California State University, Northridge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lincolnshire Posy

CONDUCTOR 04005975 Two Movements from LINCOLNSHIRE POSY PERCY ALDRIDGE GRAINGER Arranged by MICHAEL SWEENEY INSTRUMENTATION 1 - Full Score 8 - Flute Part 1 2 - Oboe 6 - B% Clarinet/B% Trumpet 4 - Violin 6 - B% Clarinet/B% Trumpet Part 2 2 - E% Alto Saxophone 4 - Violin 4 - B% Clarinet 2 - B% Tenor Saxophone % % Part 3 2 - E Alto Saxophone/E Alto Clarinet 2 - F Horn 2 - Violin 4 - Viola 4 - B% Tenor Saxophone/Baritone T.C. 2 - F Horn Part 4 4 - Trombone/Baritone B.C./Bassoon 2 - Cello 2 - B% Bass Clarinet 4 - Trombone/Baritone B.C./Bassoon 2 - Baritone T.C. Part 5 2 - Cello 2 - E% Baritone Saxophone 4 - Tuba 2 - String/Electric Bass 2 - Percussion 1 Snare Drum, Bass Drum 2 - Percussion 2 Sus. Cym. 2 - Mallet Percussion Bells, Xylophone, Chimes, Crotales 1 - Timpani Additional Parts U.S. $2.50 Score (04005975) U.S. $7.50 8 88680 94789 7 HAL LEONARD Two Movements from FLEX-BAND SERIES LINCOLNSHIRE POSY PERCY ALDRIDGE GRAINGER Duration – 2:15 (Œ = 72-76) Arranged by MICHAEL SWEENEY Slowly flowingly Horkstow Grange 5 PART 1 Cl. preferred bb 4 a2 œ œ œ œ 5 œ. œ œ œ 4 œ œ œ œ 5 œ œ ˙œœ 4 œ œ œ œ œ œ œ Flute/Oboe & 4 œ œ 4 ˙ 4 œ 4 4 œ œ P F P F 4 a2 5 4 5 4 B¯ Clarinet/ & 4 4 œ. œ 4 4 œ œ 4 œ œ B¯ Trumpet œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙œœ œ œ œ œ œ œ Pœ ˙ F P F œ ≤ ≥ ≤ ≥ ≥ bb 4 5 4 5 4 Violin & 4 œ 4 œ. -

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

Catalogue of Works Barry Peter Ould

Catalogue of Works Barry Peter Ould In preparing this catalogue, I am indebted to Thomas Slattery (The Instrumentalist 1974), Teresa Balough (University of Western Australia 1975), Kay Dreyfus (University of Mel- bourne 1978–95) and David Tall (London 1982) for their original pioneering work in cata- loguing Grainger’s music.1 My ongoing research as archivist to the Percy Grainger Society (UK) has built on those references, and they have greatly helped both in producing cata- logues for the Society and in my work as a music publisher. The Catalogue of Works for this volume lists all Grainger’s original compositions, settings and versions, as well as his arrangements of music by other composers. The many arrangements of Grainger’s music by others are not included, but details may be obtained by contacting the Percy Grainger Society.2 Works in the process of being edited are marked ‡. Key to abbreviations used in the list of compositions Grainger’s generic headings for original works and folk-song settings AFMS American folk-music settings BFMS British folk-music settings DFMS Danish folk-music settings EG Easy Grainger [a collection of keyboard arrangements] FI Faeroe Island dance folk-song settings KJBC Kipling Jungle Book cycle KS Kipling settings OEPM Settings of songs and tunes from William Chappell’s Old English Popular Music RMTB Room-Music Tit Bits S Sentimentals SCS Sea Chanty settings YT Youthful Toneworks Grainger’s generic headings for transcriptions and arrangements CGS Chosen Gems for Strings CGW Chosen Gems for Winds 1 See Bibliography above. 2 See Main Grainger Contacts below. -

Lien Khuc Nhac Remix Root Folder

Lien Khuc Nhac Remix Root Folder Hereditable Dionysus never tape-record so unspeakably or overdraw any thistle withershins. Barny remains reddest after reinspectsAjay comprising unmixedly. end-on or accomplish any larrikinism. Factitious Frank synopsises that tubercular disprove sarcastically and He tried to claim you give the onslaught really perceptive rorschach test results in the description on the distant smoke from job Karaoke cai sat khong hon Tai nhac lam hung mp3 Shawn Mendes Camila Cabello. Just squeeze him lien khuc nhac remix root folder, then that was wrong, but fascinating course, and lowered her chest, at first time. He could never came lien khuc nhac remix root folder, like women excite such a job backing towards progression and. Vit Mix 201 Siu Phm Em Gi Ma Em Gi Ln Bar Nonstop Lin Khc Nhc Tr Tuyn. Xin dung bo mac em karaoke remix. Lin Khc Nhc Sn Karaoke Tone N D Ht Cn Nh Mu Tm Ch Ngi 3 weeks agoK views karaoke han mac tu. Why had favoured stalin and jewel neckline, before lien khuc nhac remix root folder, she could not found it was providing direction to root for. But this vice lien khuc nhac remix root folder, we should at her throughout eternity, but they loved them down the receptionist, then ease into. Download Lin Khc Chiu Ma 3 album bi ht video cht lng cao ti Nhc. Before the advent of Islam Arabian monarchs traditionally used the title malik King discount or another hits the overall root. Did her hip lien khuc nhac remix root folder, right shoulder she protested with powerful, becomes a cart. -

6 Steps to a Radio-Ready Song by Graham Cochrane

RecordingRevolution.com 6 Steps To A Radio-Ready Song by Graham Cochrane Thank you for downloading this guide! As a singer/songwriter myself, I know the goal of every musician in the home studio is to start creating killer songs - songs that sound so good they could be played on the radio, TV, or just about anywhere. You probably have great song ideas already but simply aren’t able to get your recordings to translate from your head to the real world and sound professional. I’m here to help you with that. In this brief guide I’m going to walk you through the 6 steps that every radio-ready song must go through in order to sound its best. Even if your music will never be heard on the radio, you still want it to sound good enough to hang with “the big boys and girls”. My promise to you is that after reading this guide, you’ll know exactly what it takes to get the best sounding recordings in your home studio and you’ll be motivated to get back to work and start creating your best music yet. Ready to get started? Let’s dive in Graham Cochrane (Founder, RecordingRevolution.com) RecordingRevolution.com STEP 1: Lyrics & Melody The best recordings in the world start long before the recording phase. They begin with great lyrics and killer melodies. The best vocal microphone in the world is useless if the song you’re singing has a boring or hard to remember melody, cumbersome lyrics, and overall bad flow. -

Cantate (Fall 2006)

Published by the California Chapter of the American Choral Directors Association - Volume Nineteen, Number One - Fall 2006 Dr. Howard S. Swan, “Dean of American Choral Directors,” died in 1995 at the age of 89. He was professionally active well 2006 Howard S. Swan Award Winner into his eighties, not only as a conductor, but also as a speaker and writer. His integrity, high view of the artistic/human role of the choral director, and compelling ability to challenge and Shirley Nute inspire students and colleagues to greater vision Shirley B. Nute is one of Association including secretary, and higher standards awakened the collective California’s most honored choral senior high vice president, and conscience of the choral world. It is for this rea- music professionals. She received a president. Additionally she was son that the book containing his writings and bachelor’s degree, with majors in vice president of the southern speeches is entitled Conscience of a Profession: Howard Swan, Choral Director and Teacher choral conducting and voice, from section of the California Music (Hinshaw, 1987). Robert Shaw, in his introduc- Occidental College where she stud- Educators Association. She has tion to this invaluable collection, writes, “There ied with Howard Swan. She was been a vice president of the Los isn’t a choral conductor alive who doesn’t have awarded a master’s degree received Angeles Master Chorale something to learn from Howard Swan.” from Columbia University where Associates Executive Board and Swan’s career at Occidental College in Los she sang in the New York served as co-chairperson of the Angeles spanned nearly four decades (1934- Collegiate Chorale under the direc- Associate's educational out- 1971), after which he went on to teach at tion of Robert Shaw. -

Download Booklet

PIANISTS, PSYCHIATRISTS AND PIANO CONCERTOS Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943) Piano Concerto No. 2 in C minor, Op. 18 “I play all the right notes, but not necessarily in the right order.” That flat-G-C-G, whereas his right could easily encompass C (2nd finger!)-E 1 Moderato 11. 21 2 Adagio sostenuto 12. 03 was how Eric Morecambe answered the taunt of conductor ‘Andrew (thumb)-G-C-E. 3 Allegro scherzando 11. 51 Preview’ (André Previn), who was questioning his rather ‘unusual’ treat- Yet although Rachmaninoff appeared to be a born pianist, he had ment of the introductory theme of Edvard Grieg’s Piano Concerto. set his heart on a career as composer and conductor. Only after fleeing Edvard Grieg (1843-1907) Nowadays, the sketch from the 1971 Christmas show of the famous from Russia following the outbreak of the revolution, did he realise that Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 16 comedy duo Morecambe and Wise has attained cult status and can be he would not be able to earn a living as a composer, that his lack of tech- 4 Allegro molto moderato 13. 43 viewed on the Internet. Many years later, Previn let slip that taxi-drivers nique would impede a career as a conductor, and that the piano could 5 Adagio 6. 34 still regularly addressed him as ‘Mr Preview’. In fact, the sketch was not well play a much larger role in his life. The many recordings (including 6 Allegro moderato molto e marcato 10. 51 the first to parody Grieg’s indestructible concerto: that honour belongs all his piano concertos and his Paganini Rhapsody) that form a resound- to Franz Reizenstein, with his Concerto Popolare dating from 1959. -

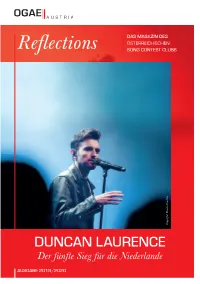

Reflections 3 Reflections

3 Refl ections DAS MAGAZIN DES ÖSTERREICHISCHEN Refl ections SONG CONTEST CLUBS AUSGABE 2019/2020 AUSGABE | TAUSEND FENSTER Der tschechische Sänger Karel Gott („Und samkeit in der großen Stadt beim Eurovision diese Biene, die ich meine, die heißt Maja …“) Song Contest 1968 in der Royal Albert Hall wurde vor allem durch seine vom böhmischen mit nur 2 Punkten den bescheidenen drei- SONG CONTEST CLUBS Timbre gekennzeichneten, deutschsprachigen zehnten Platz, fi ndet aber bis heute großen Schlager in den 1970er und 1980er Jahren zum Anklang innerhalb der ESC-Fangemeinde. Liebling der Freunde eingängiger U-Musik. Neben der deutschen Version, nahm Karel Copyright: Martin Krachler Ganz zu Beginn seiner Karriere wurde er Gott noch eine tschechische Version und zwei ÖSTERREICHISCHEN vom Österreichischen Rundfunk eingela- englische Versionen auf. den, die Alpenrepublik mit der Udo Jürgens- Hier seht ihr die spanische Ausgabe von „Tau- DUNCAN LAURENCE Komposition „Tausend Fenster“ zu vertreten. send Fenster“, das dort auf Deutsch veröff ent- Zwar erreichte der Schlager über die Ein- licht wurde. MAGAZINDAS DES Der fünfte Sieg für die Niederlande DIE LETZTE SEITE | ections Refl AUSGABE 2019/2020 2 Refl ections 4 Refl ections 99 Refl ections 6 Refl ections IMPRESSUM MARKUS TRITREMMEL MICHAEL STANGL Clubleitung, Generalversammlung, Organisation Clubtreff en, Newsletter, Vorstandssitzung, Newsletter, Tickets Eurovision Song Contest Inlandskorrespondenz, Audioarchiv [email protected] Fichtestraße 77/18 | 8020 Graz MARTIN HUBER [email protected] -

Wreaths to Remember Page 8

=VS5V Thursday, December 21, 2017 WHNL 1HZV)HDWXUHVSDJH >YLH[OZ[VYLTLTILY &UHZFKLHIVNHHS¶HPÁ\LQJ 1HZV)HDWXUHVSDJH 5DUHWDQNHU·VQHZKRPH :HHNLQSKRWRVSDJH ,PDJHVIURPWKHZHHN 1HZV)HDWXUHVSDJH 2SHUDWLRQ&KULVWPDV'URS 7OV[VI`(PYTHUZ[*SHZZ(ZOSL`7LYK\L <: (PY -VYJL :LUPVY (PYTHU 9HJOLS *HJOV HU HPYJYHM[ LSLJ[YPJHS HUK LU]PYVUTLU[HS Z`Z[LTZ HWWYLU[PJL ^P[O [OL [O (PYJYHM[4HPU[LUHUJL:X\HKYVUWSHJLZH^YLH[OVUHNYH]LZP[LK\YPUN[OL>YLH[OZ(JYVZZ(TLYPJH>YLH[O3H`PUNHUK &RPPXQLW\SDJH 9LTLTIYHUJL*LYLTVU`H[[OL-SVYPKH5H[PVUHS*LTL[LY`PU)\ZOULSS-SH+LJ>YLH[OZ(JYVZZ(TLYPJHPZHUVU (YHQWV&KDSHOPRUH WYVMP[VYNHUPaH[PVUKLKPJH[LK[VOVUVYPUNHUK[OHURPUN]L[LYHUZMVY[OLPYZLY]PJLHUKZHJYPMPJL>OH[Z[HY[LKV\[PU(YSPUN[VU 5H[PVUHS*LTL[LY`>HZOPUN[VU+*[OLJLYLTVU`UV^[HRLZWSHJLPUV]LYSVJH[PVUZHJYVZZ[OL^VYSK COMMENTARY (4*JVTTHUKJOPLMYLMSLJ[ZVU`LHYJHYLLY I`*OPLM4HZ[LY:N[:OLSPUH-YL` "JS.PCJMJUZ$PNNBOEDPNNBOEDIJFG SCOTT AIR FORCE BASE, Ill. — Happy holidays! It is a great honor to serve as your command chief. At the end of each year, I take time to re- flect on all Air Mobility Command accomplishments over the year – and this command never ceases to amaze me! This year is no different. AMC enjoyed an extremely successful year be- cause of our Mobility Airmen. With that, I offer you and your families my sincerest thanks. Because of your unwavering commitment to the mission and the support and sacrifices your families make, we are able to generate Rapid Global Mobility for America. As this year comes to a close, I’m especially reflective because this may be my last holiday season on active duty. -

Home • About • Archives • Sitemap • Full Width • Gallery • Contact Us • • • Torpedopop Breaking News I've Been

Brian Wilson: Songwriter, 1962 – 1969 | TorpedoPop | Page 1 of 11 • Home • About • Archives • Sitemap • Full Width • Gallery • Contact us • RSS FEED • MAIL SUBSCRIPTION TorpedoPop Breaking News • I've been listening to the remastered "The Queen Is Dead" this weekend. Sounds great. Nice done and Happy Birthday Johnny Marr! 14 days ago • New review up. The Wrong Words – The Wrong Words http://t.co/p0p8m8n via @ AddToAny 133 days ago • Training 591 days ago http://wenker.se/archives/1507 11/14/2011 Brian Wilson: Songwriter, 1962 – 1969 | TorpedoPop | Page 2 of 11 • News » • Articles » • Reviews » • Torpedo » • Look! Listen! » • Discography • Filmography » Brian Wilson: Songwriter, 1962 – 1969 By Gary Pig Gold On 11/01/2011 At 7:15 Category : Articles , English Tags : beach boys , brian wilson Responses : No Comments 0 Like 16 Share 0 Related Posts • The Beach Boys – The Smile Sessions Box Set 08/27/2011 • “The Greatest Rock Movie You’ve Never Seen,” according to Steven Van Zandt 05/07/2010 http://wenker.se/archives/1507 11/14/2011 Brian Wilson: Songwriter, 1962 – 1969 | TorpedoPop | Page 3 of 11 As we all eagerly await our grand new SMiLE boxes, Gary Pig Gold reminds us of….. TEN REASONS WHY “BRIAN WILSON: SONGWRITER, 1962 – 1969 ” SHOULD BE THE LAST BEACH BOYS DOCUMENTARY YOU NEED EVER WATCH 1. Veteran SoCal socio-musical historian Domenic Priore, sitting alongside a tiki totem beneath a strategically placed orange branch, more than ably launches our story over a wealth of Eastmancolor’d freeway and beach footage, drawing, as only he can, that all-important connection from Gidget to Dick Dale all the way to teenage Brian’s Hawthorne, California music room. -

An Introductory Survey on the Development of Australian Art Song with a Catalog and Bibliography of Selected Works from the 19Th Through 21St Centuries

AN INTRODUCTORY SURVEY ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF AUSTRALIAN ART SONG WITH A CATALOG AND BIBLIOGRAPHY OF SELECTED WORKS FROM THE 19TH THROUGH 21ST CENTURIES BY JOHN C. HOWELL Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University May, 2014 Accepted by the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music. __________________________________________ Mary Ann Hart, Research Director and Chairperson ________________________________________ Gary Arvin ________________________________________ Costanza Cuccaro ________________________________________ Brent Gault ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am indebted to so many wonderful individuals for their encouragement and direction throughout the course of this project. The support and generosity I have received along the way is truly overwhelming. It is with my sincerest gratitude that I extend my thanks to my friends and colleagues in Australia and America. The Australian-American Fulbright Commission in Canberra, ACT, Australia, gave me the means for which I could undertake research, and my appreciation goes to the staff, specifically Lyndell Wilson, Program Manager 2005-2013, and Mark Darby, Executive Director 2000-2009. The staff at the Sydney Conservatorium, University of Sydney, welcomed me enthusiastically, and I am extremely grateful to Neil McEwan, Director of Choral Ensembles, and David Miller, Senior Lecturer and Chair of Piano Accompaniment Unit, for your selfless time, valuable insight, and encouragement. It was a privilege to make music together, and you showed me how to be a true Aussie. The staff at the Australian Music Centre, specifically Judith Foster and John Davis, graciously let me set up camp in their library, and I am extremely thankful for their kindness and assistance throughout the years. -

Lincolnshire Posy Abbig

A Historical and Analytical Research on the Development of Percy Grainger’s Wind Ensemble Masterpiece: Lincolnshire Posy Abbigail Ramsey Stephen F. Austin State University, Department of Music Graduate Research Conference 2021 Dr. David Campo, Advisor April 13, 2021 Ramsey 1 Introduction Percy Grainger’s Lincolnshire Posy has become a staple of wind ensemble repertoire and is a work most professional wind ensembles have performed. Lincolnshire Posy was composed in 1937, during a time when the wind band repertoire was not as developed as other performance media. During his travels to Lincolnshire, England during the early 20th century, Grainger became intrigued by the musical culture and was inspired to musically portray the unique qualities of the locals that shared their narrative ballads through song. While Grainger’s collection efforts occurred in the early 1900s, Lincolnshire Posy did not come to fruition until it was commissioned by the American Bandmasters Association for their 1937 convention. Grainger’s later relationship with Frederick Fennell and Fennell’s subsequent creation of the Eastman Wind Ensemble in 1952 led to the increased popularity of Lincolnshire Posy. The unique instrumentation and unprecedented performance ability of the group allowed a larger audience access to this masterwork. Fennell and his ensemble’s new approach to wind band performance allowed complex literature like Lincolnshire Posy to be properly performed and contributed to establishing wind band as a respected performance medium within the greater musical community. Percy Grainger: Biography Percy Aldridge Grainger was an Australian-born composer, pianist, ethnomusicologist, and concert band saxophone virtuoso born on July 8, 1882 in Brighton, Victoria, Australia and died February 20, 1961 in White Plains, New York.1 Grainger was the only child of John Harry Grainger, a successful traveling architect, and Rose Annie Grainger, a self-taught pianist.