Demographic Destinies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Behavioral Sciences: Essays in Honor of GEORGE A. LUNDBERG

The Behavioral Sciences: Essays in Honor of George A. Lundberg The Behavioral Sciences: Essays in Honor of GEORGE A. LUNDBERG edited by ALFRED DE GRAZIA RoLLoHANDY E. C. HARWOOD PAUL KURTZ published by The Behavioral Research Council Great Barrington, Massachusetts Copyright © 1968 by Behavioral Research Council Preface This volume of collected essays is dedicated to the memory of George A. Lundberg. It is fitting that this volume is published under the auspices of the Behavioral Research Council. George Lundberg, as its first President, and one of its founding members, was dedicated to the goals of the Behavioral Research Council: namely, the encouragement and development of behavioral science research and its application to the problems of men in society. He has been a constant inspiration to behavioral research not only in sociology, where he was considered to be a classic figure and a major influence but in the behavioral sciences in general. Part One of this volume includes papers on George Lundberg and his scientific work, particularly in the field of sociology. Orig inally read at a special conference of the Pacific Sociological Association (March 30-April 1, 1967), the papers are here pub lished by permission of the Society. Part Two contains papers not directly on George Lundberg but on themes and topics close to his interest. They are written by members of the Behavioral Research Council. We hope that this volume is a token, however small, of the pro found contribution that George Lundberg has made to the de velopment of the behavioral sciences. We especially wish to thank the contributors of the George A. -

Demographic Destinies

DEMOGRAPHIC DESTINIES Interviews with Presidents of the Population Association of America Interview with Kingsley Davis PAA President in 1962-63 This series of interviews with Past PAA Presidents was initiated by Anders Lunde (PAA Historian, 1973 to 1982) And continued by Jean van der Tak (PAA Historian, 1982 to 1994) And then by John R. Weeks (PAA Historian, 1994 to present) With the collaboration of the following members of the PAA History Committee: David Heer (2004 to 2007), Paul Demeny (2004 to 2012), Dennis Hodgson (2004 to present), Deborah McFarlane (2004 to 2018), Karen Hardee (2010 to present), Emily Merchant (2016 to present), and Win Brown (2018 to present) 1 KINGSLEY DAVIS PAA President in 1962-63 (No. 26). Interview with Jean van der Tak in Dr. Davis's office at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University, California, May 1, 1989, supplemented by corrections and additions to the original interview transcript and other materials supplied by Dr. Davis in May 1990. CAREER HIGHLIGHTS: (Sections in quotes come from "An Attempt to Clarify Moves in Early Career," Kingsley Davis, May 1990.) Kingsley Davis was born in Tuxedo, Texas in 1908 and he grew up in Texas. He received an A.B. in English in 1930 and an M.A. in philosophy in 1932 from the University of Texas, Austin. He then went to Harvard, where he received an M.A. in sociology in 1933 and the Ph.D. in sociology in 1936. He taught sociology at Smith College in 1934-36 and at Clark University in 1936-37. From 1937 to 1944, he was Chairman of the Department of Sociology at Pennsylvania State University, although he was on leave in 1940-41 and in 1942-44. -

The Chicago School of Sociology

Sociology 915 Professor Mustafa Emirbayer Spring Semester 2011 O f fice: 8141 Sewell Social Science Thursdays 5-8 PM Office Telephone: 262-4419 Classroom: 4314 Sewell Social Science Email: [email protected] Office Hours: Thursdays 12-1 PM http://ssc.wisc.edu/~emirbaye/ The Chicago School of Sociology Overview of the Course: This course will encompass every aspect of the Chicago School: its philosophic origins, historical development, theoretical innovations, use of ethnographic and other methods, and contributions to such areas as urban studies, social psychology, race relations, social organization and disorganization, ecology, and marginality. Chronologically, it will cover both the original Chicago School (interwar years) and the Second Chicago School (early postwar period). Readings: Because of the open-endedness of the syllabus, no books will be on order at the bookstore. Students are expected to procure their own copies of books they wish to own. A number of books (dozens) will be on reserve at the Social Science Reference Library (8th floor of Sewell Social Science Building). In addition, many selections will be available as pdf files at Learn@UW. For future reference, this syllabus will also be available at Learn@UW. Grading Format: Students’ grades for this course will be based on two different requirements, each of which will contribute 50% to the final grade. First, students will be evaluated on a final paper. Second, they will be graded on their class attendance and participation. More on each of these below. Final Paper: One week after the final class meeting of the semester (at 5 p.m. that day), a final paper will be due. -

Center for Studies in Demography and Ecology

Center for Studies in Demography and Ecology Some Evolving Thoughts on Leo F. Schnore as a Social Scientist by Avery M. Guest University of Washington UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON CSDE Working Paper No. 99-09 SOME EVOLVING THOUGHTS ON LEO F. SCHNORE AS A SOCIAL SCIENTIST Avery M. Guest Department of Sociology Box 353340 University of Washington Seattle, WA 98115 Draft: 04/09/99 I first encountered Leo on an autumn day in 1966 when, during my second graduate term, I was taking a course from him on Urbanism and Urbanization. Leo had actually missed the first few weeks of the course, and his friend Eric Lampard had ably filled in with a discussion of the long-term history of urbanization. Leo was a galvanizing figure in my life. Until that point, I did not see much future for myself as a sociologist. I had enjoyed sociology as a discipline at Oberlin College in Ohio, but what bothered me about it was the seeming abstractness of the subject matter. As presented to me by other faculty, there were many interesting concepts and ideas, but I failed to become engrossed in them because I could not determine their validity. At the time, I was contemplating a return to newspaper reporting which I greatly enjoyed because of its investigative quality, although I saw little of the conceptual overview that I appreciated from sociology. Leo brought it all together. He had a lot of stimulating, clear ideas about what was happening to cities in the United States. And he seemed wedded strongly to the position that ideas were largely accepted on the basis of empirical support. -

Sheraton-Boston Hotel· Boston • August 27-31, 1979 L

1979 Sheraton-Boston Hotel· Boston • August 27-31, 1979 l Lester F. Ward Carl C. Taylor William G. Sumner Louis Wirth Franklin H. Giddings E. Franklin Frazier Albion W. Small Talcott Parsons Edward A. Ross Leonard S. Cottrell, Jr. George E. Vincent Robert C. George E. Howard Dorothy Swaine Thomas Charles H. Cooley Samuel A. Stouffer Frank W. Blackmar Florian Znaniecki James Q. Dealey Donald Young Edward C. Hayes Herbert Blumer James P. Lichtenberger Robert K. Merton Ulysses G. Weatherly Robin M. Williams, Jr. Charles A. Ellwood Kingsley Davis Robert E. Park Howard Becker John L. Gillin Robert E.L. Faris William I. Thomas Paul F. Lazarsfeld John M. Gillette Everett C. Hughes William F. Ogburn George C. Homans Howard W. Odum Pitirim A. Sorokin Emory S. Bogardus Wilbert E. Moore Luther L. Bernard Charles P. Loomis Edward B. Reuter Philip M. Hauser Ernest W. Burgess Arnold M. Rose F. Stuart Chapin Ralph H. Turner Henry P. Fairchild Reinhard Bendix Ellsworth Faris William H. Sewell Frank H. Hankins William J. Goode Edwin H. Sutherland Mirra Komarovsky Robert M. MacIver Peter M. Blau Stuart A. Queen Lewis A. Coser Dwight Sanderson Alfred McClung Lee George A. Lundberg J. Milton Yinger Rupert B. Vance Amos H. Hawley Kimball Young Executive Office 1722 N Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 (202) 833-3410 The American Sociological Association 1979 Seventy·Fourth Annual eeting Sheraton-Boston Hotel·' Boston • August 27-31, 1979 3 THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THEORY AND RESEARCH: AN ASSESSMENT OF FUNDAMENTAL PROBLEMS AND THEIR POSSffiLE RESOLUTION Every discipline needs to be continuously concerned about the quality, as well as the quantity, of what iUs producing and the ways in which its knowledge and thought processes are transmitted to the outside public. -

AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL STATEMEN T Otis Dudley Duncan My Parents Were Both Members of Large Farm Families in Northeast Texas in The

AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL STATEMEN T Otis Dudley Dunca n My parents were both members of large farm families in northeast Texa s in the early years of this cent, .rv . Although their levels of living wer e low and their upbringing arduous, their aspirations were high . They met a t college during World War I, so that I was a member of the "baby boom" tha t flared up briefly after the War . My father became a public school teacher , principal, and superintendent to earn his iiveliheod while trying to pursu e graduate studies . We moved around Texas a good deal as he sought bette r jobs and spent summers at college . Finally, he was able to enter upo n Ph .D . study at the University of Minnesota, where he yes strongly influence d by Fitirim A . Sorokin . But the sojourn came to unhappy end, as my fathe r was failed in his attempt at his preliminary examinations . There is a grea t deal more that could be told about his struggle fir an education, but t o cut it short, I mention thee he received his Ph .7 . at the same time I r e ceive d my B .A ., both at Louisiana State University in 19-1 . in the meantime, in 1929, 7_ father had joined the faculty of Oklahom a A . & T . College (Styli titer, Ohia .) - Liter calla] Oklahoma State University - - as a rural sociologist . In 1936, he was asked tc form a de partment o f sociology, and he remained its head until his retirement . Until I was eight years old, therefore, I was "on the road " with my parents, the son of a school teacher, graduate s__dent, and beginnin g professor . -

Kingsley Davis 1908–1997

Kingsley Davis 1908–1997 A Biographical Memoir by Geoffrey McNicoll ©2019 National Academy of Sciences. Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. KINGSLEY DAVIS August 20, 1908–February 27, 1997 Elected to the NAS, 1966 Kingsley Davis was a significant figure in American sociology of the mid-twentieth century and by many esti- mations the leading social demographer of his generation. He made influential contributions to social stratification theory and to the study of family and kinship. He was an early theorist of demographic transition—the emergence of low-mortality, low-fertility regimes in industrializing societies—and a protagonist in major and continuing debates on policy responses to rapid population growth in low-income countries. Davis held faculty appointments at a sucession of leading universities, for longest at the University of California, Berkleley. He was honored by his peers in both sociology By Geoffrey McNicoll and demography: president of the America Sociological Association in 1959 and of the Population Association of America in 1962-’63. He was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1966, the first sociologist to be a member. Kingsley Davis was born in Tuxedo, Texas, a small community near Abilene, in 1908. His parents were Joseph Dyer Davis, a physician, and Winifred Kingsley Davis; he was a collateral descendant of Jefferson Davis. He took his baccalaureate from the University of Texas in 1930. (Revisiting the campus decades later as a distinguished professor, he allowed that he would not have qualified for admission under later, more stringent criteria.) Two years later at the same institution he received an MA in philosophy with a thesis on the moral philosophy of Bertrand Russell. -

Amos Hawley: Apioneer Inhumanecology by David B

Amos Hawley: A Pioneer in Human Ecology by John D. Kasarda, University of North ness and early death took McKenzie from Theoretical Innovation Carolina at Chapel Hill Michigan in 1940, his protégé succeeded It was his more than 100 scholarly works, him. There, Amos rose through the ranks though, for which Amos will be most th mos Henry Hawley, 69 President of from instructor to professor and served remembered. His academic career is best Athe American Sociological as chair of the department from defined by an early book, Human Ecology: Association, died in Chapel Hill, 1951 to 1962. A Theory of Community Structure (1950). NC, on August 31, 2009, at the age Michigan’s Sociology That book remains the most comprehensive of 98. A seminal theorist, Amos Department was in its heyday statement of the ecological approach to social helped revitalize macrosociology during Amos’ decade as chair, organization. In many ways, it was a major in the 1950s and 60s via his refor- leading the way with its Survey departure from previous work in sociologi- mulation, extension, and codifica- Research Center, Center for cal human ecology. Amos was able to distill tion of human ecological models. Group Dynamics, Population prior research and field observations of He left an indelible imprint on Center, and Detroit Area Study. human ecologists into a codified theatrical our discipline by his writings It also had many distinguished framework that explained characteristics of and those of many of his students. Amos Hawley faculty ranging from social 1910-2009 social organization as the product of a popu- Stately, yet always modest, his bril- psychologists to demographers, lation adapting to its environment. -

Xie, Yu, Leo A. Goodman, Robert M. Hauser, David L. Featherman, And

Obituaries Otis Dudley Duncan (1921-2004) Otis Dudley Duncan, one of the most influential sociologists of the 20th century, died of prostate cancer in Santa Barbara, California, on November 16, 2004. Duncan was instrumental in advancing the discipline of sociology through the use of advanced quantitative methods. Duncan was “the most important quantitative sociologist in the world in the latter half of the 20th century,” said Leo Goodman, University of California-Berkeley. Duncan’s best-known work is a 1967 book that he coauthored with the late Peter M. Blau, The American Occupational Structure, which received the American Sociological Association Sorokin Award for most distinguished scholarly publication (1968). Based on quantitative analyses of the first large national survey of social mobility in the United States, the book elegantly depicts the process of how parents transmit their social standing to their children, particularly through affecting the children’s education. This work was subsequently elaborated by Duncan and other scholars, to include the role of cognitive ability, race, and other factors in the transmission of social standing from one generation to the next. The book’s impact went far beyond its analyses of occupational mobility. Using survey data and statistical techniques, the book showed how an important sociological topic could be analyzed effectively and rigorously with appropriate quantitative methods. The work helped inspire a new generation of sociologists to follow and pursue quantitative sociology. Robert -

TRANSFORMATIONS Mprntiw Study Of& Tm~Zsfmmations

TRANSFORMATIONS mprntiw study of& tm~zsfmmations CSST WORKING PAPERS The University of Michigan Ann Arbor "What We Talk About When We. Talk About History: The Conversations of History and Sociology" Terrence McDonald CSST Working CRSO Working Paper #52 Paper #44 2 October 1990 What We ~alkAbout When We Talk About ~istory: The Conversations of History and.Sociology1 Terrence J. McDonald As the epigraph for his enormously influential 1949 book Social Theorv and Social Structure Robert K. Merton selected the now well known opinion of Alfred North Whitehead that Ita science which hesitates to forget its founders is lost.tt And both history and sociology have been struggling with the implications of that statement ever since. On the one hand, it was the belief that it was possible to forget one's ttfounderswthat galvanized the social scientists (including historians) of Mertonfs generation to reinvent their disciplines. But on the other hand, it was the hubris of that view that ultimately undermined the disciplinary authority that they set out to construct, for in the end neither their propositions about epistemology or society could escape from "history."2 Social and ideological conflict in American society undermined the correspondence between theories of consensus and latent functions and the Itrealitynthey sought to explain; the belief in a single, scientific, transhistorical road to cumulative knowledge was assaulted by theories of paradigms and incommensurability; marxist theory breached the walls of both idealism and the ideology of scientific neutrality only to be overrun, in its turn, by the hordes of the ttpoststt:post-positivism, post-modernism, post-marxism, post-structuralism, and others too numerous to mention. -

Public Lecture Series Speakers: 1936 – 2019

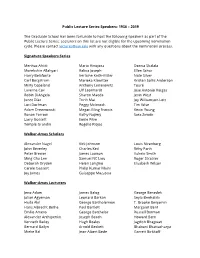

Public Lecture Series Speakers: 1936 – 2019 The Graduate School has been fortunate to host the following speakers as part of the Public Lecture Series. Lecturers on this list are not eligible for the upcoming nomination cycle. Please contact [email protected] with any questions about the nomination process. Signature Speakers Series Menhaz Afridi Maria Hinojosa Donna Shalala Morehshin Allahyari Ralina Joseph Ellen Schur Harry Belafonte Verlaine Keith-Miller Nate Silver Carl Bergstrom Marieka Klawitter Kristen Soltis Anderson Misty Copeland Anthony Leiserowitz Touré Laverne Cox Ulf Leonhardt Jose Antonio Vargas Robin DiAngelo Sharon Maeda Jevin West Junot Díaz Trinh Mai Joy Williamson-Lott Lori Dorfman Peggy McIntosh Tim Wise Adam Drewnowski Megan Ming Francis Kevin Young Ronan Farrow Kathy Najimy Sara Zewde Larry Gossett Emile Pitre Temple Grandin Rogelio Riojas Walker-Ames Scholars Alexander Nagel Kirk Johnson Louis Nirenberg John Beverley Charles Keil Rithy Panh Peter Brewer James Lawson Valerie Smith Ming Cho Lee Samuel NC Lieu Roger Strasser Deborah Dryden Helen Longino Elizabeth Wilson Carole Gassert Philip Kumar Maini Joy James Guiseppe Mazzotta Walker-Ames Lecturers Jeno Adam James Balog George Benedek Julian Agyeman Leonard Barkan Seyla Benhabib Huda Akil George Bartholemew T. Brooke Benjamin Hans Albrecht Bethe Paul Bartlett Margaret Bent Emilio Amero George Batchelor Russell Berman Alexander Archipenko Joseph Beach Howard Bern Kenneth Bailey Hugh Beales Jagdish Bhagwati Bernard Bailyn Arnold Beckett Bhabani Bhattacharya Mieke Bal Jean-Albert Bede Garrett Birkhoff Alan Bittles Alfred Chandler, Jr. Robert Dicke J. Bjerknes Li Chi Liselotte Dieckmann Felix Bloch Brock Chisholm Jean Dieudonne Bruce Blumberg Gustave Choquet Andrea (Andy) DiSessa Larry Bobo Ralph Cicerone Stuart Dodd Christoph Bode Marion Clawson Denis Donoghue Bart Bok Cornell Clayton Sterling Dow Bert Bolin William Clebsch Curt Ducasse Paul Bonifas JM Coetzee John Dunning Gabriel Bonno Philip Cohen J. -

Eugenics in the Post-War United States

Working Papers on the Nature of Evidence: How Well Do “Facts” Travel? No. 12/06 Confronting the Stigma of Perfection: Genetic Demography, Diversity and the Quest for a Democratic Eugenics in the Post-war United States Edmund Ramsden © Edmund Ramsden Department of Economic History London School of Economics August 2006 how ‘facts’ “The Nature of Evidence: How Well Do ‘Facts’ Travel?” is funded by The Leverhulme Trust and the E.S.R.C. at the Department of Economic History, London School of Economics. For further details about this project and additional copies of this, and other papers in the series, go to: http://www.lse.ac.uk/collection/economichistory/ Series Editor: Dr. Jon Adams Department of Economic History London School of Economics Houghton Street London WC2A 2AE Email: [email protected] Tel: +44 (0) 20 7955 6727 Fax: +44 (0) 20 7955 7730 Confronting the Stigma of Perfection: Genetic Demography, Diversity and the Quest for a Democratic Eugenics in the Post- war United States1 Edmund Ramsden Abstract Eugenics has played an important role in the relations between social and biological scientists of population through time. Having served as a site for the sharing of data and methods between disciplines in the early twentieth century, scientists and historians have tended to view its legacy in terms of reduction and division - contributing distrust, even antipathy, between communities in the social and the biological sciences. Following the work of Erving Goffman, this paper will explore how eugenics has, as the epitome of “bad” or “abnormal” science, served as a “stigma symbol” in the politics of boundary work.