Lessons from Lincolnshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lincolnshire Posy

CONDUCTOR 04005975 Two Movements from LINCOLNSHIRE POSY PERCY ALDRIDGE GRAINGER Arranged by MICHAEL SWEENEY INSTRUMENTATION 1 - Full Score 8 - Flute Part 1 2 - Oboe 6 - B% Clarinet/B% Trumpet 4 - Violin 6 - B% Clarinet/B% Trumpet Part 2 2 - E% Alto Saxophone 4 - Violin 4 - B% Clarinet 2 - B% Tenor Saxophone % % Part 3 2 - E Alto Saxophone/E Alto Clarinet 2 - F Horn 2 - Violin 4 - Viola 4 - B% Tenor Saxophone/Baritone T.C. 2 - F Horn Part 4 4 - Trombone/Baritone B.C./Bassoon 2 - Cello 2 - B% Bass Clarinet 4 - Trombone/Baritone B.C./Bassoon 2 - Baritone T.C. Part 5 2 - Cello 2 - E% Baritone Saxophone 4 - Tuba 2 - String/Electric Bass 2 - Percussion 1 Snare Drum, Bass Drum 2 - Percussion 2 Sus. Cym. 2 - Mallet Percussion Bells, Xylophone, Chimes, Crotales 1 - Timpani Additional Parts U.S. $2.50 Score (04005975) U.S. $7.50 8 88680 94789 7 HAL LEONARD Two Movements from FLEX-BAND SERIES LINCOLNSHIRE POSY PERCY ALDRIDGE GRAINGER Duration – 2:15 (Œ = 72-76) Arranged by MICHAEL SWEENEY Slowly flowingly Horkstow Grange 5 PART 1 Cl. preferred bb 4 a2 œ œ œ œ 5 œ. œ œ œ 4 œ œ œ œ 5 œ œ ˙œœ 4 œ œ œ œ œ œ œ Flute/Oboe & 4 œ œ 4 ˙ 4 œ 4 4 œ œ P F P F 4 a2 5 4 5 4 B¯ Clarinet/ & 4 4 œ. œ 4 4 œ œ 4 œ œ B¯ Trumpet œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙œœ œ œ œ œ œ œ Pœ ˙ F P F œ ≤ ≥ ≤ ≥ ≥ bb 4 5 4 5 4 Violin & 4 œ 4 œ. -

Lincolnshire Posy Abbig

A Historical and Analytical Research on the Development of Percy Grainger’s Wind Ensemble Masterpiece: Lincolnshire Posy Abbigail Ramsey Stephen F. Austin State University, Department of Music Graduate Research Conference 2021 Dr. David Campo, Advisor April 13, 2021 Ramsey 1 Introduction Percy Grainger’s Lincolnshire Posy has become a staple of wind ensemble repertoire and is a work most professional wind ensembles have performed. Lincolnshire Posy was composed in 1937, during a time when the wind band repertoire was not as developed as other performance media. During his travels to Lincolnshire, England during the early 20th century, Grainger became intrigued by the musical culture and was inspired to musically portray the unique qualities of the locals that shared their narrative ballads through song. While Grainger’s collection efforts occurred in the early 1900s, Lincolnshire Posy did not come to fruition until it was commissioned by the American Bandmasters Association for their 1937 convention. Grainger’s later relationship with Frederick Fennell and Fennell’s subsequent creation of the Eastman Wind Ensemble in 1952 led to the increased popularity of Lincolnshire Posy. The unique instrumentation and unprecedented performance ability of the group allowed a larger audience access to this masterwork. Fennell and his ensemble’s new approach to wind band performance allowed complex literature like Lincolnshire Posy to be properly performed and contributed to establishing wind band as a respected performance medium within the greater musical community. Percy Grainger: Biography Percy Aldridge Grainger was an Australian-born composer, pianist, ethnomusicologist, and concert band saxophone virtuoso born on July 8, 1882 in Brighton, Victoria, Australia and died February 20, 1961 in White Plains, New York.1 Grainger was the only child of John Harry Grainger, a successful traveling architect, and Rose Annie Grainger, a self-taught pianist. -

Discography Percy Grainger Compiled by Barry Peter Ould Mainly Piano

Discography Percy Grainger compiled by Barry Peter Ould mainly piano Percy Grainger (Percy Grainger, piano) – includes: PRELUDE AND FUGUE IN A MINOR (Bach); TOCCATA AND FUGUE IN D MINOR (Bach); FANTASY AND FUGUE IN G MINOR (Bach); SONATA NO.2 IN B-FLAT MINOR op. 35 (Chopin); ETUDE IN B MINOR op. 25/10 (Chopin); SONATA NO.3 IN B MINOR op. 58 (Chopin). Biddulph Recordings LHW 010 (12 tracks – Total Time: 76:08) Percy Grainger (Percy Grainger, piano) – includes: SONATA NO.2 IN G MINOR op.22 (Schumann); ROMANCE IN F-SHARP op. 28/2 (Schumann); WARUM? (from op. 12) (Schumann); ETUDES SYMPHONIQUES (op. 13) (Schumann); WALTZ IN A-FLAT op. 39/15 (Brahms); SONATA NO.3 IN F MINOR op. 5 (Brahms). Biddulph Recordings LHW 008 (25 tracks – Total Time: 69:27) Percy Grainger plays (Percy Grainger, piano) – includes: TOCCATA & FUGUE IN D MINOR (Bach); PRELUDE & FUGUE IN A MINOR (Bach); FANTASIA & FUGUE IN G MINOR (Bach); ICH RUF ZU DIR (Bach arr. Busoni); SONATA NO.2 IN G MINOR op. 22 (Schumann); ETUDE IN B MINOR op. 25/10 (Chopin); ETUDE IN C MINOR op. 25/12 (Chopin); WEDDING DAY AT TROLDHAUGEN (Grieg); POUR LE PIANO [Toccata only](Debussy) (Grainger talks on Pagodes, Estampes [Pagodes only]); GOLLIWOG'S CAKEWALK (Debussy); MOLLY ON THE SHORE. Pavilion Records PEARL GEMM CD 9957 (19 tracks – Total Time: 78:30) Percy Grainger plays – Volume II (Percy Grainger, piano) – includes: PIANO SONATA NO.2 IN B-FLAT MINOR op. 35 (Chopin); PIANO SONATA NO.1 IN B MINOR op. 58 (Chopin); ETUDES SYMPHONIQUES op. -

Percy Grainger and Ralph Vaughan Williams

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2009-01-01 Percy Grainger and Ralph Vaughan Williams: A Comparative Study of English Folk-Song Settings for Wind Band Shawna Meggan Holtz University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Folklore Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Holtz, Shawna Meggan, "Percy Grainger and Ralph Vaughan Williams: A Comparative Study of English Folk-Song Settings for Wind Band" (2009). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 2710. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/2710 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PERCY GRAINGER AND RALPH VAUGHAN WILLIAMS: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF ENGLISH FOLK-SONG SETTINGS FOR WIND BAND SHAWNA MEGGAN HOLTZ Department of Music APPROVED: _________________________________ Ron Hufstader, Ph. D., Chair ________________________________ David Ross, D.M.A. _________________________ Kim Bauer, M.F.A. ________________________ Patricia D. Witherspoon, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School Copyright © By Shawna Holtz 2009 To Joshua Coleman PERCY GRAINGER AND RALPH VAUGHAN WILLIAMS: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF ENGLISH FOLK-SONG SETTINGS FOR WIND BAND by SHAWNA MEGGAN HOLTZ, B.M.E. THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at El Paso in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC Department of Music THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO December 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF CONTENTS.……...………………………………………………………………..…v LIST OF FIGURES………………………………………………………………………………..vi CHAPTER I. -

Essential Excerpts for Tuba from Original Works Written for Wind Ensemble

HARVEY, BRENT MEADOWS, D.M.A. Essential Excerpts for Tuba from Original Works Written for Wind Ensemble. (2007) Directed by Dr. Dennis W. AsKew. 54 pp. The need for a standard course of study to assist in preparing students for military band auditions is apparent due to the current number of tuba positions in premier military service band organizations. This examination of Essential Excerpts for Tuba from Original Works Written for Wind Ensemble is intended to be an important document in the field of tuba performance and teaching for practice, preparation, and study of the original wind symphony literature written for tuba. The excerpts included in this text are selected based on a general survey created by the author. The Tuba Excerpt Survey, completed by retired and current premier military service band tuba players and select college and university tuba professors, generated a standard list of excerpts that produced the desired information that finalized the specified essential tuba excerpts to be included and reviewed in this document. By setting performance boundaries, inspecting the musical details of the excerpts, and separating an undergraduate curriculum into appropriate levels of study, a classification and distribution of the found scores and excerpts among different levels is established in this text. Upon examination of these excerpts, additional methodologies and corollary studies have been integrated into the paper to further facilitate student practice and preparation of these essential excerpts for tuba among original -

Piccolo in C Excerpt 1: Command March by Samuel Barber

Piccolo in C Excerpt 1: Command March by Samuel Barber Fast march-time ♩=144 4/4 time Excerpt 2: Lincolnshire Posy Mvnt. 4: The Brisk Young Sailor m 18-25 Sprightly 3/4 time Excerpt 3: Lincolnshire Posy Mvnt. 3: Rufford Park Poachers (Version A) M 1-10 Flowingly Flute Excerpt 1: Command March by Samuel Barber Fast march-time ♩=144 4/4 time Excerpt 2: Lincolnshire Posy Mvnt. 4: The Brisk Young Sailor m 18-25 Sprightly 3/4 time Excerpt 3: Lincolnshire Posy Mvnt. 2: Harkstow Grange m 10-20 Slowly Flowing Oboe Excerpt 1: Command March by Samuel Barber Fast march-time ♩=144 4/4 time Excerpt 2: Lincolnshire Posy Mvnt. 4: The Brisk Young Sailor m 25-33 Sprightly 3/4 time Excerpt 3: Lincolnshire Posy Mvnt. 2: Harkstow Grange m 10-20 Slowly Flowing Bassoon Excerpt 1: Command March by Samuel Barber Fast march-time ♩=144 4/4 time Excerpt 2: Lincolnshire Posy Mvnt. 4: The Brisk Young Sailor m 32-39 Sprightly 3/4 time Excerpt 3: Lincolnshire Posy Mvnt. 2: Harkstow Grange m 10-17 Slowly Flowing Bb Clarinet Excerpt 1: Command March by Samuel Barber Fast march-time ♩=144 4/4 time Excerpt 2: Lincolnshire Posy Mvnt. 4: The Brisk Young Sailor m 18-25 Sprightly 3/4 time Excerpt 3: Lincolnshire Posy Mvnt. 2: Harkstow Grange m 10-19 Slowly Flowing Bass Clarinet Excerpt 1: Command March by Samuel Barber Fast march-time ♩=144 4/4 time Excerpt 2: Lincolnshire Posy Mvnt. 4: The Brisk Young Sailor m 32-40 Sprightly 3/4 time Excerpt 3: Lincolnshire Posy Mvnt. -

WIND SYMPHONY Featuring Members of the Texas State Choirs

WIND SYMPHONY featuring members of the Texas State Choirs Caroline Beatty, conductor Chase Failing, graduate student conductor Evans Auditorium | Presented Online Monday November 23, 2020 | 7:30pm PROGRAM VARIATIONS ON "AMERICA" Charles Ives OF OUR NEW DAY BEGUN Omar Thomas LINCOLNSHIRE POSY Percy Grainger NOTES As we may be affected in numerous ways by the world-wide pandemic and local mitigations, we are more potently mindful of the privilege of performing music together and of the community created in joining with others in that endeavor. We are destined to listen, provide support, sing out, allow, take turns, and so much more - all while knowing we are singular parts to something bigger and more meaningful. We reflect upon those valuable features of ensemble music-making in the repertoire of this concert. It is through listening and hearing people’s stories we gain empathy and understanding and can further meaningful conversation to foster the beauty of compassion and gratitude. And through the sharing of song, stories, and anthems we give of ourselves and celebrate community. Variations on ‘America’ (1891) by Charles Ives began as this quintessentially quirky American composer’s contribution to pipe organ repertoire when a prodigious seventeen-year-old. The tune Ives manipulates in his variations is widely known in the United States as “America” or “My Country 'Tis of Thee” and functions as an unoff icial anthem. However, it has an even broader history of being used as catalyst for community as it is used for Britain’s “God Save The Queen” as well as for anthems in Norway, Germany, Russia, Switzerland, and Lichtenstein. -

An Introduction to Percy Grainger

CHANDOS :: intro CHAN 2029 an introduction to Percy Grainger :: 17 CCHANHAN 22029029 BBook.inddook.indd 116-176-17 330/7/060/7/06 113:26:393:26:39 Percy Grainger (1882–1961) 1 Country Gardens [BFMS Unnum.] 2:21 Version A Edited by Dana Paul Perna 2 Irish Tune from County Derry* 4:23 Classical music is inaccessible and diffi cult. It’s surprising how many people still believe 3 Green Bushes [BFMS No. 12] 8:30 the above statement to be true, so this new series from Chandos is not only welcome, it’s also very † necessary. 4 Early One Morning [BFMS Unnum.] 3:03 I was lucky enough to stumble upon the Stephen Varcoe baritone wonderful world of the classics when I was a David Archer trumpet • Andrew Watkinson violin child, and I’ve often contemplated how much poorer my life would have been had I not done 5 There Was a Pig Went Out to Dig so. As you have taken the fi rst step by buying this [BFMS No. 18]‡ 2:03 CD, I guarantee that you will share the delights of this epic journey of discovery. Each CD in the 6 Shepherd’s Hey [BFMS No. 16] 2:06 series features the orchestral music of a specifi c composer, with a selection of his ‘greatest hits’ 7 Shallow Brown [SCS No. 3]†‡ 6:12 CHANDOS played by top quality performers. It will give you Stephen Varcoe baritone a good fl avour of the composer’s style, but you won’t fi nd any nasty surprises – all the music is Lincolnshire Posy [BFMS No. -

Thomas Carl Slattery-The Wind Music of Percy Aldridge Grainger Ann Arbor: University Microfilms (UM Order No

Thomas Carl Slattery-The Wind Music of Percy Aldridge Grainger Ann Arbor: University Microfilms (UM order no. 67-9104, 1967. 265 pp., The University ofIowa diss.) David S. Josephson [Ed. Note,' This is the second in a series of writings conceived by Prof. Josephson as an essay in bibliography, seeking to provide the foundation for a thorough and broadly-based study of the life and music of Percy Grainger. The first essay, "Percy Grainger: Country Gardens and Other Curses," can be found in Current Musicology 15 (1973): 56-63.] Percy Grainger composed and arranged music for winds from virtually the beginning to the end of his creative life. The fruits of these labors are the subject, at first glance, of the dissertation under review. In fact, however, Thomas Slattery's thesis is more than a study of the wind music: in both scope and length it is the first major attempt to deal with Grainger's life and work. The wind music provides an apt vehicle, for its remarkable range of idiom, genre, and intention allows us to explore the gamut of Grainger's productive life from almost every angle; the finest exemplars of this repertory reveal most immediately his striking ear and fastidious craftsmanship. In- deed, Grainger's largest essay for winds, Lincolnshire Posy, is a handbook of band orchestration and arguably the most idiomatic and sensitive composi- tion ever written for large wind ensemble. The table of contents reveals both the scale of Dr. Slattery's investigation and its cogent organization. The six chapters include an extended biblio- graphical summary; music for wind band; the chamber music for, with, and arranged for winds; Grainger's wind scoring; his innovations; and a sum- mary of sources. -

Wind Ensemble

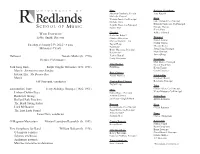

Flute Baritone Saxophone Shannon Canchola, Piccolo Troy Rausch Michelle Chavez* Victoria Jones, Co-Principal Horn Nichole Hans Luke Hilland, Co-Principal Jennifer Yoon, Co-Principal Eduardo Contreras, Co-Principal Sophie Wu* Enrique Macias Kerrie Pitts Clarinet Ashley Schmidt IND NSEMBLE W E Katherine Baber* Eddie Smith, Director Candice Broersma Trumpet Michael Garman – Eb Daniel Adams Caitlin Curran Tuesday, February 14th, 2012 - 8 p.m. Taylor Heap Paul Kane Sheena Dreher MEMORIAL CHAPEL Britni Marinaro, Principal Jason Nam, Principal Kay Nevin* Mark Omiliak James Sharp Hallower Natalie Moller (b. 1990) Jessica Nunez* Emily Praetorius Premier Performance Trombone Matt Shaver, Principal Alto Clarinet Steven Stockman Folk Song Suite Ralph Vaughn Williams (1872-1958) Paul Kane Kevin Throne March: Seventeen come Sunday Gavin Thrasher Bass Clarinet Intermezzo: My Bonnie Boy Amara Markley Euphonium March Elizabeth Dowty Jeff Osarczuk, conductor Contra-Bass Clarinet Ben Solis, Principal Taylor Heap Tuba Curtiss Allen, Co-Principal Lincolnshire Posy Percy Aldridge Grainger (1882-1961) Oboe Victor Mortson, Co-Principal Lisbon (Dublin Bay) Nancy Blaire, Principal Horkstow Grange Andrew Valencia String Bass Rufford Park Poachers Ian Sharp – English Horn Alyssa Adamson The Brisk Young Sailor Bassoon Harp Lord Melbourne Kevin Eberle, Co-Principal Cheryl Rotundo The Lost Lady Found Jason Davis, Co-Principal Jason Nam, conductor Anna Garmin* Piano Simona Sires Michael Malakouti O Magnum Mysterium Morten Lauridsen/Reynolds (b. 1943) Contra Bassoon -

California State University, Northridge

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE A STUDY OF FOLK SONGS IN THE WIND BAND REPERTOIRE: A CONDUCTOR AND EDUCATOR’S POINT OF VIEW A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Music in Music, Conducting By Claudio D. Alcántar May 2018 The thesis of Claudio D. Alcántar is approved: _________________________________________ ____________ Prof. Mary Schliff Date _________________________________________ ____________ Prof. Gary Pratt Date _________________________________________ ____________ Dr. Lawrence Stoffel, Chair Date California State University, Northridge ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my immense gratitude to Dr. Lawrence Stoffel for being an amazing human being and for guiding and inspiring me to pursue a career in music education. Your love for music making and your dedication and support for music education has truly inspired me. I am forever thankful for your support and mentorship over these last two years. Gary Pratt, your love and dedication to Cal State Northridge, its students and the community continues to amaze me. Thank you for being a great role model and bringing out the best out of every student over your career as a musician and educator. You have truly inspired me to follow your steps. Mary Schliff, thank you for your continuous help over these years. You keep the music education and credential program going at Cal State Northridge and I thank you for your dedication and hard work. You have created many music educators and continue to encourage me to get out there and teach! iii DEDICATION Dedicated to my family, friends, students, teachers and everyone that has played a role in my development and growth as a musician, educator, conductor and human being. -

PROGRAM NOTES June 4 2021 Final

Classical Series Friday, June 4, 2021 at 1:30 p.m. and 8:00 p.m. Saturday, June 5, 2021 at 1:30 p.m. and 8:00 p.m. Sunday, June 6, 2021 at 2:00 p.m. and 7:00 p.m. Helzberg Hall, Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts Michael Stern, conductor WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART Serenade No. 11 in E-flat Major, K. 375 I. Allegro maestoso II. Menuetto I III. Adagio IV. Menuetto II V. Allegro PAUL DUKAS Fanfare to Precede La Péri TIMOTHY HIGGINS Sinfonietta I. Introit II. Arias III. Scherzo IV. Finale PERCY ALDRIDGE GRAINGER Lincolnshire Posy (arr. Higgins) I. “Lisbon” II. “Horkstow Grange” III. “Rufford Park Poachers” IV. “The Brisk Young Sailor” V. “Lord Melbourne” VI. “The Lost Lady Found” The 2020/21 Season is generously sponsored by The Classical Series is sponsored by SHIRLEY AND BARNETT C. HELZBERG, JR. Additional support provided by R. CROSBY KEMPER JR. FUND Classical Series Program Notes June 4-6, 2021 Orchestra Roster MICHAEL STERN, Music Director JASON SEBER, David T. Beals III Associate Conductor FIRST VIOLINS John Eadie HORNS Sunho Kim, Acting Concertmaster Lawrence Figg Alberto Suarez, Principal Miller Nichols Chair Rung Lee* Landon and Sarah Rowland Chair Stirling Trent, Meredith McCook David Sullivan, Associate Principal Acting Associate Concertmaster Allen Probus Elizabeth Gray Chiafei Lin, David Gamble Acting Assistant Concertmaster DOUBLE BASSES Stephen Multer, Gregory Sandomirsky ‡, Jeffrey Kail, Principal Associate Principal Emeritus Associate Concertmaster Emeritus Evan Halloin, Associate Principal Anne-Marie Brown Brandon Mason ‡ TRUMPETS Betty Chen Caleb Quillen Julian Kaplan, Principal Anthony DeMarco Richard Ryan James B.