The History of Rock Music: 1976-1989

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unobtainium-Vol-1.Pdf

Unobtainium [noun] - that which cannot be obtained through the usual channels of commerce Boo-Hooray is proud to present Unobtainium, Vol. 1. For over a decade, we have been committed to the organization, stabilization, and preservation of cultural narratives through archival placement. Today, we continue and expand our mission through the sale of individual items and smaller collections. We invite you to our space in Manhattan’s Chinatown, where we encourage visitors to browse our extensive inventory of rare books, ephemera, archives and collections by appointment or chance. Please direct all inquiries to Daylon ([email protected]). Terms: Usual. Not onerous. All items subject to prior sale. Payment may be made via check, credit card, wire transfer or PayPal. Institutions may be billed accordingly. Shipping is additional and will be billed at cost. Returns will be accepted for any reason within a week of receipt. Please provide advance notice of the return. Please contact us for complete inventories for any and all collections. The Flash, 5 Issues Charles Gatewood, ed. New York and Woodstock: The Flash, 1976-1979. Sizes vary slightly, all at or under 11 ¼ x 16 in. folio. Unpaginated. Each issue in very good condition, minor edgewear. Issues include Vol. 1 no. 1 [not numbered], Vol. 1 no. 4 [not numbered], Vol. 1 Issue 5, Vol. 2 no. 1. and Vol. 2 no. 2. Five issues of underground photographer and artist Charles Gatewood’s irregularly published photography paper. Issues feature work by the Lower East Side counterculture crowd Gatewood associated with, including George W. Gardner, Elaine Mayes, Ramon Muxter, Marcia Resnick, Toby Old, tattooist Spider Webb, author Marco Vassi, and more. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

PATTI SMITH Eighteen Stations MARCH 3 – APRIL 16, 2016

/robertmillergallery For immediate release: [email protected] @RMillerGallery 212.366.4774 /robertmillergallery PATTI SMITH Eighteen Stations MARCH 3 – APRIL 16, 2016 New York, NY – February 17, 2016. Robert Miller Gallery is pleased to announce Eighteen Stations, a special project by Patti Smith. Eighteen Stations revolves around the world of M Train, Smith’s bestselling book released in 2015. M Train chronicles, as Smith describes, “a roadmap to my life,” as told from the seats of the cafés and dwellings she has worked from globally. Reflecting the themes and sensibility of the book, Eighteen Stations is a meditation on the act of artistic creation. It features the artist’s illustrative photographs that accompany the book’s pages, along with works by Smith that speak to art and literature’s potential to offer hope and consolation. The artist will be reading from M Train at the Gallery throughout the run of the exhibition. Patti Smith (b. 1946) has been represented by Robert Miller Gallery since her joint debut with Robert Mapplethorpe, Film and Stills, opened at its 724 Fifth Avenue location in 1978. Recent solo exhibitions at the Gallery include Veil (2009) and A Pythagorean Traveler (2006). In 2014 Rockaway Artist Alliance and MoMA PS1 mounted Patti Smith: Resilience of the Dreamer at Fort Tilden, as part of a special project recognizing the ongoing recovery of the Rockaway Peninsula, where the artist has a home. Smith's work has been the subject of solo exhibitions at institutions worldwide including the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto (2013); Detroit Institute of Arts (2012); Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford (2011); Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporaine, Paris (2008); Haus der Kunst, Munich (2003); and The Andy Warhol Museum (2002). -

The Rolling Stones and Performance of Authenticity

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies Art & Visual Studies 2017 FROM BLUES TO THE NY DOLLS: THE ROLLING STONES AND PERFORMANCE OF AUTHENTICITY Mariia Spirina University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2017.135 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Spirina, Mariia, "FROM BLUES TO THE NY DOLLS: THE ROLLING STONES AND PERFORMANCE OF AUTHENTICITY" (2017). Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies. 13. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/art_etds/13 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Art & Visual Studies at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Art to Commerce: the Trajectory of Popular Music Criticism

Art to Commerce: The Trajectory of Popular Music Criticism Thomas Conner and Steve Jones University of Illinois at Chicago [email protected] / [email protected] Abstract This article reports the results of a content and textual analysis of popular music criticism from the 1960s to the 2000s to discern the extent to which criticism has shifted focus from matters of music to matters of business. In part, we believe such a shift to be due likely to increased awareness among journalists and fans of the industrial nature of popular music production, distribution and consumption, and to the disruption of the music industry that began in the late 1990s with the widespread use of the Internet for file sharing. Searching and sorting the Rock’s Backpages database of over 22,000 pieces of music journalism for keywords associated with the business, economics and commercial aspects of popular music, we found several periods during which popular music criticism’s focus on business-related concerns seemed to have increased. The article discusses possible reasons for the increases as well as methods for analyzing a large corpus of popular music criticism texts. Keywords: music journalism, popular music criticism, rock criticism, Rock’s Backpages Though scant scholarship directly addresses this subject, music journalists and bloggers have identified a trend in recent years toward commerce-specific framing when writing about artists, recording and performance. Most music journalists, according to Willoughby (2011), “are writing quasi shareholder reports that chart the movements of artists’ commercial careers” instead of artistic criticism. While there may be many reasons for such a trend, such as the Internet’s rise to prominence not only as a medium for distribution of music but also as a medium for distribution of information about music, might it be possible to discern such a trend? Our goal with the research reported here was an attempt to empirically determine whether such a trend exists and, if so, the extent to which it does. -

Ramones 2002.Pdf

PERFORMERS THE RAMONES B y DR. DONNA GAINES IN THE DARK AGES THAT PRECEDED THE RAMONES, black leather motorcycle jackets and Keds (Ameri fans were shut out, reduced to the role of passive can-made sneakers only), the Ramones incited a spectator. In the early 1970s, boredom inherited the sneering cultural insurrection. In 1976 they re earth: The airwaves were ruled by crotchety old di corded their eponymous first album in seventeen nosaurs; rock & roll had become an alienated labor - days for 16,400. At a time when superstars were rock, detached from its roots. Gone were the sounds demanding upwards of half a million, the Ramones of youthful angst, exuberance, sexuality and misrule. democratized rock & ro|ft|you didn’t need a fat con The spirit of rock & roll was beaten back, the glorious tract, great looks, expensive clothes or the skills of legacy handed down to us in doo-wop, Chuck Berry, Clapton. You just had to follow Joey’s credo: “Do it the British Invasion and surf music lost. If you were from the heart and follow your instincts.” More than an average American kid hanging out in your room twenty-five years later - after the band officially playing guitar, hoping to start a band, how could you broke up - from Old Hanoi to East Berlin, kids in full possibly compete with elaborate guitar solos, expen Ramones regalia incorporate the commando spirit sive equipment and million-dollar stage shows? It all of DIY, do it yourself. seemed out of reach. And then, in 1974, a uniformed According to Joey, the chorus in “Blitzkrieg Bop” - militia burst forth from Forest Hills, Queens, firing a “Hey ho, let’s go” - was “the battle cry that sounded shot heard round the world. -

Drone Music from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Drone music From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Drone music Stylistic origins Indian classical music Experimental music[1] Minimalist music[2] 1960s experimental rock[3] Typical instruments Electronic musical instruments,guitars, string instruments, electronic postproduction equipment Mainstream popularity Low, mainly in ambient, metaland electronic music fanbases Fusion genres Drone metal (alias Drone doom) Drone music is a minimalist musical style[2] that emphasizes the use of sustained or repeated sounds, notes, or tone-clusters – called drones. It is typically characterized by lengthy audio programs with relatively slight harmonic variations throughout each piece compared to other musics. La Monte Young, one of its 1960s originators, defined it in 2000 as "the sustained tone branch of minimalism".[4] Drone music[5][6] is also known as drone-based music,[7] drone ambient[8] or ambient drone,[9] dronescape[10] or the modern alias dronology,[11] and often simply as drone. Explorers of drone music since the 1960s have included Theater of Eternal Music (aka The Dream Syndicate: La Monte Young, Marian Zazeela, Tony Conrad, Angus Maclise, John Cale, et al.), Charlemagne Palestine, Eliane Radigue, Philip Glass, Kraftwerk, Klaus Schulze, Tangerine Dream, Sonic Youth,Band of Susans, The Velvet Underground, Robert Fripp & Brian Eno, Steven Wilson, Phill Niblock, Michael Waller, David First, Kyle Bobby Dunn, Robert Rich, Steve Roach, Earth, Rhys Chatham, Coil, If Thousands, John Cage, Labradford, Lawrence Chandler, Stars of the Lid, Lattice, -

Exposing Corruption in Progressive Rock: a Semiotic Analysis of Gentle Giant’S the Power and the Glory

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2019 EXPOSING CORRUPTION IN PROGRESSIVE ROCK: A SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF GENTLE GIANT’S THE POWER AND THE GLORY Robert Jacob Sivy University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2019.459 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Sivy, Robert Jacob, "EXPOSING CORRUPTION IN PROGRESSIVE ROCK: A SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF GENTLE GIANT’S THE POWER AND THE GLORY" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 149. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/149 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

PUNK/ASKĒSIS by Robert Kenneth Richardson a Dissertation

PUNK/ASKĒSIS By Robert Kenneth Richardson A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY Program in American Studies MAY 2014 © Copyright by Robert Richardson, 2014 All Rights Reserved © Copyright by Robert Richardson, 2014 All Rights Reserved To the Faculty of Washington State University: The members of the Committee appointed to examine the dissertation of Robert Richardson find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. ___________________________________ Carol Siegel, Ph.D., Chair ___________________________________ Thomas Vernon Reed, Ph.D. ___________________________________ Kristin Arola, Ph.D. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS “Laws are like sausages,” Otto von Bismarck once famously said. “It is better not to see them being made.” To laws and sausages, I would add the dissertation. But, they do get made. I am grateful for the support and guidance I have received during this process from Carol Siegel, my chair and friend, who continues to inspire me with her deep sense of humanity, her astute insights into a broad range of academic theory and her relentless commitment through her life and work to making what can only be described as a profoundly positive contribution to the nurturing and nourishing of young talent. I would also like to thank T.V. Reed who, as the Director of American Studies, was instrumental in my ending up in this program in the first place and Kristin Arola who, without hesitation or reservation, kindly agreed to sign on to the committee at T.V.’s request, and who very quickly put me on to a piece of theory that would became one of the analytical cornerstones of this work and my thinking about it. -

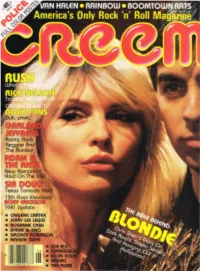

RUSH: but WHY ARE THEY in SUCH a HURRY? What to Do When the Snow-Dog Bites! •••.•.••••..•....••...••••••.•.•••...•.•.•..•

• CARLENE CARTER • JERRY LEE LEWIS • ROSANNE CASH • BYRNE & ENO • SMOKEY acMlNSON • MARVIN GAYE THE SONG OF INJUN ADAM Or What's A Picnic Without Ants? .•.•.•••••..•.•.••..•••••.••.•••..••••••.•••••.•••.•••••. 18 tight music by brit people by Chris Salewicz WHAT YEAR DID YOU SAY THIS WAS? Hippie Happiness From Sir Doug ....••..•..••..•.••••••••.•.••••••••••••.••••..•...•.••.. 20 tequila feeler by Toby Goldstein BIG CLAY PIGEONS WITH A MIND OF THEIR OWN The CREEM Guide To Rock Fans ••.•••••••••••••••••••.•.••.•••••••.••••.•..•.•••••••••. 22 nebulous manhood displayed by Rick Johnson HOUDINI IN DREADLOCKS . Garland Jeffreys' Newest Slight-Of-Sound •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••.••..••. 24 no 'fro pick. no cry by Toby Goldstein BLONDIE IN L.A. And Now For Something Different ••••.••..•.••.••.•.•••..••••••••••.••••.••••••.••..••••• 25 actual wri ting by Blondie's Chris Stein THE PSYCHEDELIC SOUNDS OF ROKY EmCKSON , A Cold Night For Elevators •••.••.•••••.•••••••••.••••••••.••.••.•••..••.••.•.•.••.•••.••.••. 30 fangs for the memo ries by Gregg Turner RUSH: BUT WHY ARE THEY IN SUCH A HURRY? What To Do When The Snow-Dog Bites! •••.•.••••..•....••...••••••.•.•••...•.•.•..•. 32 mortgage payments mailed out by J . Kordosh POLICE POSTER & CALENDAR •••.•••.•..••••••••••..•••.••.••••••.•••.•.••.••.••.••..•. 34 LONESOME TOWN CHEERS UP Rick Nelson Goes Back On The Boards .•••.••••••..•••••••.••.•••••••••.••.••••••.•.•.. 42 extremely enthusiastic obsewations by Susan Whitall UNSUNG HEROES OF ROCK 'N' ROLL: ELLA MAE MORSE .••.••••.•..•••.••.• 48 control -

Rhino Reissues the Ramones' First Four Albums

2011-07-11 09:13 CEST Rhino Reissues The Ramones’ First Four Albums NOW I WANNA SNIFF SOME WAX Rhino Reissues The Ramones’ First Four Albums Both Versions Available July 19 Hey, ho, let’s go. Rhino celebrates the Ramones’ indelible musical legacy with reissues of the pioneering group’s first four albums on 180-gram vinyl. Ramones, Leave Home, Rocket To Russia and Road To Ruin look amazing and come in accurate reproductions of the original packaging. More importantly, the records sound magnificent and were made using lacquers cut from the original analog masters by Chris Bellman at Bernie Grundman Mastering. For these releases, Rhino will – for the first time ever on vinyl – reissue the first pressing of Leave Home, which includes “Carbona Not Glue,” a track that was replaced with “Sheena Is A Punk Rocker” on all subsequent pressings. Joey, Johnny, Dee Dee and Tommy Ramone. The original line-up – along with Marky Ramone who joined in 1978 – helped blaze a trail more than 30 years ago with this classic four-album run. It’s hard to overstate how influential the group’s signature sound – minimalist rock played at maximum volume – was at the time, and still is today. These four landmark albums – Ramones (1976), Leave Home (1977), Rocket To Russia (1977) and Road to Ruin (1978) – contain such unforgettable songs as: “Blitzkrieg Bop,” “Sheena Is Punk Rocker,” “Beat On The Brat,” “Now I Wanna Sniff Some Glue,” “Pinhead,” “Rockaway Beach” and “I Wanna Be Sedated.” RAMONES Side One Side Two 1. “Blitzkrieg Bop” 1. “Loudmouth” 2. “Beat On The Brat” 2. -

Televisions Marquee Moon Free

FREE TELEVISIONS MARQUEE MOON PDF Bryan Waterman | 144 pages | 27 Jul 2011 | Continuum Publishing Corporation | 9781441186058 | English | New York, United States Marquee Moon - Television | Songs, Reviews, Credits | AllMusic Television, St. Marks Place, New York City, The goal was to create something simpler, more caustic, the very antithesis of anything beyond three chords and the truth. Otherwise, the record fits in equally well with the Soho free-jazz loft scene as it does with the gyrating punk of CBGB. When I teach students, I teach them to play more like themselves. Both of them are gone, and all I have is the memories. But Television were not Televisions Marquee Moon that. We were punctual. And Televisions Marquee Moon. What kind of trip is this? Tom Verlaine. So Andy came up with Televisions Marquee Moon idea. He nearly took my fucking nose off. I was backing up while I was playing. The risks Johns and Televisions Marquee Moon band took in the studio paid off. We get it: you like to have control of your own internet experience. But advertising revenue helps support our journalism. To read our full stories, please turn off your ad blocker. We'd really appreciate it. Click the AdBlock button on your browser and select Don't run on pages on this domain. How Do I Whitelist Observer? Below are steps you can take in order to whitelist Observer. Then Reload the Page. Letra de la canción Marquee Moon - Television More Images. Please enable Javascript to take full advantage of our site features. Edit Master Release. New WavePunk.