Reaping the Rewards of the Reading for Understanding Initiative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

URL 100% (Korea)

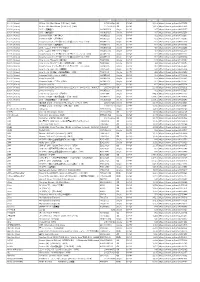

アーティスト 商品名 オーダー品番 フォーマッ ジャンル名 定価(税抜) URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤C> OKCK5022 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732096 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤B> OKCK5021 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732095 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (チャンヨン)(LTD) OKCK5017 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655033 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤A> OKCK5020 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732093 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ジョンファン)(LTD) OKCK5016 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655032 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ヒョクジン)(LTD) OKCK5018 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655034 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 Single K-POP 421 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 -

Bab Ii “Menarikan Sang Liyan” : Feminisme Dalam Industri Musik

BAB II “MENARIKAN SANG LIYAN”i: FEMINISME DALAM INDUSTRI MUSIK “A feminist approach means taking nothing for granted because the things we take for granted are usually those that were constructed from the most powerful point of view in the culture ...” ~ Gayle Austin ~ Bab II akan menguraikan bagaimana perkembangan feminisme, khususnya dalam industri musik populer yang terepresentasikan oleh media massa. Bab ini mempertimbangkan kriteria historical situatedness untuk mencermati bagaimana feminisme merupakan sebuah realitas kultural yang terbentuk dari berbagai nilai sosial, politik, kultural, ekonomi, etnis, dan gender. Nilai-nilai tersebut dalam prosesnya menghadirkan sebuah realitas feminisme dan menjadikan realitas tersebut tak terpisahkan dengan sejarah yang telah membentuknya. Proses historis ini ikut andil dalam perjalanan feminisme from silence to performance, seperti yang diistilahkan Kroløkke dan Sørensen (2006). Perempuan berjalan dari dalam diam hingga akhirnya ia memiliki kesempatan untuk hadir dalam performa. Namun dalam perjalanan performa ini perempuan membawa serta diri “yang lain” (Liyan) yang telah melekat sejak masa lalu. Salah satu perwujudan performa sang Liyan ini adalah industri musik populer K-Pop yang diperankan oleh perempuan Timur yang secara kultural memiliki persoalan feminisme yang berbeda dengan perempuan Barat. 75 76 K-Pop merupakan perjalanan yang sangat panjang, yang mengisahkan kompleksitas perempuan dalam relasinya dengan musik dan media massa sebagai ruang performa, namun terjebak dalam ideologi kapitalisme. Feminisme diuraikan sebagai sebuah perjalanan “menarikan sang Liyan” (dancing othering), yang memperlihatkan bagaimana identitas the Other (Liyan) yang melekat dalam tubuh perempuan [Timur] ditarikan dalam beragam performa music video (MV) yang dapat dengan mudah diakses melalui situs YouTube. Tarian merupakan sebuah bentuk konsumsi musik dan praktik kultural yang membawa banyak makna tersembunyi mengenai konteks sosial (Wall, 2003:188). -

Rnvymimu Ooimtmrni^Iim

o 0 <N 1 o00 o GS rnVYmiMu1 / OoimtMrni^iiM u ' r . •liivi • .V . 'Ifyly I • • . • -.u- - I..-. ^ • /•• • --v.: i . •IM. ''•J (presicCency CoCCege Magazine (VOLUME 69) 2008-2009 MAGAZINE COMMIHEE "Though wifcf-waves roCC Between us now" [ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS] • Sanjib Ghosh (Principal) • Devasish Sen (Bursar) • Sanjib Ghosh (Principal) • Sanghita Sen (Teacher in Charge (Bursar) • Devasish Sen of Publications) • Sanghita Sen (Teacher in Charge of Publications) Swanap Kumar De Niranjan Goswami (Teacher Editors) Swanap Kumar De Himanshu Kumar Niranjan Goswami (Teacher Editors) Himanshu Kumar Anitesh Chakraborty (General Editors) Sreecheta Das Debrarayan Chakrabarti (Senior Librarian) Dinanath Singh (Editor, Hindi Section) Bijoy De (Librarian) Swapon Kumar Mukherjee (Library Staff) Soumik Saha (Publications Secretary) Cover Design Anitesh Chakraborty Spedaf Thanks to : Do (Derozio Section) Souvik Gupta vaya Aviroop Sengupta, Bikram Kishore Bhattacharya, Cover Photographs Avishek Ghosal Ishita Kundu, Somiddho Basu, Samhita Sanyai Joy Saha • Illustration Sangbida Lahiri All rights of publications reserved by Presidency College, Kolkata. Printers : Jayasree Press, 91/IB, Baithakkhana Road, Kolkata~9 Published in 2009 by the Magazine Committee, Presidency College, Kolkata • (^enttettt^. Foreword Sanjib Ghosh 5 fiTtl ^tf^simi 42 7 Ctf^wrf^ 'STQ^ 43 ^hTRTST fw 8 io CT Cofft 43 9 Ttm^ 44 ®Flwt W 12 CWTf^itw CTtf^ Tf^ 44 twi'^irtn 44 17 TIME Lumbini Shill 45 Poulomi Ghosh 45 NAMELESS ME 20 Yashodhara Ghosh 46 SPRING-SONG : A BALLAD 22 Amrita Mukherjee -

T-Ara Black Eyes Album Download T-Ara - Cry Cry (Ballad Version) MP3

t-ara black eyes album download T-Ara - Cry Cry (Ballad Version) MP3. Download lagu T-Ara - Cry Cry (Ballad Version) MP3 dapat kamu download secara gratis di ilKPOP.net. Details lagu T-Ara - Cry Cry (Ballad Version) bisa kamu lihat di tabel, untuk link download T-Ara - Cry Cry (Ballad Version) berada dibawah. Title Cry Cry (Ballad Version) Artist T-Ara Album Black Eyes Genre Pop Year 2011 Duration 3:18 File Format mp3 Mime Type audio/mpeg Bitrate 128 kbps Size 3.06 MB Views 4,341x Uploaded on October, 08 2018 (09:05) Bila kamu mengunduh lagu T-Ara - Cry Cry (Ballad Version) MP3 usahakan hanya untuk review saja, jika memang kamu suka dengan lagu T- Ara - Cry Cry (Ballad Version) belilah kaset asli yang resmi atau CD official dari album Black Eyes, kamu juga bisa mendownload secara legal di Official iTunes T-Ara, untuk mendukung T-Ara - Cry Cry (Ballad Version) di semua charts dan tangga lagu Indonesia. KPOP DOWNLOAD. T-ara (티아라) - Black Eyes T-ara brought us back in time earlier in the year with their feel-good retro hit Roly Poly. Now they’re the picture of edgy, urban chic in their new mini-album Black Eyes. Their dramatic mid-tempo number Cry Cry has attracted a lot of attention for its movie-like music video in which Ji Yeon stars alongside Cha Seung Won and Ji Chang Wook. The mini-album includes the ballad version of Cry Cry and the new songs Goodbye, OK, O My God, and I’m So Bad. -

Menyebut) Nama Tuhanmu Your Lord Who Yang Menciptakan, Created 2

5 Appendix 1 Translation of Surah Al-Alaq verse 1-5 as follows: Page Chapter Indonesian English 1 1 1. Bacalah dengan 1. Recite in the name of (menyebut) nama Tuhanmu your Lord who yang Menciptakan, created 2. Dia Telah menciptakan 2. Created man from a manusia dari segumpal clinging substance darah. 3. Recite, and your Lord 3. Bacalah, dan is the most Generous Tuhanmulah yang Maha 4. Who taught by the pemurah, pen 4. Yang mengajar 5. Taught man that (manusia) dengan which he knew not. perantaran kalam 5. Dia mengajar kepada manusia apa yang tidak diketahuinya. 6 Appendix 2 The Five Fictions Written by Five Non-native Speakers What yours, is yours by Ismilenotfrown (Singapore) "Okay, we will be practicing till here! That's all for today!" Vixx's dance teacher clapped his hands while the members of vixx all fell onto the floor in relief. They can finally take a break after 10 hours of practice. Ken was the first one who get up and it was because he saw how tired Leo looked with all his sweat trickling down. He rushed towards the bench and took a bottle before rushing to Leo's side and passing it to Leo. "Taekwoon hyung, drink some water! You will feel more refresh!" Ken beamed and smiled to Leo. Just like always, Ken will always be there to cater to Leo. "Thank you Jaehwan." Leo nodded and took over the drink, without even turning to look at Ken . "Hyung, should we go out for dinner later? We can sneak out-" "I can't. -

What's That Noise?: Musical Boundaries and the Construction of Listening and Meaning

WHAT'S THAT NOISE?: MUSICAL BOUNDARIES AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF LISTENING AND MEANING Ian Davyd Gallimore Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Music Submitted January 2009 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Foremost, I would like to give thanks to my supervisor, Luke Windsor, for his enthusiasm and knowledge, for our sometimes mammoth but always enjoyable meetings, and for trusting that I knew what I was talking about when I wasn't really convinced of it myself. I am also grateful to Mic Spencer, for his remarks on an early draft of Chapter 2, and Kevin Dawe, for his helpful commentary during the formative stages of the thesis. I am indebted to my Master's supervisor, Fred Orton, for making me think harder and longer, not just about artworks but about everything, and without whose insight and vigour I might never have been able to start this thesis, never mind finish it. I would like to acknowledge the University of Reading Department of Psychology, for providing me with a workspace away from the distractions of home, sunny weather, and Wikipedia. I am especially thankful to the staff and post-grads who, during our daily lunchtime gatherings, provided much-needed relief from the stresses of writing up. -

|J[ Cove Jrsu »Pula

1 ' "i ; ■ ~ ~ I d a nS a g e d1 p a g | e a r , N o . 2 6 8 7 6 t h y e a r Twin Falls,5, Idaho IFriday, Septemiber l 25,1981 ________________ R e < a g a r 1 u n < c o v ej r s u m p o »pulai r c u its WASHINGTON (UPlU Pl)-President to keep;p a Hd on next year’s deficit,Icit, takes effect Oct.l and J d ste e r e d c le a r of re s tra inInt. t, He said the national debideb leads to an America ai work, to fiscal "But let there be no mistake: we hursday nighl his now pretre d lc tc d to rc a c h e d $43.1 billion, ----- Reagan-OUllInedJThur ion. a proposal that Socialal Security cost- will soonon rcoch $l trillion and the costcos sanlly, lo lower taxes2S and less Infla- have no0 choicect but to continue down , latest plan to baianccnee tho budget b y .. Reagaignn proposed cuts In defense;nse-'-of'llving boosts be dc delayed to save of inter[eresl p a y m e n ts a lo n e nowno\ tion," he said. “I bellelleve our plan for the roadid lowardlo a balanced budget - ; sp e n d inIng. g but onfy aboul 1 percentIt olof m oney. 1984.' a m o u nIt i tot< m ore th a n $96 billon, recovery Is sound andjit i will work. a budgel;cl lhalI will keep us strong at ‘ A 12 p e rc e n t spcndiriding cut for most the totalit'al b u d g e l - $3 billion in 1982 S ittin g b e h in d his b broad desk, his "Washiishlngton spends m ore on intcinter- The television appeae a l to th e p eople h o m e nnmd d s e c u re o v e rs e a s ," -------fcaeral-programs._aJ.a-tax.crackdown. -

Arianas ~Riet.R,:;~ / Micronesia's Leading Newspaper Since 19N ~ Fws

~--------------------------------·--------- 1, • ~ I '\ " ' ' ' ' I ' ' \ '"'. ' ... "' . ~ ',. ·-··_._._. I ·- ' \. '· I '} • I .. UNlVERSlTY OF HAWAII LIBRARY ---- - .. I Ii arianas ~riet.r,:;~ / Micronesia's Leading Newspaper Since 19n ~ fWS :_. ~- .: ; ·1 ·' :' FtJ Fr1~ f? ~-- {\:i ~-~ L;.{]-(i·Lf,/; ~';:~·1 ~.:. ,' ippines; . .. _ . "The union. has "requested . recognition but the employer said he couldn't make a deci sion until)an 15{.Mott said.. - Robert O'Connor, iawye~ .• for S~o Corp'.;saicl ·~the woi:1(-'.'. -ers 90n) ne~cf;the µhit:>h.'' •.. ·· ·. · KEEPING FINGERS CROSSED. Members of the Emergency Management Office's search and rescue team man a communications outpost at the Smiling Cove Marina awaiting word from other team members about four Tinian men reportedly missing at sea since Sunday. Photo by JoJo oAss Tenorio hits Underwood By Jojo Dass Governor insists 'CNMI delegate issue' Variety News Staff should not be Guam delegate's concern HOPE on the fate of the four persons who were reported miss that would give the CNMI a non something on this issue. ing at sea offTinian dimmed after voting delegate to the U.S. House "He started it." divers retrieved a t-shirt and a of Representatives, which, ac Tenorio, a former CNMI resi slipper believed to have belonged cording to Tenorio, is "not dent representative to Washing to one of the group as search and needed" by the CNMI. ton, D.C., said that the Guam del rescue entered its third day yes He added, however, that he egate should stick to legislation terday. would himself ask Congress to as it affects Guam. The search, said Emergency give the CNMI a delegate if at "In contrast to a full member of Management Office PIO Rose least 50 percent of all eligible the U.S. -

INDEX to YOLUME VIII, 18Ff

E. INDEX TO YOLUME VIII, 18Ff PAGE. A RUSDRED YEWTS (663 YILES) RACE-Lirutenant H.T.ALLEL.' mnd Cavalry... 61 CONVERS.4TlOSP ON CAVALRY.-BY Prince YRAITZU HOllEXU3HE-lLo .WIXGGY. TIUUs- lacod by Lieutenant CARL REIcHmAxx. ELEVrSTn Corvre~~on.-Ofthe Training Proper of the Remor Ita ............. 2p TWI~~~THCosvximArtats.-of the Traiuing of the Recruiu-. .... .................. 118 TetlrrrsXTnCoLveasATIoN.-The Subepueot Tralning of the Dlder Men and Hones.. .................... .............. 1P2 TUIRTW'TH CosveasmoN.-( ............. 'LLPI CESERAL HESRY LEAVEYWORTH.--Yajor GC~BGSB. DAVIS.. ............ '261 HlGE EXPIAXIVES AND INTRESCEISOTOOLS IN THEIR RELATIO! 3 TO CAVALRY. -Captnln WtLLILy D. BSACll. ............................... .................. 8 LIFE AND SERVICES OF GESERAL PHILIP ST. GEORGE CO0EE.C.: . ABYY.--Mnjor- : Geaerrl W~LSYM-. ............................ ................. 59 MAJOR-GESERAL JOHS BUFOFLD.-Y*Jor-GeneraI JAMB H. WIKUIL, I S.V.. .......... I7l bllLlTARY HEADlSG; ITS US€ AND ABCJE.-Lleutenant MARHEW ~.STKDLL..... OII PAVICIJLAR DISEASE-Lirotenant A. M. DAVIS.................. ............... 17 PROPPsslOSAL NOTES- Amerldn €In- lor French hmouuu...... ................. 268 A Record of the Experience with the Field Sketching Came at le Infantry md Cardry Gchooi .............................................. ............... 814 Austrian Cavalry.. ........................... .............88 Calvary Equipment.. ........ ..... ........... m *Cuiter's last Plght 'I.. .. ........................ ... ..- 69 Emex Troop's -

2005-09-08.Pdf

Wood-Ridqe • Caristadt • East Rutherford • Rutherford • Lyndhurst • North Arlington 9 ■ • ---------- ——;---- -— i Thursday, S ep te m b e r Established Ì 894 COMMUNITY BRIEFS down to be self-sufficient as a Fucci departm ent, as a city," said NIOR R e p o r t e r Russo, no stranger to flooding after wading across Route 17 UTHERFORD — “T h e LPL collecting for on Aug. 14 to rescue three they’ll be facing w ill be motorists trapped in their cars. hurricane victims erable,” said Police Russo added that as waters LYNDHURST — The lief Steven Nienstedt on the recede, the officers will be Lyndhurst Public Library is oyment of Sergeant John dealing largely with security collecting donations for the sso and Officer .Alford issues. American Red Cross erson III to New Orleans “Being police officers, H urricane 2005 R e lie f for the >t. 7. “But these are two of we’re trained in a full range of victims of Hurricane Katrina. inest.” problems with looters,” he Collection containers are ienstedt and Mayor located at every desk on all dette McPherson select- said. ‘This is one of the things we three floors of the library. the officers the morning of signed up for, the opportunity Call Donna Romeo at 201- >t. 6 from a long list of to help,” added Anderson, 804-2486 for more informa- >artment volunteers. who is on the Youth Advisory \ey thanked their families Council and is a School »porting them undertak- Resource Officer in le mission. NA w ill remember Rutherford. le two will be deployed to The officers will be tragedy of 9/11 le 2nd District of New deployed for 14 days, plus an N O R TH ARLINGTON — ns, setting up an emer additional two days travel To remember the tragedy of gency command precinct with time, at the end of which they Photo by Jeft Fucci Sept. -

ODHAM & TUDOR Inc

I Mr. and Mrs. YOU You are looking for the best home you can buy with the money you have to work with. CONSIDER WISELY « The purchase of a home will possibly be the biggest, most important investment you will make in your lifetime i Make A Windshield Appraisal . of Pinecrest, South Pinecrest and South Pinecrest Second Addition TODAY. Knock on any door of home owners In these lovely Odham & Tudor developments. They are happy home owners, and they will be glad to give you all the reasons in the world why you should live in South Pinecrest Second Addition. • SOUTH PINECREST second addition Is located in one of San • We can qualify you for one of our finance plans In 30 minutes. ford’s nicest locations. Luxury homes at moderate prices, city Act now and you can choose your paint colors inside and out on any water, city sewers, paved streets, intelligent zoning and complete home under construction. new Florida styling. • FHA IN SERVICE down payment and closing cost as low as • OUR AIM is to build for you the buyer the very best home we $1,300. Monthly payments cheaper than rent can at a price you can afford. • OUR POLICY Is to guarantee the workmanship and material used • FHA Down payment and closing cost as low as 1,500. Monthly in the homes we build for a period of one year. You must be sat payments cheaper than rent isfied or we will return your money. Priced From $13,500 to $18,000 11 We Have A Home For You" ODHAM & TUDOR Inc.