The Last Arab Siege of Constantinople (717–718): a Neglected Source Robert J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Empires in East Asia

DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=NL-A Module 3 Empires in East Asia Essential Question In general, was China helpful or harmful to the development of neighboring empires and kingdoms? About the Photo: Angkor Wat was built in In this module you will learn how the cultures of East Asia influenced one the 1100s in the Khmer Empire, in what is another, as belief systems and ideas spread through both peaceful and now Cambodia. This enormous temple was violent means. dedicated to the Hindu god Vishnu. Explore ONLINE! SS.912.W.2.19 Describe the impact of Japan’s physiography on its economic and political development. SS.912.W.2.20 Summarize the major cultural, economic, political, and religious developments VIDEOS, including... in medieval Japan. SS.912.W.2.21 Compare Japanese feudalism with Western European feudalism during • A Mongol Empire in China the Middle Ages. SS.912.W.2.22 Describe Japan’s cultural and economic relationship to China and Korea. • Ancient Discoveries: Chinese Warfare SS.912.G.2.1 Identify the physical characteristics and the human characteristics that define and differentiate regions. SS.912.G.4.9 Use political maps to describe the change in boundaries and governments within • Ancient China: Masters of the Wind continents over time. and Waves • Marco Polo: Journey to the East • Rise of the Samurai Class • Lost Spirits of Cambodia • How the Vietnamese Defeated the Mongols Document Based Investigations Graphic Organizers Interactive Games Image with Hotspots: A Mighty Fighting Force Image with Hotspots: Women of the Heian Court 78 Module 3 DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=NL-A Timeline of Events 600–1400 Explore ONLINE! East and Southeast Asia World 600 618 Tang Dynasty begins 289-year rule in China. -

Constantinople As Center and Crossroad

Constantinople as Center and Crossroad Edited by Olof Heilo and Ingela Nilsson SWEDISH RESEARCH INSTITUTE IN ISTANBUL TRANSACTIONS, VOL. 23 Table of Contents Acknowledgments ......................................................................... 7 OLOF HEILO & INGELA NILSSON WITH RAGNAR HEDLUND Constantinople as Crossroad: Some introductory remarks ........................................................... 9 RAGNAR HEDLUND Byzantion, Zeuxippos, and Constantinople: The emergence of an imperial city .............................................. 20 GRIGORI SIMEONOV Crossing the Straits in the Search for a Cure: Travelling to Constantinople in the Miracles of its healer saints .......................................................... 34 FEDIR ANDROSHCHUK When and How Were Byzantine Miliaresia Brought to Scandinavia? Constantinople and the dissemination of silver coinage outside the empire ............................................. 55 ANNALINDEN WELLER Mediating the Eastern Frontier: Classical models of warfare in the work of Nikephoros Ouranos ............................................ 89 CLAUDIA RAPP A Medieval Cosmopolis: Constantinople and its foreigners .............................................. 100 MABI ANGAR Disturbed Orders: Architectural representations in Saint Mary Peribleptos as seen by Ruy González de Clavijo ........................................... 116 ISABEL KIMMELFIELD Argyropolis: A diachronic approach to the study of Constantinople’s suburbs ................................... 142 6 TABLE OF CONTENTS MILOŠ -

Exiling Bishops: the Policy of Constantius II

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Classical Studies Faculty Publications Classical Studies 2014 Exiling Bishops: The olicP y of Constantius II Walter Stevenson University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/classicalstudies-faculty- publications Part of the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Stevenson, Walt. "Exiling Bishops: The oP licy of Canstantius II." Dumbarton Oaks Papers 68 (2014): 7-27. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Classical Studies at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Classical Studies Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Exiling Bishops: The Policy of Constantius II Walt Stevenson onstantius II was forced by circumstances to all instances in which Constantius II exiled bishops Cmake innovations in the policy that his father and focus on a sympathetic reading of his strategy.2 Constantine had followed in exiling bishops. While Though the sources for this period are muddled and ancient tradition has made the father into a sagacious require extensive sorting, a panoramic view of exile saint and the son into a fanatical demon, recent schol- incidents reveals a pattern in which Constantius moved arship has tended to stress continuity between the two past his father’s precedents to mold a new, intelligent regimes.1 This article will attempt to gather -

OCTOBER 2019 for His Name Alone Is Exalted! Saints Constantine and Helen Greek Orthodox Church Rev

Let them praise the Name of the LORD! OCTOBER 2019 For His Name alone is exalted! Saints Constantine and Helen Greek Orthodox Church Rev. Father John Beal Sunday Services 8:50 AM Matins – 10:00 AM Divine Liturgy 43404 30th St. W, Lancaster, California 93536 Website: www.stsch.org – Church Phone: 661-945-1212 For confirmation on any event, please phone or text Sylva Robinson at 661-794-8307 Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat 1 2 3 4 5 Great Vespers 7 PM 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 3RD Sunday of Luke Luke 7:11-16 Church School Classes Start Festival Celebration Luncheon 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Holy Fathers Great 7TH Synod Vespers Luke 8:5-15 7 PM 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 6TH Sunday of Luke Feed the Luke 8:26-39 Hungry 8:30-10:30AM Parish Council 27 28 29 30 31 TH 7 Sunday of Luke Holy Luke 8:41-56 Protection of the Theotokos CHURCH CALENDAR FOR OCTOBER 20191 Fast Wednesdays and Fridays this month. See fasting guideline below. Tue 1 Holy Protection of the Most-Holy Theotokos (Greece celebrates on Oct 28th) St. Romanos the Melodist. Apostle Ananias of the 70. St. John Cucuzelis Hieromartyr Cyprian, the former Sorcerer, and Virgin martyr Justina. St. Damaris of Athens. St. Theodore Gabra, the soldier. Thu 3 Hieromartyr Dionysios the Areopagite, 1st Bishop of Athens. Hieromartyr Hierotheos, Bishop of Athens. St. Ammon of Egypt, disciple of St. Paul. Martyr Domnina Sat 5 Martyr Charitina. Righteous Methodia of Cimolos. -

Adoption Des Déclarations Rétrospectives De Valeur Universelle Exceptionnelle

Patrimoine mondial 40 COM WHC/16/40.COM/8E.Rev Paris, 10 juin 2016 Original: anglais / français ORGANISATION DES NATIONS UNIES POUR L’ÉDUCATION, LA SCIENCE ET LA CULTURE CONVENTION CONCERNANT LA PROTECTION DU PATRIMOINE MONDIAL, CULTUREL ET NATUREL COMITE DU PATRIMOINE MONDIAL Quarantième session Istanbul, Turquie 10 – 20 juillet 2016 Point 8 de l’ordre du jour provisoire : Etablissement de la Liste du patrimoine mondial et de la Liste du patrimoine mondial en péril. 8E: Adoption des Déclarations rétrospectives de valeur universelle exceptionnelle RESUME Ce document présente un projet de décision concernant l’adoption de 62 Déclarations rétrospectives de valeur universelle exceptionnelle soumises par 18 États parties pour les biens n’ayant pas de Déclaration de valeur universelle exceptionnelle approuvée à l’époque de leur inscription sur la Liste du patrimoine mondial. L’annexe contient le texte intégral des Déclarations rétrospectives de valeur universelle exceptionnelle dans la langue dans laquelle elles ont été soumises au Secrétariat. Projet de décision : 40 COM 8E, voir Point II. Ce document annule et remplace le précédent I. HISTORIQUE 1. La Déclaration de valeur universelle exceptionnelle est un élément essentiel, requis pour l’inscription d’un bien sur la Liste du patrimoine mondial, qui a été introduit dans les Orientations devant guider la mise en oeuvre de la Convention du patrimoine mondial en 2005. Tous les biens inscrits depuis 2007 présentent une telle Déclaration. 2. En 2007, le Comité du patrimoine mondial, dans sa décision 31 COM 11D.1, a demandé que les Déclarations de valeur universelle exceptionnelle soient rétrospectivement élaborées et approuvées pour tous les biens du patrimoine mondial inscrits entre 1978 et 2006. -

Constructing the Seventh Century

COLLÈGE DE FRANCE – CNRS CENTRE DE RECHERCHE D’HISTOIRE ET CIVILISATION DE BYZANCE TRAVAUX ET MÉMOIRES 17 constructing the seventh century edited by Constantin Zuckerman Ouvrage publié avec le concours de la fondation Ebersolt du Collège de France et de l’université Paris-Sorbonne Association des Amis du Centre d’Histoire et Civilisation de Byzance 52, rue du Cardinal-Lemoine – 75005 Paris 2013 PREFACE by Constantin Zuckerman The title of this volume could be misleading. “Constructing the 7th century” by no means implies an intellectual construction. It should rather recall the image of a construction site with its scaffolding and piles of bricks, and with its plentiful uncovered pits. As on the building site of a medieval cathedral, every worker lays his pavement or polishes up his column knowing that one day a majestic edifice will rise and that it will be as accomplished and solid as is the least element of its structure. The reader can imagine the edifice as he reads through the articles collected under this cover, but in this age when syntheses abound it was not the editor’s aim to develop another one. The contributions to the volume are regrouped in five sections, some more united than the others. The first section is the most tightly knit presenting the results of a collaborative project coordinated by Vincent Déroche. It explores the different versions of a “many shaped” polemical treatise (Dialogica polymorpha antiiudaica) preserved—and edited here—in Greek and Slavonic. Anti-Jewish polemics flourished in the seventh century for a reason. In the centuries-long debate opposing the “New” and the “Old” Israel, the latter’s rejection by God was grounded in an irrefutable empirical proof: God had expelled the “Old” Israel from its promised land and given it to the “New.” In the first half of the seventh century, however, this reasoning was shattered, first by the Persian conquest of the Holy Land, which could be viewed as a passing trial, and then by the Arab conquest, which appeared to last. -

How Could Phenological Records from the Chinese Poems of the Tang and Song Dynasties

https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-2020-122 Preprint. Discussion started: 28 September 2020 c Author(s) 2020. CC BY 4.0 License. How could phenological records from the Chinese poems of the Tang and Song Dynasties (618-1260 AD) be reliable evidence of past climate changes? Yachen Liu1, Xiuqi Fang2, Junhu Dai3, Huanjiong Wang3, Zexing Tao3 5 1School of Biological and Environmental Engineering, Xi’an University, Xi’an, 710065, China 2Faculty of Geographical Science, Key Laboratory of Environment Change and Natural Disaster MOE, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, 100875, China 3Key Laboratory of Land Surface Pattern and Simulation, Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Science (CAS), Beijing, 100101, China 10 Correspondence to: Zexing Tao ([email protected]) Abstract. Phenological records in historical documents have been proved to be of unique value for reconstructing past climate changes. As a literary genre, poetry reached its peak period in the Tang and Song Dynasties (618-1260 AD) in China, which could provide abundant phenological records in this period when lacking phenological observations. However, the reliability of phenological records from 15 poems as well as their processing methods remains to be comprehensively summarized and discussed. In this paper, after introducing the certainties and uncertainties of phenological information in poems, the key processing steps and methods for deriving phenological records from poems and using them in past climate change studies were discussed: -

MEDIEVAL DAMASCUS Arabic Book Culture, Library Culture and Reading Culture Is Significantly Enriched.’ Li Guo, University of Notre Dame and MEDIEVAL

PLURALITY KONRAD HIRSCHLER ‘This is a tour de force of ferocious codex dissection, relentless bibliographical probing and imaginative reconstructive storytelling. Our knowledge of medieval MEDIEVAL DAMASCUS DAMASCUS MEDIEVAL Arabic book culture, library culture and reading culture is significantly enriched.’ Li Guo, University of Notre Dame AND MEDIEVAL The first documented insight into the content and DIVERSITY structure of a large-scale medieval Arabic library The written text was a pervasive feature of cultural practices in the medieval Middle East. At the heart of book circulation stood libraries that experienced a rapid expansion from the DAMASCUS twelfth century onwards. While the existence of these libraries is well known, our knowledge of their content and structure has been very limited as hardly any medieval Arabic catalogues have been preserved. This book discusses the largest and earliest medieval library of the PLURALITY AND Middle East for which we have documentation – the Ashrafiya library in the very centre of IN AN Damascus – and edits its catalogue. The catalogue shows that even book collections attached to Sunni religious institutions could hold very diverse titles, including Muʿtazilite theology, DIVERSITY IN AN Shiʿite prayers, medical handbooks, manuals for traders, stories from the 1001 Nights and texts extolling wine consumption. ARABIC LIBRARY ARABIC LIBRARY Listing over two thousand books the Ashrafiya catalogue is essential reading for anybody interested in the cultural and intellectual history of Arabic societies. -

How Ecumenical Was Early Islam?

Near Eastern Languages and Civilization The Farhat J. Ziadeh Distinguished Lecture in Arab and Islamic Studies How Ecumenical Was Early Islam? Professor Fred M. Donner University of Chicago Dear Friends and Colleagues, It is my distinct privilege to provide you with a copy of the eleventh Far- hat J. Ziadeh Distinguished Lecture in Arab and Islamic Studies, “How Ecumenical Was Early Islam?” delivered by Fred M. Donner on April 29, 2013. The Ziadeh Fund was formally endowed in 2001. Since that time, with your support, it has allowed us to strengthen our educational reach and showcase the most outstanding scholarship in Arab and Islamic Studies, and to do so always in honor of our dear colleague Farhat Ziadeh, whose contributions to the fields of Islamic law, Arabic language, and Islamic Studies are truly unparalleled. Farhat J. Ziadeh was born in Ramallah, Palestine, in 1917. He received his B.A. from the American University of Beirut in 1937 and his LL.B. from the University of London in 1940. He then attended Lincoln’s Inn, London, where he became a Barrister-at-Law in 1946. In the final years of the British Mandate, he served as a Magistrate for the Government of Palestine before eventually moving with his family to the United States. He was appointed Professor of Arabic and Islamic Law at Princeton University, where he taught until 1966, at which time he moved to the University of Washington. The annual lectureship in his name is a fitting tribute to his international reputation and his national service to the discipline of Arabic and Islam- ic Studies. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Methodios I patriarch of Constantinople: churchman, politician and confessor for the faith Bithos, George P. How to cite: Bithos, George P. (2001) Methodios I patriarch of Constantinople: churchman, politician and confessor for the faith, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4239/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 METHODIOS I PATRIARCH OF CONSTANTINOPLE Churchman, Politician and Confessor for the Faith Submitted by George P. Bithos BS DDS University of Durham Department of Theology A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Orthodox Theology and Byzantine History 2001 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published in any form, including' Electronic and the Internet, without the author's prior written consent All information derived from this thesis must be acknowledged appropriately. -

CP Thin Wall Conduit Fittings (For EMT Conduit)

2: 5: 50: 95: 98: 100: SYS19: BASE2 JOB: CRMAIN06-0273-8 Name: CP-273 DATE: JAN 19 2006 Time: 5:14:19 PM Operator: JB COLOR: CMYK TCP: 15001 Typedriver Name: TS name csm no.: 100 Zoom: 100 Thin Wall Conduit Fittings ɀ Set Screw Type Fittings CP ɀ Compression Type Fittings (For EMT Conduit) ɀ Combination Couplings COMPRESSION TYPE FITTINGS – STEEL ɀ SET SCREW TYPE FITTINGS Couplings CP UL File No. E-22132 Weight Features: Set Screw Type Unit Standard Lbs. Per ɀ Pre-set & Staked Robertson Head Screws Fittings Thinwall Cat. # Size Quantity Package 100 ɀ Male Hub Threads - NPSM ɀ Steel Locknuts 660S 1⁄2⍯ 50 250 12 ɀ Heavy Steel Walls 661S 3⁄4⍯ 25 125 18 ɀ 662 1⍯ 25 100 27 Standard Material: Steel ɀ Standard Finish: Zinc Plated 1 ⍯ 663 1 ⁄4 10 50 46 Concrete Tight 1 ⍯ 664 1 ⁄2 10 50 63 Straight Connectors – Insulated 665 2⍯ 52592UL File No. E-22132 666 21⁄2⍯ 2 10 250 Weight 667 3⍯ 1 5 410 Unit Standard Lbs. Per 668 31⁄2⍯ 1 5 390 Cat. # Size Quantity Package 100 669 4⍯ 1 5 485 1450 1⁄2⍯ 50 250 9 1451 3⁄4⍯ 25 100 14 SET SCREW TYPE FITTINGS 1452 1⍯ 20 100 23 New Space-Saver EMT Connector - Set Screw 1453* 11⁄4⍯ 10 50 46 UL File No. E-22132 1454* 11⁄2⍯ 10 50 50 Features: 1455* 2⍯ 52578 ɀ Used to join EMT conduit to a box or 1456*+ 21⁄2⍯ 2 10 130 enclosure 1457*+ 3⍯ 1 5 140 ɀ Designed with the male threads on the 1458*+ 31⁄2⍯ 1 5 180 locknut, the Space-Saver takes up virtually no 1459*+ 4⍯ 1 5 225 room inside the box, and the smooth pulling surface eliminates the * Two Tightening Screws need for a bushing or insulated throat Straight Connectors – Non-Insulated ɀ Angled teeth on locknut bite into enclosure, preventing loosening UL File No. -

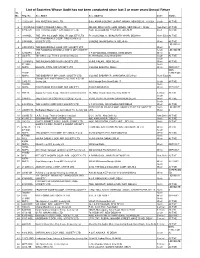

List of Societies Not Audited for Last 3 Years Or More/Annual Return

List of Societies Whose Audit has not been conducted since last 3 or more years/Annual Return Sr. No. Reg. No. Soc. Name Soc. Address Zone Status 1 1232S-GH NAV NIKETAN CGHS LTD B-83, AMAR COLONY, LAJPAT NAGAR, NEW DELHI : 110 024 South ACTIVE 2 1451ND-GH PREETI PRISHAD CGHS LTD. DB-84E, DDA FLATS, HARI NAGAR, NEW DELHI: 110 063 New Delhi ACTIVE 3 875E-GH NAV TARANG COOP. G/H SOCIETY LTD H-26, OLD GOBIND PURA EXT.,DELHI-51 East ACTIVE 4 724-INDL THE JAIN H/L COOP. INDL. (P) SOCIETY LTD. F413 GALI NO. 11, BHAGIRATH VIHAR, DELHI-94 North East ACTIVE THE BAKARWALA COOP. BRICKS KILN (I) 5 24W-INDL SOCIETY LTD. SURERE, NAJAFGARH, N. DELHI-43 West ACTIVE LIQUIDATE 6 24W-NMPS THE BAKARWALA COOP. M/P SOCIETY LTD. West D THE PANDWAL KHOODS COOP N.M.P SOCIETY South LIQUIDATE 7 32-NMPS LTD V.P.O PANDWAL KHOODS, NEW DELHI West D 8 505S-TC The Sikh Coop. Thrift & Credit Society Ltd. 61, Hemkunt Colony, New Delhi- South ACTIVE South 9 124-NMPS THE PALAM COOP N.M.P SOCIETY LTD V&PO, PALAM , NEW DELHI West ACTIVE 211NW- North 10 NMPS BAKAOLI COOL M/P SOCIETY LTD VILLAGE BAKAOLI, DELHI West DEFUNCT NON- 216NE- FUNCTION 11 NMPS THE BABARPUR M/P COOP. SOCIETY LTD. VILLAGE BABARPUR, SHAHDARA, DELHI-32 North East AL Chiragh Delhi Palti Yadram Coop. Thrift & Credit 12 230S-TC Sociey Ltd. 830 Chiragh Delhi,New Delhi-17 South ACTIVE 138NW- North 13 NMPS BUKHTAWAR PUR COOP.