Pepsi-Cola Building Designation Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

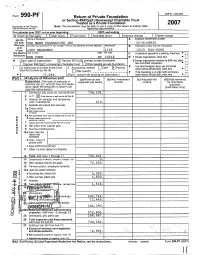

Return of Private Foundation

OMB No 1545.0052 Form 990 P F Return of Private Foundation or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation 2007 Department of the Treasury Note : The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state Internal Revenue Service For calendar year 2007, or tax year be ginnin g , 2007 , and endin g I G Check all that apply Initial return Final return Amended return Address change Name change Name of foundation A Employer identification number Use the IRS label THE MANN FOUNDATION INC 32-0149835 Otherwise , Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number (see the instructions) print or type 1385 BROADWAY 1 1102 (212) 840-6266 See Specific City or town State ZIP code C If exemption application is pending, check here Instructions. ► NEW YORK NY 1 0 0 1 8 D 1 Foreign organizations , check here ► H Check type of organization Section 501 (c)(3exempt private foundation 2 Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, check q here and attach computation Section 4947(a ) (1) nonexem p t charitable trust Other taxable p rivate foundation ► foundation status was terminated Accrual E If private ► Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method Cash X under section 507(b)(1 XA), check here (from Part ll, column (c), line 16) Other (s pecify) _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination (d) on cash basis) under section 507(b)(1)(B), check here ► $ -2,064. -

RITZ TOWER, 465 Park Avenue (Aka 461-465 Park Avenue, and 101East5t11 Street), Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission October 29, 2002, Designation List 340 LP-2118 RITZ TOWER, 465 Park Avenue (aka 461-465 Park Avenue, and 101East5T11 Street), Manhattan. Built 1925-27; Emery Roth, architect, with Thomas Hastings. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1312, Lot 70. On July 16, 2002 the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Ritz Tower, and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No.2). The hearing had been advertised in accordance with provisions of law. Ross Moscowitz, representing the owners of the cooperative spoke in opposition to designation. At the time of designation, he took no position. Mark Levine, from the Jamestown Group, representing the owners of the commercial space, took no position on designation at the public hearing. Bill Higgins represented these owners at the time of designation and spoke in favor. Three witnesses testified in favor of designation, including representatives of State Senator Liz Kruger, the Landmarks Conservancy and the Historic Districts Council. In addition, the Commission has received letters in support of designation from Congresswoman Carolyn Maloney, from Community Board Five, and from architectural hi storian, John Kriskiewicz. There was also one letter from a building resident opposed to designation. Summary The Ritz Tower Apartment Hotel was constructed in 1925 at the premier crossroads of New York's Upper East Side, the comer of 57t11 Street and Park A venue, where the exclusive shops and artistic enterprises of 57t11 Street met apartment buildings of ever-increasing height and luxury on Park Avenue. -

Seagram Building, First Floor Interior

I.andmarks Preservation Commission october 3, 1989; Designation List 221 IP-1665 SEAGRAM BUIIDING, FIRST FLOOR INTERIOR consisting of the lobby and passenger elevator cabs and the fixtures and interior components of these spaces including but not limited to, interior piers, wall surfaces, ceiling surfaces, floor surfaces, doors, railings, elevator doors, elevator indicators, and signs; 375 Park Avenue, Manhattan. Designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe with Philip Johnson; Kahn & Jacobs, associate architects. Built 1956-58. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1307, Lot 1. On May 17, 1988, the landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Seagram Building, first floor interior, consisting of the lobby and passenger elevator cabs and the fixtures and interior components of these spaces including but not limited to, interior piers, wall surfaces, ceiling surfaces, floor surfaces, doors, railings, elevator doors, elevator indicators, and signs; and the proposed designation of the related I.and.mark Site (Item No. 2). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Twenty witnesses, including a representative of the building's owner, spoke in favor of designation. No witnesses spoke in opposition to designation. The Commission has received many letters in favor of designation. DFSCRIPI'ION AND ANALYSIS Summary The Seagram Building, erected in 1956-58, is the only building in New York City designed by architectural master Iudwig Mies van der Rohe. Constructed on Park Avenue at a time when it was changing from an exclusive residential thoroughfare to a prestigious business address, the Seagram Building embodies the quest of a successful corporation to establish further its public image through architectural patronage. -

General Info.Indd

General Information • Landmarks Beyond the obvious crowd-pleasers, New York City landmarks Guggenheim (Map 17) is one of New York’s most unique are super-subjective. One person’s favorite cobblestoned and distinctive buildings (apparently there’s some art alley is some developer’s idea of prime real estate. Bits of old inside, too). The Cathedral of St. John the Divine (Map New York disappear to differing amounts of fanfare and 18) has a very medieval vibe and is the world’s largest make room for whatever it is we’ll be romanticizing in the unfinished cathedral—a much cooler destination than the future. Ain’t that the circle of life? The landmarks discussed eternally crowded St. Patrick’s Cathedral (Map 12). are highly idiosyncratic choices, and this list is by no means complete or even logical, but we’ve included an array of places, from world famous to little known, all worth visiting. Great Public Buildings Once upon a time, the city felt that public buildings should inspire civic pride through great architecture. Coolest Skyscrapers Head downtown to view City Hall (Map 3) (1812), Most visitors to New York go to the top of the Empire State Tweed Courthouse (Map 3) (1881), Jefferson Market Building (Map 9), but it’s far more familiar to New Yorkers Courthouse (Map 5) (1877—now a library), the Municipal from afar—as a directional guide, or as a tip-off to obscure Building (Map 3) (1914), and a host of other court- holidays (orange & white means it’s time to celebrate houses built in the early 20th century. -

Assessment Actions

Assessment Actions Borough Code Block Number Lot Number Tax Year Remission Code 1 1883 57 2018 1 385 56 2018 2 2690 1001 2017 3 1156 62 2018 4 72614 11 2018 2 5560 1 2018 4 1342 9 2017 1 1390 56 2018 2 5643 188 2018 1 386 36 2018 1 787 65 2018 4 9578 3 2018 4 3829 44 2018 3 3495 40 2018 1 2122 100 2018 3 1383 64 2017 2 2938 14 2018 Page 1 of 604 09/27/2021 Assessment Actions Owner Name Property Address Granted Reduction Amount Tax Class Code THE TRUSTEES OF 540 WEST 112 STREET 105850 2 COLUM 226-8 EAST 2ND STREET 228 EAST 2 STREET 240500 2 PROSPECT TRIANGLE 890 PROSPECT AVENUE 76750 4 COM CRESPA, LLC 597 PROSPECT PLACE 23500 2 CELLCO PARTNERSHIP 6935500 4 d/ CIMINELLO PROPERTY 775 BRUSH AVENUE 329300 4 AS 4305 65 REALTY LLC 43-05 65 STREET 118900 2 PHOENIX MADISON 962 MADISON AVENUE 584850 4 AVENU CELILY C. SWETT 277 FORDHAM PLACE 3132 1 300 EAST 4TH STREET H 300 EAST 4 STREET 316200 2 242 WEST 38TH STREET 242 WEST 38 STREET 483950 4 124-469 LIBERTY LLC 124-04 LIBERTY AVENUE 70850 4 JOHN GAUDINO 79-27 MYRTLE AVENUE 35100 4 PITKIN BLUE LLC 1575 PITKIN AVENUE 49200 4 GVS PROPERTIES LLC 559 WEST 164 STREET 233748 2 EP78 LLC 1231 LINCOLN PLACE 24500 2 CROTONA PARK 1432 CROTONA PARK EAS 68500 2 Page 2 of 604 09/27/2021 Assessment Actions 1 1231 59 2018 3 7435 38 2018 3 1034 39 2018 3 7947 17 2018 4 370 1 2018 4 397 7 2017 1 389 22 2018 4 3239 1001 2018 3 140 1103 2018 3 1412 50 2017 1 1543 1001 2018 4 659 79 2018 1 822 1301 2018 1 2091 22 2018 3 7949 223 2018 1 471 25 2018 3 1429 17 2018 Page 3 of 604 09/27/2021 Assessment Actions DEVELOPM 268 WEST 84TH STREET 268 WEST 84 STREET 85350 2 BANK OF AMERICA 1415 AVENUE Z 291950 4 4710 REALTY CORP. -

Leseprobe 9783791384900.Pdf

NYC Walks — Guide to New Architecture JOHN HILL PHOTOGRAPHY BY PAVEL BENDOV Prestel Munich — London — New York BRONX 7 Columbia University and Barnard College 6 Columbus Circle QUEENS to Lincoln Center 5 57th Street, 10 River to River East River MANHATTAN by Ferry 3 High Line and Its Environs 4 Bowery Changing 2 West Side Living 8 Brooklyn 9 1 Bridge Park Car-free G Train Tour Lower Manhattan of Brooklyn BROOKLYN Contents 16 Introduction 21 1. Car-free Lower Manhattan 49 2. West Side Living 69 3. High Line and Its Environs 91 4. Bowery Changing 109 5. 57th Street, River to River QUEENS 125 6. Columbus Circle to Lincoln Center 143 7. Columbia University and Barnard College 161 8. Brooklyn Bridge Park 177 9. G Train Tour of Brooklyn 195 10. East River by Ferry 211 20 More Places to See 217 Acknowledgments BROOKLYN 2 West Side Living 2.75 MILES / 4.4 KM This tour starts at the southwest corner of Leonard and Church Streets in Tribeca and ends in the West Village overlooking a remnant of the elevated railway that was transformed into the High Line. Early last century, industrial piers stretched up the Hudson River from the Battery to the Upper West Side. Most respectable New Yorkers shied away from the working waterfront and therefore lived toward the middle of the island. But in today’s postindustrial Manhattan, the West Side is a highly desirable—and expensive— place, home to residential developments catering to the well-to-do who want to live close to the waterfront and its now recreational piers. -

CITY of HOUSTON Archaeological & Historical Commission Planning and Development Department

CITY OF HOUSTON Archaeological & Historical Commission Planning and Development Department LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT LANDMARK NAME: Melrose Building AGENDA ITEM: C OWNERS: Wang Investments Networks, Inc. HPO FILE NO.: 15L305 APPLICANT: Anna Mod, SWCA DATE ACCEPTED: Mar-02-2015 LOCATION: 1121 Walker Street HAHC HEARING DATE: Mar-26-2015 SITE INFORMATION Tracts 1, 2, 3A & 16, Block 94, SSBB, City of Houston, Harris County, Texas. The site includes a 21- story skyscraper. TYPE OF APPROVAL REQUESTED: Landmark Designation HISTORY AND SIGNIFICANCE SUMMARY The Melrose Building is a twenty-one story office tower located at 1121 Walker Street in downtown Houston. It was designed by prolific Houston architecture firm Lloyd & Morgan in 1952. The building is Houston’s first International Style skyscraper and the first to incorporate cast concrete cantilevered sunshades shielding rows of grouped windows. The asymmetrical building is clad with buff colored brick and has a projecting, concrete sunshade that frames the window walls. The Melrose Building retains a high degree of integrity on the exterior, ground floor lobby and upper floor elevator lobbies. The Melrose Building meets Criteria 1, 4, 5, and 6 for Landmark designation of Section 33-224 of the Houston Historic Preservation Ordinance. HISTORY AND SIGNIFICANCE Location and Site The Melrose Building is located at 1121 Walker Street in downtown Houston. The property includes only the office tower located on the southeastern corner of Block 94. The block is bounded by Walker Street to the south, San Jacinto Street to the east, Rusk Street to the north, and Fannin Street to the west. The surrounding area is an urban commercial neighborhood with surface parking lots, skyscrapers, and multi-story parking garages typical of downtown Houston. -

Vornado Realty Trust

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM 8-K Current report filing Filing Date: 2017-06-05 | Period of Report: 2017-06-05 SEC Accession No. 0001104659-17-037358 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER VORNADO REALTY TRUST Mailing Address Business Address 888 SEVENTH AVE 888 SEVENTH AVE CIK:899689| IRS No.: 221657560 | State of Incorp.:MD | Fiscal Year End: 0317 NEW YORK NY 10019 NEW YORK NY 10019 Type: 8-K | Act: 34 | File No.: 001-11954 | Film No.: 17889956 212-894-7000 SIC: 6798 Real estate investment trusts VORNADO REALTY LP Mailing Address Business Address 888 SEVENTH AVE 210 ROUTE 4 EAST CIK:1040765| IRS No.: 133925979 | State of Incorp.:DE | Fiscal Year End: 1231 NEW YORK NY 10019 PARAMUS NJ 07652 Type: 8-K | Act: 34 | File No.: 001-34482 | Film No.: 17889957 212-894-7000 SIC: 6798 Real estate investment trusts Copyright © 2017 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, DC 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported): June 5, 2017 VORNADO REALTY TRUST (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in Charter) Maryland No. 001-11954 No. 22-1657560 (State or Other (Commission (IRS Employer Jurisdiction of File Number) Identification No.) Incorporation) VORNADO REALTY L.P. (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in Charter) Delaware No. 001-34482 No. 13-3925979 (State or Other (Commission (IRS Employer Jurisdiction of -

ORAL HISTORY of NATALIE DE BLOIS Interviewed by Betty J. Blum

ORAL HISTORY OF NATALIE DE BLOIS Interviewed by Betty J. Blum Compiled under the auspices of the Chicago Architects Oral History Project The Ernest R. Graham Study Center for Architectural Drawings Department of Architecture The Art Institute of Chicago Copyright © 2004 The Art Institute of Chicago This manuscript is hereby made available to the public for research purposes only. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publication, are reserved to the Ryerson and Burnham Libraries of The Art Institute of Chicago. No part of this manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of The Art Institute of Chicago. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface iv Outline of Topics vi Oral History 1 Selected References 143 Curriculum Vitae 146 Index of Names and Buildings 147 iii PREFACE It is not surprising, despite the fact that architecture was a male-dominated profession, that Natalie de Blois set her sights on becoming an architect early on. Surrounded by the talk and tools of the trade, she continues an unbroken chain of three generations of Griffin family achievements and interest in building. De Blois was headed for MIT but was diverted by the Depression to Columbia University, where she studied architecture. After graduation, de Blois began her fifty-year career in architecture in 1944 at the office of Skidmore Owings and Merrill, New York. It was in that office, under the wing of Gordon Bunshaft, that de Blois blossomed. She worked with Bunshaft on important and challenging projects and her pleasure in that she thought was reward enough. However, as one of the few women in architecture at that time, she suffered the slights and indifference to which women were often subjected. -

May 5, 2016 Game-Changing Real Estate Puts Rapaport in The

May 5, 2016 http://rew-online.com/2016/05/05/game-changing-real-estate-puts-rapaport-in-the-winners-circle/ Game-changing real estate puts Rapaport in the winners circle BY DAN ORLANDO Laura Rapaport, senior vice president at L&L Holding Company, will be taking part in the Real Estate Weekly Women’s Forum next week. Once in pursuit of a career in medicine, Rapaport’s path to her current role was not devoid of twists and turns. “When I was 18, I took an unpaid internship with Earle Altman at Helmsley Spear. After doing what seemed like two weeks of work in just one morning, I was told that if I got my license and closed a deal, they would pay me,” Rapaport recalled. “I got my license and managed to nail a lease on a small property in Queens. That’s when I got the real estate bug.” A University of Pennsylvania graduate, Rapaport said that entering the competitive field was made easier because of the excellent mentorships she has been the beneficiary of. At the forum, she hopes that she’ll be able to positively influence other young real estate professionals, male and female, in a similar manner. “I have been fortunate to work with and learn from some of the industry greats. First there was Earle, and then my mentor Tara Stacom. Each taught me and showed me how exciting and dynamic the real estate industry was and have helped to cultivate my knowledge and experience going forward.” While her past has certainly molded her, Rapaport’s current role has allowed her to truly blossom. -

Monthly Market Report

MAY 2017 Monthly Market Report SALES SUMMARY .......................... 2 HISTORICAL PERFORMANCE ....... 4 NEW DEVELOPMENTS ................... 2 5 NOTABLE NEW LISTINGS .............. 4 6 SNAPSHOT ...................................... 7 7 8 CityRealty is the website for NYC real estate, providing high-quality listings and tailored agent matching for pro- spective apartment buyers, as well as in-depth analysis of the New York real estate market. MONTHLY MARKET REPORT MAY 2017 Summary MOST EXPENSIVE SALES The average sales price and number of Manhattan apartment sales both increased in the four weeks leading up to April 1. The average price for an apartment—taking into account both condo and co-op sales—was $2.3 million, up from $2.2 million the prior month. The number of recorded sales, 817, was up from the 789 recorded in the preceding month. AVERAGE SALES PRICE CONDOS AND CO-OPS $65.1M 432 Park Avenue, #83 $2.3 Million 6+ Beds, 6+ Baths Approx. 8,055 ft2 ($8,090/ft2) The average price of a condo was $3.6 million and the average price of a co-op was $1.2 million. There were 389 condo sales and 428 co-op sales. RESIDENTIAL SALES 817 $1.9B UNITS GROSS SALES The top sale this month was in 432 Park Avenue. Unit 83 in the property sold for $65 million. The apartment, one of the largest in 432 Park, has six+ bedrooms, six+ bathrooms, and measures 8,055 square feet. $43.9M 443 Greenwich Street, #PHH The second most expensive sale this month was in the recent Tribeca condo conversion at 5 Beds, 6+ Baths 443 Greenwich Street. -

Download File

MANAGING TRANSPARENCY IN POST‐WAR MODERN ARCHITECTURE Makenzie Leukart Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science in Historic Preservation Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation Columbia University (May 2016) Dedication This thesis would not have been possible without the support of my advisor, Theo Prudon. His guidance and depth of knowledge about modern architecture was vital to my own chaotic process. Special thanks is given to my parents, who made this educational journey possible. I will never forget your sacrifice and your unconditional love and support. Thank you for the frequent pep talks in moments of self‐ doubt and listening to my never‐ending ramblings about my research. Especially to my mother, who tagged along on my thesis research trip and acted as both cheerleader and personal assistant throughout. To Zaw Lyn Myat and Andrea Tonc, it’s been a long 4 years to get to this point. I could not have made it through either program without your friendship, especially during the last few months as we inched towards the finish line. Additional thanks is also given to those who aided me in my research and facilitated access: Belmont Freeman, Richard Southwick, Donna Robertson, Edward Windhorst, Frank Manhan, Louis Joyner, Tricia Gilson, Richard McCoy, Erin Hawkins, Michelangelo Sabatino, Mark Sexton, Robert Brown and the entire Historic Preservation faculty and staff at Columbia. I Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................