The Artistic Approach of the Grieve Family to Selected Problems of Nineteenth Century Scene Painting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joseph Grimaldi

Joseph Grimaldi The most famous and popular of all the clowns in harlequinade and pantomime was Joseph Grimaldi. Despite his Italian name and family origins, he was born in London in 1779, dying in 1837. His style of clowning had its origins in the Italian commedia dell'arte of the sixteenth century, but in the popular Harlequinades of the early nineteenth century he emerged as the founding father of modern day clowns. To this day he is commemorated annually by clowns in their own church, Holy Trinity in Dalston, East London. Joseph Grimaldi was the original 'Clown Joey', the term 'Joey' being used to describe clowns since his day. Of his own name he punned 'I am grim all day - but I make you laugh at night!' Grimaldi became the most popular clown in pantomime, and was responsible for establishing the clown as the main character in the Harlequinade, in place of Harlequin. His career began at the age of three at the Sadler's Wells Theatre. He was later to become the mainstay of the Drury Lane Theatre before settling in at Covent Garden in 1806. His three year contract paid him one pound a week, rising to two pounds the following year, and finally three pounds a week. His debut at Covent Garden was in 'Harlequin and Mother Goose; or the Golden Egg' in 1806. Grimaldi himself had little faith in the piece, and undoubtedly it was hastily put together on a sparsely decorated stage. However, the production ran for 92 nights, and took over £20,000. The lack of great theatrical scenes allowed Grimaldi to project himself to the fore 'he shone with unimpeded brilliance' once critic wrote. -

M a K in G a N D U N M a K in Gin Early Modern English Drama

Porter MAKING AND Chloe Porter UNMAKING IN EARLY MODERN ENGLISH DRAMA Why are early modern English dramatists preoccupied with unfinished processes of ‘making’ and ‘unmaking’? And what did ‘finished’ or ‘incomplete’ mean for spectators of plays and visual works in this period? Making and unmaking in early IN EARLY MODERN ENGLISH DRAMA IN EARLY UNMAKING AND MAKING modern English drama is about the prevalence and significance of visual things that are ‘under construction’ in early modern plays. Contributing to challenges to the well-worn narrative of ‘iconophobic’ early modern English culture, it explores the drama as a part of a lively post-Reformation visual world. Interrogating the centrality of concepts of ‘fragmentation’ and ‘wholeness’ in critical approaches to this period, it opens up new interpretations of the place of aesthetic form in early modern culture. An interdisciplinary study, this book argues that the idea of ‘finish’ had transgressive associations in the early modern imagination. It centres on the depiction of incomplete visual practices in works by playwrights including Shakespeare, John Lyly, and Robert Greene. The first book of its kind to connect dramatists’ attitudes to the visual with questions of materiality, Making and Unmaking in Early Modern English Drama draws on a rich range of illustrated examples. Plays are discussed alongside contexts and themes, including iconoclasm, painting, sculpture, clothing and jewellery, automata, and invisibility. Asking what it meant for Shakespeare and his contemporaries to ‘begin’ or ‘end’ a literary or visual work, this book is invaluable for scholars and students of early modern English literature, drama, visual culture, material culture, theatre history, history and aesthetics. -

Visions of Vietnam

DATA BOOK STAKES RESULTS European Pattern 2008 : HELLEBORINE (f Observatory) 3 wins at 2, wins in USA, Mariah’s Storm S, 2nd Gardenia H G3 . 277 PARK HILL S G2 Prix d’Aumale G3 , Prix Six Perfections LR . 280 DONCASTER CUP G2 Dam of 2 winners : 2010 : (f Observatory) 2005 : CONCHITA (f Cozzene) Winner at 3 in USA. DONCASTER. Sep 9. 3yo+f&m. 14f 132yds. DONCASTER. September 10. 3yo+. 18f. 2006 : Towanda (f Dynaformer) 1. EASTERN ARIA (UAE) 4 9-4 £56,770 2nd Dam : MUSICANTI by Nijinsky. 1 win in France. 1. SAMUEL (GB) 6 9-1 £56,770 2008 : WHITE MOONSTONE (f Dynaformer) 4 wins b f by Halling - Badraan (Danzig) Dam of DISTANT MUSIC (c Distant View: Dewhurst ch g by Sakhee - Dolores (Danehill) at 2, Meon Valley Stud Fillies’ Mile S G1 , O- Sheikh Hamdan Bin Mohammed Al Maktoum S G1 , 3rd Champion S G1 ), New Orchid (see above) O/B- Normandie Stud Ltd TR- JHM Gosden Keepmoat May Hill S G2 , germantb.com Sweet B- Darley TR- M Johnston 2. Tastahil (IRE) 6 9-1 £21,520 Solera S G3 . 2. Rumoush (USA) 3 8-6 £21,520 Broodmare Sire : QUEST FOR FAME . Sire of the ch g by Singspiel - Luana (Shaadi) 2009 : (f Arch) b f by Rahy - Sarayir (Mr Prospector) dams of 24 Stakes winners. In 2010 - SKILLED O- Hamdan Al Maktoum B- Darley TR- BW Hills 2010 : (f Tiznow) O- Hamdan Al Maktoum B- Shadwell Farm LLC Commands G1, TAVISTOCK Montjeu G1, SILVER 3. Motrice (GB) 3 7-12 £10,770 TR- MP Tregoning POND Act One G2, FAMOUS NAME Dansili G3, gr f by Motivator - Entente Cordiale (Affirmed) 2nd Dam : DESERT STORMETTE by Storm Cat. -

Grosvenor Prints 19 Shelton Street Covent Garden London WC2H 9JN

Grosvenor Prints 19 Shelton Street Covent Garden London WC2H 9JN Tel: 020 7836 1979 Fax: 020 7379 6695 E-mail: [email protected] www.grosvenorprints.com Dealers in Antique Prints & Books Prints from the Collection of the Hon. Christopher Lennox-Boyd Arts 3801 [Little Fatima.] [Painted by Frederick, Lord Leighton.] Gerald 2566 Robinson Crusoe Reading the Bible to Robinson. London Published December 15th 1898 by his Man Friday. "During the long timer Arthur Lucas the Proprietor, 31 New Bond Street, W. Mezzotint, proof signed by the engraver, ltd to 275. that Friday had now been with me, and 310 x 490mm. £420 that he began to speak to me, and 'Little Fatima' has an added interest because of its understand me. I was not wanting to lay a Orientalism. Leighton first showed an Oriental subject, foundation of religious knowledge in his a `Reminiscence of Algiers' at the Society of British mind _ He listened with great attention." Artists in 1858. Ten years later, in 1868, he made a Painted by Alexr. Fraser. Engraved by Charles G. journey to Egypt and in the autumn of 1873 he worked Lewis. London, Published Octr. 15, 1836 by Henry in Damascus where he made many studies and where Graves & Co., Printsellers to the King, 6 Pall Mall. he probably gained the inspiration for the present work. vignette of a shipwreck in margin below image. Gerald Philip Robinson (printmaker; 1858 - Mixed-method, mezzotint with remarques showing the 1942)Mostly declared pirnts PSA. wreck of his ship. 640 x 515mm. Tears in bottom Printsellers:Vol.II: margins affecting the plate mark. -

Haras La Pasion

ÍNDICE GENERAL ÍNDICE GANADORES CLÁSICOS REFERENCIA DE PADRILLOS EASING ALONG VIOLENCE MANIPULATOR LIZARD ISLAND SIXTIES ICON ZENSATIONAL SANTILLANO SABAYON HURRICANE CAT JOHN F KENNEDY GALAN DE CINE POTRILLOS POTRANCAS NOTAS CÓMO LLEGAR ÍNDICE POTRILLOS POTRILLOS 1 ES CALIU Easing Along - Entidad Suprema por Rock Hard Ten 2 EL IMPENETRABLE Violence - La Imparcial por Easing Along 3 VITARO Violence - Vlytava por Southern Halo 4 PADRICIANO Violence - Petrova por Southern Halo 5 BOLLANI Manipulator - Be My Baby por Exchange Rate 6 LEONCINO Manipulator - Latoscana por Sea The Stars 7 ONDEADOR Manipulator - Onda Chic por Easing Along 8 ARDE DENTRO Manipulator - Arde La Ciudad por Stormy Atlantic 9 LINCE IBERICO Manipulator - Linkwoman por Southern Halo 10 FANATICO MISTICO Manipulator - Fancy Kitty por Easing Along 11 MUY SARDINERO Manipulator - Monaguesca por Easing Along 12 DON BERTONI Manipulator - Dayli por Mutakddim 13 ANANA FIZZ Manipulator - Anantara por Exchange Rate 14 MUÑECO VUDU Manipulator - Muñeca Lista por Lizard Island 15 CARROBBIO Lizard Island - Cookie Crisp por Mutakddim 16 SAN DOMENICO Lizard Island - Saratogian por Candy Ride 17 ENTRE VOS Y YO Sixties Icon - Entretiempo por Exchange Rate 18 SAGARDOY Sixties Icon - Sagardoa por Easing Along 19 CILINDRO Sixties Icon - Cilindrada por Touch Gold 20 DON BASSI Sixties Icon - Devotion Unbridled por Unbridled 21 ILUMINISMO Sixties Icon - Ilegalidad por Easing Along 22 BUEN BELGA Zensational - Buenas Costumbres por Honour And Glory 23 LEON AMERICANO Zensational - Leandrinha por Bernstein -

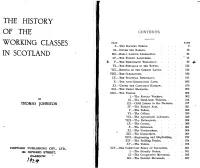

The History of the Working Classes in Scotland

THE HISTORY OF THE CONTENTS. CHAP. WORKING CLASSES I.—THE SLAVERY PERIOD, II.—UNDER THE BARONS, IN SCOTLAND III.—EARLY LABOUR LEGISLATION, IV.—THE FORCED LABOURERS, . $£■ V.—THE DEMOCRATIC THEOCRACY, VI.—THE STRUGGLE IN THE TOWNS, VII.—EEIVING oi" THE COMMON LANDS, VIII.—THE CLEARANCES, IX.—THE POLITICAL DEMOCRACY, X.—THE ANTI-COMBINATION LAWS, XI.—UNDER THE CAPITALIST HARROW, XII.—THE GREAT MASSACRE, XIII.—THE UNIONS, I.—The Factory Workers, BY II.—The Hand-loom Weavers, . THOMAS JOHNSTON III.—Child Labour in the Factories, IV.—The Factory Acts, . V.—The Bakers, VI.-—The Colliers, . VII.—The Agricultural Labourers, VIII.—The Railwaymen, IX.—The Carters, . X.—The Sailormen, XI.—The Woodworkers, XII.—The Ironworkers, XIII.—Engineering and Shipbuilding, XIV.—The Building Trades, XV.—The Tailors, . PORWARD PUBLISHING COY., LTD., XIV.—THE COMMUNIST SEEDS OF SALVATION, I.—The Friendly Orders, 164 HOWARD STREET, II.—The Co-operative Movement, GLASGOW. III.—The Socialist Movement, . tfLf 84 THE HISTORY OF THE WORKING GLASSES. their freedom in the courts, it followed, as a general rule, that the slave was only liberated by death. The result of all these restric CHAPTER V, tions was that coal-mining remained unpopular and the mine-owners in Scotland were still forced to pay higher wages for labour than were THE DEMOCRATIC THEOCRACY. their English confreres. And so the liberating Act of 1799, which " The Solemn League and Covenant finally abolished slavery in the coal mines and saltpans of Scotland, Whiles brings a sigh and whiles a tear; was urged upon Parliament by the more far-seeing coalowners them But Sacred Freedom, too, was there, selves. -

City, University of London Institutional Repository

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pick, J.M. (1980). The interaction of financial practices, critical judgement and professional ethics in London West End theatre management 1843-1899. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/7681/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] THE INTERACTION OF FINANCIAL PRACTICES, CRITICAL JUDGEMENT AND PROFESSIONAL ETHICS IN LONDON WEST END THEATRE MANAGEMENT 1843 - 1899. John Morley Pick, M. A. Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the City University, London. Research undertaken in the Centre for Arts and Related Studies (Arts Administration Studies). October 1980, 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements 4 Abstract 5 One. Introduction: the Nature of Theatre Management 1843-1899 6 1: a The characteristics of managers 9 1: b Professional Ethics 11 1: c Managerial Objectives 15 1: d Sources and methodology 17 Two. -

Italian Theater Prints, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt9b69q7n7 No online items Finding aid for the Italian theater prints, ca. 1550-1983 Finding aid prepared by Rose Lachman and Karen Meyer-Roux. Finding aid for the Italian theater P980004 1 prints, ca. 1550-1983 Descriptive Summary Title: Italian theater prints Date (inclusive): circa 1550-1983 Number: P980004 Physical Description: 21.0 box(es)21 boxes, 40 flat file folders ca. 677 items (623 prints, 13 drawings, 23 broadsides, 16 cutouts, 1 pamphlet, 1 score) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles, California, 90049-1688 (310) 440-7390 Abstract: The Italian theater prints collection documents the development of stage design, or scenography, the architecture of theaters, and the iconography of commedia dell'arte characters and masks. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in Italian Access Open for use by qualified researchers. Publication Rights Contact Library Reproductions and Permissions . Preferred Citation Italian theater prints, ca. 1550-1983, Getty Research Institute, Research Library, Accession no. P980004. http://hdl.handle.net/10020/cifaP980004 Acquisition Information Acquired in 1998. Processing History The Italian theater prints collection was first processed in 1998 by Rose Lachman. Karen Meyer-Roux completed the processing of the collection and wrote the present finding aid in 2004. Separated Materials All of the approximately 4380 secondary sources from the Italian theater collection were separated to the library. In addition, ca. 1500 rare books, some of which are illustrated with prints, have also been separately housed, processed and cataloged. -

American Punk: the Relations Between Punk Rock, Hardcore, and American Culture

American Punk: The Relations between Punk Rock, Hardcore, and American Culture Gerfried Ambrosch ABSTRACT Punk culture has its roots on both sides of the Atlantic. Despite continuous cross-fertiliza- tion, the British and the American punk traditions exhibit distinct features. There are notable aesthetic and lyrical differences, for instance. The causes for these dissimilarities stem from the different cultural, social, and economic preconditions that gave rise to punk in these places in the mid-1970s. In the U. K., punk was mainly a movement of frustrated working-class youths who occupied London’s high-rise blocks and whose families’ livelihoods were threatened by a declin- ing economy and rising unemployment. Conversely, in America, punk emerged as a middle-class phenomenon and a reaction to feelings of social and cultural alienation in the context of suburban life. Even city slickers such as the Ramones, New York’s counterpart to London’s Sex Pistols and the United States’ first ‘official’ well-known punk rock group, made reference to the mythology of suburbia (not just as a place but as a state of mind, and an ideal, as well), advancing a subver- sive critique of American culture as a whole. Engaging critically with mainstream U.S. culture, American punk’s constitutive other, punk developed an alternative sense of Americanness. Since the mid-1970s, punk has produced a plethora of bands and sub-scenes all around the world. This phenomenon began almost simultaneously on both sides of the Atlantic—in London and in New York, to be precise—and has since spread to the most remote corners of the world. -

White Priory Murders

THE WHITE PRIORY MURDERS John Dickson Carr Writing as Carter Dickson CHAPTER ONE Certain Reflections in the Mirror "HUMPH," SAID H. M., "SO YOU'RE MY NEPHEW, HEY?" HE continued to peer morosely over the tops of his glasses, his mouth turned down sourly and his big hands folded over his big stomach. His swivel chair squeaked behind the desk. He sniffed. 'Well, have a cigar, then. And some whisky. - What's so blasted funny, hey? You got a cheek, you have. What're you grinnin' at, curse you?" The nephew of Sir Henry Merrivale had come very close to laughing in Sir Henry Merrivale's face. It was, unfortu- nately, the way nearly everybody treated the great H. M., including all his subordinates at the War Office, and this was a very sore point with him. Mr. James Boynton Bennett could not help knowing it. When you are a young man just arrived from over the water, and you sit for the first time in the office of an eminent uncle who once managed all the sleight-of-hand known as the British Military Intelligence Department, then some little tact is indicated. H. M., although largely ornamental in these slack days, still worked a few wires. There was sport, and often danger, that came out of an unsettled Europe. Bennett's father, who was H. M.'s brother-in-law and enough of a somebody at Washington to know, had given him some extra-family hints before Bennett sailed. "Don't," said the elder Bennett, "don't, under any circumstances, use any ceremony with him. -

THE HONOURABLE HISTORY of FRIAR BACON and FRIAR BUNGAY

ElizabethanDrama.org presents the Annotated Popular Edition of THE HONOURABLE HISTORY of FRIAR BACON and FRIAR BUNGAY By Robert Greene Written c. 1590 Earliest Extant Edition: 1594 Featuring complete and easy-to-read annotations. Annotations and notes © Copyright Peter Lukacs and ElizabethanDrama.org, 2020. This annotated play may be freely copied and distributed. THE HONOURABLE HISTORY of FRIAR BACON and FRIAR BUNGAY by Robert Greene Written c. 1590 Earliest Extant Edition: 1594 DRAMATIS PERSONAE INTRODUCTION to the PLAY King Henry the Third. Robert Greene's Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay may be Edward, Prince of Wales, his Son. thought of as a companion-play to Christopher Marlowe's Raphe Simnell, the King’s Fool. Doctor Faustus: the protagonist in each drama is a sorcerer Lacy, Earl of Lincoln. who conjures devils and impresses audiences with great Warren, Earl of Sussex. feats of magic. Friar Bacon is, however, a superior and Ermsby, a Gentleman. much more interesting play, containing as it does the secondary plot of Prince Edward and his pursuit of the fair Friar Bacon. maiden Margaret. Look out also for the appearance of one Miles, Friar Bacon’s Poor Scholar. of Elizabethan drama's most famous stage props, the giant Friar Bungay. talking brass head. Emperor of Germany. OUR PLAY'S SOURCE King of Castile. Princess Elinor, Daughter to the King of Castile. The text of the play is adapted primarily from the 1876 Jaques Vandermast, A German Magician. edition of Greene's plays edited by Alexander Dyce, but with much original wording and spelling reinstated from the Doctors of Oxford: quarto of 1594. -

Commissaires-Priseurs BEAUSSANT LEFÈVRE 4 JUIN 2008

BEAUSSANT_COUV 7/05/08 8:08 Page 1 Commissaires-Priseurs BEAUSSANT LEFÈVRE 4 JUIN 2008 32, rue Drouot, 75009 PARIS Tél. : 00 33 (0)1 47 70 40 00 - Fax : 00 33 (0)1 47 70 62 40 www.beaussant-lefevre.com E-mail : [email protected] Société de Ventes Volontaires - Sarl au capital de 7 600 € - Siren n° 443 080 338 - Agrément n° 2002 - 108 Eric BEAUSSANT et Pierre-Yves LEFÈVRE, Commissaires-Priseurs PARIS - DROUOT-RICHELIEU PARIS PARIS - DROUOT - MERCREDI 4 JUIN 2008 BEAUSSANT_COUV 7/05/08 8:08 Page 2 Inscrivez-vous à la newsletter de l’étude par mail sur notre site www.beaussant-lefevre.com BEAUSSANT_1_20 6/05/08 15:40 Page 1 LES COURSES et LA CHASSE DOCUMENTATION - GRAVURES - TABLEAUX - SCULPTURES DÉCORATIONS - ARMES - MILITARIA COLLECTION de STATUETTES en bronze de Vienne COLLECTION d’OBJETS à décor tartan VENTE AUX ENCHÈRES PUBLIQUES Le MERCREDI 4 JUIN 2008 à 14 heures Par le Ministère de : Mes Eric BEAUSSANT et Pierre-Yves LEFÈVRE Commissaires-Priseurs BEAUSSANT LEFÈVRE Société de ventes volontaires Siren n° 443 080 338 - Agrément n° 2002-108 32, rue Drouot - 75009 PARIS Tél. : 01 47 70 40 00 - Télécopie : 01 47 70 62 40 www.beaussant-lefevre.com E-mail : [email protected] PARIS - DROUOT RICHELIEU - Salle no 4 9, rue Drouot, 75009 Paris, Tél. : 01 48 00 20 20 - Fax : 01 48 00 20 33 EXPOSITIONS PUBLIQUES : Mardi 3 Juin 2008 de 11 h à 18 h Mercredi 4 Juin 2008 de 11 h à 12 h Téléphone pendant les expositions et la vente : 01 48 00 20 04 En couverture : détail du n° 132 BEAUSSANT_1_20 6/05/08 15:40 Page 2 EXPERTS : Estampes : M.