfare and even animal rights. Keywords Animal rights, Human rights, Animal welfare, Speciesism, Discrimination, Cultural imperialism 1. introduction: civilized humans against all others Between 1879 and 1935, the Basel Zoo in Switzerland entertained the public with Völkerschauen,or‘people’s shows’, in which non-European human beings were displayed wearing traditional dress, in front of makeshift huts, performing handcrafts.1 These shows attracted more visitors at the time than the animals in the zoo. The organizers of these Völkerschauen were typically animal dealers and zoo directors, and the humans exhibited were often recruited from Sudan, a region where most of the African zoo and circus animals were also being trapped. The organizers made sure that the individuals on display did not speak any European language, so that verbal communication between them and the zoo visitors was impossible.