The Independent Counsel Law: Is There Life After Death?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Katz •Fi Variations on a Theme by Berger

Catholic University Law Review Volume 17 Issue 3 Article 4 1968 Katz – Variations on a Theme by Berger Samuel Dash Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation Samuel Dash, Katz – Variations on a Theme by Berger, 17 Cath. U. L. Rev. 296 (1968). Available at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview/vol17/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Catholic University Law Review by an authorized editor of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Katz-Variations on a Theme by Berger SAMUEL DASH* Introduction Nearly forty years of controversy concerning government electronic eaves- dropping on private conversations apparently was settled last year when the Supreme Court decided Berger v. New York' and Katz v. United States.2 The effect of these decisions locks both government electronic bugging and wiretapping practices within the requirements of the search and seizure provisions of the fourth amendment of the United States Constitution. Berger specifically held unconstitutional a New York statute authorizing court-ordered electronic eavesdropping on private conversations, on the ground that it did not require adherence to the appropriate standards or limitations compelled by the search and seizure provisions of the fourth amendment. The Court emphasized that the statute's outstanding omission was its failure to maintain adequate probable cause standards for judicial review of an eavesdropping application. The requirement of a specific description of the conversation to be overheard was a standard particularly found lacking. -

![Samuel Dash Papers [Finding Aid]. Manuscript Division, Library of Congress](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4626/samuel-dash-papers-finding-aid-manuscript-division-library-of-congress-244626.webp)

Samuel Dash Papers [Finding Aid]. Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

Samuel Dash Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2009 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Catalog Record: https://lccn.loc.gov/mm2005085201 Additional search options available at: https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms010147 Prepared by Melinda K. Friend with the assistance of Daniel Oleksiw, Kimbery L. Owens, and Karen A. Stuart Finding aid encoded by Library of Congress Manuscript Division, 2009 Collection Summary Title: Samuel Dash Papers Span Dates: 1748-2004 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1965-2002) ID No.: MSS85201 Creator: Dash, Samuel Extent: 87,000 items Extent: 253 containers plus 2 classified Extent: 101 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. LC Catalog record: https://lccn.loc.gov/mm2005085201 Summary: Lawyer, educator, and author. Correspondence, memoranda, legal material and opinions, writings, speeches, engagement file, teaching file, organization and committee file, clippings, photographs, appointment calendars, and other papers relating primarily to Dash's legal career after 1964, and more particularly his role in governmental investigations. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the LC Catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically. People Clinton, Bill, 1946- Clinton, Bill, 1946- --Friends and associates. Clinton, Hillary Rodham. Curran, James J.--Trials, litigation, etc. Dash, Samuel. Dash, Samuel. Intruders : unreasonable searches and seizures from King John to John Ashcroft. 2004. Dash, Samuel. Justice denied : a challenge to Lord Widgery's report on Bloody Sunday. -

Barr Will Not Be Independent of President Trump Or

Attorney General Nominee William barr President Trump announced that he intends to nominate William Barr to be attorney general. Barr served as attorney general under President George H.W. Bush from 1991-1993. Since then, he has been a telecommunications executive and board member, as well as in private legal practice. BARR WILL NOT BE INDEPENDENT OF PRESIDENT TRUMP OR RESTRAIN Trump’s ATTACKS ON THE RULE OF LAW Threat TO THE MUELLER INVESTIGATION Barr authored a controversial memo attacking part of the Mueller investigation. In June 2018, Barr sent the Department of Justice a lengthy memo arguing that Mueller shouldn't be able to investigate Trump for obstruction of justice. The memo, which Barr reportedly shared with the White House as well, raises serious concerns that Barr thinks Trump should be above the law. Barr has already been asked to defend President Trump in the Mueller investigation. President Trump repeatedly criticized Attorney General Jeff Sessions for failing to rein in Special Counsel Robert Mueller, and clearly a priority for the president is appointing an individual to lead the Justice Department who will protect him from investigations. President Trump has reportedly asked Barr in the past whether he would serve as Trump’s personal defense attorney and has inquired whether Barr, like Sessions, would recuse himself from the Mueller investigation. Barr is already on record minimizing the seriousness of allegations surrounding Trump and Russia. In reference to a supposed Clinton uranium scandal that gained traction in right-wing conspiracy circles, it was reported that “Mr. Barr said he sees more basis for investigating the uranium deal than any supposed collusion between Mr. -

Independent Counsel Investigations During the Reagan Administration

Reagan Library – Independent Counsel Investigations during the Reagan Administration This Reagan Library topic guide contains a description of each Independent Counsel investigation during the Reagan Administration. “See also” references are listed with each description.. The Library has a White House Counsel Investigations collection with series for all of these investigations, and often has a specific topic guide for each investigation. Links to both types of related material is included here. INDEPENDENT COUNSEL INVESTIGATIONS DURING THE REAGAN ADMINISTRATION: INDEPENDENT COUNSEL INVESTIGATION OF SECRETARY OF LABOR RAYMOND DONOVAN Special Prosecutor Leon Silverman Counsel to the President, White House Office of: Investigations, Series II Topic Guide: Investigation of Raymond Donovan During January 1981, the FBI conducted a standard background investigation of Secretary of Labor designate Raymond J. Donovan. Summaries of the investigation were furnished through the Assistant Attorney General's Office of Legislative Affairs, Department of Justice, to the U.S. Senate Committee on Labor and Human Resources, the President Elect’s Transition Office and later to the White House Counsel’s Office. This first report contained some allegations regarding Donovan’s ties to organized crime. Based on this information, his confirmation was held up for several weeks in which Donovan testified in Congress multiple times and vigorously maintained his innocence. He was confirmed as Secretary of Labor on February 4, 1981. Throughout 1981, the Senate Committee -

Presidential Obstruction of Justice

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2018 Presidential Obstruction of Justice Daniel Hemel Eric A. Posner Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Daniel Hemel & Eric Posner, "Presidential Obstruction of Justice," 106 California Law Review 1277 (2018). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Presidential Obstruction of Justice Daniel J. Hemel* & Eric A. Posner** Federal obstruction of justice statutes bar anyone from interfering with official legal proceedings based on a “corrupt” motive. But what about the president of the United States? The president is vested with “executive power,” which includes the power to control federal law enforcement. A possible view is that the statutes do not apply to the president because if they did they would violate the president’s constitutional power. However, we argue that the obstruction of justice statutes are best interpreted to apply to the president, and that the president obstructs justice when his motive for intervening in an investigation is to further personal, pecuniary, or narrowly partisan interests, rather than to advance the public good. A brief tour of presidential scandals indicates that, without anyone noticing it, the law of obstruction of justice has evolved into a major check on presidential power. Introduction .......................................................................................... 1278 I. Analysis ............................................................................................ 1283 A. Obstruction of Justice ........................................................ 1283 1. Actus Reus.................................................................. -

I.:: If You Have Issues Viewing Or Accessing This File Contact Us At

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. - . • . • • -. ; . o • .: . ~, ~'~'~<,.~: .'~• '~ -'-'; ~.g-~, ~'•° :~. ~•~. ,~ :--';'~'"' k" :'-~.C~;',"~.~.:;.*--~;:':.,,:~. °~:::o ,:C~':,.;.; ' .~<';~'~,~','-: .~x:~;-',;'•.-_.~::-:-•.~:,.. - .::..~•~ :: ~":, ': ~ ;~;~.h ~ .... ,.. I'-.." : ~',-:'.V:.-<' ",, .,~" ...... ..,.> .... ........... ........... ,...--:.~,~, :,:,:~ct~'~,~',,::'~-:::,~t::~,.~;:~ . • :~•; i : ~ ::X":~:'t'~!:. : ~ " ~f~ ~z-:-:'~'~ 4: ~.::~,$~.!~-:.}o,-~:~?~,~t.:#, ,,_~::~: ':; ": - ..... ::" %':"":;'~:":'~'~'~[1:.::.:~-.2~ ..... " " ,:-- •~::, "-~- ...... *~-,~"'~ -" .-~,[.-"::~,!-k:-~i., ,:--::~•, -~:~:,::~.>~,'~%Z::~-~','.-.:~:;-:'. '-< "= .... ,..::. : :-.~ :4- [;-:., . ,[4 • .':- .~..:~/:...°:.L:q,.-: -:;~-.-." -" .'.., • , . _ •: ".",,..":&:.~7."•:¢;,':t: ;g';': "4:..',:~::c..~.b.'..'%~ ,:-7, ' ,':~"L~(,), • "':ILL:::,I 'i:d'.'~ "~'," ".°- :! ~..r~ ..,,~:~v.- ~- :. :..--~.-.: "::~:" ..... "7,. -" ':: ,,~. < .4..'.-i~'.; ' ;, t. -...;::. : :.:? ... -:... :~ :;...~..-.-,.:[.- ...-..,~ ...... ;..., ..... • ,..,~,:..:.... ,..: ....... .., . :.,, ..... • ,..:. : .-:,....'!:.). :,- -~, , ,:: ....... ,.- : ....... .: ,,.~.: . , , ., ",,--":. ,::.,,/ : .:. -:..:~', .("i,'~;,':,., ':,: :: ,-'.:: ::i.:: ~:':.,[i: /t. i-' -. • ' ..- .: :' ".- "'. - : ,.-. - _ .~ "~. : '..'.'::-- .; ,.:-'.4.,..-','.. ": ••2,'., '." "' ", 7." -, "'-: ~ "-- -~-. ,,: ".~ ."': '..-" • " . :,, ~',':'.o:'~":~"',: ".-:".."~ ": .7": <,~'..%"::.:%1,.'~.~ :. ". :.,"-;.': '": ..... "..','i~,:- . ,: ~,"..'.'.",:':v: ~ L-~.'--, -

Portico 2006/3

PORTICO 2006/3 UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN TAUBMAN COLLEGE OF ARCHITECTURE + URBAN PLANNING Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS From the Dean .......................................................................................1 Letters .....................................................................................................3 College Update Global Place: practice, politics, and the polis TCAUP Centennial Conference #2 .....................................................4 <<PAUSE>> TCAUP@100 .....................................................................6 Centennial Conference #1 ................................................................7 Student Blowout ................................................................................8 Centennial Gala Dinner ....................................................................9 Faculty Update.....................................................................................10 Honor Roll of Donors ..........................................................................16 Alumni Giving by Class Year ..............................................................22 GOLD Gifts (Grads of the Last Decade) ...........................................26 Monteith Society, Gifts in memory of, Gifts in honor of ................27 Campaign Update................................................................................27 Honor Roll of Volunteers ....................................................................28 Class Notes ..........................................................................................31 -

The Ethical Role and Responsibilities of a Lawyer-Ethicist Revisited: the Case of the Independent Counsel's Neutral Expert Consultant

Fordham Law Review Volume 68 Issue 4 Article 3 2000 The Ethical Role and Responsibilities of a Lawyer-Ethicist Revisited: The Case of the Independent Counsel's Neutral Expert Consultant Samuel Dash Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Samuel Dash, The Ethical Role and Responsibilities of a Lawyer-Ethicist Revisited: The Case of the Independent Counsel's Neutral Expert Consultant, 68 Fordham L. Rev. 1065 (2000). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol68/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Ethical Role and Responsibilities of a Lawyer-Ethicist Revisited: The Case of the Independent Counsel's Neutral Expert Consultant Cover Page Footnote Professor of Law, Georgetown University Law Center, Washington D.C.; B.S., Temple University; J.D., Harvard Law School; former Chief Counsel, U.S. Senate Watergate Committee; former member of ABA Standing Committee On Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility. This article is available in Fordham Law Review: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol68/iss4/3 RESPONSE THE ETHICAL ROLE AND RESPONSIBILITIES OF A LAWYER-ETMICIST REVISITED: THE CASE OF THE INDEPENDENT COUNSEL'S NEUTRAL EXPERT CONSULTANT Samuel Dash' N her recent Fordham Law Review article, Nancy Moore concluded that my role as contractual expert consultant to Independent Counsel Kenneth W. -

Independent Counsel, State Secrets, and Judicial Review

Nova Law Review Volume 18, Issue 3 1994 Article 8 Who Will Guard the Guardians? Independent Counsel, State Secrets, and Judicial Review Matthew N. Kaplan∗ ∗ Copyright c 1994 by the authors. Nova Law Review is produced by The Berkeley Electronic Press (bepress). https://nsuworks.nova.edu/nlr Kaplan: Who Will Guard the Guardians? Independent Counsel, State Secrets, Who Will Guard the Guardians? Independent Counsel, State Secrets, and Judicial Review Matthew N. Kaplan" TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................ 1788 II. BACKGROUND ........................... 1791 A. The Experience of the Iran-Contra Independent Counsel ................... 1791 1. A Hamstrung Independent Counsel ..... 1791 2. A Remaining Gap in the Government's System of Self-Policing ............. 1793 3. The Appearance of Executive Bias ..... 1794 a. The North Case ............... 1794 b. The Fernandez Case ............ 1799 B. Availability of Judicial Recourse? ......... 1801 1. The "No" Vote ................... 1802 2. The "Yes" Vote .................. 1805 a. A Historical Review ............ 1805 3. An Open Question ................. 1808 III. STATUTES ............................... 1809 A. Title VI of the Ethics in Government Act ..... 1809 B. The Classified Information ProceduresAct . .. 1812 IV. THE CONSTITUTION ........................ 1816 A. A Constitutionally Based Executive State Secrets Privilege? ..................... 1816 1. Executive Privilege-Origins ......... 1816 2. A Special Executive Privilege for State Secrets? . 1818 B. The Independent Counsel Context Is Special . 1820 * Law Clerk for the Honorable Walter K. Stapleton of the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit- J.D., New York University Law School, 1993; A.B., Princeton University, 1988. The author worked for Independent Counsel Lawrence Walsh from 1988 to 1989 as a paralegal. The views expressed in the article are the author's, and do not necessarily reflect the views of Independent Counsel Walsh or anyone else. -

An Original Model of the Independent Counsel Statute

Michigan Law Review Volume 97 Issue 3 1998 An Original Model of the Independent Counsel Statute Ken Gormley Duquesne University Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Legal History Commons, Legislation Commons, President/ Executive Department Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Ken Gormley, An Original Model of the Independent Counsel Statute, 97 MICH. L. REV. 601 (1998). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol97/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN ORIGINAL MODEL OF THE INDEPENDENT COUNSEL STATUTE Ken Gormley * TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 602 I. HISTORY OF THE INDEPENDENT COUNSEL STATUTE • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • . • • • • . • • • • • • 608 A. An Urgent Push fo r Legislation . .. .. .. .. 609 B. Th e Constitutional Quandaries . .. .. .. .. 613 1. Th e App ointments Clause . .. .. .. .. 613 2. Th e Removal Controversy .. ................ 614 3. Th e Separation of Powers Bugaboo . .. 615 C. A New Start: Permanent Sp ecial Prosecutors and Other Prop osals .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 617 D. Legislation Is Born: S. 555 .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 624 E. Th e Lessons of Legislative History . .. .. .. 626 II. THE FIRST TWENTY YEARS: ESTABLISHING THE LAW'S CONSTITUTIONALITY • . • • • • . • • • . • • • • . • • • • . • • • 633 III. REFORMING THE INDEPENDENT COUNSEL LAW • • . • 639 A. Refo rm the Method and Frequency of App ointing In dependent <;ounsels ..... :........ 641 1. Amend the Triggering Device . -

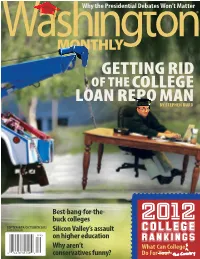

Getting Rid of Thecollege Loan Repo Man by STEPHEN Burd

Why the Presidential Debates Won’t Matter GETTING RID OF THECOLLEGE LOAN REPO MAN BY STEPHEN BURd Best-bang-for-the- buck colleges 2012 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2012 $5.95 U.S./$6.95 CAN Silicon Valley’s assault COLLEGE on higher education RANKINGS Why aren’t What Can College conservatives funny? Do For You? HBCUsHow do tend UNCF-member to outperform HBCUsexpectations stack in up successfully against other graduating students from disadvantaged backgrounds. higher education institutions in this ranking system? They do very well. In fact, some lead the pack. Serving Students and the Public Good: HBCUs and the Washington Monthly’s College Rankings UNCF “Historically black and single-gender colleges continue to rank Frederick D. Patterson Research Institute Institute for Capacity Building well by our measures, as they have in years past.” —Washington Monthly Serving Students and the Public Good: HBCUs and the Washington “When it comes to moving low-income, first-generation, minority Monthly’s College Rankings students to and through college, HBCUs excel.” • An analysis of HBCU performance —UNCF, Serving Students and the Public Good based on the College Rankings of Washington Monthly • A publication of the UNCF Frederick D. Patterson Research Institute To receive a free copy, e-mail UNCF-WashingtonMonthlyReport@ UNCF.org. MH WashMonthly Ad 8/3/11 4:38 AM Page 1 Define YOURSELF. MOREHOUSE COLLEGE • Named the No. 1 liberal arts college in the nation by Washington Monthly’s 2010 College Guide OFFICE OF ADMISSIONS • Named one of 45 Best Buy Schools for 2011 by 830 WESTVIEW DRIVE, S.W. The Fiske Guide to Colleges ATLANTA, GA 30314 • Named one of the nation’s most grueling colleges in 2010 (404) 681-2800 by The Huffington Post www.morehouse.edu • Named the No. -

Tending to Potted Plants: the Professional Identity Vacuum in Garcetti V

TENDING TO POTTED PLANTS: THE PROFESSIONAL IDENTITY VACUUM IN GARCETTI V. CEBALLOS Jeffrey W. Stempel* As people my age probably recall, Washington lawyer Brendan Sullivan1 briefly became a celebrity when defending former Reagan White House aide Oliver North before a Senate investigation. Senator Daniel K. Inouye (D-Haw.) was questioning Colonel North when Sullivan objected. “Let the witness object, if he wishes to,” responded Senator Inouye, to which Sullivan famously replied, “Well, sir, I’m not a potted plant. I’m here as the lawyer. That’s my job.”2 The episode was captured on live television and rebroadcast repeatedly, making Sullivan something of a hero to lawyers,3 even moderates and liberals * Doris S. & Theodore B. Lee Professor of Law, William S. Boyd School of Law, University of Nevada Las Vegas. Thanks to Bill Boyd, Doris Lee, Ted Lee, Ann McGinley, Jim Rogers, and John White. Special thanks to David McClure, Jeanne Price, Elizabeth Ellison, Chandler Pohl, and Kathleen Wilde for valuable research assistance. © 2011 Jeffrey W. Stempel 1 Sullivan was a partner in the Washington, D.C. firm Williams & Connolly, a firm with a sophisticated practice and prestigious reputation, particularly in the area of white-collar criminal defense. See Brendan V. Sullivan Jr., Partner, WILLIAMS & CONNOLLY LLP, http:// www.wc.com/bsullivan (last visited Mar. 9, 2012). Founding partner Edward Bennett Wil- liams is perhaps best known as a lawyer for his successful defense of Teamster’s Union head Jimmy Hoffa as well as defense of other public figures charged with crimes or corruption. See Firm Overview, WILLIAMS & CONNOLLY LLP, http://www.wc.com/about.html (last vis- ited Mar.