Imaging the Egyptian Obelisk at Kingston Lacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kingston Lacy Illustrated List of Pictures K Introduction the Restoration

Kingston Lacy Illustrated list of pictures Introduction ingston Lacy has the distinction of being the however, is a set of portraits by Lely, painted at K gentry collection with the earliest recorded still the apogee of his ability, that is without surviving surviving nucleus – something that few collections rival anywhere outside the Royal Collection. Chiefly of any kind in the United Kingdom can boast. When of members of his own family, but also including Ralph – later Sir Ralph – Bankes (?1631–1677) first relations (No.16; Charles Brune of Athelhampton jotted down in his commonplace book, between (1630/1–?1703)), friends (No.2, Edmund Stafford May 1656 and the end of 1658, a note of ‘Pictures in of Buckinghamshire), and beauties of equivocal my Chamber att Grayes Inne’, consisting of a mere reputation (No.4, Elizabeth Trentham, Viscountess 15 of them, he can have had little idea that they Cullen (1640–1713)), they induced Sir Joshua would swell to the roughly 200 paintings that are Reynolds to declare, when he visited Kingston Hall at Kingston Lacy today. in 1762, that: ‘I never had fully appreciated Sir Peter That they have done so is due, above all, to two Lely till I had seen these portraits’. later collectors, Henry Bankes II, MP (1757–1834), Although Sir Ralph evidently collected other – and his son William John Bankes, MP (1786–1855), but largely minor pictures – as did his successors, and to the piety of successive members of the it was not until Henry Bankes II (1757–1834), who Bankes family in preserving these collections made the Grand Tour in 1778–80, and paid a further virtually intact, and ultimately leaving them, in the visit to Rome in 1782, that the family produced astonishingly munificent bequest by (Henry John) another true collector. -

National Trust Report

England will lose all historical buildings und beautiful nature places... AUDIO (I've already sendet it to Ms Suter (N.T.2)) Kingston Lacy Library in Kingston Lacy Souvenirs from Egypt ...if the National Trust wouldn't exist. In the time of global warming it is very important that somebody looks after beautiful places, otherwise these places will be lost. But also objects which aren't in danger because of global warming are endangered if nobody looks after them. The National Trust saves historical houses und nature reserves and restores them when needed. This charity is really important for England. That is why you should learn more about this organisation. In my post you will find a lot of information about the National Trust and you will see what people who live in England think about the National Trust. The National Trust Introduction When you make a journey through England and you visit special places or buildings you might see a board with information about this place. On this board you will often see the company logo of the National Trust which is a branch of maple leaves on a green background. When I visited London, I saw many such information boards. The National Trust supports for example Carlyleꞌ s House, the Eastbury Manor House and other tourist attractions. At the beginning of my project I knew that the National Trust does exist. But I wanted to know more about this charity. I wanted to find out whether my hypothesis: “The National Trust is very important for the environment and the historical buildings of England” is true or not. -

Find out More *Dogs Not Permitted at These Events

Events for autumn/winter 2019 Dorset / Gloucestershire / Somerset / Wiltshire Corfe Castle Father Christmas at Christmas at Arlington Court Find out more The selection of events here is a small part of what’s on offer. You can visit the events page of the website at ©National Trust Images/John Bish Images/John Trust ©National ©National Trust Images/Hannah Burton nationaltrust.org.uk/ Events near you whats-on and use the search function to for autumn & find out everything that’s going on winter 2019 near you, or at your favourite place. Key to How to book symbols Facilities and access information can We have indicated where there is an event charge and where booking is necessary. Please note that normal admission charges apply Half-term be found on each unless you are a member. All children must be accompanied by an place’s homepage adult. And please check beforehand as to whether or not dogs are Halloween on the website, as welcome. We do take every effort to ensure that all event details are can contact details if correct at the time of going to press. The National Trust reserves the Christmas right to cancel or change events if necessary. you require further Tickets are non-refundable. Father information. Christmas ©National Trust Images/John Millar New Year’s ramble Walk with an archaeologist BATH AND NORTH Sun 5 Jan, 9.30am-2pm BRISTOL Sat 16 Nov, 2-4pm On this fairly fast-paced guided walk of the Discover the secrets of Cadbury Camp Iron EAST SOMERSET Bath Skyline you may burn off some Age hill fort on this walk with archaeologist Christmas calories, but a diversion to Prior Leigh Woods Martin Papworth. -

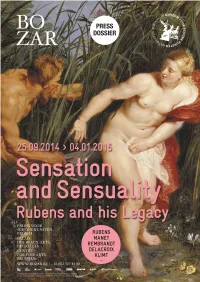

'Rubens and His Legacy' Exhibition in Focus Guide

Exhibition in Focus This guide is given out free to teachers and full-time students with an exhibition ticket and ID at the Learning Desk and is available to other visitors from the RA Shop at a cost of £5.50 (while stocks last). ‘Rubens I mention in this place, as I think him a remarkable instance of the same An Introduction to the Exhibition mind being seen in all the various parts of the art. […] [T]he facility with which he invented, the richness of his composition, the luxuriant harmony and brilliancy for Teachers and Students of his colouring, so dazzle the eye, that whilst his works continue before us we cannot help thinking that all his deficiencies are fully supplied.’ Sir Joshua Reynolds, Discourse V, 10 December 1772 Introduction Written by Francesca Herrick During his lifetime, the Flemish master Sir Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) For the Learning Department was the most celebrated artist in Europe and could count the English, French © Royal Academy of Arts and Spanish monarchies among his prestigious patrons. Hailed as ‘the prince of painters and painter of princes’, he was also a skilled diplomat, a highly knowledgeable art collector and a canny businessman. Few artists have managed to make such a powerful impact on both their contemporaries and on successive generations, and this exhibition seeks to demonstrate that his Rubens and His Legacy: Van Dyck to Cézanne continued influence has had much to do with the richness of his repertoire. Its Main Galleries themes of poetry, elegance, power, compassion, violence and lust highlight the 24 January – 10 April 2015 diversity of Rubens’s remarkable range and also reflect the main topics that have fired the imagination of his successors over the past four centuries. -

![The Rosetta Stone, British Museum, London Hieroglyphic, [From the Greek=Priestly Carving], Type of Writing Used in Ancient Egypt](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5650/the-rosetta-stone-british-museum-london-hieroglyphic-from-the-greek-priestly-carving-type-of-writing-used-in-ancient-egypt-755650.webp)

The Rosetta Stone, British Museum, London Hieroglyphic, [From the Greek=Priestly Carving], Type of Writing Used in Ancient Egypt

T h e R o s e t t a S t o n e Languages: Egyptian and Greek, Using three scripts -- Hieroglyphic, Demotic Egyptian, and Greek. Found 1799 by the French in Egypt Originally from 196 B.C. The Rosetta Stone, British Museum, London Hieroglyphic, [from the Greek=priestly carving], type of writing used in ancient Egypt. Similar pictographic styles of Crete, Asia Minor, and Central America and Mexico are also called hieroglyphics. Interpretation of Egyptian hieroglyphics, begun by Thomas Young and J. F. Champollion and others, is virtually complete. The meanings of hieroglyphics often seem arbitrary and are seldom obvious. Egyptian hieroglyphics were already perfected in the first dynasty (3110-2884 B.C.), but they began to go out of use in the Middle Kingdom and after 500 B.C. were virtually unused. There were basically 604 symbols that might be put to three types of uses (although few were used for all three purposes). 1) They could be used as ideograms, as when a sign resembling a snake meant "snake." [See chart above.] 2) They could be used as a phonogram (or a phonetic letter similar to our alphabet), as when the pictogram of an owl represented the sign or letter “m,” because the word for owl had “m” as its principal consonant sound. [It would be like us using a picture of a snake for the letter “s.”] 3) They could be used as a determinative, an unpronounced symbol placed after an ambiguous sign to indicate its classification (e.g., an eye to indicate that the preceding word has to do with looking or seeing). -

Webfile121848.Pdf

0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Press release ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Catalogue text: Nico Van Hout - Curator ...................................................................................................... 6 Gallery texts ................................................................................................................................................... 11 Transversal Activities ................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR MUSIC ......................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR LITERATURE ............................................................................................................................. 17 BOZAR EXPO ........................................................................................................................................... 17 BOZAR CINEMA ...................................................................................................................................... 18 Rubens for families ...................................................................................................................................... 19 Disovery trails for families (6>12) ........................................................................................................... 19 -

News Release

NEWS RELEASE FOURTH STREET AT CONSTITUTION AVENUE NW WASHINGTON DC 20565 . 737-4215/842-6353 EXHBITION FACT SHEET Title; THE TREASURE HOUSES OF BRITAIN: FIVE HUNDRED YEARS OF PRIVATE PATRONAGE AND ART COLLECTING Patrons: Their Royal Highnesses The Prince and Princess of Wales Dates; November 3, 1985 through March 16, 1986, exactly one week later than previously announced. (This exhibition will not travel. Loans from houses open to view are expected to remain in place until the late summer of 1985 and to be returned before many of the houses open for their visitors in the spring of 1986.) Credits; This exhibition is made possible by a generous grant from the Ford Motor Company. The exhibition was organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, in collaboration v\n.th the British Council and is supported by indemnities from Her Majesty's Treasury and the U.S. Federal Council on the Arts and Humanities. Further British assistance was supplied by the National Trust and the Historic Houses Association. History of the exhibition; The suggestion that the National Gallery of Art consider holding a major exhibition devoted to British art was made by the British Council in 1979. J. Carter Brown, Director of the National Gallery, responded with the idea of an exhibition on the British Country House as a "vessel of civilization," bringing together works of art illustrating the extraordinary achievement of collecting and patronage throughout Britain over the past five hundred years. As this concept carried with it the additional, contemporary advantage of stimulating greater interest in and support of those houses open to public viewing, it was enthusiastically endorsed by the late Lord Howard of Henderskelfe, then-Chairman of the Historic Houses Association, Julian Andrews, Director of the Fine Arts Department of the British Council, and Lord Gibson, Chairman of the National Trust. -

Sir Roger Pratt's Library

Reading as a Gentleman and an Architect: Sir Roger Pratt’s Library by KIMBERLEY SKELTON This article illuminates the changes in English seventeenth-century architectural practice when members of the gentry educated themselves as architectural professionals and as a result several became noted practitioners. The author analyses the rarely examined notes and library of Sir Roger Pratt to explore how a seventeenth-century gentleman both studied and practised architecture literally as both gentleman and architect. Also she considers Pratt’s notes chronologically, rather than according to their previous thematic reorganisation by R. T. Gunther (1928), and offers a full reconstruction of Pratt’s library beyond Gunther’s catalogue of surviving volumes. Mid-seventeenth-century England experienced a sharp change in architectural practice and education. For the first time, members of the gentry began to design buildings and to educate themselves as professionals in architecture. From the late 1650s, Sir Roger Pratt designed country houses, and several members of the landed and educated classes became prominent architects: Sir Christopher Wren, Robert Hooke, Hugh May, William Winde, William Samwell, and William Talman. These gentleman architects brought new techniques to the study of architecture since they were more highly trained in analysing text than image. Scholars have yet to consider the seventeenth-century emergence of the gentleman architect in detail; they have focused more on monographic studies of architects, patronage, and building types than on shifts in the architectural profession.1 This article explores how a seventeenth-century gentleman would both study and practise architecture; it considers the rarely examined library and manuscript notes of Sir Roger Pratt.2 I argue that Pratt practised and read as literally patron and architect – using the techniques of a patron to answer the questions of an architect designing for English geographical and social particularities. -

'X'marks the Spot: the History and Historiography of Coleshill House

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Department of History ‘X’ Marks the Spot: The History and Historiography of Coleshill House, Berkshire by Karen Fielder Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2012 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY Doctor of Philosophy ‘X’ MARKS THE SPOT: THE HISTORY AND HISTORIOGRAPHY OF COLESHILL HOUSE, BERKSHIRE by Karen Fielder Coleshill House was a much admired seventeenth-century country house which the architectural historian John Summerson referred to as ‘a statement of the utmost value to British architecture’. Following a disastrous fire in September 1952 the remains of the house were demolished amidst much controversy shortly before the Coleshill estate including the house were due to pass to the National Trust. The editor of The Connoisseur, L.G.G. Ramsey, published a piece in the magazine in 1953 lamenting the loss of what he described as ‘the most important and significant single house in England’. ‘Now’, he wrote, ‘only X marks the spot where Coleshill once stood’. Visiting the site of the house today on the Trust’s Coleshill estate there remains a palpable sense of the absent building. This thesis engages with the house that continues to exist in the realm of the imagination, and asks how Coleshill is brought to mind not simply through the visual signals that remain on the estate, but also through the mental reckoning resulting from what we know and understand of the house. In particular, this project explores the complexities of how the idea of Coleshill as a canonical work in British architectural histories was created and sustained over time. -

Dorset Gardens Tour

Dorset Gardens Tour Destinations: Dorset Coast & England Trip code: LHGDT HOLIDAY OVERVIEW Dorset has a wonderful collection of stately homes surrounded by long-established gardens. Dorset’s southerly location allows subtropical plants to thrive at Abbotsbury – a garden noted for its Camellia groves and magnolias. The design of Minterne House gardens was inspired by Capability Brown while the Victorian gardens as Larmer Tree were laid out by General Pitt Rivers. From the gardens of 15th century Athelhampton House to the large formal gardens of Kingston Lacy, there’s something for everyone. WHAT'S INCLUDED • High-quality Full Board en-suite accommodation and excellent food in our Country House • The guidance and services of our knowledgeable HF Holidays’ leader, ensuring you get the most from your holiday • All transport to and from gardens on a comfortable, good-quality coach • All admission costs including those for English Heritage, National Trust, and RHS Gardens. Some venues have stately homes/houses which incur a separate admission fee should you wish to visit - you will need to pay for this yourself. www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Attractive formal gardens and extensive parkland at Kingston Lacy • Magnificent garden at Athelhampton surrounding the 15th century house • Compton Acres – the south’s finest historical gardens • The subtropical gardens at Abbotsbury are famous in Dorset of their Rhodeodendrons, Hydrangea collections and a charming Victorian garden. ITINERARY Day 1: Arrival Day Check-in starts from 2.30pm (Best and Better rooms from 1pm). All guests are invited to join us for afternoon tea where we’ll introduce your leader. -

Conservation Management Plans Relating to Historic Designed Landscapes, September 2016

Conservation Management Plans relating to Historic Designed Landscapes, September 2016 Site name Site location County Country Historic Author Date Title Status Commissioned by Purpose Reference England Register Grade Abberley Hall Worcestershire England II Askew Nelson 2013, May Abberley Hall Parkland Plan Final Higher Level Stewardship (Awaiting details) Abbey Gardens and Bury St Edmunds Suffolk England II St Edmundsbury 2009, Abbey Gardens St Edmundsbury BC Ongoing maintenance Available on the St Edmundsbury Borough Council Precincts Borough Council December Management Plan website: http://www.stedmundsbury.gov.uk/leisure- and-tourism/parks/abbey-gardens/ Abbey Park, Leicester Leicester Leicestershire England II Historic Land 1996 Abbey Park Landscape Leicester CC (Awaiting details) Management Management Plan Abbotsbury Dorset England I Poore, Andy 1996 Abbotsbury Heritage Inheritance tax exempt estate management plan Natural England, Management Plan [email protected] (SWS HMRC - Shared Workspace Restricted Access (scan/pdf) Abbotsford Estate, Melrose Fife Scotland On Peter McGowan 2010 Scottish Borders Council Available as pdf from Peter McGowan Associates Melrose Inventor Associates y of Gardens and Designed Scott’s Paths – Sir Walter Landscap Scott’s Abbotsford Estate, es in strategy for assess and Scotland interpretation Aberdare Park Rhondda Cynon Taff Wales (Awaiting details) 1997 Restoration Plan (Awaiting Rhondda Cynon Taff CBorough Council (Awaiting details) details) Aberdare Park Rhondda Cynon Taff -

History of Parliament Online

THE HISTORY OF PARLIAMENT TRUST Review of activities in the year 2011-12 July 2012 - 1 - Objectives and Activities of the History of Parliament Trust The History of Parliament is a major academic project to create a scholarly reference work describing the members, constituencies and activities of the Parliament of England and the United Kingdom. The volumes either published or in preparation cover the House of Commons from 1386 to 1868 and the House of Lords from 1660 to 1832. They are widely regarded as an unparalleled source for British political, social and local history. The volumes consist of detailed studies of elections and electoral politics in each constituency, and of closely researched accounts of the lives of everyone who was elected to Parliament in the period, together with surveys drawing out the themes and discoveries of the research and adding information on the operation of Parliament as an institution. The History has published 21,420 biographies and 2,831 constituency surveys in ten sets of volumes (41 volumes in all). They deal with 1386-1421, 1509-1558, 1558-1603, 1604-29, 1660-1690, 1690-1715, 1715-1754, 1754-1790, 1790-1820 and 1820-32. All of these volumes save those most recently published (1604-29) are now available on www.historyofparliamentonline.org . The History’s staff of professional historians is currently researching the House of Commons in the periods 1422-1504, 1640-1660, and 1832-1868, and the House of Lords in the periods 1603-60 and 1660-1832. The three Commons projects currently in progress will contain a further 7,251 biographies of members of the House of Commons and 861 constituency surveys.