VFW #109!” What an Optimist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Note to Users

NOTE TO USERS Page(s) not included in the original manuscript are unavailable from the author or university. The manuscript was microfilmed as received 88-91 This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" X 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. AccessinglUMI the World’s Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Mi 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8820263 Leigh Brackett: American science fiction writer—her life and work Carr, John Leonard, Ph.D. -

To Sunday 31St August 2003

The World Science Fiction Society Minutes of the Business Meeting at Torcon 3 th Friday 29 to Sunday 31st August 2003 Introduction………………………………………………………………….… 3 Preliminary Business Meeting, Friday……………………………………… 4 Main Business Meeting, Saturday…………………………………………… 11 Main Business Meeting, Sunday……………………………………………… 16 Preliminary Business Meeting Agenda, Friday………………………………. 21 Report of the WSFS Nitpicking and Flyspecking Committee 27 FOLLE Report 33 LA con III Financial Report 48 LoneStarCon II Financial Report 50 BucConeer Financial Report 51 Chicon 2000 Financial Report 52 The Millennium Philcon Financial Report 53 ConJosé Financial Report 54 Torcon 3 Financial Report 59 Noreascon 4 Financial Report 62 Interaction Financial Report 63 WSFS Business Meeting Procedures 65 Main Business Meeting Agenda, Saturday…………………………………...... 69 Report of the Mark Protection Committee 73 ConAdian Financial Report 77 Aussiecon Three Financial Report 78 Main Business Meeting Agenda, Sunday………………………….................... 79 Time Travel Worldcon Report………………………………………………… 81 Response to the Time Travel Worldcon Report, from the 1939 World Science Fiction Convention…………………………… 82 WSFS Constitution, with amendments ratified at Torcon 3……...……………. 83 Standing Rules ……………………………………………………………….. 96 Proposed Agenda for Noreascon 4, including Business Passed On from Torcon 3…….……………………………………… 100 Site Selection Report………………………………………………………… 106 Attendance List ………………………………………………………………. 109 Resolutions and Rulings of Continuing Effect………………………………… 111 Mark Protection Committee Members………………………………………… 121 Introduction All three meetings were held in the Ontario Room of the Fairmont Royal York Hotel. The head table officers were: Chair: Kevin Standlee Deputy Chair / P.O: Donald Eastlake III Secretary: Pat McMurray Timekeeper: Clint Budd Tech Support: William J Keaton, Glenn Glazer [Secretary: The debates in these minutes are not word for word accurate, but every attempt has been made to represent the sense of the arguments made. -

VOID 23 Written, Illustrated, and Executed by Bhob Stewart, an Unsung Genius

^ONTHLlC^ LW gOltfHN INSTANT NO%Ai.&'A is edited by TED WHITE (107 Christopher St., New York 14, NY), GREG- BENFORD (204 Foreman Ave., Norman, Okla.), and FETE GRAHAM (still c/0 White); and is published by the aged and failing QWERTYUIOPress Gestetner 160. As usual, VOIR is available for money (25/ or 1/-), trade (all for all) contribution, or regular letters of comment. British agent is RON BENNETT (7 Southway, Arthurs Ave., Harrogate, Yorks., England). We're dickering for a German agent. Deadline THE UUIEUSH for material for next issue: February 15th. INTRODUCTION TO VOID 23 written, illustrated, and executed by Bhob Stewart, an unsung genius . i COVER by Lee Hoffmeta, and taken by her from her cover for QUANDRY 27/28 ............. 1 GAMBIT 40, the only column which is also a fanzine, by Ted White ......................................................................... 2 HAPPY BENFORD CHATTER by Greg Benford ..................................................................................................................................... 6 AN-OPENED LETTER TO WALT WILLIS by Larry & Noreen Shaw ................................................................................................. 7 BELFASTERS: WALT WILLIS, NEO-GENIUS by John perry, and reprinted from GRUE 23 ......................................... 8 WAN: SOME SMALL & RAMBLING REMINISCENCES by Lee Hoffman ............................................................................................ 13 WHERE THERE'S A WILLIS, THERE'S A WAYSGOOSE by Bob Shaw, and "Waysgoose" -

13Th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture

13th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture James F. O’Gorman Non-fiction 38.65 ACROSS THE SEA OF GREGORY BENFORD SF 9.95 SUNS Affluent Society John Kenneth Galbraith 13.99 African Exodus: The Origins Christopher Stringer and Non-fiction 6.49 of Modern Humanity Robin McKie AGAINST INFINITY GREGORY BENFORD SF 25.00 Age of Anxiety: A Baroque W. H. Auden Eclogue Alabanza: New and Selected Martin Espada Poetry 24.95 Poems, 1982-2002 Alexandria Quartet Lawrence Durell ALIEN LIGHT NANCY KRESS SF Alva & Irva: The Twins Who Edward Carey Fiction Saved a City And Quiet Flows the Don Mikhail Sholokhov Fiction AND ETERNITY PIERS ANTHONY SF ANDROMEDA STRAIN MICHAEL CRICHTON SF Annotated Mona Lisa: A Carol Strickland and Non-fiction Crash Course in Art History John Boswell From Prehistoric to Post- Modern ANTHONOLOGY PIERS ANTHONY SF Appointment in Samarra John O’Hara ARSLAN M. J. ENGH SF Art of Living: The Classic Epictetus and Sharon Lebell Non-fiction Manual on Virtue, Happiness, and Effectiveness Art Attack: A Short Cultural Marc Aronson Non-fiction History of the Avant-Garde AT WINTER’S END ROBERT SILVERBERG SF Austerlitz W.G. Sebald Auto biography of Miss Jane Ernest Gaines Fiction Pittman Backlash: The Undeclared Susan Faludi Non-fiction War Against American Women Bad Publicity Jeffrey Frank Bad Land Jonathan Raban Badenheim 1939 Aharon Appelfeld Fiction Ball Four: My Life and Hard Jim Bouton Time Throwing the Knuckleball in the Big Leagues Barefoot to Balanchine: How Mary Kerner Non-fiction to Watch Dance Battle with the Slum Jacob Riis Bear William Faulkner Fiction Beauty Robin McKinley Fiction BEGGARS IN SPAIN NANCY KRESS SF BEHOLD THE MAN MICHAEL MOORCOCK SF Being Dead Jim Crace Bend in the River V. -

S67-00097-N210-1994-03 04.Pdf

SFRA Reriew'210, MarchI April 1994 BFRAREVIEW laauB #210. march/Aprll1BB~ II THIIIIIUE: IFlllmlnll IFFIIII: President's Message (Mead) SFRA Executive Committee Meeting Minutes (Gordon) New Members & Changes of Address "And Those Who Can't Teach.. ." (Zehner) Editorial (Mallett) IEnEIll mIICEWn!l: Forthcoming Books (BarronlMallett) News & Information (BarronlMallett) FEITUREI: Feature Article: "Animation-Reference. History. Biography" (Klossner) Feature Review: Zaki. Hoda M. Phoenix Renewed: The Survival and Mutation of Utopian ThouFdlt in North American Science Fiction, 1965- 1982. Revised Edition. (Williams) An Interview with A E. van Vogt (Mallett/Slusser) REVIEWS: Fledll: Acres. Mark. Dragonspawn. (Mallett) Card. Orson Scott. Future on Fire. (Collings) Card. Orson Scott. Xenoclde. (Brizzi) Cassutt. Michael. Dragon Season. (Herrin) Chalker. Jack L. The Run to Chaos Keep. (Runk) Chappell. Fred. More Shapes Than One. (Marx) Clarke. Arthur C. & Gentry Lee. The Garden ofRama. (Runk) Cohen. Daniel. Railway Ghosts and Highway Horrors. (Sherman) Cole. Damaris. Token ofDraqonsblood. (Becker) Constantine. Storm. Aleph. (Morgan) Constantine. Storm. Hermetech. (Morf¥in) Cooper. Louise. The Pretender. (Gardmer-Scott) Cooper. Louise. Troika. (Gardiner-Scott) Cooper. Louise. Troika. (Morgan) Dahl. Roald. The Minpins. (Spivack) Danvers. Dennis. Wilderness. (Anon.) De Haven. Tom. The End-of-Everything Man. (Anon.) Deitz. Tom. Soulsmith. (posner) Deitz. Tom. Stoneskin's Revenge. (Levy) SFRA Review 1210, MarchI Apm 1994 Denning. Troy. The Verdant Passage. (Dudley) Denton. Bradley. Buddy HoDy ~ Ahire and WeD on Ganymede. (Carper) Disch. Tom. Dark Ver.s-es & Light. (Lindow) Drake. David. The Jungle. (Stevens) Duane. Diane & Peter Morwood. Space Cops Mindblast. (Gardiner-Scon) Emshwiller. Carol. The Start ofthe End oflt AU. (Bogstad) Emshwiller. Carol. The Start ofthe End oflt AU. -

April 2018 NASFA Shuttle

Te Shutle April 2018 The Next NASFA Meeting is 6P Saturday 21 April 2018 at the New Church Location All other months are definitely open.) d Oyez, Oyez d FUTURE CLUB MEETING DATES/LOCATIONS At present, all 2018 NASFA Meetings are expected to be at The next NASFA Meeting will be 21 April 2018, at the reg- the normal meeting location except for October (due to Not-A- ular meeting location and the NEW regular time (6P). The Con 2018). Most 2018 meetings are on the normal 3rd Saturday. Madison campus of Willowbrook Baptist Church is at 446 Jeff The only remaining meeting currently not scheduled for the Road—about a mile from the previous location. See the map normal weekend is: below for directions to the church. See the map on page 2 for a •11 August—a week earlier (2nd Saturday) to avoid Worldcon closeup of parking at the church as well as how to find the CHANGING SHUTTLE DEADLINES meeting room (“The Huddle”), which is close to one of the In general, the monthly Shuttle production schedule has been back doors toward the north side of the church. Please do not moved to the left a bit (versus prior practice). Though things try to come in the (locked) front door. are a bit squishy, the current intent is to put each issue to bed APRIL PROGRAM about 6–8 days before each month’s meeting. Les Johnson will speak on “Graphene—The Superstrong, Please check the deadline below the Table of Contents each Superthin, and Superversatile Material That Will Revolutionize month to submit news, reviews, LoCs, or other material. -

Fancyclopedia: F – Version 1 (May 2009)

The Canadian Fancyclopedia: F – Version 1 (May 2009) An Incompleat Guide To Twentieth Century Canadian Science Fiction Fandom by Richard Graeme Cameron, BCSFA/WCSFA Archivist. A publication of the British Columbia Science Fiction Association (BCSFA) And the West Coast Science Fiction Association (WCSFA). You can contact me at: [email protected] Canadian fanzines are shown in red, Canadian Apazines in Green, Canadian items in purple, Foreign items in blue. F FACES / FAERIE / FALCON / FALCON SF&F SOCIETY / FANACTIC / FANADIAN / FANATICUS / FANCESTOR WORSHIP / FANCYCLOPEDIA / FANDOM / FANDOMS (Numbered Eras) / FANDOMS CANADIAN (Numbered Eras) / THE FANDOM ZONE / FAN DRINKS / FANED - FAN ED / FANERGY / FAN FEUD / FAN FILMS / FAN FILMS ( AMERICAN ) / FAN FILMS ( BRITISH ) / FAN FILMS ( CANADIAN ) / FANICHE / FANNISH DRINKSH BOOK / FANNISH LEGENDS / FANTARAMA / FAN-TASMS / FANTASTELLAR ASSOCIATION / FANTASTOLOGY / FANTASY / FANTASY CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM / FANTASY PICTORIAL / FANTHOLOGY 76 / FANTIQUARIAN / THE FANTIQUARIAN CHRONICLER / FANUCK - FANUCKER / FAST- FORWARD / FAT, OLD, AND BORING / FAZZ BAZZ / FELTIPIXINE / FEM FAN - FEMME FAN / FEN / FENAISSANCE / FEN AND THE ART OF FANZINE PUBLISHING / FEN COMMANDMENTS / FERGONOMICS / FERSHIMMELT / FEWMETS / FIAGGH / FIAWOL / FICTONS FREE-FOR-ALL / FIE / FIJAGH / FILK / FILKSONG / FILKER / FILK ROOM / FILKZINE / FILLER / FILLERS / FINAL FRONTIER / THE FINAL FRONTIER / FIRST CANADIAN CARBONZINE / FIRST CANADIAN FAN CLUB / FIRST CANADIAN FAN DIRECTORY / FIRST CANADIAN FAN ED / FIRST CANADIAN -

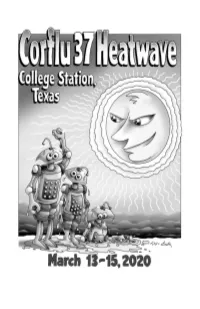

Corflu 37 Program Book (March 2020)

“We’re Having a Heatwave”+ Lyrics adapted from the original by John Purcell* We’re having a heatwave, A trufannish heatwave! The faneds are pubbing, The mimeo’s humming – It’s Corflu Heatwave! We’re starting a heatwave, Not going to Con-Cave; From Croydon to Vegas To bloody hell Texas, It’s Corflu Heatwave! —— + scansion approximate (*with apologies to Irving Berlin) 2 Table of Contents Welcome to Corflu 37! The annual Science Fiction Fanzine Fans’ Convention. The local Texas weather forecast…………………………………….4 Program…………………………………………………………………………..5 Local Restaurant Map & Guide…………..……………………………8 Tributes to Steve Stiles:…………………………………………………..12 Ted White, Richard Lynch, Michael Dobson Auction Catalog……………………………………………………………...21 The Membership…………………………………………………………….38 The Responsible Parties………………………………………………....40 Writer, Editor, Publisher, and producer of what you are holding: John Purcell 3744 Marielene Circle, College Station, TX 77845 USA Cover & interior art by Teddy Harvia and Brad Foster except Steve Stiles: Contents © 2020 by John A. Purcell. All rights revert to contrib- uting writers and artists upon publication. 3 Your Local Texas Weather Forecast In short, it’s usually unpredictable, but usually by mid- March the Brazos Valley region of Texas averages in dai- ly highs of 70˚ F, and nightly lows between 45˚to 55˚F. With that in mind, here is what is forecast for the week that envelopes Corflu Heatwave: Wednesday, March 11th - 78˚/60˚ F or 26˚/16˚C Thursday, March 12th - 75˚/ 61˚ F or 24˚/15˚ C Friday, March 13th - 77˚/ 58˚ F or 25 / 15˚ C - Saturday, March 14th - 76˚/ 58 ˚F or 24 / 15˚C Sunday, March 15th - 78˚ / 60˚ F or 26˚/16˚C Monday March 16th - 78˚ / 60˚ F or 26˚/ 16˚C Tuesday, March 17th - 78˚ / 60˚ F or 26˚/ 16˚C At present, no rain is in the forecast for that week. -

Comics and Science Fiction Fandom Collection MS-0506

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8tx3jhr No online items Comics and Science Fiction Fandom Collection MS-0506 Anna Culbertson Special Collections & University Archives 11/25/2014 5500 Campanile Dr. MC 8050 San Diego, CA 92182-8050 [email protected] URL: http://library.sdsu.edu/scua Comics and Science Fiction MS-0506 1 Fandom Collection MS-0506 Contributing Institution: Special Collections & University Archives Title: Comics and Science Fiction Fandom Collection Identifier/Call Number: MS-0506 Physical Description: 19.25 Linear Feet Date (inclusive): 1934- Language of Material: English . Scope and Contents The Comics and Science Fiction Fandom Collection consists of publications, ephemera, memorabilia and artwork acquired from 2004- at various comics and science fiction conventions and conferences in the Southern California region, particularly San Diego Comic-Con International. Promotional literature for related degree programs and centers around the country, as well as programs for academic conferences, document a rise in popular arts studies over the past decade, while a substantial collection of promotional ephemera and memorabilia demonstrate the broad range and evolution of fandom that remains a hallmark of Southern California. A significant concentration of rare and early fanzines dating back to the 1930s reflects the evolution and involvement of the science fiction fandom community over the years. Additions are current and ongoing. Arrangement Note I. San Diego Comic-Con, International 1. Official publications 2. Convention-related publications II. Other conferences and conventions III. Education and scholarship 1. Promotional literature 2. Essays and articles IV. Professional organizations V. Fandom periodicals 1. Fanzines 2. Specialty publications VI. Ephemera VII. Artwork and photographs VIII. -

Cience-∫Iction ∫Ive-®Early Issue Number Ten November 1996

>cience-∫iction ∫ive-®early Issue Number Ten November 1996 . Lee Hoffman Founder, editor emeritus . Guest editor-publishers: Andy Hooper, Jeff Schalles, & Geri Sullivan . Front & back cover . Ray Nelson. Covers Looking Forward to the Past (editorial) . Lee Hoffman . 2 The Last Mimeo on Earth (editorial) . Jeff Schalles. 4 Progress is Where You Find It . F.M. Busby . 5 The Purple Fields of Fanac, Part IV. Ted White . 7 A Model Fan, or Your Ass is on the Net . Vijay Bowen . 10 A Great Place to Live . Lee Hoffman . 15 The Faces of Science-Fiction Five-Yearly . Jeff Schalles & Geri Sullivan . 18 Two Moons . Victor M. Gonzalez . 25 Mathemaku No. 6a . Bob Grumman . 30 Oldies But Goodies (reprint) . Robert Bloch. 31 The Last Corflu . Dan Steffan . 35 Walking into Midnight (editorial) . Andy Hooper . 37 !Nissassa, Part 10 . Nalrah Nosille. 42 Art Credits: The Heroic Ken Fletcher -- 42, 44 Gary Ross Hoffman -- 17, 31, 33, 41 Lee Hoffman -- 2, 3, 15, 16 William Rotsler --1, 3, 4, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 Stu Shiffman -- 31, 32, 34 Craig Smith -- 25 Steve Stiles -- 7, 8, 15 Shelby Vick -- 4, 5, 9 Reed Waller -- 10, 11, 13, 14 Winnie Winston -- 1 (NLCRA Blue Eagle) Interlinos: Dave Messer, 1; MUSRUM by Eric Thacker & Anthony Earnshaw (1968), contributed by Dave Langford, 7, 8, 9; Lee Hoffman, SF5Y#5, 38 SCIENCE-FICTION FIVE-YEARLY, the lustrous, archaically lustful fanzine published once every lustrum. Holding this issue in your hands, reading its contents, and sending a letter of comment to ye faithful editors is the lustral equivalent of climbing the Tower of Trufandom and cranking the Enchanted Duplicator for 3,209 rotations. -

Fanzine Joan Bowers Helen J

Richard Delap Stuart Shiffman Camestros Felapton Natalie Luhrs Sheryl Birkhead Bob Devney Arthur D. Hlavaty Phil Foglio Galen Dara Shamus Young Jim C. Hines Sarah Gailey Ariela Housman George Barr Jacqueline Lichtenberg Foz Meadows Frank Wu Tom Digby Harry Warner Jr. Brad W. Foster Mia Sereno Grace P. Fong Alexei Panshin Elizabeth Fishman Doug Lovenstein Joan Hanke-Woods Morgan Holmes Ruth Berman Ninni Aalto John Scalzi Mark Oshiro Sharon N. Farber Grant Canfield Christian Quinot Elsa Sjunneson-Henry Bogi Takács Sandra Miesel Elizabeth Leggett Jack Gaughan Kameron Hurley Ted Pauls Cedar Sanderson Teddy Harvia Randall Munroe Jim Barker Dave Freer Amanda S. Green Evelyn C. Leeper William Rotsler Taral Wayne Ian Gunn Maureen Kincaid Speller Liz Bourke Arthur "ATom" Thomson Laura Basta Ted White Vesa Lehtimäki Adam Whitehead Freddie Baer Mandie Manzano Elise Matthesen Jeff Berkwits Joseph T. Major Frederik Pohl Stephen Fabian Iain Clark Joe Mayhew Piers Anthony John L. Flynn John Hertz Diana Gallagher Wu D. West Victoria Poyser Sarah Webb Cora Buhlert Sara Felix Banks Mebane Wilson Tucker Linda Michaels Abigail Nussbaum Maurine Starkey Fan Artist Dan Steffan Vaughn Bodé Laura J. Mixon Maya Hahto Harlan Ellison Fan Writer Roy Kettle Merle Insinga Kukuruyo Owen Whiteoak Bob Vardeman Alan F. Beck Alexis A. Gilliland Chuck Tingle Sherlock Alasdair Stuart Wendy Fletcher James Nicoll Harry Bell Bob Shaw Alicia Austin Paul J. Willis Cheryl Morgan Dave Howell disse86 Meg Frank Simon Ounsley Walt Willis Diana Harlan Stein Rosemary Ullyot James Bacon Charles Payseur Steven Fox Mike Gilbert Don C. Thompson Camille Cazedessus Jr. Spring Schoenhuth Norm Clarke Andrew Hooper Jeff Jones Leigh Edmonds Cliff Gould Suzanne Tompkins Peggy Ranson Frank Lunney Johnny Chambers Avedon Carol David Langford Steven Diamond Sue Mason Susan Wood Glicksohn Anne C. -

Asfacts April18.Pub

set in 1883 New Mexico, was published under the pen name Keith Jarrod in 1979. He also wrote several action/adventure and near- future works under pseudonyms: James Axler for several Deathlands and Outlanders books, Richard Austin for The Guardians series, Robert Baron for the Stormrider trilogy, S. L. Hunter for two Donovan Steele books, and by Craig W. Chrissinger Alex Archer for many books in the Rogue Angel series. Victor Milàn, New Mexico science fiction/fantasy All in all, he had almost 100 novels and numerous short author, died late afternoon February 13 in Albuquerque. stories published. He was 63 years old. Milan died at 4:30 pm at Lovelace Recent research also has found that Milan wrote the Westside Hospital as a result of complications of pneu- No-Frills Western, published in 1981 from Jove. The monia, brought on by multiple myeloma cancer. plain cover promises, “Complete with everything: Cow- Born August 3, 1954, in Tulsa, OK, Victor Wood- boys, horses, lady, blood, dust, guns.” ward Milan was known for his libertarian-oriented sci- Milan also was a member of the Critical Mass writ- ence fiction and an interest in cybernetics. In 1986, he ers group, a peer-to-peer group of NM writers that he received the Prometheus Award for early novel, The Cy- once asserted is a "massive help in critiquing and helping bernetic Samurai. Most recently, he produced three nov- each other grow as writers." And in 1979 he was editor of els in the Dinosaur Lords series, with The Dinosaur Prin- the bulletin of the Science Fiction Writers of America.