Fighting Jim Crow in Post-World War II Omaha 1945-1956

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

African American Resources at History Nebraska

AFRICAN AMERICAN RESOURCES AT HISTORY NEBRASKA History Nebraska 1500 R Street Lincoln, NE 68510 Tel: (402) 471-4751 Fax: (402) 471-8922 Internet: https://history.nebraska.gov/ E-mail: [email protected] ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS RG5440: ADAMS-DOUGLASS-VANDERZEE-MCWILLIAMS FAMILIES. Papers relating to Alice Cox Adams, former slave and adopted sister of Frederick Douglass, and to her descendants: the Adams, McWilliams and related families. Includes correspondence between Alice Adams and Frederick Douglass [copies only]; Alice's autobiographical writings; family correspondence and photographs, reminiscences, genealogies, general family history materials, and clippings. The collection also contains a significant collection of the writings of Ruth Elizabeth Vanderzee McWilliams, and Vanderzee family materials. That the Vanderzees were talented and artistic people is well demonstrated by the collected prose, poetry, music, and artwork of various family members. RG2301: AFRICAN AMERICANS. A collection of miscellaneous photographs of and relating to African Americans in Nebraska. [photographs only] RG4250: AMARANTHUS GRAND CHAPTER OF NEBRASKA EASTERN STAR (OMAHA, NEB.). The Order of the Eastern Star (OES) is the women's auxiliary of the Order of Ancient Free and Accepted Masons. Founded on Oct. 15, 1921, the Amaranthus Grand Chapter is affiliated particularly with Prince Hall Masonry, the African American arm of Freemasonry, and has judicial, legislative and executive power over subordinate chapters in Omaha, Lincoln, Hastings, Grand Island, Alliance and South Sioux City. The collection consists of both Grand Chapter records and subordinate chapter records. The Grand Chapter materials include correspondence, financial records, minutes, annual addresses, organizational histories, constitutions and bylaws, and transcripts of oral history interviews with five Chapter members. -

The Omaha Gospel Complex in Historical Perspective

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for Summer 2000 The Omaha Gospel Complex In Historical Perspective Tom Jack College of Saint Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Jack, Tom, "The Omaha Gospel Complex In Historical Perspective" (2000). Great Plains Quarterly. 2155. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/2155 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THE OMAHA GOSPEL COMPLEX IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE TOM]ACK In this article, I document the introduction the music's practitioners, an examination of and development of gospel music within the this genre at the local level will shed insight African-American Christian community of into the development and dissemination of Omaha, Nebraska. The 116 predominantly gospel music on the broader national scale. black congregations in Omaha represent Following an introduction to the gospel twenty-five percent of the churches in a city genre, the character of sacred music in where African-Americans comprise thirteen Omaha's African-American Christian insti percent of the overall population.l Within tutions prior to the appearance of gospel will these institutions the gospel music genre has be examined. Next, the city's male quartet been and continues to be a dynamic reflection practice will be considered. Factors that fa of African-American spiritual values and aes cilitated the adoption of gospel by "main thetic sensibilities. -

Omaha, Nebraska, Experienced Urban Uprisings the Safeway and Skaggs in 1966, 1968, and 1969

Nebraska National Guardsmen confront protestors at 24th and Maple Streets in Omaha, July 5, 1966. NSHS RG2467-23 82 • NEBRASKA history THEN THE BURNINGS BEGAN Omaha’s Urban Revolts and the Meaning of Political Violence BY ASHLEY M. HOWARD S UMMER 2017 • 83 “ The Negro in the Midwest feels injustice and discrimination no 1 less painfully because he is a thousand miles from Harlem.” DAVID L. LAWRENCE Introduction National in scope, the commission’s findings n August 2014 many Americans were alarmed offered a groundbreaking mea culpa—albeit one by scenes of fire and destruction following the that reiterated what many black citizens already Ideath of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. knew: despite progressive federal initiatives and Despite the prevalence of violence in American local agitation, long-standing injustices remained history, the protest in this Midwestern suburb numerous and present in every black community. took many by surprise. Several factors had rocked In the aftermath of the Ferguson uprisings, news Americans into a naïve slumber, including the outlets, researchers, and the Justice Department election of the country’s first black president, a arrived at a similar conclusion: Our nation has seemingly genial “don’t-rock-the-boat” Midwestern continued to move towards “two societies, one attitude, and a deep belief that racism was long black, one white—separate and unequal.”3 over. The Ferguson uprising shook many citizens, To understand the complexity of urban white and black, wide awake. uprisings, both then and now, careful attention Nearly fifty years prior, while the streets of must be paid to local incidents and their root Detroit’s black enclave still glowed red from five causes. -

The Origins and Operations of the Kansas City Livestock

REGULATION IN THE LIVESTOCK TRADE: THE ORIGINS AND OPERATIONS OF THE KANSAS CITY LIVESTOCK EXCHANGE 1886-1921 By 0. JAMES HAZLETT II Bachelor of Arts Kansas State University Manhattan, Kansas 1969 Master of Arts Oklahoma State University stillwater, Oklahoma 1982 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May, 1987 The.s; .s I q 8111 0 H~3\,.. ccy;, ;i. REGULATION IN THE LIVESTOCK TRADE: THE ORIGINS AND OPERATIONS OF THE KANSAS CITY LIVESTOCK EXCHANGE 1886-1921 Thesis Approved: Dean of the Graduate College ii 1286885 C Y R0 I GP H T by o. James Hazlett May, 1987 PREFACE This dissertation is a business history of the Kansas City Live Stock Exchange, and a study of regulation in the American West. Historians generally understand the economic growth of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and the business institutions created during that era, within the perspective of "progressive" history. According to that view, Americans shifted from a public policy of laissez faire economics to one of state regulation around the turn of the century. More recently, historians have questioned the nature of regulation in American society, and this study extends that discussion into the livestock industry of the American West. 1 This dissertation relied heavily upon the minutes of the Kansas City Live Stock Exchange. Other sources were also important, especially the minutes of the Chicago Live Stock Exchange, which made possible a comparison of the two exchanges. Critical to understanding the role of the Exchange but unavailable in Kansas City, financial data was 1Morton Keller, "The Pluralist State: American Economic Regulation in Comparative Perspective, 1900-1930," in Thomas K. -

Fort Worth Stockyards Historic District 06/29/1976

Form No 10-300 (Rev 10-741 PH01011133 DATA SHEETc>^^^ ^//^^^ UNITED STATES DEP.XRTMENT OE THE INTERIOR FOR NPS USE ONLY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE ftOD 2 9 1975 RECEIVED APR " ' NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY NOMINATION FORM DATE ENTERED J\iH Z 9 ^^^^ SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS QNAME -JI^I^ISTORIC Fort Worth Stockyards Historic District AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET81 NUMBER -NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Fort Worth VICINITY OF 12 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Texas 048 Tarrant 439 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENTUSE ^DISTRICT -PUBLIC ^OCCUPIED ^L^GRICULTURE —MUSEUM X BUILDING(S) •.PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED -COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE -BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE X ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED -GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC X -BEING CONSIDERED _YES: UNRESTRICTED INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _N0 MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Multiple ownership STREETS. NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC Tarrant Cotinty Courthouse STREET& NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Fort Worth Texas a REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic Sites Inventory & Recorded Texas Historic Landmark DATE 1975 & 1967 .FEDERAL ^STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS joxas Historlcal Commission CITY. TOWN STATE Austin Texas DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED UNALTERED X_ORIGINALSITE X GOOD —RUINS 5C_ALTERED -MOVED DATE- -FAIR —UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Fort Worth is located in north central Texas near the headwaters of the Trinity River. The famous Chisolm Trail crossed the Trinity River at a point near Fort Worth and the impetus of the cattle drives from south and central Texas through Fort Worth spurred the growth of that early settlement. -

Swollenjbiands 8 100-Foot Low Riveted Trusses, 20-Foot and "O" Sts

r, RENT. IIEA1. ESTATE—FOK KAI.E. COUNTY OFFICIAL NOTICES. LEGAL NOTICES. ANNOI M KMKNTft FINANriAU | REAL ESTATE—FOR *1 Holism—North ••• BRITISH ADMIRAL thereof, and all objections thereto or 9th District, Sokol Hall. 1245 So. 13th Personal*. I Ileal K*tate loan*. 14 Apartments—I nlurnislied. claims for damages must be filed in the St. RALE—A new all modern Lrtwm C’lerk's office on or noon 9th District. Vinton School. 21st and Industrial home MONEY TO Loan FnR County before THE SALVATION ARMY 1.»» imor« Ave. »4 1»0. Deer Park Blvd. On first and second mortgage*. LOOK AT THESE VALUES. bungalow 44311 BURIED AT SEA of the lOtft day of December. A. D., 1924, solicit* your old clothing furnltura. mags 4904 10th Comenlus School. 16th We outright for cash 3 rooms 1240 S 15th SI.I * 00 1360 down KK. , or said road will be opened without ref- District, zlnes. We collect We distribute. Phone buy 3 225 Cedar H»9IW. Portsmouth, England, Oct. 23.— erence thereto. and William Sts. JA. 413& and our wagon will call. Call Existing mortgages and land contracts. rooms. St.!'?■£“ II J.' Itf'I’K ^ <*« » *»UV and »>H 11th and 5 rooms. 1201 Pacific St FRANK DEWEY. 11th District. Lincoln School. and our new home. 2<>9 N 13th St Prompt Action. .}1M0 Without ceremonial of any kind, the Inspect Grace St. part modern. I 0-2 N-8 County Clerk. Center Sts. H. A. WOLFE CO., 5 rooms. 2018 4R34 n 40TH 8T—elx-room 12th District, Bt. Joseph School, 16th “1 2 3 2 6 7 !» •582 Saunders Kennedy 3160 5 rooms, flat. -

A North 24Th Street Case Study Tiffany Hunter [email protected]

University of Nebraska at Omaha Masthead Logo DigitalCommons@UNO Theses/Capstones/Creative Projects University Honors Program 5-2019 Revitalizing the Street of Dreams: A North 24th Street Case Study Tiffany Hunter [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/ university_honors_program Part of the Finance and Financial Management Commons, Real Estate Commons, and the Taxation Commons Recommended Citation Hunter, Tiffany, "Revitalizing the Street of Dreams: A North 24th Street Case Study" (2019). Theses/Capstones/Creative Projects. 41. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/university_honors_program/41 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Footer Logo University Honors Program at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses/Capstones/Creative Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REVITALIZING THE STREET OF DREAMS: A NORTH 24TH STREET CASE STUDY University Honors Program Thesis University of Nebraska at Omaha Submitted by Tiffany Hunter May 2019 Advisor: David Beberwyk ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to analyze the North 24th Street corridor in Omaha, Nebraska, to highlight the benefits of investing in commercial real estate development, propose tools for financing new development or redevelopment projects, and to suggest methods of building a coherent development plan to avoid gentrification. Commercial development provides the following: quality business space, accessible jobs for an underemployed populace, additional tax revenue, and a reduction in community detriments such as crime, empty lots, and low property values. The North 24th Street corridor has economic potential, as it is less than one mile from downtown Omaha, the core of the city. -

UG Scholarships.Pdf

CREIGHTON UNIVERSITY Undergraduate Scholarship Descriptions as of June 2012 Fund Title Bulletin Description Ahmanson Foundation Scholarships Each year scholarships are awarded from funds provided annually by the Ahmanson Foundation. Recipients must demonstrate financial need through the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) and be above average scholastically. A 3.0 GPA average must be maintained for renewal. Victor and Mary Albertazzi Scholarship This award recognizes an academically talented undergraduate student who is in need of assistance to begin or continue their education at Creighton. The Financial Aid Office will select new recipients annually as well as confirm renewal of previous awards based on academic credentials and financial need. A 2.5 cum QPA and normal grade level progression are required for renewal. Alpha Sigma Nu Scholarship This scholarship is funded by annual gifts from Alpha Sigma Nu, the National Jesuit Honor Society. The annual scholarship is available to an undergraduate student based on financial need and scholastic achievement. Alumni Association Scholarships These competitive renewable annual awards are offered to children of Creighton alumni and are based on academic achievement. A 2.8 GPA is required for renewal. AMDG RAD Scholarship This endowed scholarship was established in 1998 by Dr. and Mrs. Kenneth Conry. It is awarded to a financially needy student enrolled in the School of Nursing or the College of Arts and Sciences. Preference is given to a student majoring in chemistry. It is renewable by maintaining normal academic progress toward a degree. Harold and Marian Andersen Family Fund Scholarship This endowed scholarship was established in 1995 by Mr. -

Omaha Area Schools

High Schools near Zip Code 68102 School Grades Students P/T Ratio Zipcode Central High School 09-12 2592 17.7 68102 Burke High School 09-12 2092 17.5 68154 Omaha North Magnet High School 09-12 1924 17.3 68111 Bryan High School 09-12 1758 17.5 68157 Omaha South Magnet High School 09-12 1740 14.9 68107 Benson Magnet High School 09-12 1526 15.6 68104 Omaha Northwest High School 09-12 1416 15.5 68134 (* = alternative school) Middle Schools near Zip Code 68102 School Grades Students P/T Ratio Zipcode King Science/Tech Magnet Middle School 07-08 399 10.9 68110 Bryan Middle School 07-08 821 13.7 68147 Norris Middle School 07-08 758 13.9 68106 Beveridge Magnet Middle School 07-08 720 13.6 68144 Mc Millan Magnet Middle School 07-08 686 13.5 68112 Morton Magnet Middle School 07-08 633 13.7 68134 Alice Buffett Magnet Middle School 07-08 632 15.7 68164 Monroe Middle School 07-08 586 12.7 68104 Lewis & Clark Middle School 07-08 564 12.7 68132 R M Marrs Magnet Middle School 07-08 515 11.4 68107 Hale Middle School 07-08 290 9 68152 Elementary Schools near Zip Code 68102 School Grades Students P/T Ratio Zipcode Liberty Elementary School PK-06 591 11.7 68102 Kellom Elementary School PK-06 351 11 68102 Bancroft Elementary School PK-06 674 12.5 68108 Field Club Elementary School PK-06 643 14.8 68105 Jefferson Elementary School PK-06 516 16.5 68105 Castelar Elementary School PK-06 488 11.2 68108 Lothrop Magnet Center PK-06 366 12.7 68110 Walnut Hill Elementary School PK-06 345 12.5 68131 Conestoga Magnet Elementary School PK-06 305 10 68110 King Science/Tech -

Download This

i n <V NFS Form 10-900 OMB NO. 1024-0018 (Rev. 8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900a). Type all entries. 1. Name of Property_________________________________________________ historic name N/A other names/site number South Omaha Main Street Historic District 2. Location street & number 4723-5002 So. 24th Street N ffi^ not for publication city, town Omaha N /A! vicinity state Nebraska code NE county Douglas code Q55 zip code 68107 3. Classification Ownership of Property Category of Property Number of Resources within Property X private I I building(s) Contributing Noncontributing public-local fxl district buildings public-State EH site _ sites public-Federal I I structure _0_ structures I I object _0_ objects 36 _9_Total Name of related multiple property listing: Number of contributing resources previously N/A listed in the National Register 1 ___ 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this [x] nomination LJ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

On the Front Lines for Racial Equality

WWCREIGHTONINDOWINDOW UNIVERSITY ■ WINTER 1995-96 FatherFather Markoe:Markoe: Our ‘Champagne A Life Glass’ Economy on the Don’t Play TV Front Lines Trivia With Her for Racial Finding God in Equality Your Daily Life LETTERS WINDOW Magazine edits Letters to the INDOW Editor, primarily to conform to space W■ ■ limitations. Personally signed letters Volume 12/Number 2 Creighton University Winter 1995-96 are given preference for publication. Our FAX number is: (402) 280-2549. E-Mail to: [email protected] Fr. Markoe’s Battle Against Racism ‘And If the Rules Change?’ Bob Reilly tells you about a man who I have read with interest the article “The was a lifelong fighter. Fr. Markoe Social Roots of Our Environmental found a cause for his fighting ener- Predicament” by Dr. Harper in your Fall gy. The word portrait of a strong- 1995 issue of WINDOW. minded Jesuit begins on Page 3. I would like to pose a question for Dr. Harper. In this third human environmental The Rich Get Richer, revolution, supposing we were to discov- er an inexhaustible source of energy. I The Poor Get Poorer am assuming that the laws of supply and Gerard Stockhausen, S.J., talks about what he calls “our cham- demand would eventually lead it to be at pagne-glass economy.” In this case, it doesn’t mean champagne an inconsequential cost. for everyone; it means the shape of our economy that puts the What would that do to the human liv- rich at the broad top of the glass and the poor at the narrow ing conditions in the world? bottom. -

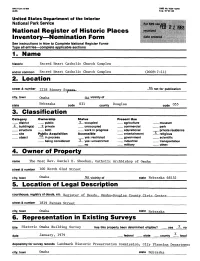

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form 1

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-OO18 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name historic Sacred Heart Catholic Church Complex and/or common Sacred Heart Catholic Church Complex (D009.:7-Il) 2. Location street & number 2 218 Binnev city, town Omaha vicinity of state Nebraska code 031 county Douglas code 055 3. Classification Cat.egory Ownership Status Present Use district public X occupied agriculture museum X building(s) _ X. private unoccuoied __ commercial park structure both work in oroaress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment x religious NA object 1NA in process ves: restricted government scientific being considered X yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military nther- 4. Owner off Property name The Most Rev. Daniel E. Sheehan, Catholic Archbishop of Omaha street & number 100 North 62nd Street city, town Omaha state Nebraska 68132 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Register of Deeds. Omaha-Douglas County CiviV C. street & number 1819 Farnam Street city, town state Nebraska 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title Historic Omaha Building Survey has this property been determined eligible? yes X no X date . federal state county local depository for survey records Landmark Historic Preservation Commission, City Planning Department city, town Omaha state Nebraska 7. Description Condition Check one Check one __ deteriorated X unaltered X original site ruins altered moved date NA fair unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance The tall spire (124 feet) and rock-faced ashlar walls of the Sacred Heart Catholic Church are dominant features in the flat, late 19th-and-20th-century residential neighborhood of Kountze Place, where two-and-one-half-story frame houses are the norm.