Masculinity in Musicals: a Comparison Between the 1950S and Present Day Emily M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sherry Hoel, 773-248-4860; [email protected]

Sarah Siddons Society Contact: Sherry Hoel, 773-248-4860; [email protected] www.sarahsiddonssociety.org FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE SARAH SIDDONS SOCIETY HONORS CHICAGO’S OUTSTANDING INNOVATORS AND ARTISTS IN MUSICAL THEATRE (Chicago, IL, October 14, 2013) — The Sarah Siddons Society of Chicago recently announced that Eileen LaCario, Doug Peck, and Rachel Rockwell will be honored at Siddons’ Annual Meeting to be held at The Arts Club of Chicago on Wednesday, November 13, 2013, beginning at 11:30 am. Eileen LaCario is the Founding Member and Vice President of Broadway In Chicago which brings over one million people into the Chicago theatre district each year. Eileen has launched six theatres in Chicago including Royal George, Halsted Theatre Center, Cadillac Palace, Oriental, Bank of America Theatres and, most recently, the Broadway Playhouse. Eileen served on Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s Arts and Culture Transition Team and is past chair of the League of Chicago Theatres. She now serves on the City of Chicago Cultural Advisory Council and Choose Chicago’s Cultural Tourism Commission. Doug Peck, Music Director, has won five Jeff Awards (Porgy and Bess; Caroline, or Change; Carousel; Fiorello;Man of La Mancha) and two After Dark Awards (Guys and Dolls, Hello Again). His work has been heard in Chicago at Court Theatre, Chicago Shakespeare Theater, Writers Theatre, TimeLine Theatre Company, Northlight Theatre, the Paramount Theatre, Drury Lane Oakbrook Terrace, Porchlight Music Theatre, as well as the Ravinia Festival. Rachel Rockwell is aJeff Award winning theatre director and choreographer. Rachel’s work has been seen locally at Chicago Shakespeare Theatre, Steppenwolf, Drury Lane, The Marriott, TimeLine, Apple Tree and the Paramount Theatre. -

JERSEY BOYS and KINKY BOOTS Highlight the 2017-18 Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre Series

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press Contact: Reida York Director of Advertising and Public Relations 816.559.3847 office | 816.668.9321 cell [email protected] JERSEY BOYS and KINKY BOOTS Highlight the 2017-18 Broadway at The Orpheum Theatre Series PHOENIX, AZ – The Tony Award®-winning Best Musicals JERSEY BOYS and KINKY BOOTS highlight the 2017-18 Broadway at The Orpheum Theatre Series, presented by Theater League in Phoenix, Arizona, at the beautiful Orpheum Theatre. Season renewals and priority orders are available at BroadwayOrpheum.com or by calling 800.776.7469. “We are thrilled to bring such powerful productions to the Orpheum Theatre,” Theater League President Mark Edelman said. “We are honored to be a part of this community and we look forward to contributing to the arts and culture of Phoenix with this strong season.” The Broadway in Thousand Oaks line-up features the best of Broadway, including the international sensation, JERSEY BOYS, the high-heeled hit, KINKY BOOTS, the nostalgic standard, MUSIC MAN: IN CONCERT, and the legendary classic, A CHORUS LINE. The 2017-18 Broadway at The Orpheum Theatre Series includes the following hit musicals: MUSIC MAN: IN CONCERT December 1-3, 2017 A Broadway classic in concert featuring the nostalgic score of rousing marches, barbershop quartets and sentimental ballads, which have become popular standards. Meredith Willson’s musical comedy has been delighting audiences since 1957 and is sure to entertain every generation. Harold Hill is a traveling con man, set to pull a fast one on the people of River City, Iowa, by promising to put together a boys band and selling instruments — despite the fact he knows nothing about music. -

Brian Stokes Mitchell Outside at the Colonial

Press Contacts: Katie B. Watts Press Manager (413) 448-8084 x15 [email protected] Becky Brighenti Director of Marketing & Public Relations (413) 448-8084 x11 [email protected] For immediate release, please: Monday, July 20 at 10am Berkshire Theatre Group Announces An Intimate Performance with Two-time Tony Award-winner Brian Stokes Mitchell to Benefit Berkshire Theatre Group and a Portion of Sales to go to The Actors Fund and Black Theatre United Pittsfield, MA – Berkshire Theatre Group (BTG) and Kate Maguire (Artistic Director, CEO) are excited to announce two-time Tony Award-winner Brian Stokes Mitchell in an intimate performance and fundraiser to benefit Berkshire Theatre Group. In this very special one-night-only concert, Brian Stokes Mitchell will deliver an unforgettable performance to an audience of less than 100 people, outside under a tent at The Colonial Theatre on Labor Day Weekend, September 5 at 8pm. Dubbed “the last leading man” by The New York Times, Tony Award-winner Brian Stokes Mitchell has enjoyed a career that spans Broadway, television, film, and concert appearances with the country’s finest conductors and orchestras. He received Tony, Drama Desk, and Outer Critics Circle awards for his star turn in Kiss Me, Kate. He also gave Tony-nominated performances in Man of La Mancha, August Wilson’s King Hedley II, and Ragtime. Other notable Broadway shows include: Kiss of the Spider Woman, Jelly’s Last Jam, Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown and Shuffle Along. In 2016 he was awarded his second Tony Award, the prestigious Isabelle Stevenson Tony for his Charitable work with The Actors Fund. -

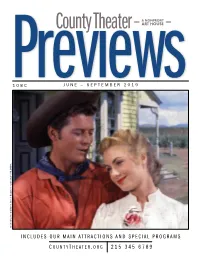

County Theater ART HOUSE

A NONPROFIT County Theater ART HOUSE Previews108C JUNE – SEPTEMBER 2019 Gordon MacRae and Shirley Jones in Rodgers & Hammerstein’s OKLAHOMA! & Hammerstein’s in Rodgers Gordon MacRae and Shirley Jones INCLUDES OUR MAIN ATTRACTIONS AND SPECIAL PROGRAMS C OUNTYT HEATER.ORG 215 345 6789 Welcome to the nonprofit County Theater The County Theater is a nonprofit, tax-exempt 501(c)(3) organization. Policies ADMISSION Children under 6 – Children under age 6 will not be admitted to our films or programs unless specifically indicated. General ............................................................$11.25 Late Arrivals – The Theater reserves the right to stop selling Members ...........................................................$6.75 tickets (and/or seating patrons) 10 minutes after a film has Seniors (62+) & Students ..................................$9.00 started. Matinees Outside Food and Drink – Patrons are not permitted to bring Mon, Tues, Thurs & Fri before 4:30 outside food and drink into the theater. Sat & Sun before 2:30 .....................................$9.00 Wed Early Matinee before 2:30 ........................$8.00 Accessibility & Hearing Assistance – The County Theater has wheelchair-accessible auditoriums and restrooms, and is Affiliated Theater Members* ...............................$6.75 equipped with hearing enhancement headsets and closed cap- You must present your membership card to obtain membership discounts. tion devices. (Please inquire at the concession stand.) The above ticket prices are subject to change. Parking Check our website for parking information. THANK YOU MEMBERS! Your membership is the foundation of the theater’s success. Without your membership support, we would not exist. Thank you for being a member. Contact us with your feedback How can you support or questions at 215 348 1878 x115 or email us at COUNTY THEATER the County Theater? MEMBER [email protected]. -

2019 Silent Auction List

September 22, 2019 ………………...... 10 am - 10:30 am S-1 2018 Broadway Flea Market & Grand Auction poster, signed by Ariana DeBose, Jay Armstrong Johnson, Chita Rivera and others S-2 True West opening night Playbill, signed by Paul Dano, Ethan Hawk and the company S-3 Jigsaw puzzle completed by Euan Morton backstage at Hamilton during performances, signed by Euan Morton S-4 "So Big/So Small" musical phrase from Dear Evan Hansen , handwritten and signed by Rachel Bay Jones, Benj Pasek and Justin Paul S-5 Mean Girls poster, signed by Erika Henningsen, Taylor Louderman, Ashley Park, Kate Rockwell, Barrett Wilbert Weed and the original company S-6 Williamstown Theatre Festival 1987 season poster, signed by Harry Groener, Christopher Reeve, Ann Reinking and others S-7 Love! Valour! Compassion! poster, signed by Stephen Bogardus, John Glover, John Benjamin Hickey, Nathan Lane, Joe Mantello, Terrence McNally and the company S-8 One-of-a-kind The Phantom of the Opera mask from the 30th anniversary celebration with the Council of Fashion Designers of America, designed by Christian Roth S-9 The Waverly Gallery Playbill, signed by Joan Allen, Michael Cera, Lucas Hedges, Elaine May and the company S-10 Pretty Woman poster, signed by Samantha Barks, Jason Danieley, Andy Karl, Orfeh and the company S-11 Rug used in the set of Aladdin , 103"x72" (1 of 3) Disney Theatricals requires the winner sign a release at checkout S-12 "Copacabana" musical phrase, handwritten and signed by Barry Manilow 10:30 am - 11 am S-13 2018 Red Bucket Follies poster and DVD, -

JERSEY BOYS Added to 2021 STAGES St

NEWS RELEASE For More Information Please Contact: Brett Murray [email protected] 636.449.5773 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE (9/21/2020) STAGES ST. LOUIS ANNOUNCES BROADWAY STAR AND BROADWAY HIT TO HEADLINE 35TH ANNIVERSARY SEASON Tony Award-Winning JERSEY BOYS and Broadway Star Diana DeGarmo headline STAGES 35th Anniversary Season. (ST. LOUIS) – STAGES St. Louis is thrilled to announce its spectacular 35th Anniversary Season! The 2021 Season includes the much requested return of the most popular show in STAGES history, ALWAYS… PATSY CLINE, the Pulitzer Prize and Tony Award-Winning masterpiece, A CHORUS LINE, the STAGES premiere of the Broadway sensation, JERSEY BOYS, and our Family Theatre Series production of the delightful A YEAR WITH FROG AND TOAD. 2021 not only marks the 35th Anniversary Season for STAGES, but also the move into the organization’s new artistic home in The Ross Family Theatre at the Kirkwood Performing Arts Center. The 40,000 square foot state-of-the-art facility features the 529-seat Ross Family Theatre, where all future productions of the Mainstage Season will play, and a flexible studio theatre, which will serve as home for the Family Theatre Series. “We could not be more excited to bring you a year of true blockbusters for our Inaugural Season at the Kirkwood Performing Arts Center!” said Executive Producer Jack Lane. “There is no better way to christen our new home at The Ross Family Theatre and welcome our audience back than with the return of ALWAYS… PATSY CLINE; the groundbreaking A CHORUS LINE; and the STAGES premiere of one of the most popular musicals in Broadway history, JERSEY BOYS.” STAGES is also overjoyed to welcome American Idol alum and Broadway star Diana DeGarmo as Patsy Cline, alongside STAGES-favorite Zoe Vonder Haar as Louise Seger in the encore of the bestselling production in STAGES’ history, ALWAYS… PATSY CLINE. -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1950S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1950s Page 86 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1950 A Dream Is a Wish Choo’n Gum I Said my Pajamas Your Heart Makes / Teresa Brewer (and Put On My Pray’rs) Vals fra “Zampa” Tony Martin & Fran Warren Count Every Star Victor Silvester Ray Anthony I Wanna Be Loved Ain’t It Grand to Be Billy Eckstine Daddy’s Little Girl Bloomin’ Well Dead The Mills Brothers I’ll Never Be Free Lesley Sarony Kay Starr & Tennessee Daisy Bell Ernie Ford All My Love Katie Lawrence Percy Faith I’m Henery the Eighth, I Am Dear Hearts & Gentle People Any Old Iron Harry Champion Dinah Shore Harry Champion I’m Movin’ On Dearie Hank Snow Autumn Leaves Guy Lombardo (Les Feuilles Mortes) I’m Thinking Tonight Yves Montand Doing the Lambeth Walk of My Blue Eyes / Noel Gay Baldhead Chattanoogie John Byrd & His Don’t Dilly Dally on Shoe-Shine Boy Blues Jumpers the Way (My Old Man) Joe Loss (Professor Longhair) Marie Lloyd If I Knew You Were Comin’ Beloved, Be Faithful Down at the Old I’d Have Baked a Cake Russ Morgan Bull and Bush Eileen Barton Florrie Ford Beside the Seaside, If You were the Only Beside the Sea Enjoy Yourself (It’s Girl in the World Mark Sheridan Later Than You Think) George Robey Guy Lombardo Bewitched (bothered If You’ve Got the Money & bewildered) Foggy Mountain Breakdown (I’ve Got the Time) Doris Day Lester Flatt & Earl Scruggs Lefty Frizzell Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo Frosty the Snowman It Isn’t Fair Jo Stafford & Gene Autry Sammy Kaye Gordon MacRae Goodnight, Irene It’s a Long Way Boiled Beef and Carrots Frank Sinatra to Tipperary -

ARSC Journal

TOSCANINI LIVE BEETHOVEN: Missa Solemnis in D, Op. 123. Zinka Milanov, soprano; Bruna Castagna, mezzo-soprano; Jussi Bjoerling, tenor; Alexander Kipnis, bass; Westminster Choir; VERDI: Missa da Requiem. Zinka Milanov, soprano; Bruna Castagna, mezzo-soprano; Jussi Bjoerling, tenor; Nicola Moscona, bass; Westminster Choir, NBC Symphony Orchestra, Arturo Toscanini, cond. Melodram MEL 006 (3). (Three Discs). (Mono). BEETHOVEN: Symphony No. 9 in D Minor, Op. 125. Vina Bovy, soprano; Kerstin Thorborg, contralto; Jan Peerce, tenor; Ezio Pinza, bass; Schola Cantorum; Arturo Toscanini Recordings Association ATRA 3007. (Mono). (Distributed by Discocorp). BRAHMS: Symphonies: No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 68; No. 2 in D, Op. 73; No. 3 in F, Op. 90; No. 4 in E Minor, Op. 98; Tragic Overture, Op. 81; Variations on a Theme by Haydn, Op. 56A. Philharmonia Orchestra. Cetra Documents. Documents DOC 52. (Four Discs). (Mono). BRAHMS: Symphony No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 68; Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, No. 2 in B Flat, Op. 83. Serenade No. 1 in D, Op. 11: First movement only; Vladimir Horowitz, piano (in the Concerto); Melodram MEL 229 (Two Discs). BRAHMS: Symphony No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 68. MOZART: Symphony No. 40 in G Minor, K. 550. TCHAIKOVSKY: Romeo and Juliet (Overture-Fantasy). WAGNER: Lohengrin Prelude to Act I. WEBER: Euryanthe Overture. Giuseppe Di Stefano Presenta GDS 5001 (Two Discs). (Mono). MOZART: Symphony No. 35 in D, K. 385 ("Haffner") Rehearsal. Relief 831 (Mono). TOSCANINI IN CONCERT: Dell 'Arte DA 9016 (Mono). Bizet: Carmen Suite. Catalani: La Wally: Prelude; Lorelei: Dance of the Water ~· H~rold: Zampa Overture. -

ANTA Theater and the Proposed Designation of the Related Landmark Site (Item No

Landmarks Preservation Commission August 6, 1985; Designation List 182 l.P-1309 ANTA THFATER (originally Guild Theater, noN Virginia Theater), 243-259 West 52nd Street, Manhattan. Built 1924-25; architects, Crane & Franzheim. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1024, Lot 7. On June 14 and 15, 1982, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the ANTA Theater and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 5). The hearing was continued to October 19, 1982. Both hearings had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Eighty-three witnesses spoke in favor of designation. Two witnesses spoke in opposition to designation. The owner, with his representatives, appeared at the hearing, and indicated that he had not formulated an opinion regarding designation. The Commission has received many letters and other expressions of support in favor of this designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The ANTA Theater survives today as one of the historic theaters that symbolize American theater for both New York and the nation. Built in the 1924-25, the ANTA was constructed for the Theater Guild as a subscription playhouse, named the Guild Theater. The fourrling Guild members, including actors, playwrights, designers, attorneys and bankers, formed the Theater Guild to present high quality plays which they believed would be artistically superior to the current offerings of the commercial Broadway houses. More than just an auditorium, however, the Guild Theater was designed to be a theater resource center, with classrooms, studios, and a library. The theater also included the rrost up-to-date staging technology. -

American Music Research Center Journal

AMERICAN MUSIC RESEARCH CENTER JOURNAL Volume 19 2010 Paul Laird, Guest Co-editor Graham Wood, Guest Co-editor Thomas L. Riis, Editor-in-Chief American Music Research Center College of Music University of Colorado Boulder THE AMERICAN MUSIC RESEARCH CENTER Thomas L. Riis, Director Laurie J. Sampsel, Curator Eric J. Harbeson, Archivist Sister Mary Dominic Ray, O.P. (1913–1994), Founder Karl Kroeger, Archivist Emeritus William Kearns, Senior Fellow Daniel Sher, Dean, College of Music William S. Farley, Research Assistant, 2009–2010 K. Dawn Grapes, Research Assistant, 2009–2011 EDITORIAL BOARD C. F. Alan Cass Kip Lornell Susan Cook Portia Maultsby Robert R. Fink Tom C. Owens William Kearns Katherine Preston Karl Kroeger Jessica Sternfeld Paul Laird Joanne Swenson-Eldridge Victoria Lindsay Levine Graham Wood The American Music Research Center Journal is published annually. Subscription rate is $25.00 per issue ($28.00 outside the U.S. and Canada). Please address all inquiries to Lisa Bailey, American Music Research Center, 288 UCB, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309-0288. E-mail: [email protected] The American Music Research Center website address is www.amrccolorado.org ISSN 1058-3572 © 2010 by the Board of Regents of the University of Colorado INFORMATION FOR AUTHORS The American Music Research Center Journal is dedicated to publishing articles of general interest about American music, particularly in subject areas relevant to its collections. We welcome submission of articles and pro- posals from the scholarly community, ranging from 3,000 to 10,000 words (excluding notes). All articles should be addressed to Thomas L. Riis, College of Music, University of Colorado Boulder, 301 UCB, Boulder, CO 80309-0301. -

A Love Affair with Danger

A Love Affair With Danger Bill Hastings has been in Norway about 20 times. He was first hired by The Norwegian University College of Dance in 1991 to do Dancin’ Man for their 25th anniversary. Now, he’s back at The Norwegian University College of Dance to rehearse The Rich Man’s Frug for the 50th anniversary. Can you tell me about your career as a dancer? - I went to college on a full music scholarship. I was a self-taught percussionist who dreamed of playing in a classical orchestra; however, I graduated with a degree in theatre. While in college, a friend of mine came to me and said there was an audition for a local production of the musical “Paint your Wagon”. He encouraged me to audition, and so I did. Quite surprisingly I was hired for the job. A whole new world opened to me. The combination of music, theatre and dance was thrilling. I was hooked. A lifelong career as dancer, choreographer and teacher was to follow. About the same time, I saw a film of Martha Graham’s Seraphic Dialogue; and I thought, I want to do THAT - the beautiful, powerful movement; the iconic design; and, the theatrical artfulness. However, it was the bright lights of musical theatre that ultimately won me over. You seem like you like what you are doing. Is that right? - I love what I’m doing; but, it also frightens me. It demands much from the heart, the spirit, the intellect and the body (as with most athletes, age is a constant sparring partner). -

THE BALLET Corps De Ballet of Metropolitan, Chicago and San Francisco Draw up Schedules of Minimum Pay and Conditions of Employment

A~MA Official Organ of the AMERICAN GUILD OF MUSICAL ARTISTS, INC. 576 Fifth Avenue, New York, N. Y. Telephone: LOngacre 3-6223 Branch of the ASSOCIATED ACTORS AND ARTISTES OF AMERICA FEBRUARY~APRIL, 1939 VOLUME IV, Nos. 2, 3, 4 Representatives HolJywood Office: San Francisco: Chicago; ERNEST CHARLBS, Asst. Exec. Seq. VIC CONNORS-THBODOlUl HALE LEO CURLEY 6331 HollyWood Boulevard 220 Bush Street 162 East Ohio Street Officers: Board of Governors: ',LAWltBNCl!• TIBBETT • • ZLATKO BALOKOVIC ERNST LERT ': President WALTER DAMlt9sCH RUTH BRETON LAURITZ MELCHIOR RUDOLPH .GANZ JASCHA HEI~~ FlIANK CHAPMAN JAMES MELTON '1st Vice.PresMent RICHARD CROOKS EzlO PINZA HOWARD HANSON RICHARD BO'Nl'lLU MISCHA ELMAN ERNEST HUTCHESON 2nd Vi&e.~Jitlenl EVA GAUTHIER SERGE KOUSSllVIT?..KY' MARG CHARLES HACKETT Jrd esitli:nJ LEHMANN EDWARD HARRIs FlIAN" .SHERIDAN, ELISABtrR H()llPF'm ;;JOHN MCCORMACK 4th' Tliie"President JULIUS 'HUEHN DANIBL HARRIS EDWIN HUGHES Jth Vice·President JOS!; ITUIlDI Q MARro Fl!.EDERICK JAGBL MAlUIK WINDHBD( r ding Secretary EFlUIM ZrMBALIST PlIAnt( LA FoRGE TrealNl'er • LEO PtsCHBR Edited by L. T. CARR ExecNtitle Secretary Editorial Advisory Committee: .Hll'NlI!t JAl'l'E EDWARD HAl!.l!.IS, Chairman ~, CfIfI1Htil RICHARD BONELLI LEO PlSCHlIR GUILD • • • N THIS issue is reported the signing of agreements be I tween AGMA and NBC Artists Service and Columbia authority of an Artists' union in regula Concerts Corporation, the two largest managers of musical and the policies pursued in the concert a~ts in this country. The contracts are the full and final has implications of the grave~t importance, 'not ft)1~fthe symbol of the new order which began in American musical artists directly m~naged by the .~;chains, but £ot~al1milsicaf Hfe with the formation of AGMA and the beginning of its artists.