Grainger and the Intimate Saxophone/2020/Final Final.Pages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lincolnshire Posy

CONDUCTOR 04005975 Two Movements from LINCOLNSHIRE POSY PERCY ALDRIDGE GRAINGER Arranged by MICHAEL SWEENEY INSTRUMENTATION 1 - Full Score 8 - Flute Part 1 2 - Oboe 6 - B% Clarinet/B% Trumpet 4 - Violin 6 - B% Clarinet/B% Trumpet Part 2 2 - E% Alto Saxophone 4 - Violin 4 - B% Clarinet 2 - B% Tenor Saxophone % % Part 3 2 - E Alto Saxophone/E Alto Clarinet 2 - F Horn 2 - Violin 4 - Viola 4 - B% Tenor Saxophone/Baritone T.C. 2 - F Horn Part 4 4 - Trombone/Baritone B.C./Bassoon 2 - Cello 2 - B% Bass Clarinet 4 - Trombone/Baritone B.C./Bassoon 2 - Baritone T.C. Part 5 2 - Cello 2 - E% Baritone Saxophone 4 - Tuba 2 - String/Electric Bass 2 - Percussion 1 Snare Drum, Bass Drum 2 - Percussion 2 Sus. Cym. 2 - Mallet Percussion Bells, Xylophone, Chimes, Crotales 1 - Timpani Additional Parts U.S. $2.50 Score (04005975) U.S. $7.50 8 88680 94789 7 HAL LEONARD Two Movements from FLEX-BAND SERIES LINCOLNSHIRE POSY PERCY ALDRIDGE GRAINGER Duration – 2:15 (Œ = 72-76) Arranged by MICHAEL SWEENEY Slowly flowingly Horkstow Grange 5 PART 1 Cl. preferred bb 4 a2 œ œ œ œ 5 œ. œ œ œ 4 œ œ œ œ 5 œ œ ˙œœ 4 œ œ œ œ œ œ œ Flute/Oboe & 4 œ œ 4 ˙ 4 œ 4 4 œ œ P F P F 4 a2 5 4 5 4 B¯ Clarinet/ & 4 4 œ. œ 4 4 œ œ 4 œ œ B¯ Trumpet œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙œœ œ œ œ œ œ œ Pœ ˙ F P F œ ≤ ≥ ≤ ≥ ≥ bb 4 5 4 5 4 Violin & 4 œ 4 œ. -

New Century Saxophone Quartet Press

New Century Saxophone Quartet Press KALAMAZOO GAZETTE Thursday, July 12, 2007 Saxophone ensemble shows off versatility By C.J. Gianakaris uesday in South Haven and Precise, synchronized playing Wednesday night at Brook Lodge T in Augusta, Fontana Chamber Arts was matched by a balanced presented the New Century blend … A total winner. Saxophone Quartet. Its playing of a wide range of works, by seven different By the last half of the concert, it composers, initiated the audience in the became clear that certain compositions musical possibilities of such ensembles. lend themselves more to saxophone sound The New Century features Michael than others. The first section of Astor Stephenson on soprano saxophone, Chris- Piazzolla’s marvelous “Histoire du topher Hemingway on alto saxophone, Tango,” arranged by Claude Voirpy, was Stephen Pollock on tenor saxophone and a total winner. Infectious tango rhythms Connie Frigo on baritone saxophone. worked well for saxes, as did tapping of After marching in while playing Bob the instrument’s body — a technique Mintzer’s invigorating “Contraption,” the heard often in Piazzolla’s music. ensemble turned to five selections from George Gershwin’s great American J.S. Bach’s “Art of the Fugue,” BMV opera “Porgy and Bess” also sounded 1080. Immediately impressive was the especially fine. Our ears are accustomed velvety aura emanating from different to hearing Gershwin played with soaring saxophones possessing varying ranges. reed instruments, clarinet or sax, Precise, synchronized playing was deliberately scored. So the sounds were matched by a balanced blend, suggesting warm and familiar. saxophones could present Bach’s works as well as other instruments. -

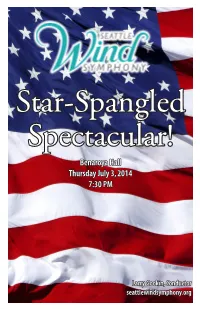

2014 SSS Program.Indd

Star-Spangled Spectacular! Benaroya Hall Thursday July 3, 2014 7:30 PM Larry Gookin, Conductor seattlewindsymphony.org Program The Star-Spangled Banner ................... Orchestrated by John Philip Sousa Harmonized by Walter Damrosch / Arranged by Keith Brion America The Beautiful........................... Samuel Augustus Ward / Arranged by Carmen Dragon ~Welcome~ Liberty Bell March ................................ Orchestrated by John Philip Sousa Arranged by Keith Brion Seattle Wind Symphony is especially proud to present our second STAR SPANGLED SPECTACULAR musical salute Thoughts of Love .................................. Arthur Pryor to our nation. Our music for this “extravaganza” has been selected to put a song on your lips, tears in your eyes Matthew Grey, Trombone Soloist and a warm feeling of patriotism in your heart. We want to extend a special welcome and thanks to the Honor Oh Shenandoah ................................... Arranged by Frank Ticheli Guard from Joint Base Lewis McChord for presenting the colors to start our concert. We also want to thank the management of Benaroya Hall for their excellent leadership in our presentation today. We are very appreciative of Through The Air .................................... August Damm the participation of vocal soloist Sheila Houlahan and our narrator Dave Beck for sharing their talents, and for our Sara Jolivet, Piccolo Soloist instrumental soloists Michel Jolivet, Sara Jolivet, and Matt Grey. Thank You! Marching Through Georgia ................... John Philip Sousa Arranged by Keith Brion With today’s concert, Seattle Wind Symphony will have completed our third season. We recognize that most Rolling Thunder .................................... Henry Fillmore people have never heard high quality symphonic wind music, so we would like to invite you to our regular season performances. The 2014-2015 season dates are posted on our web site: www.seattlewindsymphony.org. -

WOODWIND INSTRUMENT 2,151,337 a 3/1939 Selmer 2,501,388 a * 3/1950 Holland

United States Patent This PDF file contains a digital copy of a United States patent that relates to the Native American Flute. It is part of a collection of Native American Flute resources available at the web site http://www.Flutopedia.com/. As part of the Flutopedia effort, extensive metadata information has been encoded into this file (see File/Properties for title, author, citation, right management, etc.). You can use text search on this document, based on the OCR facility in Adobe Acrobat 9 Pro. Also, all fonts have been embedded, so this file should display identically on various systems. Based on our best efforts, we believe that providing this material from Flutopedia.com to users in the United States does not violate any legal rights. However, please do not assume that it is legal to use this material outside the United States or for any use other than for your own personal use for research and self-enrichment. Also, we cannot offer guidance as to whether any specific use of any particular material is allowed. If you have any questions about this document or issues with its distribution, please visit http://www.Flutopedia.com/, which has information on how to contact us. Contributing Source: United States Patent and Trademark Office - http://www.uspto.gov/ Digitizing Sponsor: Patent Fetcher - http://www.PatentFetcher.com/ Digitized by: Stroke of Color, Inc. Document downloaded: December 5, 2009 Updated: May 31, 2010 by Clint Goss [[email protected]] 111111 1111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 US007563970B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,563,970 B2 Laukat et al. -

Faculty Recital, Ronald L. Caravan, Clarinet, Soprano Saxophone, Alto Saxophone, Assisted by Sar Shalom Strong, Piano

Syracuse University SURFACE Setnor School of Music - Performance Programs Setnor School of Music 2-24-2008 Faculty Recital, Ronald L. Caravan, Clarinet, soprano Saxophone, Alto Saxophone, Assisted by Sar Shalom Strong, Piano Ronald L. Caravan Syracuse University Sar Shalom Strong Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/setnor_performances Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Setnor School of Music, Syracuse University. Faculty Recital, Ronald L. Caravan, Clarinet, soprano Saxophone, Alto Saxophone, Assisted by Sar Shalom Strong, Piano. 2-24-2008 https://surface.syr.edu/ setnor_performances/7 This Performance Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Setnor School of Music at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Setnor School of Music - Performance Programs by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY SETNOR SCHOOL OF MUSIC Faculty Recital Ronald L. Caravan Clarinet, Soprano Saxophone, Alto Saxophone Assisted by Sar Shalom Strong Piano SETNOR AUDITORIUM SUNDAY, FEB. 24, 2008 2:00 P.M. Program Rondo Capriccioso . Anton Stamitz adapted for C clarinet & piano by Ronald Caravan (1750-c.1809) Soliloquy & Scherzo (2000) ........ ................ Walters. Hartley for Eb clarinet & piano Four Episodes (2006) ................................ Fred Cohen for Bb clarinet & piano 1. Flash 2. Breath 3. Arioso 4. Pure -Intermission - Sonata (1969) .............................. ..... Erwin Chandler for alto saxophone & piano 1. Allegro 2. Con moto 3. With drive Sonata (1976) . ... ............................. Brian Bevelander for alto saxophone & piano (in one movement) Soliloquy & Celebration (1996) ................... Ronald L. Caravan A tribute to the classic jazz saxophonist Paul Desmond for soprano saxophone & piano About the Performers .. -

Spectralism in the Saxophone Repertoire: an Overview and Performance Guide

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY Spectralism in the Saxophone Repertoire: An Overview and Performance Guide A PROJECT DOCUMENT SUBMITTED TO THE BIENEN SCHOOL OF MUSIC IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS for the degree DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS Program of Saxophone Performance By Thomas Michael Snydacker EVANSTON, ILLINOIS JUNE 2019 2 ABSTRACT Spectralism in the Saxophone Repertoire: An Overview and Performance Guide Thomas Snydacker The saxophone has long been an instrument at the forefront of new music. Since its invention, supporters of the saxophone have tirelessly pushed to create a repertoire, which has resulted today in an impressive body of work for the yet relatively new instrument. The saxophone has found itself on the cutting edge of new concert music for practically its entire existence, with composers attracted both to its vast array of tonal colors and technical capabilities, as well as the surplus of performers eager to adopt new repertoire. Since the 1970s, one of the most eminent and consequential styles of contemporary music composition has been spectralism. The saxophone, predictably, has benefited tremendously, with repertoire from Gérard Grisey and other founders of the spectral movement, as well as their students and successors. Spectral music has continued to evolve and to influence many compositions into the early stages of the twenty-first century, and the saxophone, ever riding the crest of the wave of new music, has continued to expand its body of repertoire thanks in part to the influence of the spectralists. The current study is a guide for modern saxophonists and pedagogues interested in acquainting themselves with the saxophone music of the spectralists. -

Yamaha 2018 Price List

two thousand eighte2en 01 8 accessories retail price lis t effective date: July 1, 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS BRASSWIND MOUTHPIECES 1-4 REEDS 17-21 TRUMPET 1 SOPRANO CLARINET 17 CORNET, SHORT SHANK 2 CLARINET 17 CORNET, LONG SHANK 2 ALTO CLARINET 17 FLUGELHORN 2 BASS CLARINET 18 ALTO 2 CONTRA CLARINET 18 HORN 2-3 SOPRANINO SAXOPHONE 18 MELLOPHONE 3 SOPRANO SAXOPHONE 18 TROMBONE, SMALL SHANK TENOR 3 ALTO SAXOPHONE 19 TROMBONE, LARGE SHANK TENOR 3 TENOR SAXOPHONE 19-20 BASS TROMBONE 4 BARITONE SAXOPHONE 20 EUPHONIUM 4 BASS SAXOPHONE 20 TUBA 4 DOUBLE REEDS 20-21 SILENT BRASS ™ & MUTES 5-6 WOODWIND ACCESSORIES 22-30 SILENT BRASS SYSTEMS 5 LIGATURES 21-23 SILENT BRASS MUTES 5 MOUTHPIECE CAPS 24-25 TRADITIONAL MUTES 5-6 NECKSTRAPS 25-26 INSTRUMENT OILS & LUBRICANTS 26 BRASSWIND ACCESSORIES 7-9 MAINTENANCE KITS 26 BRASS INSTRUMENT OILS & LUBRICANTS 7 POLISHES & POLISHING CLOTHS 27 BRASS INSTRUMENT MAINTENANCE KIT 7 CLEANING SWABS 27 POLISHES & POLISHING CLOTHS 7 MAINTENANCE SUPPLIES 27-28 BRASS INSTRUMENT BRUSHES & CLEANING TOOLS 8 LIP PLATE & MOUTHPIECE PATCHES 28 PREMIUM MICROFIBER BRASS SWABS 8 REED TRIMMERS & SHAPERS 29 MISCELLANEOUS BRASS INSTRUMENT ACCESSORIES 9 REED CASES & STORAGE 29 BRASS INSTRUMENT LYRES 9 MISCELLANEOUS WOODWIND ACCESSORIES 29 INSTRUMENT LYRES 30 BRASSWIND CASES 10 WOODWIND CASES 31 WOODWIND MOUTHPIECES 11-16 PICCOLO CLARINET 11 RECORDERS & PIANICAS 32-33 SOPRANO CLARINET 11 PIANICAS 32 CLARINET 11-12 20 SERIES PLASTIC RECORDERS 32 ALTO CLARINET 12 300 SERIES PLASTIC RECORDERS 32 BASS CLARINET 12 400 SERIES PLANT-BASED -

The Composer's Guide to the Tuba

THE COMPOSER’S GUIDE TO THE TUBA: CREATING A NEW RESOURCE ON THE CAPABILITIES OF THE TUBA FAMILY Aaron Michael Hynds A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS August 2019 Committee: David Saltzman, Advisor Marco Nardone Graduate Faculty Representative Mikel Kuehn Andrew Pelletier © 2019 Aaron Michael Hynds All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT David Saltzman, Advisor The solo repertoire of the tuba and euphonium has grown exponentially since the middle of the 20th century, due in large part to the pioneering work of several artist-performers on those instruments. These performers sought out and collaborated directly with composers, helping to produce works that sensibly and musically used the tuba and euphonium. However, not every composer who wishes to write for the tuba and euphonium has access to world-class tubists and euphonists, and the body of available literature concerning the capabilities of the tuba family is both small in number and lacking in comprehensiveness. This document seeks to remedy this situation by producing a comprehensive and accessible guide on the capabilities of the tuba family. An analysis of the currently-available materials concerning the tuba family will give direction on the structure and content of this new guide, as will the dissemination of a survey to the North American composition community. The end result, the Composer’s Guide to the Tuba, is a practical, accessible, and composer-centric guide to the modern capabilities of the tuba family of instruments. iv To Sara and Dad, who both kept me going with their never-ending love. -

Molly on the Shore for Clarinet Quartet Sheet Music

Molly On The Shore For Clarinet Quartet Sheet Music Download molly on the shore for clarinet quartet sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 6 pages partial preview of molly on the shore for clarinet quartet sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 3576 times and last read at 2021-09-27 19:50:51. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of molly on the shore for clarinet quartet you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Bass Clarinet, E Flat Clarinet Ensemble: Clarinet Quartet, Woodwind Quartet Level: Advanced [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Molly On The Shore Clarinet Quartet Molly On The Shore Clarinet Quartet sheet music has been read 5226 times. Molly on the shore clarinet quartet arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-28 22:37:37. [ Read More ] Molly On The Shore 2 Clarinets Molly On The Shore 2 Clarinets sheet music has been read 3367 times. Molly on the shore 2 clarinets arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-28 15:25:49. [ Read More ] Molly On The Shore Irish Folk Clarinet Choir Octet Molly On The Shore Irish Folk Clarinet Choir Octet sheet music has been read 3708 times. Molly on the shore irish folk clarinet choir octet arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-25 18:29:55. -

Lincolnshire Posy Abbig

A Historical and Analytical Research on the Development of Percy Grainger’s Wind Ensemble Masterpiece: Lincolnshire Posy Abbigail Ramsey Stephen F. Austin State University, Department of Music Graduate Research Conference 2021 Dr. David Campo, Advisor April 13, 2021 Ramsey 1 Introduction Percy Grainger’s Lincolnshire Posy has become a staple of wind ensemble repertoire and is a work most professional wind ensembles have performed. Lincolnshire Posy was composed in 1937, during a time when the wind band repertoire was not as developed as other performance media. During his travels to Lincolnshire, England during the early 20th century, Grainger became intrigued by the musical culture and was inspired to musically portray the unique qualities of the locals that shared their narrative ballads through song. While Grainger’s collection efforts occurred in the early 1900s, Lincolnshire Posy did not come to fruition until it was commissioned by the American Bandmasters Association for their 1937 convention. Grainger’s later relationship with Frederick Fennell and Fennell’s subsequent creation of the Eastman Wind Ensemble in 1952 led to the increased popularity of Lincolnshire Posy. The unique instrumentation and unprecedented performance ability of the group allowed a larger audience access to this masterwork. Fennell and his ensemble’s new approach to wind band performance allowed complex literature like Lincolnshire Posy to be properly performed and contributed to establishing wind band as a respected performance medium within the greater musical community. Percy Grainger: Biography Percy Aldridge Grainger was an Australian-born composer, pianist, ethnomusicologist, and concert band saxophone virtuoso born on July 8, 1882 in Brighton, Victoria, Australia and died February 20, 1961 in White Plains, New York.1 Grainger was the only child of John Harry Grainger, a successful traveling architect, and Rose Annie Grainger, a self-taught pianist. -

A Performance Project For

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Summer 8-2007 A PERFORMANCE PROJECT FOR SAXOPHONE ORCHESTRA ONC SISTING OF FIVE PERFORMANCE EDITIONS FROM THE RENAISSANCE, BAROQUE, CLASSICAL, ROMANTIC, AND MODERN ERAS Marcus Daniel Ballard University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Composition Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Ballard, Marcus Daniel, "A PERFORMANCE PROJECT FOR SAXOPHONE ORCHESTRA ONC SISTING OF FIVE PERFORMANCE EDITIONS FROM THE RENAISSANCE, BAROQUE, CLASSICAL, ROMANTIC, AND MODERN ERAS" (2007). Dissertations. 1228. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1228 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi A PERFORMANCE PROJECT FOR SAXOPHONE ORCHESTRA CONSISTING OF FIVE PERFORMANCE EDITIONS FROM THE RENAISSANCE, BAROQUE, CLASSICAL, ROMANTIC, AND MODERN ERAS by Marcus Daniel Ballard A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Studies Office of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Approved: August 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. COPYRIGHT BY MARCUS DANIEL BALLARD 2007 Reproduced -

Discography Percy Grainger Compiled by Barry Peter Ould Mainly Piano

Discography Percy Grainger compiled by Barry Peter Ould mainly piano Percy Grainger (Percy Grainger, piano) – includes: PRELUDE AND FUGUE IN A MINOR (Bach); TOCCATA AND FUGUE IN D MINOR (Bach); FANTASY AND FUGUE IN G MINOR (Bach); SONATA NO.2 IN B-FLAT MINOR op. 35 (Chopin); ETUDE IN B MINOR op. 25/10 (Chopin); SONATA NO.3 IN B MINOR op. 58 (Chopin). Biddulph Recordings LHW 010 (12 tracks – Total Time: 76:08) Percy Grainger (Percy Grainger, piano) – includes: SONATA NO.2 IN G MINOR op.22 (Schumann); ROMANCE IN F-SHARP op. 28/2 (Schumann); WARUM? (from op. 12) (Schumann); ETUDES SYMPHONIQUES (op. 13) (Schumann); WALTZ IN A-FLAT op. 39/15 (Brahms); SONATA NO.3 IN F MINOR op. 5 (Brahms). Biddulph Recordings LHW 008 (25 tracks – Total Time: 69:27) Percy Grainger plays (Percy Grainger, piano) – includes: TOCCATA & FUGUE IN D MINOR (Bach); PRELUDE & FUGUE IN A MINOR (Bach); FANTASIA & FUGUE IN G MINOR (Bach); ICH RUF ZU DIR (Bach arr. Busoni); SONATA NO.2 IN G MINOR op. 22 (Schumann); ETUDE IN B MINOR op. 25/10 (Chopin); ETUDE IN C MINOR op. 25/12 (Chopin); WEDDING DAY AT TROLDHAUGEN (Grieg); POUR LE PIANO [Toccata only](Debussy) (Grainger talks on Pagodes, Estampes [Pagodes only]); GOLLIWOG'S CAKEWALK (Debussy); MOLLY ON THE SHORE. Pavilion Records PEARL GEMM CD 9957 (19 tracks – Total Time: 78:30) Percy Grainger plays – Volume II (Percy Grainger, piano) – includes: PIANO SONATA NO.2 IN B-FLAT MINOR op. 35 (Chopin); PIANO SONATA NO.1 IN B MINOR op. 58 (Chopin); ETUDES SYMPHONIQUES op.