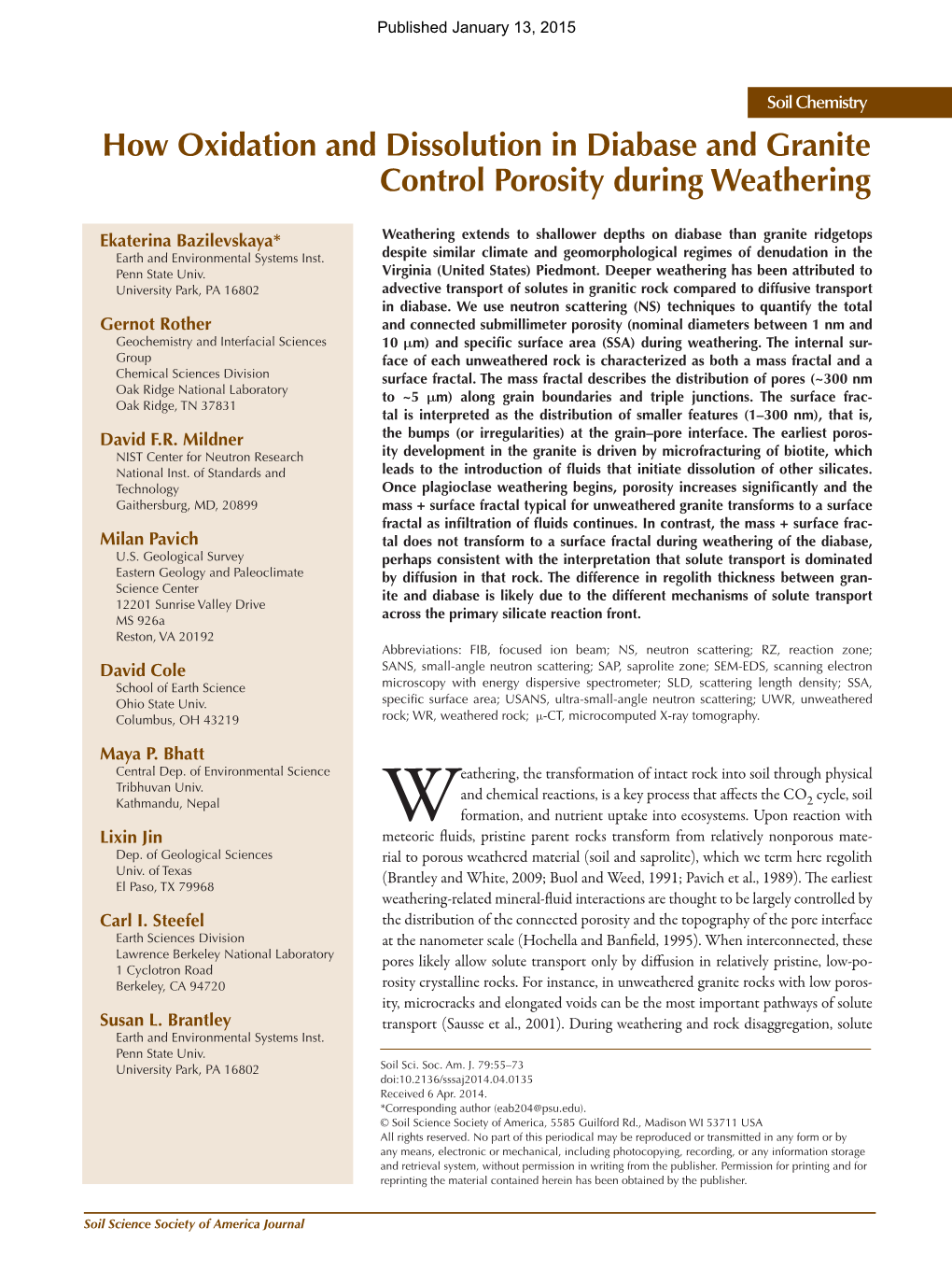

How Oxidation and Dissolution in Diabase and Granite Control Porosity During Weathering

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Source and Bedrock Distribution of Gold and Platinum-Group Metals in the Slate Creek Area, Northern.Chistochina Mining District, East-Central Alaska

Source and Bedrock Distribution of Gold and Platinum-Group Metals in the Slate Creek Area, Northern.Chistochina Mining District, East-Central Alaska By: Jeffrey Y. Foley and Cathy A. Summers Open-file report 14-90******************************************1990 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Manuel Lujan, Jr., Secretary BUREAU OF MINES T S Arv. Director TN 23 .U44 90-14 c.3 UNITED STATES BUREAU OF MINES -~ ~ . 4,~~~~1 JAMES BOYD MEMORIAL LIBRARY CONTENTS Abstract 1 Introduction 2 Acknowledgments 2 Location, access, and land status 2 History and production 4 Previous work 8 Geology 8 Regional and structural geologic setting 8 Rock units 8 Dacite stocks, dikes, and sills 8 Limestone 9 Argillite and sandstone 9 Differentiated igneous rocks north of the Slate Creek Fault Zone 10 Granitic rocks 16 Tertiary conglomerate 16 Geochemistry and metallurgy 18 Mineralogy 36 Discussion 44 Recommendations 45 References 47 ILLUSTRATIONS 1. Map of Slate Creek and surrounding area, in the northern Chistochina Mining District 3 2. Geologic map of the Slate Creek area, showing sample localities and cross section (in pocket) 3. North-dipping slaty argillite with lighter-colored sandstone intervals in lower Miller Gulch 10 4. North-dipping differentiated mafic and ultramafic sill capping ridge and overlying slaty argillite at upper Slate Creek 11 5. Dike swarm cutting Jurassic-Cretaceous turbidites in Miller Gulch 12 6 60-ft-wide diorite porphyry and syenodiorite porphyry dike at Miller Gulch 13 7. Map showing the locations of PGM-bearing mafic and ultramafic rocks and major faults in the east-central Alaska Range 14 8. Major oxides versus Thornton-Tuttle differentiation index 17 9. -

Geochemical Analysis of Beaver River Diabase in Comparison to Anorthosite Inclusions and Similar Mid- Continental Rift Diabase

GEOCHEMICAL ANALYSIS OF BEAVER RIVER DIABASE IN COMPARISON TO ANORTHOSITE INCLUSIONS AND SIMILAR MID- CONTINENTAL RIFT DIABASE Jenna Fischer NDSU Petrology Dr. Saini- Eidukat 5/3/16 BACKGROUND MID- CONTINENT RIFT SYSTEM • Also known as Keweenawan Rift • Middle Proterozoic in age: ~ 1.1 Ga • Triple- junction rift that extends into Kansas and the lower peninsula of Michigan • Outcrops from the MRS are only seen around the Lake Superior region • Generally composed of flood basalts and intrusions • Source was a mantle plume • End of MRS could be Grenvillian orogeny (debatable) Image: www.earthscope.org Miller (1997) LAKE SUPERIOR REGION • Many intrusions in comparison to volcanic rock (60%) • Types of intrusions: Troctolitic, gabbroic, anorthositic, and granitic • Duluth Complex, North Shore Volcanic Group, and Hypabyssal Intrusions • Most hypabyssal intrusions are younger than Duluth Complex • Transitional boundary between complexes • Faults Green (1972) Miller (1997) Map: Miller and Green (2002) LAKE SUPERIOR REGION Map: Miller and Green (2002) HYPABYSSAL INTRUSIONS • Definition: a sub-volcanic rock; an intrusive igneous rock that is emplaced at medium to shallow depth within the crust between volcanic and plutonic • Largest concentration of these subvolcanic intrusions forms the Beaver Bay Complex • Whole rock compositions approximate the magma compositions • Most hypabyssal intrusions do not display igneous foliation and lack signs of differentiation • But late intrusions do! Ex. Sonju Lake, Beaver River Diabase Miller and Green (2002) -

Structure and Petrology of the Deer Peaks Area Western North Cascades, Washington

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Winter 1986 Structure and Petrology of the Deer Peaks Area Western North Cascades, Washington Gregory Joseph Reller Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the Geology Commons Recommended Citation Reller, Gregory Joseph, "Structure and Petrology of the Deer Peaks Area Western North Cascades, Washington" (1986). WWU Graduate School Collection. 726. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/726 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STRUCTURE AMD PETROLOGY OF THE DEER PEAKS AREA iVESTERN NORTH CASCADES, WASHIMGTa^ by Gregory Joseph Re Her Accepted in Partial Completion of the Requiremerjts for the Degree Master of Science February, 1986 School Advisory Comiiattee STRUCTURE AiO PETROIDGY OF THE DEER PEAKS AREA WESTERN NORTIi CASCADES, VC'oHINGTON A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Western Washington University In Partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree Master of Science by Gregory Joseph Re Her February, 1986 ABSTRACT Dominant bedrock mits of the Deer Peaks area, nortliv/estern Washington, include the Shiaksan Metamorphic Suite, the Deer Peaks unit, the Chuckanut Fontation, the Oso volcanic rocks and the Granite Lake Stock. Rocks of the Shuksan Metainorphic Suite (SMS) exhibit a stratigraphy of meta-basalt, iron/manganese schist, and carbonaceous phyllite. Tne shear sense of stretching lineations in the SMS indicates that dioring high pressure metamorphism ttie subduction zone dipped to the northeast relative to the present position of the rocks. -

Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Tasmania Open Access Repository ON MESOZOIC DOLERITP] AND DIABASE IN TASMANIA. By W. H. Twblvetrees, F.G.S., and W. F. Petterd, C.M.Z.S. The following Notes lay no claim to be an exhaustive description of our familiar '• diabase" or "dolerite" rock, which plays such an important part in the geology and physical configuration of our Island. The present object is rather to place upon record some inferences drawn from the examination of numerous microscopical sections of speci- mens collected or received from all parts of Tasmania. It is by accumulating the results of observations that stepping stones are formed to more complete knowledge. A glance at Mr. R. M. Johnston's geological map of Tasmania, issued by the Lands Office, will show the share this rock takes in the structure of the Island. It occupies the whole upland area of the Central Tiers. On the northern face of the Tiers—the Western Tiers as they are here called—there is a tongue of the rock prolonged northwards past IMount Claude. At their north-west corner it forms or caps mountains, such as Cradle Mountain (the highest in Tas- mania), Barn Bluff, Mount Pelion West. Eldon Blufi: forms a narrow western extension. Mount Sedgwick is a western out-lier ; Mount Dundas another. In that part of the island it is also found at Mount Heemskirk Falls, and on the Magnet Range, two miles north of the Magnet Mine. Mounts Gell and Hugel are also western out-liers. -

Oregon Geologic Digital Compilation Rules for Lithology Merge Information Entry

State of Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries Vicki S. McConnell, State Geologist OREGON GEOLOGIC DIGITAL COMPILATION RULES FOR LITHOLOGY MERGE INFORMATION ENTRY G E O L O G Y F A N O D T N M I E N M E T R R A A L P I E N D D U N S O T G R E I R E S O 1937 2006 Revisions: Feburary 2, 2005 January 1, 2006 NOTICE The Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries is publishing this paper because the infor- mation furthers the mission of the Department. To facilitate timely distribution of the information, this report is published as received from the authors and has not been edited to our usual standards. Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries Oregon Geologic Digital Compilation Published in conformance with ORS 516.030 For copies of this publication or other information about Oregon’s geology and natural resources, contact: Nature of the Northwest Information Center 800 NE Oregon Street #5 Portland, Oregon 97232 (971) 673-1555 http://www.naturenw.org Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries - Oregon Geologic Digital Compilation i RULES FOR LITHOLOGY MERGE INFORMATION ENTRY The lithology merge unit contains 5 parts, separated by periods: Major characteristic.Lithology.Layering.Crystals/Grains.Engineering Lithology Merge Unit label (Lith_Mrg_U field in GIS polygon file): major_characteristic.LITHOLOGY.Layering.Crystals/Grains.Engineering major characteristic - lower case, places the unit into a general category .LITHOLOGY - in upper case, generally the compositional/common chemical lithologic name(s) -

Komatiites of the Weltevreden Formation, Barberton Greenstone

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 Komatiites of the Weltevreden Formation, Barberton Greenstone Belt, South Africa: implications for the chemistry and temperature of the Archean mantle Keena Kareem Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Earth Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Kareem, Keena, "Komatiites of the Weltevreden Formation, Barberton Greenstone Belt, South Africa: implications for the chemistry and temperature of the Archean mantle" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3249. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3249 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. KOMATIITES OF THE WELTEVREDEN FORMATION, BARBERTON GREENSTONE BELT, SOUTH AFRICA: IMPLICATIONS FOR THE CHEMISTRY AND TEMPERATURE OF THE ARCHEAN MANTLE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Geology and Geophysics by Keena Kareem B.S., Tulane University, 1999 May 2005 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author wishes to thank, Dr. Gary Byerly, the author’s major advisor for guidance and support in defining the project, technical assistance with instrumentation, and practical advice concerning non-dissertation related issues. Appreciation goes out to the other members of the advisory committee: Drs. Huiming Bao, Lui-Heung Chan, Ray Ferrell, Darrell Henry, of the Department of Geology and Geophysics, and Dr. -

The Metamorphism of the Cambrian Basic Volcanic Rocks of Tasmania and Its Relationship to the Geosynclinal Environ Ment

PAPlilllS AND PROCEEDINGS OF THE ROYAL SOCI>lTY OF TASMANIA, VOLUMB 88 The Metamorphism of the Cambrian Basic Volcanic Rocks of Tasmania and its Relationship to the Geosynclinal Environ ment By BERYL SCOTT, B.SC., PH.D. (With 4 Plates and 2 Text Ji'igwres) ABSTRACT A spilitic suite comprising picrite basalts, spilites, keratophyres, albite dolerites and associated pyroclastics of Middle and Upper Cambrian age, outcrops on the North-Vi/est and West Coast of Tasmania. The spilites and keratophyres are considered to have been normal basalts which later suffered soda metasomatism as a result of geosynclinal depOl::,ition and orogeny. Hydrothermal alteration of the volcanics has also given rise to a variety of other rock types which includes porphyries, variolite, spherulitic quartz rock and jasper. INTRODlJCTION While the author was resident in Tasmania, a detailed petrographie study was made of the Cambrian volcanle rocks of the State and the results were submitted to the University of Tasmania as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in 1952. Several papers have already been published on this work (Scott, 1952), but after leaving Tasmania it was thought necessary to publish a general summary of the whole study even though the interpretations may not be eonelusive. Mueh confusion exists in the literature dealing with the volcanics of the 'Vest Coast of Tasmania. The igneous rocks have been referred to as porphyroids, keratophyres, quartz and feldspar porphyries, andesites, melaphyres and syenites. The present author believes that the greater part of the volcanics was essentially basic in composition, probably basalts and porphyritic basalts, with or without amygdales, and their corresponding pyroclastics. -

A Partial Glossary of Spanish Geological Terms Exclusive of Most Cognates

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY A Partial Glossary of Spanish Geological Terms Exclusive of Most Cognates by Keith R. Long Open-File Report 91-0579 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards or with the North American Stratigraphic Code. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. 1991 Preface In recent years, almost all countries in Latin America have adopted democratic political systems and liberal economic policies. The resulting favorable investment climate has spurred a new wave of North American investment in Latin American mineral resources and has improved cooperation between geoscience organizations on both continents. The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) has responded to the new situation through cooperative mineral resource investigations with a number of countries in Latin America. These activities are now being coordinated by the USGS's Center for Inter-American Mineral Resource Investigations (CIMRI), recently established in Tucson, Arizona. In the course of CIMRI's work, we have found a need for a compilation of Spanish geological and mining terminology that goes beyond the few Spanish-English geological dictionaries available. Even geologists who are fluent in Spanish often encounter local terminology oijerga that is unfamiliar. These terms, which have grown out of five centuries of mining tradition in Latin America, and frequently draw on native languages, usually cannot be found in standard dictionaries. There are, of course, many geological terms which can be recognized even by geologists who speak little or no Spanish. -

Originally Published As: Hewawasam, T., Von

Originally published as: Hewawasam, T., von Blanckenburg, F., Bouchez, J., Dixon, J. L., Schuessler, J. A., Maekeler, R. (2013): Slow advance of the weathering front during deep, supply‐limited saprolite formation in the tropical Highlands of Sri Lanka. ‐ Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 118, 1, 202‐230 DOI: 10.1016/j.gca.2013.05.006 Slow advance of the weathering front during deep, supply-limited saprolite formation in the tropical Highlands of Sri Lanka Tilak Hewawasam1*, Friedhelm von Blanckenburg2, Julien Bouchez2, Jean L. Dixon2, Jan A. Schuessler2, Ricarda Maekeler2,3 1Department of Natural Resources, Sabaragamuwa University of Sri Lanka, Belihuloya, Sri Lanka, [email protected]. 2GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences, Section 3.4, Earth Surface Geochemistry, Telegrafenberg, 14473 Potsdam, Germany [email protected] 3 DFGGraduate School 1364 at Institute of Geosciences, University of Potsdam, Germany Geochimica Cosmochmica Acta 2013 doi:10.1016/j.gca.2013.05.006 Abstract Silicate weathering – initiated by major mineralogical transformations at the base of ten meters of clay- rich saprolite – generates the exceptionally low weathering flux found in streams draining the crystalline rocks of the mountainous and humid tropical Highlands of Sri Lanka. This conclusion is reached from a thorough investigation of the mineralogical, chemical, and Sr isotope compositions of samples within a regolith profile extending >10 m from surface soil through the weathering front in charnockite bedrock (a high-grade metamorphic rock), corestones formed at the weathering front, as well as from the chemical composition of the dissolved loads in nearby streams. Weatherable minerals and soluble elements are fully depleted at the top of the profile, showing that the system is supply-limited, such that weathering fluxes are controlled directly by the supply of fresh minerals. -

Weathering Front.Pdf

Earth-Science Reviews 198 (2019) 102925 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Earth-Science Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/earscirev Weathering fronts T ⁎ Jonathan D. Phillipsa,c, , Łukasz Pawlikb, Pavel Šamonilc a Earth Surface Systems Program, Department of Geography, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY 40508, USA b Faculty of Earth Sciences, University of Silesia, ul. Będzińska 60, 41-200 Sosnowiec, Poland c The Silva Tarouca Research Institute, Department of Forest Ecology, Lidická 25/27, Brno 602 00, Czech Republic ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: A distinct boundary between unweathered and weathered rock that moves downward as weathering pro- Weathering profile ceeds—the weathering front—is explicitly or implicitly part of landscape evolution concepts of etchplanation, Regolith triple planation, dynamic denudation, and weathering- and supply-limited landscapes. Weathering fronts also fl Multidirectional mass uxes figure prominently in many models of soil, hillslope, and landscape evolution, and mass movements. Clear Critical zone transitions from weathered to unweathered material, increasing alteration from underlying bedrock to the Soil evolution surface, and lateral continuity of weathering fronts are ideal or benchmark conditions. Weathered to un- Hillslope processes weathered transitions are often gradual, and weathering fronts may be geometrically complex. Some weathering profiles contain pockets of unweathered rock, and highly modified and unmodified parent material at similar depths in close proximity. They also reflect mass fluxes that are more varied than downward-percolating water and slope-parallel surface processes. Fluxes may also be upward, or lateral along lithological boundaries, structural features, and textural or weathering-related boundaries. Fluxes associated with roots, root channels, and faunal burrows may potentially occur in any direction. -

GMS 18-2, Geologic Map of the New Jersey Portion of the Lumberville

DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION Prepared in cooperation with the GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE NEW JERSEY PORTION WATER RESOURCES MANAGEMENT U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF THE LUMBERVILLE QUADRANGLE NEW JERSEY GEOLOGICAL AND WATER SURVEY NATIONAL GEOLOGIC MAPPING PROGRAM HUNTERDON COUNTY, NEW JERSEY GEOLOGIC MAP SERIES GMS 18-2 N FRENCHTOWN PITTSTOWN 75o05’00 75o02’0 75o00’ o o 0 0’00 A 0 0’00 Contour Plot ately sorted, weakly stratified. Deposits along Lockatong Creek are chiefly flag- 8 5 7 8 7 INTRODUCTION CORRELATION OF MAP UNITS Qe p Qal p 9 D F Fishing 6 8 p 16 R 200 7 4 D stone gravel composed of gray and red mudstone, with a matrix of reddish-brown FARM Qcs 8 11 14 L RD 8 4 40 R 12 The Lumberville 7.5-minute topographic quadrangle lies within the Piedmont R 300 L Island Qw 4 8 10 Qcal 10 Qcal 0 p Qcal E U Qst 4 N 10 to grayish-brown silt, and are generally less than 10 feet thick. They form terraces H 50 M S 5 0 O 6 SURFICIAL 2 8 I physiographic province, Hunterdon County, west central New Jersey and Bucks E 300 Qal 5 6 HO 4 6 R N 5 to 10 feet above the modern floodplain and are likely of late Wisconsinan age. T Qcal SES Percent D T 10 H U R O 500 per 1% area County, Pennsylvania. The region has not succumbed to the “growing” pressures E Qcal pg E p K T 9 B Deposits along the Delaware River are chiefly yellowish-brown silt and fine sand L 6 5 E Qcal Qal A Holocene N 5 10 15 from suburban development and continues to maintain a rural character. -

Principles and Dynamics of the Critical Zone

Developments in Earth Surface Processes Volume 19 Principles and Dynamics of the Critical Zone Edited by John R. Giardino Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA Chris Houser Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA !-34%2$!-s"/34/.s(%)$%,"%2's,/.$/. .%79/2+s/8&/2$0!2)3s3!.$)%'/ 3!.&2!.#)3#/s3).'!0/2%s39$.%9s4/+9/ #HAPTER Regolith and Weathering (Rock Decay) in the Critical Zone Gregory A. Pope Department of Earth and Environmental Studies, Montclair State University, Montclair, New Jersey, USA 4.1 INTRODUCTION Weathering and the Critical Zone have been inextricably linked, as both nested process domains in Earth history, and as much more recent research priorities among environmental scientists. The United States National Research Coun- cil’s (USNRC) (2001) report defined the Critical Zone as the “heterogeneous, near-surface environment in which complex interactions involving rock, soil, water, air and living organisms regulate the natural habitat and determine avail- ability of life-sustaining resources.” This is commonly identified as “the frag- ile skin of the planet defined from the outer extent of vegetation down to the lower limits of groundwater” (Brantley et al., 2007, p. 307). Shortly following the USNRC report, a collaborating body of Earth scientists initiated what was then called the Weathering Systems Science Consortium (WSSC) (Anderson et al., 2004), intent on studying “Earth’s weathering engine” in the context of the Critical Zone. The WSSC evolved into a more-encompassing Critical Zone Exploration Network (CZEN) as the collaboration involved more ecologists, hydrologists, and pedologists less intent on examining the weathering engine.