MA Rural Development Project , 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DRAFT IDP Attached

BUFFALO CITY METROPOLITAN MUNICIPALITY 2019/20 DRAFT INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN REVIEW “A City Hard at Work” Third (3rd) Review of the 2016-2021 Integrated Development Plan as prescribed by Section 34 of the Local Government Municipal Systems Act (2000), Act 32 of 2000 Buffalocity Metropolitan Municipality | Draft IDP Revision 2019/2020 _________________________________________________________________________________ Table of Content GLOSSARY OF ABBREVIATIONS 3 MAYOR’S FOREWORD 5 OVERVIEW BY THE CITY MANAGER 7 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 9 SECTION A INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 15 SECTION B SITUATION ANALYSIS PER MGDS PILLAR 35 SECTION C SPATIAL DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK 217 SECTION D OBJECTIVES, STRATEGIES, INDICATORS, 240 TARGETS AND PROJECTS SECTION E BUDGET, PROGRAMMES AND PROJECTS 269 SECTION F FINANCIAL PLAN 301 ANNEXURES ANNEXURE A OPERATIONAL PLAN 319 ANNEXURE B FRAMEWORK FOR PERFORMANCE 333 MANAGEMENT SYSTEM ANNEXURE C LIST OF SECTOR PLANS 334 ANNEXURE D IDP/BUDGET PROCESS PLAN FOLLOWED 337 ANNEXURE E WARD ISSUES/PRIORITIES RAISED 2018 360 ANNEXURE F PROJECTS/PROGRAMMES BY SECTOR 384 DEPARTMENTS 2 Buffalocity Metropolitan Municipality | Draft IDP Revision 2019/2020 _________________________________________________________________________________ Glossary of Abbreviations A.B.E.T. Adult Basic Education Training H.D.I Human Development Index A.D.M. Amathole District Municipality H.D.Is Historically Disadvantaged Individuals AIDS Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome H.R. Human Resources A.N.C₁ African National Congress H.I.V Human Immuno-deficiency Virus A.N.C₂ Antenatal Care I.C.D.L International Computer Drivers License A.R.T. Anti-Retroviral Therapy I.C.Z.M.P. Integrated Coastal Zone Management Plan A.S.G.I.S.A Accelerated Shared Growth Initiative of South Africa I.D.C. -

Buffalo City Municipality State of Energy Report Table of Contents

BUFFALO CITY MUNICIPALITY SSSTTTAAATTTEEE OOOFFF EEENNNEEERRRGGGYYY RRREEEPPPOOORRRTTT J28015 September 2008 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Importance of Sustainable Energy to BCM South African cities are key players in facilitating national sustainable energy policy and legislative objectives. The 15 largest cities in South Africa take up 3% of the country’s surface area, and yet they are responsible for 40% of the country’s energy consumption. This means that cities must play a major role in facilitating the achievement of national sustainable energy targets (for example the national target of 12% energy efficiency by 2014). Buffalo City, being among the nine largest cities in South Africa, and the second largest in the Eastern Cape, must ensure that it participates in, and takes responsibility for, energy issues affecting both its own population, and that of the country as a whole. Issues associated with the availability and use of energy in South Africa and the Eastern Cape are more pressing than ever before. Some of the more urgent considerations are related to the following: Climate Change: Scientific evidence shows without doubt that the earth’s atmosphere has been heating up for the past century (global warming), and that this heating is due to greenhouse gas emissions from the burning of the fossil fuels (such as coal and oil products) from which we derive our energy. Some impacts of climate change that scientists have predicted will affect Southern Africa (including BCM) are: • More disasters related to severe weather events; • Longer and drier dry periods, leading to drought; • More runaway fires; • More intense flooding; • Sea-level rise; • Threats to food security and human health; • Loss of biodiversity; • Water supply problems; and • Related economic impacts Climate change is already causing negative impacts on people and ecosystems in South Africa. -

Buffalo City Metro Municipality Socio Economic Review and Outlook, 2017

BUFFALO CITY METRO MUNICIPALITY SOCIO ECONOMIC REVIEW AND OUTLOOK, 2017 Buffalo City Metro Municipality Socio-Economic Review and Outlook 2017 Published by ECSECC Postnet Vincent, P/Bag X9063, Suite No 302, Vincent 5247 www.ecsecc.org © 2017 Eastern Cape Socio Economic Consultative Council First published April 2017 Some rights reserved. Please acknowledge the author and publisher if utilising this publication or any material contained herein. Reproduction of material in this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission from ECSECC. Buffalo City Metro Municipality Socio-Economic Review and Outlook 2017 Foreword ECSECC was founded in July 1995 as an institutional mechanism for partnership between government, business, labour and the NGO sector to address underdevelopment and poverty in the Eastern Cape. The local government sector and the higher education sector joined ECSECC in 2003. ECSECC’s mandate of stakeholder co-ordination and multi-stakeholder policy making stems from the realization that Government cannot defeat poverty, unemployment and inequality on its own, but needs to build deliberate and active partnerships to achieve prioritized development outcomes. ECSECCs main partners are: the shareholder, the Office of the Premier; national, provincial and local government; organised business and industry; organised labour; higher education; and the organised NGO sectors that make up the board, SALGA and municipalities. One of ECSECCs goals is to be a socio-economic knowledge hub for the Eastern Cape Province. We seek to actively serve the Eastern Cape’s needs to socio-economic data and analysis. As part of this ECSECC regularly issues statistical and research based publications. Publications, reports and data can be found on ECSECCs website www.ecsecc.org. -

Profile: Buffalo City

2 PROFILE: BUFFALO CITY PROFILE: BUFFALO CITY 3 CONTENT 1. Executive Summary…………………………………………………………………….3 2. Introduction: Brief Overview ............................................................................. 6 2.1 Location ..................................................................................................................................... 6 2.2 Historical Pesperctive ................................................................................................................ 6 2.3 Spatial Status ............................................................................................................................. 7 3. Social Development Profile ............................................................................... 8 3.1 Key Social Demographics ........................................................................................ 8 3.1.1 Population ............................................................................................................. 8 3.1.2 Race, Gender and Age ........................................................................................ 10 3.1.3 Households ......................................................................................................... 10 3.2 Health Profile .......................................................................................................... 11 3.3 COVID-19 .............................................................................................................. 11 3.4 Poverty Dimensions .............................................................................................. -

The Geology of the Area Around East London, Cape Province

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLlEK VAN SUID.AFRI-KA DEPARTMENT OF MINES DEPARTEMENT VAN MYNWESE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEOLOGIESE OPNAME THE GEOLOGY OF THE AREA AROUND EAST LONDON, CAPE PROVINCE AN EXPLANATION OF SHEET MAP 32270 (EAST LONDON), 3228C (KEI MOUTH) by E. D. MOUNTAIN (MA (Cantab), D.Se. Met 'n opsomming in Afrikaans onder die opskrif DIE GEOLOGIE VAN OOS-LONDEN EN OMGEWING COPYRIGHT RESERVEDjKOPIEREG VOORBEHOU 1974 PRINTED BY AND OBTAINABLE FROM THE GEDRUK DEUR EN VERKRYBAAR VAN DIE GOVERNMENT PRINTER. BOSMAN STREET. STAATSDRUKKER, BOSMANSTRAAT. PRI· PRIVATE BAG X8S, PRETORIA VAATSAK X8S, PRETORIA GEOLOGICAL MAP IN COLOUR ON A GEOLOGIESE KAART IN KlEUR OP 'N SCALE OF 1,125000 OBTAINABLE SEPA· SKAAL VAN 1,125000 APART VERKR YBAAR RATELY AT 60c, FOREIGN 7Sc . TEEN 60c, BUITELANDS 7Sc THE GEOLOGY OF THE AREA AROUND EAST LONDON, CAPE PROVINCE AN EXPLANATION OF SHEET MAP 3227D (EAST LONDON), 3228C (KEI MOUTH) ABSTRACT 0 The area is bounded by 32 30'S, 27°30'E and the coast, with East Lon don near the mid-point of the coast-line. The surface is a coastal plain rising from near sea-level to 916 m at the north-west corner and dissected by a number of rivers, chief of which are the Kei and the Buffalo. The geological formations range in age from Beaufort Series to Recent but most of the area consists of Beaufort Series invaded by Karoo dolerite. Most interesting is the recognition of the Middle Beaufort Stage at Kidd's Beach, Kwelera River, Qolora River and near Stutterheim as a characteris tic sandstone sequence 900 m thick. -

East London Education District

MKHONJANI NYABAVU MAZOTSHWENI XHOBANI QOBOQOBO SOMANA NKUKWANE GODIDI KWATHYAU NXAXHA KWANOBUSWANA GOJELA 2 4 MMANGWENI A GQUNQE QORA1 6 11 55 HECKEL KWABINASE EBHITYOLO 2 4 QIN GOBE MANUBE MANUBI 1 6 K LU MQAMBILE 11 00 SIZI LUSIZI GQUNQE Mbhashe Local Municipality ENGQANDA W S ANE A I TSIM K H A MANTETYENI N DIKHOHLONG N L WARTBURG I U LUSIZI GCINA O SEMENI NXAXHO B G O 1 4 L C GQUNQE Q N GCINA LUKHOLWENI 1 4 L HLANGANI GOBE NTILINI W A Qina Clinic G 44 O KWAMANQULU A T N R L RAWINI W I A Mgwali Clinic GOBE Z POTHLO W G 2 3 NTSHONGWENI E R Springs Clinic 2 3 NXQXHO M HLANGANI N E MGWALI GQUNQE I N V G G GCINA E I R GOBE NXAXHO B O EMAHLUBINI MAFUSINI SIGANGENI O E R O KOBODI INDUSTRIAL VIKA LE E T D CEBE CHEBE L T - LUSIZI MATEYISI GCINA E S I GQUNQE O K NCIBA GOBE I E MPHUMLANI DYOSINI KOBODI THEMBANI D I O I GODIDI R I S I T V A NJINGINI E I ER KOBODI A L 2 2 MANZAMA A R 2 2 NTINDE G I TOL E M V NI NDUVENI N E NXAXHO A N LA NDUBUNGE LUSIZI R N G Y Y X MATSHONA I LUSIZI A A O S S X T N KEI BRIDGE 66 GCINA GCINA I W A NTSANGANE H 11 R A A A Macibe Clinic ZIBUNU GQUNQE GCINA E R N S L IV ENTLEKISENI K M DLEPHU A E H KWA NGWANE COLUMBA MISSION O R U I U I MACIBE LUSIZI LU N E L B Q M SI GQ S A K Z U T I I I NQ O W U KOBODI B MACIBE E G O L MAZZEPA BAY T S G D A E M B C CI M W I Q E A B CHEBE M I KWATHALA MACIBE SINTSANA A N E U B O U NKENTE B O N N L X O N E B C E I K A K 7 Q G G MNYAMENI 7 Ngqusi Clinic U MNYAMA M U X Q KOBODI D 99 R A B MACIBE O O GQUNQE O O B U EDRAYINI BO KOMKHULU MB D L I O AZELA A O S DLEPHU B T N BUSY VILLAGE N -

Provincial Gazette / Igazethi Yephondo / Provinsiale Koerant

PROVINCE OF THE EASTERN CAPE IPHONDO LEMPUMA KOLONI PROVINSIE VAN DIE OOS-KAAP Provincial Gazette / Igazethi Yephondo / Provinsiale Koerant BHISHO/KING WILLIAM’S TOWN PROCLAMATION by the MEC for Economic Development, Environmental Affairs and Tourism January 2020 1. I, Mlungisi Mvoko, Member of the Executive Council (MEC) for Economic Development, Environmental Affairs and Tourism (DEDEAT), acting in terms of Sections 78 and 79 of the Nature and Environmental Conservation Ordinance, 1974 (Ordinance No. 19 of 1974), and Section 18 of the Problem Animal Control Ordinance, 1957 (Ordinance 26 of 1957) hereby determine for the year 2020 the hunting season and the daily bag limits, as set out in the second and third columns, respectively, of Schedule 1, hereto in the Magisterial Districts of the Province of the Eastern Cape of the former Province of the Cape of Good Hope and in respect of wild animals mentioned in the first column of the said Schedule 1, and I hereby suspend and set conditions pertaining to the enforcement of Sections 29 and 33 of the said Ordinance to the extent specified in the fourth column of the said Schedule 1, in the district and in respect of the species of wild animals and for the periods of the year 2020 indicated opposite any such suspension and/or condition, of the said Schedule 1. 2. In terms of Section 29 (e), [during the period between one hour after sunset on any day and one hour before sunrise on the following day], subject to the provisions of this ordinance, I prohibit hunting at night under the following proviso, that anyone intending to hunt at night for management purposes by culling any of the Alien and Invasive listed species, Hares, specified species, Rodents, Porcupine, Springhare or hunting Black-backed jackal, Bushpig and Caracal, in accordance with the Ordinance, must apply to DEDEAT for a provincial permit and must further notify the relevant DEDEAT office, and where applicable the SAPS Stock Theft Unit, during office hours, prior to such intended hunt. -

2016 Long Term Grazing Capacity (Ha/LSU) - Eastern Cape

2016 Long Term Grazing Capacity (ha/LSU) - Eastern Cape " " " " " " " " " " 16 Kraankuil Richmond " 10 5 Ndaleni" 7 Donnybrook " Strydenburg " " N 6 7 3.5 / Van Stadensrus 7 " 3.5 F 4.5 14 Trompsburg R Creighton " E 7 3 " E Petrusville 9 7 W Riverside " A 6 Y " 13 Ixopo 6.5 Sodium 11 5 " 24 " E Potfontein 8 8 4.5 5 T " Smithfield 4 U 11 " 3.5 4 O 15 Philippolis 4 Highflats R Springfontein uMzimkulu " 12 " N " " L 6/ Zastron 6 5 A 5 Clydesdale 13 F 7 " Franklin " N R 4 Matatiele 2 " 3 " O E 7 I E " 6 T W A 11 A 9 Y 3.5 Cedarville N Y " A 10 8 Rouxville4 Bisi 2 W 10 " Seqhobong " 1 Philipstown E " 4.5 5 N " 15 E 3 5 20 R 9 5 Kinira Drift 5 5.5 F Rietvlei 3 Bethulie " " /1 " 4.5 5 1 12 8 Sterkspruit 9 2 St Faiths N 7 " Kokstad " " Vosburg Britstown L 6 12 2.5 Weza " " IONA Oranjekrag " " NAT " 15 Herschel 8 N1 " 3 4 Harding 9 De Aar " 8 8 3.5 4 " Norvalspont 11 8 6 Oviston " " 3 3 N Colesberg " 9 Lady Grey 1 " " 0 Aliwal North 12 Mount Fletcher " N 6 5 A AY T W Venterstad iZingolweni IO EE 15 " Rhodes Elands Heights Mount Ayliff " N R 7 " " A F 4 5 " L AL 8 R N Margate O IO 5 Bizana " T E 9 4 " U A 6 Mount Frere T 1 N T " E N U O 6 Halcyon Drift Hanover Road R 5 " Barkly East " 6 5 Tabankulu 3 L " 5 " A Burgersdorp Floukraal 6 Munster " N " " " " O 13 13 8 4 18 I 6 5 Deelfontein T Clanville Port Edward Hanover A Maclear Flagstaff " N " 6 " " 9 10 4.5 4.5 5 16 N Jamestown " 5 3 14 6 Qumbu Noupoort 13 7 " " " Ugie Merriman Rossouw " 4.5 " 7 6 26 20 6 Steynsburg Stormberg Mkambati " " Tsolo " Elliot " 16 6 " 5 7 Dordrecht Lusikisiki Victoria -

The Centenary of the Synod 1895-1995 by Reino

EVANGELICAL LUTHERAN CHURCH IN SOUTHERN AFRICA (CAPE CHURCH) The Centenary of the Synod 1895-1995 by Reino Ottermann CAPE TOWN 1995 1 Reino Ottermann: The Centenary of the Synod 1895-1995 (Cape Town 1995) Index of Subjects Errata in the printed text: p 17, line 6: 21 May 1872 (not 1879) photo before p 33: Bishop Nils Rohwer, Bishop since 1991 (not 1989) p 69: Mrs R. Pakleppa (not Mr) p 116, King William’s Town 1883: Dr J.M. Zahn (not T.M.) p 124, Welkom 1958-1959: Pastor U. Duschat (not P. Duschat) p.127, par. 1: Delete the last part of the second sentence, “ ... probably the second, enlarged edition of 1856.” Additions: pp 30 & 120: Pastor F. Grussendorf p 92, 1907-1908: Diakon David Behrens P 109, Rev. Rudolph B. von Hube Subsequent to the publication of the book in 1995, I finally managed (in May 1999) to find, in the archives of the Berlin Mission in Berlin, important documents pertaining to the events preceding the founding of the Synod in 1895. Apart from a considerable amount of interesting correspondence between pastors in the Border Area, the Berlin Mission and the Church of Hanover, the most important documents are copies of the minutes of the pastors’ conferences in East London on 27 February 1883 and 19 May (not 20 May) 1885 to which I refer on pp 17 to 20. My only source of information before publication in 1995 were two articles by Pastor J Spanuth in Südafrikanisches Gemeindeblatt of 28 May and 11 June 1909. Spanuth must have had access to the original minutes which, I assume, were subsequently lost. -

Vegetation Units

GOLDEN GATE HIGHLANDS N P QWAQWA NATIONAL PARK Gh7 Gh6 Gm4 Gd5 Gs4 SVl23 MTUBATUBA GREATER ST LUCIA AZi10 SVk5 Gh6 Gh7 Gd8 Gd8 Gm4 Gd8 Gs3 Gs6 SVs2 Gs4 SVs2 FOz5 RIVER VIEW AZi10 Gd5 Gd8 Gd5 Gs7 Gs6 WETLAND PARK DEALESVILLE FOURIESBURG LADYSMITH Gs4 POMEROY i AT 11 Great Fish Thicket AZi10 VAALBOS AZi10 Gh10 Gh8 Gh7 SVs1 Gd6 SVk5 AZf3 Gm5 Gs4 Mfoloz SVk5 NATIONAL PARK Gs4 Gs3 SVl24 FOa3 AZs3 SOUTPAN MARQUARD AZf3 AZf3 SVl22 SVl22 SCHMIDTSDRIF AZi10 BRANDFORT Gm5 Gs6 Gs4 Gs6 MELMOTH Gm4 UKHAHLAMBA SVs2 QUDENI AZd4 AT 12 Buffels Thicket SVk5 SVk5 Gh7 Gs5 SVl22 SVk4 Gm5 DRAKENSBERG PARK SVs2 Gs4 SVs4 CB1 FOz7 Soutpan Gh9 Gm3 Gd10 SVs2 Gs9 NKANDLA Gh7 FOz2 Gs3 AZf6 KIMBERLEY AZi10 Gh9 AZi10 Gh10 Gm4 Gd5 Woodstock SVs1 FOz3 FOz7 AT 13 Eastern Cape Escarpment Thicket AZi10 AZi10 Gh8 Gm4 Gd8 Gd7 Dam Spioenkop Dam FOz3 AZi10 SVs2 FOz3 SVk5 AZi10 SOETDORING Gh8 Gm5 AZf3 BERGVILLE WOLWEDRIFT Gm4 on Gs4 KWA MBONAMBI AZa5 AZf3 BUTHA BUTHE Gm5 SVs4 SVs4 SVl23 AT 14 Camdebo Escarpment Thicket AZi10 Gh10 Gh6 Gd6 TUGELA FERRY FOz5 NSELENI AZd4 Gm5 o COLENSO CB2 NKu3 Caled Gm4 AZf5 SVs1 SVk5 M VERKEERDEVLEI s SVl24 AZs3 AZi10 o ALLANDALE HLOTSE t Nkandla Gh5 d a Gs6 SVs4 NKWALINI FOz7 FOa2 SVk4 d Gm4 Forest Krugersdrif Dam Gm4 m FOz2 SVs1 CB1 FOz7 e Gm4 Gs10 Gh8 a WINTERTON z r FICKSBURG tu e SVk5 b JAMESON´S DRIFT CB1 SVk5 AZa5 EXCELSIOR i la AZi10 Gh8 Gh6 l M h EMPANGENI AZi10 a SVk5 AZi10 Gd6 Gs4 WEENEN KEATE´S DRIFT Gs6 SVs6 FOa2 FOz7 AZa4 NKu3 AZi10 Gh8 Gh7 CLOCOLAN M et SVk5 Gm5 SVs2 Ri AZi10 AZi10 Gm3 Gd10 Gd6 FOz2 Gs6 SVs3 AZf6 o Gh5 Gh5 Gm4 TS'EHLANYANE -

Access to the SG Approved and Registered Cadastre

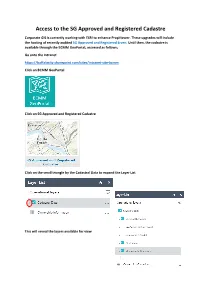

Access to the SG Approved and Registered Cadastre Corporate GIS is currently working with ESRI to enhance PropViewer. These upgrades will include the hosting of recently audited SG Approved and Registered Erven. Until then, the cadastre is available through the BCMM GeoPortal, accessed as follows; Go onto the Intranet https://buffalocity.sharepoint.com/sites/intranet-site-bcmm Click on BCMM GeoPortal Click on SG Approved and Registered Cadastre Click on the small triangle by the Cadastral Data to expand the Layer List This will reveal the layers available for view Property searches can be done using the search tool in the top left corner Start the search by either typing the prefix and first 6 digits of an LPKey, or Address or Name of Sectional Scheme eg; Result Black Lines represent Registered Erven, Red Lines are SG Approved and Pink Hexagons represent Sectional Schemes. Items in the Layer List can be expanded by clicking on the small black triangles on each line. Layers can be turned on and off, simply by clicking on the green squares alongside each layer name LP Key Searches – (Prefix and first 6 digits, starting with zero’s – 3, for a 3-digit erf number, 2 for a 4 digit number etc. Result . An LPKEY comprises of an 18-digit number, but when doing a search, one must only know the prefix (3 letters) and the erf number, which is preceded by zero’s depending on the number of digits in the erf number to total up to 6 digits. The table below shows, as an example, how an LPKEY for Erf 351 in Beacon Bay is constructed. -

Premier Resort Mpongo Private Game Reserve

PREMIER RESORT MPONGO PRIVATE GAME RESERVE LOCATION ACCOMMODATION Situated 35km from East London, HUBERTA LODGE INDLOVU LODGE along the tarred and well signposted 1 x Deluxe Room 1 Family Room N6 national road to Stutterheim, 5 x Standard Rooms 19 x Deluxe Rooms and 40km from East London • Communal lounge 2 x Dormitories Airport. An easy drive into town for • Hairdryer • Communal lounge shopping, entertainment or to take • Tea & Coffee Facilities • Tea & Coffee Facilities in the area’s spectacular coastline • Dining room and endless sandy beaches, if you RIVER LODGE • Pool • Hairdryer want to combine big game with big 3 x Two-bedroom Chalets surf. Mpongo Private Game Reserve 1 x Suite UMTHOMBE offers a unique blend of luxury and 10 x Deluxe Rooms BUSH VILLA - SINGLE VILLA game viewing experiences on more 3 x King Rooms than 3500 ha of conservation land in • All offering en-suite bathrooms 2 x Twin Rooms spectacular surroundings. • Tea & coffee facilities • Pool • Lapa • Hairdryer • Dining room • Communal lounge PROPERTY DESCRIPTION • Communal lounge • Tea & Coffee Facilities • • Fireplace Fireplace • Pool • Hairdryer Macleantown, Eastern Cape Bushveld 44.5 km - East London 46.5 km - East London Airport Conference Restaurant Ladies Bar On-site parking facilities Game Drives Guided Hikes Wake-up call LEISURE FACILITIES AND ATTRACTIONS Open vehicle game drives and guided walks by experienced game rangers are an incredible way to experience the diversity of wildlife on the reserve. Sunset drives and night drives, with cocktail, braai and picnic set ups are firm favourites for conference groups and are based on sufficient guest participation. The reserve is home to big game, including lions, elephant, buffalo, giraffe, numerous antelope species and 225 bird species including birds of prey – making it a popular destination for universities and birding enthusiasts.