A Socio-Historical and Political Discourse on the Rights of Muslim

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Population According to Religion, Tables-6, Pakistan

-No. 32A 11 I I ! I , 1 --.. ".._" I l <t I If _:ENSUS OF RAKISTAN, 1951 ( 1 - - I O .PUlA'TION ACC<!>R'DING TO RELIGIO ~ (TA~LE; 6)/ \ 1 \ \ ,I tin N~.2 1 • t ~ ~ I, . : - f I ~ (bFICE OF THE ~ENSU) ' COMMISSIO ~ ER; .1 :VERNMENT OF PAKISTAN, l .. October 1951 - ~........-.~ .1',l 1 RY OF THE INTERIOR, PI'ice Rs. 2 ~f 5. it '7 J . CH I. ~ CE.N TABLE 6.-RELIGION SECTION 6·1.-PAKISTAN Thousand personc:. ,Prorinces and States Total Muslim Caste Sch~duled Christian Others (Note 1) Hindu Caste Hindu ~ --- (l b c d e f g _-'--- --- ---- KISTAN 7,56,36 6,49,59 43,49 54,21 5,41 3,66 ;:histan and States 11,54 11,37 12 ] 4 listricts 6,02 5,94 3 1 4 States 5,52 5,43 9 ,: Bengal 4,19,32 3,22,27 41,87 50,52 1,07 3,59 aeral Capital Area, 11,23 10,78 5 13 21 6 Karachi. ·W. F. P. and Tribal 58,65 58,58 1 2 4 Areas. Districts 32,23 32,17 " 4 Agencies (Tribal Areas) 26,42 26,41 aIIjab and BahawaJpur 2,06,37 2,02,01 3 30 4,03 State. Districts 1,88,15 1,83,93 2 19 4,01 Bahawa1pur State 18,22 18,08 11 2 ';ind and Kbairpur State 49,25 44,58 1,41 3,23 2 1 Districts 46,06 41,49 1,34 3,20 2 Khairpur State 3,19 3,09 7 3 I.-Excluding 207 thousand persons claiming Nationalities other than Pakistani. -

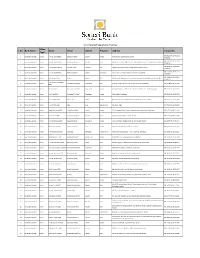

S. No. Bank Name Office Type* Name Tehsil District Province Address

List of Selected Operational Branches Office S. No. Bank Name Name Tehsil District Province Address License No. Type* BRL-20115 dt: 19.02.2013 1 Soneri Bank Limited Branch Main Br. Lahore-0001 Lahore City Tehsil Lahore Punjab 87, Shahrah-E-Quaid-E-Azam, Lahore (Duplicate) BRL-20114 dt: 19.02.2013 2 Soneri Bank Limited Branch Main Br. Karachi-0002 Karachi South District Karachi Sindh Plot No: Sr-2/11/2/1, Office No: 105-108, Al-Rahim Tower, I.I. Chundrigar Road, Karachi (Duplicate) BRL-20116 dt: 19.02.2013 3 Soneri Bank Limited Branch Main Branch Peshawar Peshawar Tehsil Peshawar KPK Property No: Ca/457/3/2/87, Saddar Road, Peshawar Cantt., (Duplicate) BRL-20117 dt: 19.02.2013 4 Soneri Bank Limited Branch Main Br. Quetta-0004 Quetta City Tehsil Quetta Balochistan Ground Floor, Al-Shams Hotel, M.A. Jinnah Road, Quetta. (Duplicate) BRL-17606 dt: 03.03.2009 5 Soneri Bank Limited Branch Main Branch Mirpur Mirpur Mirpur AJK Plot No: 35/A, Munshi Sher Plaza, Allama Iqbal Road, New Mirpur Town, Mirpur (Ak) (Duplicate) Main Branch, Hyderabad.- 6 Soneri Bank Limited Branch Hyderabad City Taluka Hyderabad Sindh Shop No: 6, 7 & 8, Plot No: 475, Dr. Ziauddin Road, Hyderabad BRL-13188 dt: 04.04.1993 0006 7 Soneri Bank Limited Branch Main Guj-0007 Gujranwala City Tehsil Gujranwala Punjab Khewat & Khatooni: 78 Khasra No: 393 Near Din Plaza G. T. Road Gujranwala BRL-13192 dt: 14.07.1993 8 Soneri Bank Limited Branch Main Fsd-0008 Faisalabad City Tehsil Faisalabad Punjab Chiniot Bazar, Faisalabad BRL-13196 dt: 30.09.1993 9 Soneri Bank Limited Branch Sie Br. -

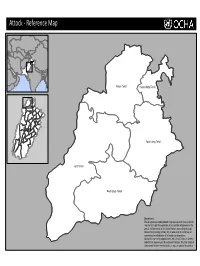

Reference Map

Attock ‐ Reference Map Attock Tehsil Hasan Abdal Tehsil Punjab Fateh Jang Tehsil Jand Tehsil Pindi Gheb Tehsil Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. Bahawalnagar‐ Reference Map Minchinabad Tehsil Bahawalnagar Tehsil Chishtian Tehsil Punjab Haroonabad Tehsil Fortabbas Tehsil Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. p Bahawalpur‐ Reference Map Hasilpur Tehsil Khairpur Tamewali Tehsil Bahawalpur Tehsil Ahmadpur East Tehsil Punjab Yazman Tehsil Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Division KARACHI

Division KARACHI Sr. No Name Address Latitude Longitude 1 IQBAL F/S AND CNG PLOT NO.59, KAYANI SHAHEED ROAD, KARACHI 24.867644 67.024863 2 COCO - PSO S/S 7 (A.B GHAZI) ABDULLAH SHAH GHAZI CLIFTON, KARACHI 24.80731 67.03665 3 STANDARD SERVICE STN 17-A BLOCK 6 P.E.C.H.S KARACHI 24.8612387 67.0645786 4 RAZI SERVICE STATION PLOT-P-13 BLOCK-16 GULSHAN-E-IQBAL 24.90608 67.08102 5 AL-MADINA SER.STN ST-2 BLOCK 4, SECTOR 5 NORTH KARACHI KARACHI 24.988439 67.064916 6 NOORANI PETROLEUM SER THATTA DISTT THATTA 24.75163 67.92008 7 MOON STAR SER.STATIONS ECTOR 21 PLOT ST-2 KORANGI INDUST.AREA KARACHI 24.8515359 67.1826475 8 COCO - MG Motors PLOT NO. NO. 32/1, FT-3, FRERE TOWN QUARTER, NEAR PSO HOUSE KARACHI 24.835714 67.034006 9 SHAHEEN SERVICE STATION NEAR AIRPORT POLICE STATION, SHAHRAH-E-FAISAL, KARACHI 24.8871 67.14576 10 STADIUM SERVICE STATION PLOT NO: ST-10/B, ADJACENT AGHA KLHAN HOSPITAL, MAIN STADIUM ROAD , KARACHI 24.89115 67.07743 11 YOUSUFI SERVICE STN PLOT 26 ON NUSRAT BHUTTO ROAD AT DEH MANGHOPIR KARACHI 24.968813 67.041152 12 MACCA MOBILE SER. 1036M.A.JINNAH ROAD KARACHI 24.88372 67.05521 13 SHAHZAD T/S. 15/2 NATIONAL HIGHWAY KARACHI 24.85484 67.23238 14 ARABIAN S/S. ST 1/9 SET 15 KORANGI TOWNSHIP KARACHI 24.8394604 67.1197356 15 A. REHMAN PETROLEUM, S'H'W Plot # 58/2-13 Deh Tore Tappo 27 / 28 km Super Highway 24.986655 67.206554 16 MEHDI F/S. -

Prequalification Document for WAN Connectivity Services (Primary & Backup) for PLRA Arazi Record Centers (Arcs) in Punjab

Prequalification Document for WAN Connectivity Services (Primary & Backup) for PLRA Arazi Record Centers (ARCs) in Punjab Procurement ID: PLRA/PROC/WAN/2020 Punjab Land Records Authority, Board of Revenue, Govt of the Punjab Sep 2020 The Punjab Land Records Authority (PLRA) intends to pre-qualify reputed firms in accordance with Rule 16 of PPR-2014 for the WAN Connectivity Services (Primary & Backup) for 151 PLRA ARCs, 115 Qanungoi Sites & 145 ROD Sites, Aggregation and Services Links and Software Defined WAN (SD-WAN) Solution. Interested bidders may obtain Pre-qualification document from this office during office working hours against submission of application along with bank deposit receipt of PKR 1000/- in PLRA CPA Account 6580036040700018, Branch Code 0330 of Bank of Punjab, immediately after publication of advertisement. The response, complete in all respect, must reach this office on or before 29.09.2020 at 11:00 a.m. which shall be opened on the same day at 11:30 a.m. in the presence of authorized representatives of applicant firms, who choose to attend. Any response received after the scheduled time shall not be entertained and would be returned unopened. The Pre-qualification notice and document are available on the PPRA & PLRA websites. Bidders may obtain further information by sending email to ‘[email protected]’ or by contacting at below mentioned address. Dy. Director (Procurement), PLRA 2 km, Thokar Niaz Baig Bypass, Main Multan Road, Lahore 042-99330125-26 (Ext 212), Fax 042-99330127 Web: www.punjab-zameen.gov.pk Terms of Reference 1. Background Punjab Land Records Authority (PLRA) has established 152x Arazi Record Centers across the province for Mutation and Fard issuance. -

S.R.O. No.---/2011.In Exercise Of

PART II] THE GAZETTE OF PAKISTAN, EXTRA., JANUARY 9, 2021 39 S.R.O. No.-----------/2011.In exercise of powers conferred under sub-section (3) of Section 4 of the PEMRA Ordinance 2002 (Xlll of 2002), the Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority is pleased to make and promulgate the following service regulations for appointment, promotion, termination and other terms and conditions of employment of its staff, experts, consultants, advisors etc. ISLAMABAD SATURDAY, JANUARY 9, 2021 PART II Statutory Notifications (S. R. O.) GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN MINISTRY OF NATIONAL FOOD SECURITY AND RESEARCH NOTIFICATION Islamabad, the 6th January, 2021 S. R. O. (17) (I)/2021.—In exercise of the powers conferred by section 15 of the Agricultural Pesticides Ordinance, 1971 (II of 1971), and in supersession of its Notifications No. S.R.O. 947(I)/2002, dated the 23rd December, 2002, S.R.O. 1251 (I)2005, dated the 15th December, 2005, S.R.O. 697(I)/2005, dated the 28th June, 2006, S.R.O. 604(I)/2007, dated the 12th June, 2007, S.R.O. 84(I)/2008, dated the 21st January, 2008, S.R.O. 02(I)/2009, dated the 1st January, 2009, S.R.O. 125(I)/2010, dated the 1st March, 2010 and S.R.O. 1096(I), dated the 2nd November, 2010. The Federal Government is pleased to appoint the following officers specified in column (2) of the Table below of Agriculture Department, Government of the Punjab, to be inspectors within the local limits specified against each in column (3) of the said Table, namely:— (39) Price: Rs. -

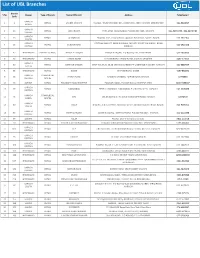

To Download UBL Branch List

List of UBL Branches Branch S No Region Type of Branch Name Of Branch Address Telephone # Code KARACHI 1 2 RETAIL LANDHI KARACHI H-G/9-D, TRUST CERAMIC IND., LANDHI IND. AREA KARACHI (EPZ) EXPORT 021-5018697 NORTH KARACHI 2 19 RETAIL JODIA BAZAR PARA LANE, JODIA BAZAR, P.O.BOX NO.4627, KARACHI. 021-32434679 , 021-32439484 CENTRAL KARACHI 3 23 RETAIL AL-HAROON Shop No. 39/1, Ground Floor, Opposite BVS School, Sadder, Karachi 021-2727106 SOUTH KARACHI CENTRAL BANK OF INDIA BUILDING, OPP CITY COURT,MA JINNAH ROAD 4 25 RETAIL BUNDER ROAD 021-2623128 CENTRAL KARACHI. 5 47 HYDERABAD AMEEN - ISLAMIC PRINCE ALLY ROAD PRINCE ALI ROAD, P.O.BOX NO.131, HYDERABAD. 022-2633606 6 46 HYDERABAD RETAIL TANDO ADAM STATION ROAD TANDO ADAM, DISTRICT SANGHAR. 0235-574313 KARACHI 7 52 RETAIL DEFENCE GARDEN SHOP NO.29,30, 35,36 DEFENCE GARDEN PH-1 DEFENCE H.SOCIETY KARACHI 021-5888434 SOUTH 8 55 HYDERABAD RETAIL BADIN STATION ROAD, BADIN. 0297-861871 KARACHI COMMERCIAL 9 65 NAPIER ROAD KASSIM CHAMBERS, NAPIER ROAD,KARACHI. 32775993 CENTRAL CENTRE 10 66 SUKKUR RETAIL FOUJDARY ROAD KHAIRPUR FOAJDARI ROAD, P.O.BOX NO.14, KHAIRPUR MIRS. 0243-9280047 KARACHI 11 69 RETAIL NAZIMABAD FIRST CHOWRANGI, NAZIMABAD, P.O.BOX NO.2135, KARACHI. 021-6608288 CENTRAL KARACHI COMMERCIAL 12 71 SITE UBL BUILDING S.I.T.E.AREA MANGHOPIR ROAD, KARACHI 32570719 NORTH CENTRE KARACHI 13 80 RETAIL VAULT Shop No. 2, Ground Floor, Nonwhite Center Abdullah Harpoon Road, Karachi. 021-9205312 SOUTH KARACHI 14 85 RETAIL MARRIOT ROAD GILANI BUILDING, MARRIOT ROAD, P.O.BOX NO.5037, KARACHI. -

(Primary & Backup) for PLRA Arazi Record Centers (Arcs) in Punjab

Prequalification Document for WAN Connectivity Services (Primary & Backup) for PLRA Arazi Record Centers (ARCs) in Punjab Procurement ID: PLRA/PROC/WAN/2020 Punjab Land Records Authority, Board of Revenue, Govt of the Punjab Sep 2020 The Punjab Land Records Authority (PLRA) intends to pre-qualify reputed firms in accordance with Rule 16 of PPR-2014 for the WAN Connectivity Services (Primary & Backup) for 151 PLRA ARCs, 115 Qanungoi Sites & 145 ROD Sites, Aggregation and Services Links and Software Defined WAN (SD-WAN) Solution. Interested bidders may obtain Pre-qualification document from this office during office working hours against submission of application along with bank deposit receipt of PKR 1000/- in PLRA CPA Account 6580036040700018, Branch Code 0330 of Bank of Punjab, immediately after publication of advertisement. The response, complete in all respect, must reach this office on or before 18.09.2020 at 11:00 a.m. which shall be opened on the same day at 11:30 a.m. in the presence of authorized representatives of applicant firms, who choose to attend. Any response received after the scheduled time shall not be entertained and would be returned unopened. The Pre-qualification notice and document are available on the PPRA & PLRA websites. Bidders may obtain further information by sending email to ‘[email protected]’ or by contacting at below mentioned address. Dy. Director (Procurement), PLRA 2 km, Thokar Niaz Baig Bypass, Main Multan Road, Lahore 042-99330125-26 (Ext 212), Fax 042-99330127 Web: www.punjab-zameen.gov.pk Terms of Reference 1. Background Punjab Land Records Authority (PLRA) has established 152x Arazi Record Centers across the province for Mutation and Fard issuance. -

Province Wise Provisional Results of Census - 2017

PROVINCE WISE PROVISIONAL RESULTS OF CENSUS - 2017 ADMINISTRATIVE UNITS POPULATION 2017 POPULATION 1998 PAKISTAN 207,774,520 132,352,279 KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA 30,523,371 17,743,645 FATA 5,001,676 3,176,331 PUNJAB 110,012,442 73,621,290 SINDH 47,886,051 30,439,893 BALOCHISTAN 12,344,408 6,565,885 ISLAMABAD 2,006,572 805,235 Note:- 1. Total Population includes all persons residing in the country including Afghans & other Aliens residing with the local population 2. Population does not include Afghan Refugees living in Refugee villages 1 PROVISIONAL CENSUS RESULTS -2017 KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA District Tehsil POPULATION POPULATION ADMN. UNITS / AREA Sr.No Sr.No 2017 1998 KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA 30,523,371 17,743,645 MALAKAND DIVISION 7,514,694 4,262,700 1 CHITRAL DISTRICT 447,362 318,689 1 Chitral Tehsil 278,122 184,874 2 Mastuj Tehsil 169,240 133,815 2 UPPER DIR DISTRICT 946,421 514,451 3 Dir Tehsil 439,577 235,324 4 *Shringal Tehsil 185,037 104,058 5 Wari Tehsil 321,807 175,069 3 LOWER DIR DISTRICT 1,435,917 779,056 6 Temergara Tehsil 520,738 290,849 7 *Adenzai Tehsil 317,504 168,830 8 *Lal Qilla Tehsil 219,067 129,305 9 *Samarbagh (Barwa) Tehsil 378,608 190,072 4 BUNER DISTRICT 897,319 506,048 10 Daggar/Buner Tehsil 355,692 197,120 11 *Gagra Tehsil 270,467 151,877 12 *Khado Khel Tehsil 118,185 69,812 13 *Mandanr Tehsil 152,975 87,239 5 SWAT DISTRICT 2,309,570 1,257,602 14 *Babuzai Tehsil (Swat) 599,040 321,995 15 *Bari Kot Tehsil 184,000 99,975 16 *Kabal Tehsil 420,374 244,142 17 Matta Tehsil 465,996 251,368 18 *Khawaza Khela Tehsil 265,571 141,193 -

Page 1 of 44 S. No. Region Branch Code Branch Name Branch

S. No. Region Branch code Branch Name Branch Address Branch Status 1 BAHAWALPUR 0102 BAHAWALPUR-FARID GATE Property # 1612/5 B-Iv Farid Gate Circular Road Bahawalpur Open 2 BAHAWALPUR 0105 CHISHTIAN-GHALLA MAN Shop # 38/B Ghalla Mandi Chishtian District Bahawalnagar Open 3 BAHAWALPUR 0160 RAHIM YAR KHAN-SHAHI Shop # 25-26 Shahi Road Rahim Yar Khan Open 4 BAHAWALPUR 0171 KHANPUR-GHALLA MANDI Shop # 37/38 Ghalla Mandi Khanpur District Rahim Yar Khan Open 5 BAHAWALPUR 0244 BAHAWAL NAGAR-GHALLA Ghalla Mandi Branch Near Sutlej Park Chowk, Kuchery Road. Bahawalnagar Open 6 BAHAWALPUR 0285 TATAR CHACHAR Chowk Zahirpir Tehsil Khanpur Distt Rahim Yar Khan Open 7 BAHAWALPUR 0334 SADIQABAD-GOTH JURRA Khata # 180/179 Khatooni # 419 Hospital Road Goth Jurrah Sadiqabad Distt Rahim Open 8 BAHAWALPUR 0350 BAHAWALPUR-QUAID-E-A Quaid-E-Azam Medical College Circular Road Bahawalpur Open 9 BAHAWALPUR 0446 SADIQABAD-GHALLA MAN Khata # 154/154 Ward 24/B 25/B Ghalla Mandi Main Road Sadiq Abad District Rah Open 10 BAHAWALPUR 0468 YAZMAN-MAIN BRANCH Plot # 25*60 Main Road Bahawalpur Yazman District Bahawalpur Open 11 BAHAWALPUR 0469 HAROONABAD-GHALLA MA Shop # 69/C Ghalla Mandi Haroonabad Distt Bahawalnagar Open 12 BAHAWALPUR 0498 HASILPUR-BALDIA ROAD Plot No 98/C Baldia Road Hasilpur Distt Bahawalpur Open 13 BAHAWALPUR 0677 BAHAWAL NAGAR-TEHSIL Chowk Rafique Shah Bahawalnagar Open 14 BAHAWALPUR 0826 AHMEDPUR EAST-KUTCHE B-Vi-371/55- C/1 Kutchery Road Ahmed Pur East District Bahawalpur Open 15 BAHAWALPUR 0835 BHUNG Hbl Near Gool Chowk Bhung Tehsil Sadiqabad District -

Punjab Development Statistics

2007 Punjab Development Statistics BUREAU OF STATISTICS GOVERNMENT OF THE PUNJAB LAHORE PREFACE Punjab Development Statistics is a annual publication of the Punjab Bureau of Statistics which is being issued regularly since 1972. The present edition is the 33rd in the series. It provides important Statistics in respect of Social, Economic and Financial sectors of the economy at aggregate as well as sectoral levels. This publication contains data on almost all sectors of the Provincial economy with their break-up by Tehsil and District as far as possible. It also includes some national data on important subjects like Major Crops, Foreign Trade, Labour Force & Employment, National Accounts, Population, Prices and Transport etc. It also contains a “Statistical Abstract’ which gives a comparative picture of information on almost all Socio-economic Sectors of Pakistan and the Punjab. Every effort has been made to include the latest available data in this publication. It is hoped that this publication will be usefull to the policy makers, planners, researchers, Nazims, DCOs. and other data users of public as well as private sectors. I am thankful to various Provincial Departments/Agencies/Federal Ministries/Divisions for supplying the required data to the Bureau of Statistics. Without their help, it would not have been possible to release this publication in time. I would also like to thank Dr. Shujat Ali, Chief Economist, Planning and Development Department for his able leadership and the staff members of the Punjab Bureau of Statistics for their invaluable support and hard work to bring out this report. We will welcome suggestions for further improvement. -

Learning in Public Schools

Working paper Learning in Public Schools Tahir Andrabi Sohaib Khan Yasir Khan Muhammad Farooq Naseer June 2012 When citing this paper, please use the title and the following reference number: F-37021-PAK-1 Learning in Public Schools Tahir Andrabi Pomona College Sohaib Khan Lahore University of Management Sciences Yasir Khan International Growth Center Muhammad Farooq Naseer Lahore University of Management Sciences TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ..............................................................................................................................4 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................5 Analysis of PEC Data ...........................................................................................................................7 Variation in School Achievement.....................................................................................................7 School-level Factors ..................................................................................................................... 11 Correlates of School Achievement................................................................................................. 13 Research on Learning Achievement ................................................................................................... 15 Continuous Professional Development (CPD) Framework.................................................................... 18 Professional Needs