Charles II: a Man Caught Between Tradition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Court Theatres of the Farnese from 1618 to 1690

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 68—2969 COBES, John Paul, 1932- THE COURT THEATRES OF THE FARNESE FROM 1618 TO 1690. [Figures I-V also IX and X not microfilmed at request of author. Available for consultation at The Ohio State University Library], The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1967 Speech-Theater University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan (S) Copyright by- John Paul Cobes 1968 THE COURT THEATRES OF THE FARNESE FROM 1618 TO 1690 DISSERTATION Presented In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio S tate U niversity By John Paul Cobes, B.S., M.A. ******** The Ohio State University 1967 Approved by Z. Adviser Department of Speech PLEASE NOTE: Figures I-V also IX and X not microfilmed at request of auth or. Available for consultation at The Ohio State University Library. UNIVERSITY MICROFILMS. The author wishes to acknowledge, with dee nest gratitude, the assistance, suggestions, and guidance of the following persons, all of whom were instrumental in the camnletion of this study; Dr. Row H. Bowen, adviser to this study, and all the nersonnel of the Theatre Division of the Deonrtment of Speech at the Ohio State University. Dr. John ft. McDowell and Dr. John q . Morrow, advisers to this study, a".d nil +V> -•ersonnel of the Theatre Collection of the Ohio State Universit.w, D r. A l^ent M ancini of th e I t a l i a n D iv isio n o f th e Romance La.-wn.aTes Department of the Ohio State University’. -

NL-Spring-2020-For-Web.Pdf

RANCHO SAN ANTONIO Boys Home, Inc. 21000 Plummer Street, Chatsworth, CA 91311 (818) 882-6400 Volume 38 No. 1 www.ranchosanantonio.org Spring 2020 God puts rainbows in the clouds so that each of us - in the dreariest and most dreaded moments - can see a possibility of hope. -Maya Angelou A REFLECTION FROM BROTHER JOHN CONNECTING WITH OUR COMMUNITY I would like to share with you a letter from a parent: outh develop a sense of identity and value “Dear All of You at Rancho, Ythrough culture and connections. To increase cultural awareness and With the simplicity of a child, and heart full of sensitivity within our gratitude and appreciation of a parent…I thank Rancho community, each one of you, for your concern and giving of Black History Month yourselves in trying to make one more life a little was celebrated in Febru- happier… ary with a fun and edu- I know they weren’t all happy days nor easy days… cational scavenger hunt some were heartbreaking days… “give up” days… that incorporated impor- so to each of you, thank you. For you to know even tant historical facts. For entertainment, one of our one life has breathed easier because you lived, this very talented staff, a professional saxophone player, is to have succeeded. and his bandmates played Jazz music for our youth Your lives may never touch my son’s again, but I during our celebratory dinner. have faith your labor has not been in vain. And to each one of you young men, I shall pray, with ACTIVITIES DEPARTMENT UPDATE each new life that comes your way… may wisdom guide your tongue as you soothe the hearts of to- ancho’s Activities Department developed a morrow’s men. -

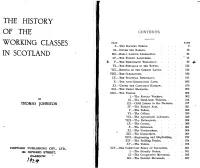

The History of the Working Classes in Scotland

THE HISTORY OF THE CONTENTS. CHAP. WORKING CLASSES I.—THE SLAVERY PERIOD, II.—UNDER THE BARONS, IN SCOTLAND III.—EARLY LABOUR LEGISLATION, IV.—THE FORCED LABOURERS, . $£■ V.—THE DEMOCRATIC THEOCRACY, VI.—THE STRUGGLE IN THE TOWNS, VII.—EEIVING oi" THE COMMON LANDS, VIII.—THE CLEARANCES, IX.—THE POLITICAL DEMOCRACY, X.—THE ANTI-COMBINATION LAWS, XI.—UNDER THE CAPITALIST HARROW, XII.—THE GREAT MASSACRE, XIII.—THE UNIONS, I.—The Factory Workers, BY II.—The Hand-loom Weavers, . THOMAS JOHNSTON III.—Child Labour in the Factories, IV.—The Factory Acts, . V.—The Bakers, VI.-—The Colliers, . VII.—The Agricultural Labourers, VIII.—The Railwaymen, IX.—The Carters, . X.—The Sailormen, XI.—The Woodworkers, XII.—The Ironworkers, XIII.—Engineering and Shipbuilding, XIV.—The Building Trades, XV.—The Tailors, . PORWARD PUBLISHING COY., LTD., XIV.—THE COMMUNIST SEEDS OF SALVATION, I.—The Friendly Orders, 164 HOWARD STREET, II.—The Co-operative Movement, GLASGOW. III.—The Socialist Movement, . tfLf 84 THE HISTORY OF THE WORKING GLASSES. their freedom in the courts, it followed, as a general rule, that the slave was only liberated by death. The result of all these restric CHAPTER V, tions was that coal-mining remained unpopular and the mine-owners in Scotland were still forced to pay higher wages for labour than were THE DEMOCRATIC THEOCRACY. their English confreres. And so the liberating Act of 1799, which " The Solemn League and Covenant finally abolished slavery in the coal mines and saltpans of Scotland, Whiles brings a sigh and whiles a tear; was urged upon Parliament by the more far-seeing coalowners them But Sacred Freedom, too, was there, selves. -

White Priory Murders

THE WHITE PRIORY MURDERS John Dickson Carr Writing as Carter Dickson CHAPTER ONE Certain Reflections in the Mirror "HUMPH," SAID H. M., "SO YOU'RE MY NEPHEW, HEY?" HE continued to peer morosely over the tops of his glasses, his mouth turned down sourly and his big hands folded over his big stomach. His swivel chair squeaked behind the desk. He sniffed. 'Well, have a cigar, then. And some whisky. - What's so blasted funny, hey? You got a cheek, you have. What're you grinnin' at, curse you?" The nephew of Sir Henry Merrivale had come very close to laughing in Sir Henry Merrivale's face. It was, unfortu- nately, the way nearly everybody treated the great H. M., including all his subordinates at the War Office, and this was a very sore point with him. Mr. James Boynton Bennett could not help knowing it. When you are a young man just arrived from over the water, and you sit for the first time in the office of an eminent uncle who once managed all the sleight-of-hand known as the British Military Intelligence Department, then some little tact is indicated. H. M., although largely ornamental in these slack days, still worked a few wires. There was sport, and often danger, that came out of an unsettled Europe. Bennett's father, who was H. M.'s brother-in-law and enough of a somebody at Washington to know, had given him some extra-family hints before Bennett sailed. "Don't," said the elder Bennett, "don't, under any circumstances, use any ceremony with him. -

News Release

NEWS RELEASE FOURTH STREET AT CONSTITUTION AVENUE NW WASHINGTON DC 20565 . 737-4215/842-6353 EXHBITION FACT SHEET Title; THE TREASURE HOUSES OF BRITAIN: FIVE HUNDRED YEARS OF PRIVATE PATRONAGE AND ART COLLECTING Patrons: Their Royal Highnesses The Prince and Princess of Wales Dates; November 3, 1985 through March 16, 1986, exactly one week later than previously announced. (This exhibition will not travel. Loans from houses open to view are expected to remain in place until the late summer of 1985 and to be returned before many of the houses open for their visitors in the spring of 1986.) Credits; This exhibition is made possible by a generous grant from the Ford Motor Company. The exhibition was organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, in collaboration v\n.th the British Council and is supported by indemnities from Her Majesty's Treasury and the U.S. Federal Council on the Arts and Humanities. Further British assistance was supplied by the National Trust and the Historic Houses Association. History of the exhibition; The suggestion that the National Gallery of Art consider holding a major exhibition devoted to British art was made by the British Council in 1979. J. Carter Brown, Director of the National Gallery, responded with the idea of an exhibition on the British Country House as a "vessel of civilization," bringing together works of art illustrating the extraordinary achievement of collecting and patronage throughout Britain over the past five hundred years. As this concept carried with it the additional, contemporary advantage of stimulating greater interest in and support of those houses open to public viewing, it was enthusiastically endorsed by the late Lord Howard of Henderskelfe, then-Chairman of the Historic Houses Association, Julian Andrews, Director of the Fine Arts Department of the British Council, and Lord Gibson, Chairman of the National Trust. -

Historical Influence of the Rosicrucian Fraternity on Freemasonry

Historical Influence of the Rosicrucian Fraternity on Freemasonry Introduction Freemasonry has a public image that sometimes includes notions that we practice some sort of occultism, alchemy, magic rituals, that sort of thing. As Masons we know that we do no such thing. Since 1717 we have been a modern, rational, scientifically minded craft, practicing moral and theological virtues. But there is a background of occult science in Freemasonry, and it is related to the secret fraternity of the Rosicrucians. The Renaissance Heritage1 During the Italian renaissance of the 15th century, scholars rediscovered and translated classical texts of Plato, Pythagoras, and the Hermetic writings attributed to Hermes Trismegistus, thought to be from ancient Egypt. Over the next two centuries there was a widespread growth in Europe of various magical and spiritual practices – magic, alchemy, astrology -- based on those texts. The mysticism and magic of Jewish Cabbala was also studied from texts brought from Spain and the Muslim world. All of these magical practices had a religious aspect, in the quest for knowledge of the divine order of the universe, and Man’s place in it. The Hermetic vision of Man was of a divine soul, akin to the angels, within a material, animal body. By the 16th century every royal court in Europe had its own astrologer and some patronized alchemical studies. In England, Queen Elizabeth had Dr. John Dee (1527- 1608) as one of her advisors and her court astrologer. Dee was also an alchemist, a student of the Hermetic writings, and a skilled mathematician. He was the most prominent practitioner of Cabbala and alchemy in 16th century England. -

Commissaires-Priseurs BEAUSSANT LEFÈVRE 4 JUIN 2008

BEAUSSANT_COUV 7/05/08 8:08 Page 1 Commissaires-Priseurs BEAUSSANT LEFÈVRE 4 JUIN 2008 32, rue Drouot, 75009 PARIS Tél. : 00 33 (0)1 47 70 40 00 - Fax : 00 33 (0)1 47 70 62 40 www.beaussant-lefevre.com E-mail : [email protected] Société de Ventes Volontaires - Sarl au capital de 7 600 € - Siren n° 443 080 338 - Agrément n° 2002 - 108 Eric BEAUSSANT et Pierre-Yves LEFÈVRE, Commissaires-Priseurs PARIS - DROUOT-RICHELIEU PARIS PARIS - DROUOT - MERCREDI 4 JUIN 2008 BEAUSSANT_COUV 7/05/08 8:08 Page 2 Inscrivez-vous à la newsletter de l’étude par mail sur notre site www.beaussant-lefevre.com BEAUSSANT_1_20 6/05/08 15:40 Page 1 LES COURSES et LA CHASSE DOCUMENTATION - GRAVURES - TABLEAUX - SCULPTURES DÉCORATIONS - ARMES - MILITARIA COLLECTION de STATUETTES en bronze de Vienne COLLECTION d’OBJETS à décor tartan VENTE AUX ENCHÈRES PUBLIQUES Le MERCREDI 4 JUIN 2008 à 14 heures Par le Ministère de : Mes Eric BEAUSSANT et Pierre-Yves LEFÈVRE Commissaires-Priseurs BEAUSSANT LEFÈVRE Société de ventes volontaires Siren n° 443 080 338 - Agrément n° 2002-108 32, rue Drouot - 75009 PARIS Tél. : 01 47 70 40 00 - Télécopie : 01 47 70 62 40 www.beaussant-lefevre.com E-mail : [email protected] PARIS - DROUOT RICHELIEU - Salle no 4 9, rue Drouot, 75009 Paris, Tél. : 01 48 00 20 20 - Fax : 01 48 00 20 33 EXPOSITIONS PUBLIQUES : Mardi 3 Juin 2008 de 11 h à 18 h Mercredi 4 Juin 2008 de 11 h à 12 h Téléphone pendant les expositions et la vente : 01 48 00 20 04 En couverture : détail du n° 132 BEAUSSANT_1_20 6/05/08 15:40 Page 2 EXPERTS : Estampes : M. -

Animal Painters of England from the Year 1650

JOHN A. SEAVERNS TUFTS UNIVERSITY l-IBRAHIES_^ 3 9090 6'l4 534 073 n i«4 Webster Family Librany of Veterinary/ Medicine Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tuits University 200 Westboro Road ^^ Nortli Grafton, MA 01536 [ t ANIMAL PAINTERS C. Hancock. Piu.xt. r.n^raied on Wood by F. Bablm^e. DEER-STALKING ; ANIMAL PAINTERS OF ENGLAND From the Year 1650. A brief history of their lives and works Illustratid with thirty -one specimens of their paintings^ and portraits chiefly from wood engravings by F. Babbage COMPILED BV SIR WALTER GILBEY, BART. Vol. II. 10116011 VINTOX & CO. 9, NEW BRIDGE STREET, LUDGATE CIRCUS, E.C. I goo Limiiei' CONTENTS. ILLUSTRATIONS. HANCOCK, CHARLES. Deer-Stalking ... ... ... ... ... lo HENDERSON, CHARLES COOPER. Portrait of the Artist ... ... ... i8 HERRING, J. F. Elis ... 26 Portrait of the Artist ... ... ... 32 HOWITT, SAMUEL. The Chase ... ... ... ... ... 38 Taking Wild Horses on the Plains of Moldavia ... ... ... ... ... 42 LANDSEER, SIR EDWIN, R.A. "Toho! " 54 Brutus 70 MARSHALL, BENJAMIN. Portrait of the Artist 94 POLLARD, JAMES. Fly Fishing REINAGLE, PHILIP, R.A. Portrait of Colonel Thornton ... ... ii6 Breaking Cover 120 SARTORIUS, JOHN. Looby at full Stretch 124 SARTORIUS, FRANCIS. Mr. Bishop's Celebrated Trotting Mare ... 128 V i i i. Illustrations PACE SARTORIUS, JOHN F. Coursing at Hatfield Park ... 144 SCOTT, JOHN. Portrait of the Artist ... ... ... 152 Death of the Dove ... ... ... ... 160 SEYMOUR, JAMES. Brushing into Cover ... 168 Sketch for Hunting Picture ... ... 176 STOTHARD, THOMAS, R.A. Portrait of the Artist 190 STUBBS, GEORGE, R.A. Portrait of the Duke of Portland, Welbeck Abbey 200 TILLEMAN, PETER. View of a Horse Match over the Long Course, Newmarket .. -

Puritans and the Royal Society

Faith and Thought A Journal devoted to the study of the inter-relation of the Christian revelation and modern research Vol. 92 Number 2 Winter 1961 C. E. A. TURNER, M.Sc., PH.D. Puritans and the Royal Society THE official programme of the recent tercentenary celebrations of the founding of the Royal Society included a single religious service. This was held at 10.30 a.m. at St Paul's Cathedral when the Dean, the Very Rev. W. R. Matthews, D.D., D.LITT., preached a sermon related to the building's architect, Sir Christopher Wren. Otherwise there seems to be little reference to the religious background of the Society's pioneers and a noticeable omission of appreciation of the considerable Puritan participation in its institution. The events connected with the Royal Society's foundation range over the period 1645 to 1663, but there were also earlier influences. One of these was Sir Francis Bacon, Lord Verulam, 1561-1626. Douglas McKie, Professor of the History and Philosophy of Science, University College, London, in The Times Special Number, 19 July 1960, states that Bacon's suggested academy called Solomon's House described in New Atlantis (1627) was too often assumed to be influential in the founding of the Royal Society, much in the same way as Bacon's method of induction, expounded in his Novum Organum of 1620, has been erroneously regarded as a factor in the rise of modern science. But this may be disputed, for Bacon enjoyed considerable prestige as a learned man and his works were widely read. -

The Shiloh Letters of George W. Lennard

“Give Yourself No Trouble About Me”: The Shiloh Letters of George W. Lennard Edited by Paul Hubbard and Christine Lewis” Hoosiers were stout defenders of the Union in the Civil War, and one who came forward willingly to serve and die was George W. Lennard. When the Thirty-sixth Indiana Volunteer Infantry regiment was organized in September, 1861, Lennard joined its ranks as a private soldier but was immediately elected lieutenant and named as adjutant. His duty with the Thirty-sixth was short-lived, however, because within weeks he was made a captain and assigned as aide-de-camp to Brigadier General Thomas J. Wood, who in the Shiloh campaign com- manded the Sixth Division of Major General Don Carlos Buell’s Army of the Ohio. Shortly before the battle of Murfreesboro, or Stone’s River, December 31, 1862-January 2, 1863, Lennard was commissioned lieutenant colonel of the Fifty-seventh Indi- ana Volunteer Infantry, and at that battle he was wounded while fighting with his regiment. After convalescing in the spring of 1863, he rejoined his unit for the campaign against Chattanooga under Major General William S. Rosecrans. When the Federal forces occupied that city in September, 1863, Len- nard was detailed as provost marshal, and he had no part in the Battle of Chickamauga. The Fifty-seventh Indiana, how- ever, did participate in the storming of Missionary Ridge in November, and Lennard escaped unscathed in that dramatic assault. In the spring of 1864 fortune deserted him, and as the Army of the Cumberland marched toward Atlanta, he was wounded at Resaca, Georgia, on the afternoon of May 14 and died that evening.’ * Paul Hubbard is professor of history, Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona. -

The Phantom on Film: Guest Editor’S Introduction

The Phantom on Film: Guest Editor’s Introduction [accepted for publication in The Opera Quarterly, Oxford University Press] © Cormac Newark 2018 What has the Phantom got to do with opera? Music(al) theater sectarians of all denominations might dismiss the very question, but for the opera studies community, at least, it is possible to imagine interesting potential answers. Some are historical, some technical, and some to do with medium and genre. Others are economic, invoking different commercial models and even (in Europe at least) complex arguments surrounding public subsidy. Still others raise, in their turn, further questions about the historical and contemporary identities of theatrical institutions and the productions they mount, even the extent to which particular works and productions may become institutions themselves. All, I suggest, are in one way or another related to opera reception at a particular time in the late nineteenth century: of one work in particular, Gounod’s Faust, but even more to the development of a set of popular ideas about opera and opera-going. Gaston Leroux’s serialized novel Le Fantôme de l’Opéra, set in and around the Palais Garnier, apparently in 1881, certainly explores those ideas in a uniquely productive way.1 As many (but perhaps not all) readers will recall, it tells the story of the debut in a principal role of Christine Daaé, a young Swedish soprano who is promoted when the Spanish prima donna, Carlotta, is indisposed.2 In the course of a gala performance in honor of the outgoing Directors of the Opéra, she is a great success in extracts of works 1 The novel was serialized in Le Gaulois (23 September 1909–8 January 1910) and then published in volume-form: Le Fantôme de l’Opéra (Paris: Lafitte, 1910). -

The Artistic Approach of the Grieve Family to Selected Problems of Nineteenth Century Scene Painting

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 67-6318 HAMBLIN, Junius N., 1930- THE ARTISTIC APPROACH OF THE GRIEVE FAMILY TO SELECTED PROBLEMS OF NINETEENTH CENTURY SCENE PAINTING. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1966 Speech-Theater University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan C Copyright by Junius N. Hamblin 1967 THE ARTISTIC APPROACH OF THE GRIEVE FAMILY TO SELECTED PROBLEMS OF NINETEENTH CENTURY SCENE PAINTING DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Junius N . Hamblin* B .S.* M.S. ****** The Ohio State University 1966 Approved by Department of Speech PLEASE NOTE: Figure pages are not original copy. They tend to "curl". Filmed in the best possible way. UNIVERSITY MICROFILMS PREFACE The conduct of this investigation would not have been possible without the large number of drawings by members of the Grieve family available for analysis through the microfilm holdings of The Ohio State University Theatre Collection. These holdings are from three sources: (l) The British Museum collection of drawings by John Henderson Grieve (OSUTC film No. 1454). (2) The Victoria and Albert Museum holdings of drawings by members of the Grieve family (OSUTC film No. 1721). It is from these two sources that the drawings were selected for analysis and illustration in this study. (3) Drawings by Thomas Grieve in the Charles Kean Collection at the Victoria and Albert Museum (OSUTC film Nos. 893, 894 and 895 )• These drawings are catalogued in Appendix A and were examined but were not used as illustrations for the study because they are from the second half of the century when theatrical conditions had begun to change.