Sarah Kane's Theatrical Legacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996 Stage by Stage The Development of the National Theatre from 1848 Designed by Michael Mayhew Compiled by Lyn Haill & Stephen Wood With thanks to Richard Mangan and The Mander & Mitchenson Theatre Collection, Monica Sollash and The Theatre Museum The majority of the photographs in the exhibition were commissioned by the National Theatre and are part of its archive The exhibition was funded by The Royal National Theatre Foundation Richard Eyre. Photograph by John Haynes. 1988 To mark the company’s 25th birthday in Peter Hall’s last year as Director of the National October, The Queen approves the title ‘Royal’ Theatre. He stages three late Shakespeare for the National Theatre, and attends an plays (The Tempest, The Winter’s Tale, and anniversary gala in the Olivier. Cymbeline) in the Cottesloe then in the Olivier, and leaves to start his own company in the The funds raised are to set up a National West End. Theatre Endowment Fund. Lord Rayne retires as Chairman of the Board and is succeeded ‘This building in solid concrete will be here by the Lady Soames, daughter of Winston for ever and ever, whatever successive Churchill. governments can do to muck it up. The place exists as a necessary part of the cultural scene Prince Charles, in a TV documentary on of this country.’ Peter Hall architecture, describes the National as ‘a way of building a nuclear power station in the September: Richard Eyre takes over as Director middle of London without anyone objecting’. of the National. 1989 Alan Bennett’s Single Spies, consisting of two A series of co-productions with regional short plays, contains the first representation on companies begins with Tony Harrison’s version the British stage of a living monarch, in a scene of Molière’s The Misanthrope, presented with in which Sir Anthony Blunt has a discussion Bristol Old Vic and directed by its artistic with ‘HMQ’. -

'The Left's Views on Israel: from the Establishment of the Jewish State To

‘The Left’s Views on Israel: From the establishment of the Jewish state to the intifada’ Thesis submitted by June Edmunds for PhD examination at the London School of Economics and Political Science 1 UMI Number: U615796 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615796 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 F 7377 POLITI 58^S8i ABSTRACT The British left has confronted a dilemma in forming its attitude towards Israel in the postwar period. The establishment of the Jewish state seemed to force people on the left to choose between competing nationalisms - Israeli, Arab and later, Palestinian. Over time, a number of key developments sharpened the dilemma. My central focus is the evolution of thinking about Israel and the Middle East in the British Labour Party. I examine four critical periods: the creation of Israel in 1948; the Suez war in 1956; the Arab-Israeli war of 1967 and the 1980s, covering mainly the Israeli invasion of Lebanon but also the intifada. In each case, entrenched attitudes were called into question and longer-term shifts were triggered in the aftermath. -

Chapter Three Howard Barker: the Freedom and Constraint of the Artist’S Imagination

80 Chapter Three Howard Barker: The Freedom and Constraint of the Artist’s Imagination During the 1980s, theatrical culture was liable to a variety of political and economic pressures that “produced an enormous sense of dislocation and dissatisfaction”.1 Besides funding cuts, the aesthetic merits of artistic values did not seem to be understood by the politicians. So, theatre was not only subject to funding cuts, but also to censorship, as we shall see. Government interference in performance and writing led to a sense of insecurity. So, works which were economically unviable were threatened with being banned or cancelled. In doing so, the commissioning of artists began to depend entirely on the criteria of the ruling political party – the Conservatives – who ignored the artists’ true feelings. In other words, the aesthetic value of artworks was ignored in favour of monetarism. Instead, the duty of the artist was to be devoted to espousing political ideals. The dilemma of the artist, therefore, was how did artists enjoy a degree of freedom without being censored? And if the artist failed to match the criteria of the ruling political party, what was the price of free expression? All these questions suggest radical changes in the British theatre system which is very complicated ideologically in respect to democracy, sponsorship and how the artists responded to it. Howard Barker is a writer who began to grapple with these questions when he became suspicious of the effectiveness of politically committed theatre at about the same time that Thatcher was elected as Prime Minister. Although he is marginalized in his country, Barker has remained a challenging writer who dismantled the strictness of Conservative values during Thatcher’s time. -

Ian Wooldridge Director

Ian Wooldridge Director For details of Ian's freelance productions, and his international work in training and education go to www.ianwooldridge.com Agents Nicki Stoddart [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0869 Credits Theatre Production Company Notes ARTISTIC DIRECTOR, ROYAL LYCEUM THEATRE COMPANY, EDINBURGH, 1984-1993 THE TAMING OF THE SHREW Royal Lyceum Theatre Shakespeare Company, Edinburgh MERLIN Royal Lyceum Theatre Tankred Dorst Company Edinburgh ROMEO AND JULIET Royal Lyceum Theatre Shakespeare Company Edinburgh THE CRUCIBLE Royal Lyceum Theatre Arthur Miller Company Edinburgh THE ODD COUPLE Royal Lyceum Theatre Neil Simon Company Edinburgh JUNO AND THE PAYCOCK Royal Lyceum Theatre Sean O'Casey Company Edinburgh OTHELLO Royal Lyceum Theatre Shakespeare Company Edinburgh United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes THE HOUSE OF BERNARDA ALBA Royal Lyceum Theatre Federico Garcia Lorca Company Edinburgh HOBSON'S CHOICE Royal Lyceum Theatre Harold Brighouse Company Edinburgh DEATH OF A SALESMAN Royal Lyceum Theatre Arthur Miller Company Edinburgh THE GLASS MENAGERIE Royal Lyceum Theatre Tennessee Williams Company, Edinburgh ALICE IN WONDERLAND Royal Lyceum Theatre Adapted from the novel by Lewis Company, Edinburgh Carroll A MIDSUMMER NIGHT'S DREAM Royal Lyceum Theatre Shakespeare Company Edinburgh A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE Royal Lyceum Theatre Tennessee Williams Company, Edinburgh THE NUTCRACKER SUITE Royal Lyceum -

Prologue: 'After Auschwitz': Survival of the Aesthetic

Notes Prologue: ‘After Auschwitz’: Survival of the Aesthetic 1. In 1959 the German poet Hans Magnus Enzensberger called Adorno’s state- ment ‘one of the harshest judgments that can be made about our times: after Auschwitz it is impossible to write poetry’, and urges that ‘if we want to con- tinue to live, this sentence must be repudiated’. Hans Magnus Enzensberger, ‘Die Steine der Freiheit’ in Petra Kiedaisch (ed.). Lyrik nach Auschwitz? Adorno und die Dichter (73). 2. Herbert Marcuse, too, criticised the tendency toward uniformity and repres- sion of individuality in modern technological society in his seminal 1964 study One-Dimensional Man: Studies in the Ideology of Advanced industrial Society. 3. For philosophers such as Hannah Arendt the culmination of totalitar- ian power as executed in the camps led not only to the degradation and extermination of people, it also opened profound and important questions about our understanding of humanity and ethics (see: Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism). The question of an ethical response to Auschwitz also preoc- cupies Giorgio Agamben who argues that an ethical attempt to bear witness (testimony) to Auschwitz must inevitably confront the impossibility of speak- ing without, however, condemning Auschwitz to the ‘forever incomprehensi- ble’ (Remnants of Auschwitz 11). 4. See Alan Milchman and Alan Rosenberg’s Postmodernism and the Holocaust. However, Adorno’s response to the Holocaust is not discussed in this volume. His most notable reflections on Auschwitz can be found in Negative Dialectics (‘Meditations on Metaphysics’), Metaphysics: Concepts and Problems (1965), and in the collection Can one Live after Auschwitz? 5. -

Sarah Kane's Post-Christian Spirituality in Cleansed

Central Washington University ScholarWorks@CWU All Master's Theses Master's Theses Winter 2020 Sarah Kane's Post-Christian Spirituality in Cleansed Elba Sanchez Central Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd Part of the Performance Studies Commons, Playwriting Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation Sanchez, Elba, "Sarah Kane's Post-Christian Spirituality in Cleansed" (2020). All Master's Theses. 1347. https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd/1347 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses at ScholarWorks@CWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@CWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SARAH KANE’S POST-CHRISTIAN SPIRITUALITY IN CLEANSED __________________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty Central Washington University __________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Theatre Studies __________________________________________ by Elba Marie Sanchez Baez March 2020 CENTRAL WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY Graduate Studies We hereby approve the thesis of Elba Marie Sanchez Baez Candidate for the degree of Master of Arts APPROVED FOR THE GRADUATE FACULTY _____________ __________________________________________ Dr. Emily Rollie, Committee Chair _____________ _________________________________________ Christina Barrigan M.F.A _____________ _________________________________________ Dr. Lily Vuong _____________ _________________________________________ Dean of Graduate Studies ii ABSTRACT SARAH KANE’S POST-CHRISTIAN SPIRITUALITY IN CLEANSED by Elba Marie Sanchez Baez March 2020 The existing scholarship on the work of British playwright Sarah Kane mostly focuses on exploring the use of extreme acts of violence in her plays. -

Investigating the Notion of Catharsis and Probing the Concept of Pain In

حوليات آداب عني مشس اجمللد 46 ) عدد إبريل – يونيه 2018( http://www.aafu.journals.ekb.eg جامعة عني مشس )دورية علمية حملمة( كلية اﻵداب Investigating the Notion of : Beyond the Zone of Comfort Catharsis and Probing the Concept of Pain in Howard Barker's 'Blok/Eko'and Sarah Kane's '4.48 Psychosis'. Neval Nabil Mahmoud Abdullah * Lecture College of Language & Communication - Arab Academy for Science, Technology& Maritime Transport. Abstract: The objective of this paper is to take us on a journey with an odd selection of two enigmatic and controversial British playwrights – Howard Barker and Sarah Kane – whose challenging theatrical works take us well beyond the zone of comfort we might be used to. Through a close textual analysis and a substantial critical evaluation of two crucial productions from the domain of their 'alien to our conception' of dramatic art, the present paper aims at going beyond just surveying their common shock tactics, showing parallels, or pointing out elements of recurrence in their texts. The aim is to get to the bottom of their experiential theatres by considering their transcendental tragic visions for a better exploration of reality and for a possible rebirth of the individual experience. Having explored the dark rooms of Barker's and Kane's self-styled theatres, particularly in their two significant dramatic works – 'Blok/Eko' and '4.48 Psychosis' respectively, the present study discerns that there is a noticeable intent and craft behind both playwrights' crafty 'violations' of the audience's personal space and comfort zones. Barker's and Kane's extremism is part of their attempt to question and criticize the audience's passive participation, foreground an awakening to extreme realities, propose a shift from or challenge to Aristotle's traditional concept of catharsis, and call into question our accepted interpretation of pain. -

Mwm Cv Robinkingsland 2

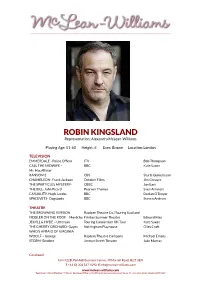

ROBIN KINGSLAND Representation: Alexandra McLean-Williams Playing Age: 51-60 Height: 6’ Eyes: Brown Location: London TELEVISION EMMERDALE - Police Officer ITV Bob Thompson CALL THE MIDWIFE – BBC Kate Saxon Mr. MacAllister RANSOM 3 CBS Sturla Gunnarsson CHAMELEON- Frank Jackson October Films Jim Greayer THE SPARTICLES MYSTERY- CBBC Jon East THE BILL- John Picard Pearson Thames Sven Arnstein CASUALITY-Hugh Jacobs BBC Declan O’Dwyer SPACEVETS- Dogsbody BBC Steven Andrew THEATRE THE BROWNING VERSION Rapture Theatre Co,/Touring Scotland FIDDLER ON THE ROOF – Mordcha Frinton Summer Theatre Edward Max JEKYLL & HYDE – Utterson Touring Consortium UK Tour Kate Saxon THE CHERRY ORCHARD- Gayev Nottingham Playhouse Giles Croft WHO’S AFRAID OF VIRGINIA WOOLF – George Rapture Theatre Company Michael Emans STORM- Brother Jermyn Street Theatre Jake Murray Continued Unit F22B, Parkhall Business Centre, 40 Martell Road, SE21 8EN T +44 (0) 203 567 1090 E [email protected] www.mclean-williams.com Registered in England Number: 7432186 Registered Office: C/O William Sturgess & Co, Burwood House, 14 - 16 Caxton Street, London SW1H 0QY ROBIN KINGSLAND continued PRIVATE LIVES – Victor Mercury Theatre Colchester Esther Richardson ROMEO & JULIET – Montague Crucible Theatre Sheffield Jonathan Humphreys ARCADIA – Captain Bruce Nottingham Playhouse Giles Croft HAMLET- Claudius Secret Theatre, Edinburgh Fringe Richard Crawford Festival THE OTHER PLACE – Ian Smithson RADA Geoffrey Williams WITNESS FOR THE PROSECUTION Vienna English Theatre, Philip Dart Sir Wilfrid -

In Whose Face?! (Angry Young) Theatre Makers and the Targets of Their Provocation

In whose face?! (Angry young) theatre makers and the targets of their provocation Spencer Hazel Hazel, Spencer (2015) In whose face?! (Angry young) theatre makers and the targets of their provocation. In Susan Blattes and Samuel Cuisinier-Delorme (Eds.) Special Issue «Le théâtre In-Yer-Face aujourd’hui: bilans et perspectives», Coup de Theatre, 29, 45-68 1. Introduction The current article offers a response to Aleks Sierz’ (Sierz, 2007) account of how he produced a particular narrative that revolved around a bounded network of theatre practitioners operating in Britain in the latter half of the 1990s, whose work he subsequently labeled as constituting “In-Yer-Face-Theatre” (Sierz 2001). I will be arguing that in order to evaluate any lasting impact that the particular selection of theatre artists have had on current theatre, a modified narrative may serve as a more relevant map through which to chart the developments in UK theatre during what have been termed the “nasty nineties”, and beyond. The alternative narrative that I am proposing may initially seem to offer these players lesser roles in what makes up the grand design of the end-of-the-century British cultural scene, diminishing them from the prime billing that they have enjoyed to date in the work of Sierz and others who have adopted the framework. That is not, however, what I set out to do here. Rather, this new narrative re-incorporates these playwrights into a larger interdisciplinary endeavour that characterized the times in which they happened to be working, an In-Yer-Face decade which was witness to a broader reconceptualization of the possibilities of cultural engagement across a range of forms of expression, both in the performing arts such as theatre, and in other artistic strands like visual art, television and music. -

A Character Type in the Plays of Edward Bond

A Character Type in the Plays of Edward Bond Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Frank A. Torma, M. A. Graduate Program in English The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Jon Erickson, Advisor Richard Green Joy Reilly Copyright by Frank Anthony Torma 2010 Abstract To evaluate a young firebrand later in his career, as this dissertation attempts in regard to British playwright Edward Bond, is to see not the end of fireworks, but the fireworks no longer creating the same provocative results. Pursuing a career as a playwright and theorist in the theatre since the early 1960s, Bond has been the exciting new star of the Royal Court Theatre and, more recently, the predictable producer of plays displaying the same themes and strategies that once brought unsettling theatre to the audience in the decades past. The dissertation is an attempt to evaluate Bond, noting his influences, such as Beckett, Brecht, Shakespeare, and the postmodern, and charting the course of his career alongside other dramatists when it seems appropriate. Edward Bond‟s characters of Len in Saved, the Gravedigger‟s Boy in Lear, Leonard in In the Company of Men, and the character in a number of other Bond plays provide a means to understand Bond‟s aesthetic and political purposes. Len is a jumpy young man incapable of bravery; the Gravedigger‟s Boy is the earnest young man destroyed too early by total war; Leonard is a needy, spoiled youth destroyed by big business. -

Writing Figures of Political Resistance for the British Stage Vol1.Pdf

Writing Figures of Political Resistance for the British Stage Volume One (of Two) Matthew John Midgley PhD University of York Theatre, Film and Television September 2015 Writing Figures of Resistance for the British Stage Abstract This thesis explores the process of writing figures of political resistance for the British stage prior to and during the neoliberal era (1980 to the present). The work of established political playwrights is examined in relation to the socio-political context in which it was produced, providing insights into the challenges playwrights have faced in creating characters who effectively resist the status quo. These challenges are contextualised by Britain’s imperial history and the UK’s ongoing participation in newer forms of imperialism, the pressures of neoliberalism on the arts, and widespread political disengagement. These insights inform reflexive analysis of my own playwriting. Chapter One provides an account of the changing strategies and dramaturgy of oppositional playwriting from 1956 to the present, considering the strengths of different approaches to creating figures of political resistance and my response to them. Three models of resistance are considered in Chapter Two: that of the individual, the collective, and documentary resistance. Each model provides a framework through which to analyse figures of resistance in plays and evaluate the strategies of established playwrights in negotiating creative challenges. These models are developed through subsequent chapters focussed upon the subjects tackled in my plays. Chapter Three looks at climate change and plays responding to it in reflecting upon my creative process in The Ends. Chapter Four explores resistance to the Iraq War, my own military experience and the challenge of writing autobiographically. -

Download Download

S K E N È Journal of Theatre and Drama Studies 5:2 2019 SKENÈ Journal of Theatre and Drama Studies Founded by Guido Avezzù, Silvia Bigliazzi, and Alessandro Serpieri Executive Editor Guido Avezzù. General Editors Guido Avezzù, Silvia Bigliazzi. Editorial Board Simona Brunetti, Francesco Lupi, Nicola Pasqualicchio, Susan Payne, Gherardo Ugolini. Managing Editor Francesco Lupi. Assistant Managing Editors Valentina Adami, Emanuel Stelzer, Roberta Zanoni. Books Reviews Editors Chiara Battisti, Sidia Fiorato Staff Francesco Dall’Olio, Bianca Del Villano, Marco Duranti, Carina Louise Fernandes, Maria Serena Marchesi, Antonietta Provenza, Savina Stevanato. Advisory Board Anna Maria Belardinelli, Anton Bierl, Enoch Brater, Jean-Christophe Cavallin, Richard Allen Cave, Rosy Colombo, Claudia Corti, Marco De Marinis, Tobias Döring, Pavel Drábek, Paul Edmondson, Keir Douglas Elam, Ewan Fernie, Patrick Finglass, Enrico Giaccherini, Mark Griffith, Daniela Guardamagna, Stephen Halliwell, Robert Henke, Pierre Judet de la Combe, Eric Nicholson, Guido Paduano, Franco Perrelli, Didier Plassard, Donna Shalev, Susanne Wofford. Copyright © 2019 SKENÈ Published in December 2019 All rights reserved. ISSN 2421-4353 No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission from the publisher. SKENÈ Theatre and Drama Studies http://skenejournal.skeneproject.it [email protected] Dir. Resp. (aut. Trib. di Verona): Guido Avezzù P.O. Box 149 c/o Mail Boxes Etc. (MBE150) – Viale Col. Galliano, 51, 37138, Verona (I) Contents Manuela Giordano