Microsoft Corporation Vs. Sun Microsystems, Inc., U.S. Court Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hardware & Software Standards

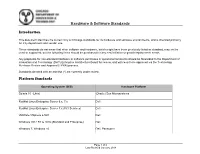

Hardware & Software Standards Introduction This document identifies the current City of Chicago standards for its hardware and software environments, and is intended primarily for City department and vendor use. These standards do not mean that other software and hardware, which might have been previously listed as standard, may not be used or supported, but the following items should be purchased for any new initiative or growth/replacement needs. Any proposals for non-standard hardware or software purchases or questions/comments should be forwarded to the Department of Innovation and Technology (DoIT) Enterprise Architecture Board for review, and will need to be approved via the Technology Purchase Review and Approval (TPRA) process. Standards denoted with an asterisk (*) are currently under review. Platform Standards Operating System (O/S) Hardware Platform Solaris 10 (Unix) (Oracle) Sun Microsystems RedHat Linux Enterprise Server 6.x, 7.x Dell RedHat Linux Enterprise Server 7.x (PCI Services) Dell VMWare VSphere 6.5U1 Dell Windows 2012 R2 & 2016 (Standard and Enterprise) Dell Windows 7, Windows 10 Dell, Panasonic Page 1 of 6 Last Revised January 2018 Hardware & Software Standards Enterprise Services Type Windows 2008 Server All other platforms Oracle Enterprise 11gR2, 12cR1; Postgres 9.x or 10.x (EnterpriseDB or Database N/A community) Print O/S n/a File O/S n/a Email Exchange 2016 / Office365 n/a Desktops, Laptops, & Tablets Type Model Standard Users Dell OptiPlex 5050 SFF, Dell OptiPlex 7450 All-In-One Mobile User Latitude 12 Rugged Extreme Latitude 14 Rugged 5414 Latitude 12 2 in 1 with case and Doc Latitude 5480 14" Laptop 6th gen proc High-End Workstation Dell Precision T5810 Laptop Accessories Docking- For the E-5470 units, Dell Business Dock - WD15 with 130W Adapter Monitor Dell 23 Monitor – P2317H Page 2 of 6 Last Revised January 2018 Hardware & Software Standards Printing and Scanning The Department of Fleet and Facility Management (2FM) oversees print services for the City of Chicago. -

Java Programming Language, Java SE 6

Java Programming Language, Java SE 6 Electronic Presentation SL-275-SE6 REV G.2 D61748GC11 Edition 1.1 Copyright © 2008, 2010, Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. Disclaimer This document contains proprietary information, is provided under a license agreement containing restrictions on use and disclosure, and is protected by copyright and other intellectual property laws. You may copy and print this document solely for your own use in an Oracle training course. The document may not be modified or altered in any way. Except as expressly permitted in your license agreement or allowed by law, you may not use, share, download, upload, copy, print, display, perform, reproduce, publish, license, post, transmit, or distribute this document in whole or in part without the express authorization of Oracle. The information contained in this document is subject to change without notice. If you find any problems in the document, please report them in writing to: Oracle University, 500 Oracle Parkway, Redwood Shores, California 94065 USA. This document is not warranted to be error-free. Sun Microsystems, Inc. Disclaimer This training manual may include references to materials, offerings, or products that were previously offered by Sun Microsystems, Inc. Certain materials, offerings, services, or products may no longer be offered or provided. Oracle and its affiliates cannot be held responsible for any such references should they appear in the text provided. Restricted Rights Notice If this documentation is delivered to the U.S. Government or anyone using the documentation on behalf of the U.S. Government, the following notice is applicable: U.S. -

GOOGLE LLC V. ORACLE AMERICA, INC

(Slip Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2020 1 Syllabus NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus GOOGLE LLC v. ORACLE AMERICA, INC. CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FEDERAL CIRCUIT No. 18–956. Argued October 7, 2020—Decided April 5, 2021 Oracle America, Inc., owns a copyright in Java SE, a computer platform that uses the popular Java computer programming language. In 2005, Google acquired Android and sought to build a new software platform for mobile devices. To allow the millions of programmers familiar with the Java programming language to work with its new Android plat- form, Google copied roughly 11,500 lines of code from the Java SE pro- gram. The copied lines are part of a tool called an Application Pro- gramming Interface (API). An API allows programmers to call upon prewritten computing tasks for use in their own programs. Over the course of protracted litigation, the lower courts have considered (1) whether Java SE’s owner could copyright the copied lines from the API, and (2) if so, whether Google’s copying constituted a permissible “fair use” of that material freeing Google from copyright liability. In the proceedings below, the Federal Circuit held that the copied lines are copyrightable. -

Sun Glassfish Enterprise Server V3 Preludetroubleshooting Guide

Sun GlassFish Enterprise Server v3 PreludeTroubleshooting Guide Sun Microsystems, Inc. 4150 Network Circle Santa Clara, CA 95054 U.S.A. Part No: 820–6823–10 November 2008 Copyright 2008 Sun Microsystems, Inc. 4150 Network Circle, Santa Clara, CA 95054 U.S.A. All rights reserved. Sun Microsystems, Inc. has intellectual property rights relating to technology embodied in the product that is described in this document. In particular, and without limitation, these intellectual property rights may include one or more U.S. patents or pending patent applications in the U.S. and in other countries. U.S. Government Rights – Commercial software. Government users are subject to the Sun Microsystems, Inc. standard license agreement and applicable provisions of the FAR and its supplements. This distribution may include materials developed by third parties. Parts of the product may be derived from Berkeley BSD systems, licensed from the University of California. UNIX is a registered trademark in the U.S. and other countries, exclusively licensed through X/Open Company, Ltd. Sun, Sun Microsystems, the Sun logo, the Solaris logo, the Java Coffee Cup logo, docs.sun.com, Enterprise JavaBeans, EJB, GlassFish, J2EE, J2SE, Java Naming and Directory Interface, JavaBeans, Javadoc, JDBC, JDK, JavaScript, JavaServer, JavaServer Pages, JMX, JSP,JVM, MySQL, NetBeans, OpenSolaris, SunSolve, Sun GlassFish, Java, and Solaris are trademarks or registered trademarks of Sun Microsystems, Inc. or its subsidiaries in the U.S. and other countries. All SPARC trademarks are used under license and are trademarks or registered trademarks of SPARC International, Inc. in the U.S. and other countries. Products bearing SPARC trademarks are based upon an architecture developed by Sun Microsystems, Inc. -

CDC: Java Platform Technology for Connected Devices

CDC: JAVA™ PLATFORM TECHNOLOGY FOR CONNECTED DEVICES Java™ Platform, Micro Edition White Paper June 2005 2 Table of Contents Sun Microsystems, Inc. Table of Contents Introduction . 3 Enterprise Mobility . 4 Connected Devices in Transition . 5 Connected Devices Today . 5 What Users Want . 5 What Developers Want . 6 What Service Providers Want . 6 What Enterprises Want . 6 Java Technology Leads the Way . 7 From Java Specification Requests… . 7 …to Reference Implementations . 8 …to Technology Compatibility Kits . 8 Java Platform, Micro Edition Technologies . 9 Configurations . 9 CDC . 10 CLDC . 10 Profiles . 11 Optional Packages . 11 A CDC Java Runtime Environment . 12 CDC Technical Overview . 13 CDC Class Library . 13 CDC HotSpot™ Implementation . 13 CDC API Overview . 13 Application Models . 15 Standalone Applications . 16 Managed Applications: Applets . 16 Managed Applications: Xlets . 17 CLDC Compatibility . 18 GUI Options and Tradeoffs . 19 AWT . 19 Lightweight Components . 20 Alternate GUI Interfaces . 20 AGUI Optional Package . 20 Security . 21 Developer Tool Support . 22 3 Introduction Sun Microsystems, Inc. Chapter 1 Introduction From a developer’s perspective, the APIs for desktop PCs and enterprise systems have been a daunting combination of complexity and confusion. Over the last 10 years, Java™ technology has helped simplify and tame this world for the benefit of everyone. Developers have benefited by seeing their skills become applicable to more systems. Users have benefited from consistent interfaces across different platforms. And systems vendors have benefited by reducing and focusing their R&D investments while attracting more developers. For desktop and enterprise systems, “Write Once, Run Anywhere”™ has been a success. But if the complexities of the desktop and enterprise world seem, well, complex, then the connected device world is even scarier. -

Solaris 10 OS on AMD Opteron Processor-Based Systems

Solaris™ 10 OS on AMD Opteron™ Processor-based Systems < A powerful combination for your business Sun and AMD take x64 computing to a new level with the breakthrough performance of AMD Opteron™ processor-based systems combined with the Solaris™ 10 OS — the most advanced operating system on the planet. By combining the best of free and open source software with the most powerful industry-standard platforms, customers can take advantage of the most robust and secure, yet economical Web, database, and application servers. A unique partnership Price/performance Coengineering and technology collaboration World-record performance Sun and AMD software engineers work jointly Leveraging more than 20 years of Symmetric on a range of codevelopment efforts including Multiprocessing (SMP) expertise, Sun has future development of HyperTransport, virtu- tuned and optimized Solaris 10 for the AMD alization, fault management, compiler perform- Opteron platform to deliver exceptional ance, and other ways Solaris may take advantage performance and near-linear scalability. For Highlights of the AMD Opteron architecture. Solaris 10 enterprises with demanding compute, net- • Supports the latest generation 5/08 also includes support for the latest gener- work, and Web applications, the combination of AMD x64 processors ation of AMD x64 processors and UltraSPARC of Solaris 10 and AMD Opteron processor-based • PowerNow! enhancements CMT systems. systems is often an ideal fit. Dozens of perform- provide additional power man- ance and price/performance world record agement capabilities Growing the Solaris™ OS ecosystem for AMD64 benchmarks demonstrate this exceptional • Remote client display virtualiztion Sun and AMD are working together with key combination. Solaris 10 has set more than • Solaris Trusted Extensions optimi- target ISVs, system builders, and independent 50 world records, employing various industry- zations for better interoperability hardware vendors (IHVs) to fuel growth of the standard benchmarks or workload scenarios and security Solaris 10 ecosystem around AMD64. -

100% Pure Java Cookbook Use of Native Code

100% Pure Java Cookbook Guidelines for achieving the 100% Pure Java Standard Revision 4.0 Sun Microsystems, Inc. 901 San Antonio Road Palo Alto, California 94303 USA Copyrights 2000 Sun Microsystems, Inc. All rights reserved. 901 San Antonio Road, Palo Alto, California 94043, U.S.A. This product and related documentation are protected by copyright and distributed under licenses restricting its use, copying, distribution, and decompilation. No part of this product or related documentation may be reproduced in any form by any means without prior written authorization of Sun and its licensors, if any. Restricted Rights Legend Use, duplication, or disclosure by the United States Government is subject to the restrictions set forth in DFARS 252.227-7013 (c)(1)(ii) and FAR 52.227-19. The product described in this manual may be protected by one or more U.S. patents, foreign patents, or pending applications. Trademarks Sun, the Sun logo, Sun Microsystems, Java, Java Compatible, 100% Pure Java, JavaStar, JavaPureCheck, JavaBeans, Java 2D, Solaris,Write Once, Run Anywhere, JDK, Java Development Kit Standard Edition, JDBC, JavaSpin, HotJava, The Network Is The Computer, and JavaStation are trademarks or registered trademarks of Sun Microsystems, Inc. in the U.S. and certain other countries. UNIX is a registered trademark in the United States and other countries, exclusively licensed through X/Open Company, Ltd. All other product names mentioned herein are the trademarks of their respective owners. Netscape and Netscape Navigator are trademarks of Netscape Communications Corporation in the United States and other countries. THIS PUBLICATION IS PROVIDED “AS IS” WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EITHER EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, THE IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE, OR NON-INFRINGEMENT. -

Tco Comparison: 2-Processor Dell and Sun Servers

TCO COMPARISON: 2-PROCESSOR DELL AND SUN SERVERS OUR FINDINGS OUR PROCESS The latest, most powerful Dell PowerEdge servers We used the industry-standard SPECjbb2005 provide better performance and lower total cost of benchmark to measure the performance and ownership (TCO) than Sun SPARC Enterprise power usage of the Dell PowerEdge R810 server. servers. In Principled Technologies’ tests in our We compared those results to publicly available labs, the Dell PowerEdge R810 server delivered SPECjbb2005 results and power measurements for higher performance results than the publicly the Sun server to identify performance-equivalent available benchmark scores of the Sun SPARC configurations of the two servers and estimate Enterprise T5240 servers. This better performance their energy costs. We calculated the 3-year TCO of of the Dell servers, along with much lower those configurations using energy cost estimates, hardware costs and lower annual costs, leads to a server prices from Dell and the Oracle Web site, significant TCO advantage for the Dell solution. and our own estimates of costs for migration, facilities, software, and server management. MARCH 2010 A PRINCIPLED TECHNOLOGIES ANALYSIS Commissioned by Dell Corp. PROJECT OVERVIEW We estimated costs for a hypothetical enterprise migrating from end-of-life Sun SPARC servers running Oracle on Solaris. The enterprise wants a solution that meets performance goals and provides the lowest 3- year TCO and is considering either the latest, most powerful Dell PowerEdge servers or Sun SPARC Enterprise servers as the replacement. Expected benefits of this server replacement project also include savings in data center space and power consumption. The migration will involve acquiring hardware, upgrading to the Oracle 11G version, and, in the case of the Dell solution, changing both hardware architecture and operating systems. -

Java (Software Platform) from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Not to Be Confused with Javascript

Java (software platform) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Not to be confused with JavaScript. This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone , or spelling. You can assist by editing it. (February 2016) Java (software platform) Dukesource125.gif The Java technology logo Original author(s) James Gosling, Sun Microsystems Developer(s) Oracle Corporation Initial release 23 January 1996; 20 years ago[1][2] Stable release 8 Update 73 (1.8.0_73) (February 5, 2016; 34 days ago) [±][3] Preview release 9 Build b90 (November 2, 2015; 4 months ago) [±][4] Written in Java, C++[5] Operating system Windows, Solaris, Linux, OS X[6] Platform Cross-platform Available in 30+ languages List of languages [show] Type Software platform License Freeware, mostly open-source,[8] with a few proprietary[9] compo nents[10] Website www.java.com Java is a set of computer software and specifications developed by Sun Microsyst ems, later acquired by Oracle Corporation, that provides a system for developing application software and deploying it in a cross-platform computing environment . Java is used in a wide variety of computing platforms from embedded devices an d mobile phones to enterprise servers and supercomputers. While less common, Jav a applets run in secure, sandboxed environments to provide many features of nati ve applications and can be embedded in HTML pages. Writing in the Java programming language is the primary way to produce code that will be deployed as byte code in a Java Virtual Machine (JVM); byte code compil ers are also available for other languages, including Ada, JavaScript, Python, a nd Ruby. -

APPLE COMPUTER, INC. AGREES to ACQUIRE Next SOFTWARE INC

Apple/NeXT Merge PRESS RELEASE APPLE COMPUTER, INC. AGREES TO ACQUIRE NeXT SOFTWARE INC. Acquisition Confirms New Open Apple; Steve Jobs Returns to Apple; Complementary Technology Offers New Opportunities for Apple in Enterprise, Internet, and Software Markets CUPERTINO, Calif.--Dec. 20, 1996--Apple Computer, Inc. today announced its intention to purchase NeXT Software Inc., in a friendly acquisition for $400 million. Pending regulatory approvals, all NeXT products, services, and technology research will become part of Apple Computer, Inc. As part of the agreement, Steve Jobs, Chairman and CEO of NeXT Software, will return to Apple--the company he co-founded in 1976--reporting to Dr. Gilbert F. Amelio, Apple's Chairman and CEO. The acquisition will bring together Apple's and NeXT's innovative and complementary technology portfolios and significantly strengthens Apple's position as a company advancing industry standards. Apple's leadership in ease-of-use and multimedia solutions will be married to NeXT's strengths in development software and operating environments for both the enterprise and Internet markets. NeXT's object oriented software development products will contribute to Apple's goal of creating a differentiated and profitable software business, with a wide range of products for enterprise, business, education, and home markets. Using NeXT technology to embrace open industry standards Apple Computer, Inc. believes the acquisition will allow the Company to further develop industry alliances as the Internet/intranet market evolves. Apple anticipates that NeXT's expertise in next-generation operating system design will allow elements of the NEXTSTEP operating system to become integral features of Mac OS--providing developers a compelling OS foundation on which to build next generation software solutions. -

Legal Notice

Altera Digital Library September 1996 P-CD-ADL-01 Legal Notice This CD contains documentation and other information related to products and services of Altera Corporation (“Altera”) which is provided as a courtesy to Altera’s customers and potential customers. By copying or using any information contained on this CD, you agree to be bound by the terms and conditions described in this Legal Notice. The documentation, software, and other materials contained on this CD are owned and copyrighted by Altera and its licensors. Copyright © 1994, 1995, 1996 Altera Corporation, 2610 Orchard Parkway, San Jose, California 95134, USA and its licensors. All rights reserved. You are licensed to download and copy documentation and other information from this CD provided you agree to the following terms and conditions: (1) You may use the materials for informational purposes only. (2) You may not alter or modify the materials in any way. (3) You may not use any graphics separate from any accompanying text. (4) You may distribute copies of the documentation available on this CD only to customers and potential customers of Altera products. However, you may not charge them for such use. Any other distribution to third parties is prohibited unless you obtain the prior written consent of Altera. (5) You may not use the materials in any way that may be adverse to Altera’s interests. (6) All copies of materials that you copy from this CD must include a copy of this Legal Notice. Altera, MAX, MAX+PLUS, FLEX, FLEX 10K, FLEX 8000, FLEX 8000A, MAX 9000, MAX 7000, -

Google V. Oracle and the Future of Software Development

Google v. Oracle and the Future of Software Development By Robert S. Rigg and Sudip K. Mitra June 25, 2019 The decade-old battle between two technology powerhouses—Google and Oracle—potentially reshaping the future of software will now continue into the Supreme Court’s next term. 1 Referred to in the media as the copyright lawsuit of the decade, Google LLC v. Oracle America Inc., involves important issues related to the future of software development and restrictions on software interoperability. At the center of the dispute is the copyrightability of software interfaces—particularly Java language’s application programming interfaces (APIs) that allow third-party programs to interact with the software. Software interfaces convey information and instructions between computer programs and platforms (the digital equivalent of an electrical outlet or a car’s steering wheel). Sun Microsystems originally developed the Java language and the APIs. 2 In 2005, Google and Sun began discussing a partnership that would have allowed Google to adapt the Java platform for smartphones. Google’s plan was to incorporate Java’s Standard Edition (SE) programming libraries (including the APIs) into the Android operating system. In 2010, Oracle purchased Sun Microsystems and acquired ownership of Java’s SE libraries and the APIs. Meanwhile, negotiations among Google/Sun/Oracle went nowhere and no agreement was ever reached. In the absence of such agreement, Google used some of the Java APIs for customizing its Android platform. Oracle sued Google claiming that Google copied the structure, sequence and organization of the software code for 37 packages in its Java API, thereby infringing its Java copyrights.