Environmental Challenges and Human Security in the Himalaya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gross National Happiness Commission the Royal Government of Bhutan

STRATEGIC PROGRAMME FOR CLIMATE RESILIENCE (SPCR) UNDER THE PILOT PROGRAMME FOR CLIMATE RESILIENCE (PPCR) Climate-Resilient & Low-Carbon Sustainable Development Toward Maximizing the Royal Government of Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness GROSS NATIONAL HAPPINESS COMMISSION THE ROYAL GOVERNMENT OF BHUTAN FOREWORD The Royal Government of Bhutan (RGoB) recognizes the devastating impact that climate change is having on Bhutan’s economy and our vulnerable communities and biosphere, and we are committed to address these challenges and opportunities through the 12th Five Year Plan (2018-2023). In this context, during the 2009 Conference of the Parties 15 (COP 15) in Copenhagen, RGoB pledged to remain a carbon-neutral country, and has successfully done so. This was reaffirmed at the COP 21 in Paris in 2015. Despite being a negative-emission Least Developed Country (LDC), Bhutan continues to restrain its socioeconomic development to maintain more than 71% of its geographical area under forest cover,1 and currently more than 50% of the total land area is formally under protected areas2, biological corridors and natural reserves. In fact, our constitutional mandate declares that at least 60% of Bhutan’s total land areas shall remain under forest cover at all times. This Strategic Program for Climate Resilience (SPCR) represents a solid framework to build the climate- resilience of vulnerable sectors of the economy and at-risk communities across the country responding to the priorities of NDC. It also offers an integrated story line on Bhutan’s national -

Pakistan 2005 Earthquake Preliminary Damage and Needs Assessment

Pakistan 2005 Earthquake Preliminary Damage and Needs Assessment Prepared By Asian Development Bank and World Bank Islamabad, Pakistan November 12, 2005 CURRENCY AND EQUIVALENTS Currency Unit = Pakistan Rupee US$1 = PKR 59.4 FISCAL YEAR July 1 - June 30 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ADB Asian Development Bank LPG Liquefied Petroleum Gas ADP Annual Development Plans MOH Ministry of Health AIDS Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome MOWP Ministry of Water and Power AEZs Agro-Ecological Zones MPNR Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Resources AJK Azad Jammu Kashmir MSW Municipal Solid Waste AJKED Electricity Department of Azad J. Kashmir NCHD National Commission for Human Development ARI Acute Respiratory Infection NGOs Non-Governmental Organizations CAA Civil Aviation Authority NHA National Highway Authority CAS Country Assistance Strategy NWFP North West Frontier Province CFAA Country Financial Accountability Assessment OMC Oil Marketing Companies CISP Community Infrastructure and Services Project P&DD Planning and Development Department CMU Concrete Masonry Unit PESCO Peshawar Electricity Supply Company DAC Disaster Assessment and Coordination PHC Primary Health Care DECC District Emergency Coordination Committee PHED Public Health Engineering Department DFID Department for International Development PIFRA Project to Improve Financial Reporting and DPL Development Policy Loan Auditing ECLAC Economic Commission for Latin America and PIHS Pakistan Integrated Household Survey the Caribbean PPAF Pakistan Poverty Alleviation Fund EMG Emergency Management -

Tempa-Bhutan-Tigers-2019.Pdf

Biological Conservation 238 (2019) 108192 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Biological Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon The spatial distribution and population density of tigers in mountainous T terrain of Bhutan ⁎ Tshering Tempaa,b, , Mark Hebblewhitea, Jousha F. Goldbergc, Nawang Norbud,e, Tshewang R. Wangchukf, Wenhong Xiaoa, L. Scott Millsa,g a Wildlife Biology Program, W.A. Franke College of Forestry and Conservation, University of Montana, Missoula, MT-59801, USA b Global Tiger Center, Department of Forests and Park Services, Ministry of Agriculture and Forests, Bhutan c Department of Evolution, Ecology and Organismal Biology, University of California, Riverside, CA 92521, USA d Bhutan Ecological Society, Chubachu, Thimphu, Bhutan e Center for Himalayan Environment and Development Studies, School for Field Studies, Bhutan f Bhutan Foundation, 21 Dupont Circle, NW, Washington DC-20036, USA g Office of Research and Creative Scholarship, University of Montana, Missoula, MT 59801,USA ABSTRACT Habitat loss, prey depletion, and direct poaching for the illegal wildlife trade are endangering large carnivores across the globe. Tigers (Panthera tigris) have lost 93% of their historical range and are experiencing rapid population declines. A dominant paradigm of current tiger conservation focuses on conservation of 6% of the presently occupied tiger habitat deemed to be tiger source sites. In Bhutan, little was known about tiger distribution or abundance during the time of such classi- fication, and no part of the country was included in the so-called 6% solution. Here we evaluate whether Bhutan is a potential tiger source sitebyrigorously estimating tiger density and spatial distribution across the country. We used large scale remote-camera trapping across n = 1129 sites in 2014–2015 to survey all potential tiger range in Bhutan. -

Himalayan Borders and Borderlands: Mobility, State Building, and Identity

Himalayan Borders and Borderlands: Mobility, State Building, and Identity This review article engages with recent ethnographic research on ‘borders’ and ‘borderlands’ in the Himalayan region. We examine how recent scholarship published primarily between 2012-2018 engages with borderland theory as it intersects with issues of state building, ethnicity, language, religion, and tourism. As the scholarly canon moves away from disparate areas studies approaches, this paper investigates how Himalayan scholarship views borders as comprising a multivariate geographical, cultural, and political network of history and relationships undergoing continual transformation. As emerging scholars from both within and outside the Himalaya, we separate the article into four sub- sections that each connect to our respective interests. Our intention is not to propose an alternative conceptual framework or set of terminologies to borderland studies, but to bring together various inter-disciplinary approaches that view borders as sites of continuity and discontinuity, with the power to transform livelihoods for the better and at times perpetuate forms of violence and inequality. Keywords: borders, borderlands, Himalaya, mobility, state building, identity 1 Introduction How do Himalayan borders become contested spaces of continuity and discontinuity in relation to the borderland communities that occupy them, and the non-inhabitants that relate to them? How does this tension link to ongoing projects of mobility, state formation, and identity politics? This article reviews recent ethnographic research on Himalayan borders and borderlands surrounding state building, development, tourism, ethnicity, language, and religion, with a focus on material published between 2012-2018. We critically engage with notions of ‘borders’ and ‘borderlands’, to explore how recent scholarship has engaged with changing borderland theory as it reflects on Himalayan place and personhood. -

GLIMPSES of FORESTRY RESEARCH in the INDIAN HIMALAYAN REGION Special Issue in the International Year of Forests-2011

Special Issue in the International Year of Forests-2011 i GLIMPSES OF FORESTRY RESEARCH IN THE INDIAN HIMALAYAN REGION Special Issue in the International Year of Forests-2011 Editors G.C.S. Negi P.P. Dhyani ENVIS CENTRE ON HIMALAYAN ECOLOGY G.B. Pant Institute of Himalayan Environment & Development Kosi-Katarmal, Almora - 263 643, India BISHEN SINGH MAHENDRA PAL SINGH 23-A, New Connaught Place Dehra Dun - 248 001, India 2012 Glimpses of Forestry Research in the Indian Himalayan Region Special Issue in the International Year of Forests-2011 © 2012, ENVIS Centre on Himalayan Ecology G.B. Pant Institute of Himalayan Environment and Development (An Autonomous Institute of Ministry of Environment and Forests, Govt. of India) Kosi-Katarmal, Almora All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written consent of the copyright owner. ISBN: 978-81-211-0860-7 Published for the G.B. Pant Institute of Himalayan Environment and Development by Gajendra Singh Gahlot for Bishen Singh Mahendra Pal Singh, 23-A, New Connaught Place, Dehra Dun, India and Printed at Shiva Offset Press and composed by Doon Phototype Printers, 14, Old Connaught Place, Dehra Dun India. Cover Design: Vipin Chandra Sharma, Information Associate, ENVIS Centre on Himalayan Ecology, GBPIHED Cover Photo: Forest, agriculture and people co-existing in a mountain landscape of Purola valley, Distt. Uttarkashi (Photo: G.C.S. Negi) Foreword Amongst the global mountain systems, Himalayan ranges stand out as the youngest and one of the most fragile regions of the world; Himalaya separates northern part of the Asian continent from south Asia. -

An Account of a Journey Across Valleys and Mountains to Provide Training to People on Collection of Medicinal Plants

An account of a journey across valleys and mountains to provide training to people on collection of medicinal plants ... towards sustainability of traditional medical services in Bhutan Kinga Jamphel Head, Pharmaceutical & Research Unit, ITMS Ever since the establishment of traditional medicine (TM) services in the country in 1967, most of the high altitude medicinal raw materials have been collected from Lingshi. It is important to rotate the collection sites at certain intervals in order to enable the natural resources to regenerate. A survey on alternate sourcing conducted at Bumthang in 2006 revealed that around 18 medicinal plants could be collected. To provide training on sustainable collection and discuss on the logistics for transportation of medicinal plants, a team visited the high altitude areas of Bumthang. The last few days before the departure were filled with excitement and nervousness, especially as the journey would involve long walks across high mountain areas where stamina and body fitness would be put on test. Food supplies and logistics were organized. It was 10th of October 2007. I woke up early and checked my luggage for all important things - some medicines, a knife, a sleeping bag, a mat, clothes, a torch, a plate, a mug, etc. I prayed for a safe journey and said goodbye to my family. The other members of the team Drungtsho Gempo Dorji, Ugyen, Jamyang Loday and Tshewang Rinzin joined and the long journey began from Thimphu at 7.30 AM. As we traveled along the East-West national highway cross Dochula, Pelela and Yotongla passes we were excited thinking about the days ahead. -

Earthquake 2005: Some Implications for Environment and Human Capital

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Earthquake 2005: Some Implications for Environment and Human Capital Hamdani, Nisar Hussain and Shah, Syed Akhter Hussain Pakistan Institute of DEvelopment EConomics Islamabad Pakistan 2005 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/9519/ MPRA Paper No. 9519, posted 11 Jul 2008 04:58 UTC FJW University Rawalpindi , AJ&K Muzaffarabad and Higher Education Commission Islamabad-Pakistan Earthquake 2005: Some Implications for Environment and Human Capital Dr. Syed Nisar Hussain Hamdani* ` & Syed Akhter Hussain Shah** Loss of human capital in the form of skills and experiences is one of the outcomes of any natural hazard such as earthquake, drought, famine, and floods. Generally such losses have many implications for further growth of individuals, communities and nations. Disaster management and risk assessment has established a new need to constitute a paradigm of planning frameworks to develop modules for dealing with interactive rehabilitation and reconstruction activities. However, such management still lacks due attention in perspective of the remedy of human capital loss particularly in environmental management. This paper discusses the post-disaster situations with respect to human capital flow and stock losses and some of their implications and suggests some measures to apply in the earthquake-affected areas of Azad Kashmir and NWFP. Introduction A sustainable environment facilitates directly and indirectly to the strengthening of economic growth, socio-cultural demographic uplift, infrastructural buildup, positive external generation, and improving beyond preserving levels the ‘quality of life for humans’. Further it is complementary to economic growth for long run human development objectives as well, where it significantly affects human capital, its accumulation and the overall environment. -

The Project for National Disaster Management Plan in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan

NATIONAL DISASTER MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY (NDMA) THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF PAKISTAN THE PROJECT FOR NATIONAL DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN IN THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF PAKISTAN FINAL REPORT NATIONAL MULTI-HAZARD EARLY WARNING SYSTEM PLAN MARCH 2013 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. CTI ENGINEERING INTERNATIONAL PT OYO INTERNATIONAL CORPORATION JR 13-001 NATIONAL DISASTER MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY (NDMA) THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF PAKISTAN THE PROJECT FOR NATIONAL DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN IN THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF PAKISTAN FINAL REPORT NATIONAL MULTI-HAZARD EARLY WARNING SYSTEM PLAN MARCH 2013 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. CTI ENGINEERING INTERNATIONAL OYO INTERNATIONAL CORPORATION The following foreign exchange rate is applied in the study: US$ 1.00 = PKR 88.4 PREFACE The National Disaster Management Plan (NDMP) is a milestone in the history of the Disaster Management System (DRM) in Pakistan. The rapid change in global climate has given rise to many disasters that pose a severe threat to the human life, property and infrastructure. Disasters like floods, earthquakes, tsunamis, droughts, sediment disasters, avalanches, GLOFs, and cyclones with storm surges are some prominent manifestations of climate change phenomenon. Pakistan, which is ranked in the top ten countries that are the most vulnerable to climate change effects, started planning to safeguard and secure the life, land and property of its people in particular the poor, the vulnerable and the marginalized. However, recurring disasters since 2005 have provided the required stimuli for accelerating the efforts towards capacity building of the responsible agencies, which include federal, provincial, district governments, community organizations, NGOs and individuals. Prior to 2005, the West Pakistan National Calamities Act of 1958 was the available legal remedy that regulated the maintenance and restoration of order in areas affected by calamities and relief against such calamities. -

Higher-State-Of-Being-Full-Lowres.Pdf

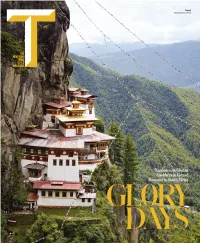

HIGHER STIn the vertiginousAT mountainsE of Bhutan, where happiness is akin to holiness, bicycling has become much more than a national pastime. It’s a spiritual journey. BY JODY ROSEN OF BEINPHOTOGRAPHSG BY SIMON ROBERTS N BHUTAN, THERE IS A KING who rides a bicycle up and down the mountains. Like many stories you will hear in this tiny Himalayan nation, it sounds like a fairy tale. In fact, itís hard news. Jigme Singye IWangchuck, Bhutanís fourth Druk Gyalpo, or Dragon King, is an avid cyclist who can often be found pedaling the steep foothills that ring the capital city, Thimphu. All Bhutanese know about the kingís passion for cycling, to which he has increasingly devoted his spare time since December 2006, when he relinquished the crown to his eldest son. In Thimphu, many tell tales of close encounters, or near-misses ó the time they pulled over their car to chat with the bicycling monarch, the time they spotted him, or someone who looked quite like him, on an early-morning ride. If you spend any time in Thimphu, you may soon find yourself scanning its mist-mantled slopes. That guy on the mountain bike, darting out of the fog bank on the road up near the giant Buddha statue: Is that His Majesty? SOUL CYCLE The fourth king is the most beloved figure in A rider in the Tour of the Dragon, a modern Bhutanese history, with a biography 166.5-mile, one-day that has the flavor of myth. He became bike race through the mountains of Bhutan, Bhutanís head of state in 1972 when he was just alongside the Druk 16 years old, following the death of his father, Wangyal Lhakhang Jigme Dorji Wangchuck. -

Multihazard Early Warning System

Government of Pakistan Cabinet Division National Plan: Strengthening National Capacities for Multi Hazard Early Warning and Response System Phase: I Prepared by Dr. Qamar-uz-Zaman Chaudhry Director General Pakistan Meteorological Department Under the guidance of Mr. Ejaz Rahim Secretary, Cabinet Division May, 2006 Phase-I of National Plan : Submitted for seeking funding from the consortium formed in response to President Clinton’s (The UN Special Envoy for Tsunami Recovery) initiative urging developing countries in the Indian Ocean Region to develop national plans for the establishment of Early Warning and Response Systems. 2 CONTENTS Executive Summary 1. Introduction 1.1 Geography 1.2 Seismicity / Earthquakes 1.3 Tsunami 1.4 Tropical Cyclone 1.5 Drought 1.6 Floods 2. Disaster Management Policy at National Level 3. National Strategy for Disaster Management 4. Organizations with overall disaster related responsibilities 4.1 Emergency Relief Cell (ERC) 4.2 Pakistan Meteorological Department (PMD) 4.3 Federal Flood Commission (FFC) 4.4 National Crisis Management Cell (NCMC) 4.5 Civil Defence 4.6 Provincial Relief Departments 4.7 Provincial Irrigation Departments 4.8 Provincial Health Departments 4.9 Provincial Agriculture & Livestock Department 4.10 Provincial Food Departments 4.11 Communication & Works 4.12 Planning & Development Departments 4.13 Army 4.14 Police Department 4.15 Dams Safety Council 5. Disaster Management in Regional Bodies 5.1 South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) 5.1.1 The SAARC Regional Study on the -

1.3 Seismic Hazard

1 Introduction Natural disasters inflicted by earthquakes, landslides, flood, drought, cyclone, forest fire, volcanic eruptions, epidemics etc. keep happening in some parts or the other around the globe leading to loss of life, damage to properties and causing widespread socio-economic disruptions. EM- DAT, a global disaster database maintained by the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED) in Brussels, records more than 600 disasters globally every year (http://www. cred.be). Earthquakes are the major menace to the mankind killing thousands of people every year in different parts of the globe. An estimated average of 17,000 persons per year has been killed in the 20th century itself. Statistics taken for the period 1973-1997 (http://www.cred.be), organized in 5-year bins, exhibit that earthquakes are amongst the disasters with larger death impact as depicted in Figure 1.1 even though the occurrences of flood events are twice per year. According to the International Disaster database (i.e. CRED) the total human fatality occurred in Asia for the period between 1900 to 2015 is estimated to be 18,23,324 persons while in case of only the Indian subcontinent the casualty is estimated to be around 78,209 with total economy loss of 5222.7 million (US$). Thus earthquakes are considered to be one of the worst among all the natural disasters. Figure 1.1 Comparison amongst different types of natural catastrophes (after Ansal, 2004). A comparative analysis performed by CRED in terms of total damage in billions of US$ reportedly caused by natural disasters as shown in Figure 1.2 illustrates that Asia is more prone to earthquake disaster than any other continental regions in the world. -

Ground Water Scenario of Himalaya Region, India

Hkkjr ds fgeky;h {ks=k dk Hkwty ifjn`'; Ground Water Scenario of Himalayan Region, India laiknu@Edited By: lq'khy xqIrk v/;{k Sushil Gupta Chairman Central Ground Water Board dsanzh; Hkwfe tycksMZ Ministry of Water Resources ty lalk/ku ea=kky; Government of India Hkkjr ljdkj 2014 Hkkjr ds fgeky;h {ks=k dk Hkwty ifjn`'; vuqØef.kdk dk;Zdkjh lkjka'k i`"B 1- ifjp; 1 2- ty ekSle foKku 23 3- Hkw&vkd`fr foKku 34 4- ty foKku vkSj lrgh ty mi;kst~;rk 50 5- HkwfoKku vkSj foorZfudh 58 6- Hkwty foKku 73 7- ty jlk;u foKku 116 8- Hkwty lalk/ku laHkko~;rk 152 9- Hkkjr ds fgeky;h {ks=k esa Hkwty fodkl ds laca/k esa vfHktkr fo"k; vkSj leL;k,a 161 10- Hkkjr ds fgeky;h {ks=k ds Hkwty fodkl gsrq dk;Zuhfr 164 lanHkZ lwph 179 Ground Water Scenario of Himalayan Region of India CONTENTS Executive Summary i Pages 1. Introduction 1 2. Hydrometeorology 23 3. Geomorphology 34 4. Hydrology and Surface Water Utilisation 50 5. Geology and Tectonics 58 6. Hydrogeology 73 7. Hydrochemistry 116 8. Ground Water Resource Potential 152 9. Issues and problems identified in respect of Ground Water Development 161 in Himalayan Region of India 10. Strategies and plan for Ground Water Development in Himalayan Region of India 164 Bibliography 179 ifêdkvks dh lwph I. iz'kklfud ekufp=k II. Hkw vkd`fr ekufp=k III. HkwoSKkfud ekufp=k d- fgeky; ds mRrjh vkSj if'peh [kaM [k- fgeky; ds iwohZ vkSj mRrj iwohZ [kaM rFkk iwoksZRrj jkT; IV.