Community Food Security in Pictou Landing 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Community Visitor Information Centre's in Nova Scotia, 2021

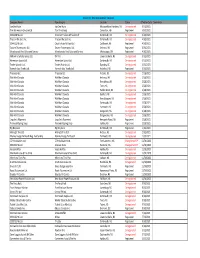

Community Visitor Information Centre's in Nova Scotia, 2021 To send literature to the Visitor Information Centres, please contact the individual VIC for instructions (time/days, delivery address, contact) Last Update July 26, 2021 VIC Name Physical Civic Location VIC Phone VIC Email Service Annapolis Royal VIC 24 Drury Lane, Annapolis Royal NS, 902-532-5454 [email protected] Open B0S 1A0 Antigonish VIC 283 Main St, Antigonish NS, B2G 2C3 902-863-4921 [email protected] Open Baddeck VIC (Victoria County) 454 Chebucto St, Baddeck NS, B0E 902-295-1911 [email protected] Open 1B0 om Barrington VIC 2447 Hwy 3, Barrington NS, B0W 1E0 902-637-2015 / [email protected]; Open 902-903-0494 satwood@barringtonmunicipality. com Bear River VIC 1884 Clementsvale Rd, Bear River NS, 902-467-0422 [email protected] Open B0S 1B0 Berwick VIC 173 Commercial St, Berwick NS, B0P 902-538-9229 [email protected] Open 1E0 Blockhouse VIC 125 B Cornwall Rd, Blockhouse NS, 902-530-4677 [email protected]; Open B0J 1E0 [email protected] Bridgetown VIC 230 Granville St.W, Bridgetown NS, 902-665-5150 [email protected] Open B0S 1C0 Caledonia VIC 9874 Hwy 8, Caledonia, Queens Co 902-682-2470 [email protected] Open NS, B0T 1B0 Canso VIC 1297 Union St, Canso NS, B0H 1H0 902-366-2170 [email protected], Open [email protected] o.ca Chester VIC https://tourismchester.ca/experience/tou 902-275-4161 [email protected], Business rism-ambassadors [email protected] Ambassador Kiosks Cheticamp VIC 15584 Cabot Trail, Cheticamp NS, B0E 902-224-2642 [email protected] 1H0 Clare VIC 23 Lighthouse Rd, Universite Sainte- 902-769-2345 [email protected] Open Anne, Church Point NS, B0W 1M0 Digby VIC 110 Montague Row, Digby NS, B0V 902-245-5714 / 1- [email protected] Open 1A0 888-463-4429 Economy - Cliffs of Fundy Welcome 3246 Nova Scotia Trunk 2, Economy 902 647-2312 [email protected] Open Centre NS, B0M 1J0 Guysborough VIC 106 Church St. -

NS Royal Gazette Part I

Nova Scotia Published by Authority PART 1 VOLUME 220, NO. 4 HALIFAX, NOVA SCOTIA, WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 26, 2011 Land Transactions by the Province of Schedule “A” Nova Scotia pursuant to the Ministerial Notice of Parcel Registration under the Land Transaction Regulations (MLTR) for Land Registration Act the period February 13, 2009 to October 14, 2010 TAKE NOTICE that ownership of the property known as Name/Grantor Year Fishery Limited PID 20244828, located at 700 Willow Street, Truro, Type of Transaction Grant Colchester County, Nova Scotia, has been registered Location Hacketts Cove under the Land Registration Act, in whole or in part on Halifax County the basis of adverse possession, in the name of Allen Area 1195 square metres Dexter Symes. Document Number 92763250 recorded February 13, 2009 NOTICE is being provided as directed by the Registrar General of Land Titles in accordance with clause Name/Grantor Mariners Anchorage Residents 10(10)(b) of the Land Registration Administration Association Regulations. For further information, you may contact Type of Transaction Grant the lawyer for the registered owner, noted below. Location Glen Haven, Halifax County Area 192 square metres TO: The Heirs of Ernest MacKenzie or other persons Document Number 96826046 who may have an interest in the above-noted property. recorded September 21, 2010 DATED at Pictou, Pictou County, Nova Scotia, this Name/Grantor Welsford, Barbara 17th day of January, 2011. Type of Transaction Grant Location Oakland, Halifax County Ian H. MacLean Area 174 square metres -

NSMB 1927 Vol.6(12) 1-42 OCR 300Dpi.Pdf

THE NOVA SCOTIA MEDICAL BULLETIN l THE WORK OF A LIFETIME Have you Safeguarded it? Have you provided enough protection to secure it for your family after your own administration has ceased? Prudent men of all times have left behind them carefully drawn Wills. The need for such protection was never greater than it is to-day. It is your duty to your family to have your Will drawn and drawn correctly. A slip in phrasing or punctuation may change the whole meaning of a clause in your Will. Do not have a homemade Will- it may prove fatal to your family. Our officials are experienced in matters of this kind and will be pleased to discuss your Will with you and have it drawn by a solicitor. Ube 1Ro\"a Scotia Urust <tompan~ EXECUTOR TRUSTEE GUARDIAN 162 Hollis Street Halifax, N. S. MOIRS LIMITED 6 Y.2 p. c. First Mortgage Sinking Fund Bonds. Dated Jan. 1, 1926 Maturing Jan. l, 1946 These Bonds are part of an additional issue of $350,000.00, made by Moirs Ltd. to provide a portion of the cost (amounting to approximately $550,000) of the recent addition to the plant in the city of Halifax. Assets: Combined, fixed and net assets equivalent to $2400 for each $1 ,000 first mortgage bond outstanding, including this issue. Earnings: For the year ended December 31, 1926, equivalent to 2.96 times the annual interest requirement of first mortgage bonds including t his issue. We recommend the purchase of this Security. PRICE: 103 p. c. and interest to Y IELD over 6 1-4 p. -

Simon Gibbons

Simon Gibbons Simon Gibbons was the first Inuit priest in the Church of England. He was born on June 21, 1851 in Forteau, Labrador – about 13 km north east of the Quebec border. His mother died in childbirth. At five years old Simon was sent by the Anglican Missionary in Forteau to the Church of England Widows and Orphans Asylum (CEWOA) in St. John’s, Newfoundland. While there, he showed “intellect of no ordinary degree” and was placed in the Church of England Academy when he was nine. Two years later, Sophia Mountain, the Lady Superintendent of the orphanage (CEWOA) took Simon under her care. Then, when Simon was 15, she married Edward Field, the Bishop of Newfoundland in 1867. So, in just a few years, Simon went from being an orphan to the Bishop’s Court. Following his graduation from the Academy, Simon began to prepare to take an active part in the ministry of the Church. He became part of a group who trained and worked as Lay Readers, Teachers, and Catechists in Newfoundland’s outports. On one occasion during this time, he was leading a Sunday morning Service in the large kitchen of a fisherman’s house. It was packed with people, and Simon was standing in the place of honour by the roaring stove. Just as he began the sermon, the lady of the house stood up in her place, by the door, waving her raised hand. “Hold a minute, Parson!” she cried. Simon stopped. The lady continued, “Sal, the puddin’!” Sal, seated on the other side of the stove, arose, took from the dresser the Sunday dumpling in its cloth and popped it into the pot boiling on the stove. -

Prince Edward Is

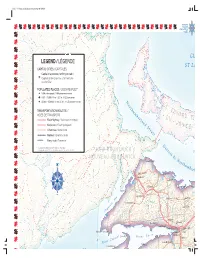

(1,1) -1- Nova Scotia.indd 2015-07-07 9:13 AM G U LEGEND / LÉGENDE ST LA CAPITAL CITIES / CAPITALES Capital of a province, territory or state / Capitale d’une province, d’un territoire ou d’un État POPULATED PLACES / LIEUX PEUPLÉS* 1,000 or less people / 1 000 personnes ou moins P 1,001 - 25,000 / Entre 1 001 et 25 000 personnes R 25,001 - 250,000 / Entre 25 001 et 250 000 personnes N I N o C r E t h Î TRANSPORTATION ROUTES / u L E E D VOIES DE TRANSPORT m - WA b e R D Major highway / Autoroute principale r l D U I S a n - P Major road / Route principale d R I N S t C E - Other road / Autre route r a i t Railway / Chemins de fer Ferry route / Traversier / D * population numbers from 2011 Census of Canada / é La population en chiffres selon le Recensement du Canada de 2011. NEW BRUNSWICK / t r o i NOUVEAU-BRUNSWICK t d e Tidnish Bridge N o r t N h u m b e r l East Amherst Pugwash Amherst Wallace Oxford Brule Corner Rive Joggins Springhill a y West New Annan The Falls B o Southampton c t n e Earltown i g C h Debert Bass River Belmont Parrsboro Great Village Central Onslow Bible Hill Advocate Harbour Truro Heights Truro i n Millbrook l Scots Bay a s B a s n e M i n Noel Hilden h a n Sp C i n a s South Maitland M Walton Halls Harbour d y (2,1) -1- Nova Scotia.indd 2015-07-07 9:13 AM GULF OF LAWRENCE Cape North Pleasant Bay Neils Harbour GOLFE DU SAINT-LAURENT Ingonish Chéticamp Ingonish Beach Cabot Strait / Plateau Détroit de Cabot I S L A N D Cape Breton E - Margaree Forks É D O U A R D Island Alder Point Inverness Florence New Waterford St. -

Municipal Property Taxation in Nova Scotia

MUNICIPAL PROPERTY TAXATION IN NOVA SCOTIA A report by Harry Kitchen and Enid Slack for the Property Valuation Services Corporation Union of Nova Scotia Municipalities Association of Municipal Administrators April 2014 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 4 A. Criteria for Evaluating the Property Tax 12 B. Background on Municipal Finance in Nova Scotia 13 C. Inter-provincial Comparison of Property Taxation 17 a. General Assessment Categories and Tax Rate Structure 17 b. Property Taxes and School Funding 18 c. Assessment Administration 18 d. Frequency of Assessment 19 e. Limits on the Impact of a Reassessment 20 f. Exemptions 20 g. Payments in Lieu of Taxes 21 h. Treatment of Machinery and Equipment 22 i. Treatment of Linear Properties 22 j. Business Occupancy Taxes 23 k. Property Tax Relief Programs 23 l. Property Tax Incentives 24 D. Property Taxation in Nova Scotia 26 a. Assessment Base 26 b. Tax Rates 34 E. Concerns and Issues Raised about Property Taxes in Nova Scotia 39 a. Assessment Issues 39 1. Area-based or value-based assessment 39 2. Exempt properties and payments in lieu 42 3. Lag between assessment date and implementation 44 4. Volatility 45 b. Property Taxation Issues 50 5. Capping 50 6. Commercial versus residential property taxation 60 7. Tax incentives – should property taxes be used to stimulate economic development? 70 8. Should provincial property taxes be used to fund education? 72 9. Tax treatment of agricultural and resource properties no longer used for those purposes 74 10. Urban/rural tax differentials 76 F. Summary of Recommendations 77 2 References 79 Appendix A: Inter-provincial Comparisons 82 Appendix B: Stakeholder Consultations 96 3 Executive Summary The purpose of this study is to evaluate the effectiveness of the current property tax system in Nova Scotia and suggest improvements. -

Results of a Well Water Quality Survey in Eastern Shelburne County

Report of Activities 2015 29 Results of a Well Water Quality Survey in Eastern Shelburne County N. Drage1, J. Drage, E. Tipton2 and E. Hartley2 Introduction groundwater moves inland. It can be caused by any process that reduces or reverses the hydraulic gradient near the coast, including sea-level rise, The majority of residents in Shelburne County rely increased water well pumping and declining on private water wells for their drinking water. groundwater recharge rates. Wells that are located Many of these wells are located near the coast and near the coast where saltwater intrusion is have the potential to be affected by saltwater occurring will experience higher salt levels and intrusion. Climate change is expected to increase may become so salty that they must be abandoned. the risk of saltwater intrusion into coastal aquifers because of rising sea levels and changes to Saltwater intrusion occurs in coastal areas precipitation patterns. As a first step towards throughout the world and is expected to become managing this risk, a well water survey was more widespread with climate change. In Atlantic completed in the summer of 2015 in eastern Canada, the association between climate change Shelburne County. The objective of the survey was and saltwater intrusion has been discussed by the to provide baseline information on salt levels in Atlantic Climate Adaptation Solutions Association wells to help understand the current extent of (Prince Edward Island Department of Environment, saltwater intrusion since there are few sources of Labour and Justice, 2011) and case studies have existing well water chemistry data in this area of been completed in each of the four Atlantic the province. -

May 31 (Wolfville)

OPEN FUNDRAISING – EVENT REPORT May 31 (Wolfville) The Liberal Party of Canada has moved forward with the strongest standards in federal politics for more open and transparent party fundraising events, and is challenging other parties to do the same. The Liberal Party believes that fundraising events with Ministers, Party Leaders, and Leadership candidates as special guests should meet even stronger standards for transparency, including advance posting, hosting in publicly accessible spaces, timely reporting of event details and guests, and the facilitation of media coverage. The Liberal Party’s own independent steps were implemented in advance of legislation that has been proposed by the government. For more details, please visit: liberal.ca/openfundraising Date May 31 2018 Featured guest(s) Justin Trudeau Location Wolfville, NS Venue Lightfoot & Wolfville Vineyards Event type National Range of donation amounts required to attend $75-$400 ATTENDEES: Attendees for this event are listed below, with the exception of minors, members of the press, volunteers, or any support staff. Last Name First Name City Prov. Abu-Dayyeh Faris Halifax NS Almuhtaseb Nida Bedford NS Andrews Robert Halifax NS Anjoul Ray Halifax NS Arafeh Lina Halifax NS Armitstead Wayne Mahone Bay NS Attwater Alan Dartmouth NS Attwater Stephanie Dartmouth NS Bagley Andrew Canning NS Barrett Jeffrey Falmouth NS Bidgod Cheryl Bedford NS Bishop Darcy Black River NS Bizimana Telesphore Halifax NS Blain Dylan Dartmouth NS Blois Barron Kennetcook NS Blois Deborah Kennetcook NS Bramwell Robert Mahone Bay NS Brett Derek Bedford NS Brett Harper Bedford NS Brison Scott Newport NS Media questions? Please contact [email protected] Posted: 11/06/2018 1 Last Name First Name City Prov. -

Index to NGA Charts, Region 1

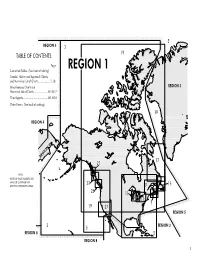

1 2 REGION 1 COASTAL CHARTS Stock Number Title Scale =1: 11004 Mississippi River to Rio Grande 866,500 14003 Cape Race to Cape Henry 1,532,210 14018 The Grand Banks of Newfoundland and the Adjacent Coast 1,200,000 14024 Island of Newfoundland 720,240 15017 Hudson Strait (OMEGA) 1,000,000 15018 Belle Isle to Resolution Island (OMEGA) 1,000,000 15020 Hudson Strait to Greenland 1,501,493 15023 Queen Elizabeth Islands - Southern Part and Adjacent Waters 1,000,000 16220 St. Lawrence Island to Bering Strait 315,350 17003 Strait of Juan de Fuca to Dixon Entrance 1,250,000 18000 Point Conception to Isla Cedros 950,000 19008 Hawaiian Islands (OMEGA-BATHYMETRIC CHART) 1,030,000 38029 Baffin Bay (OMEGA) 917,000 38032 Godthabsfjord to Qeqertarsuaq including Cumberland Peninsula 841,000 38280 Kennedy Channel-Kane Basin to Hall Basin 300,000 38300 Smith Sound and Kane Basin 300,000 38320 Inglefield Bredning &Approaches 300,000 96028 Poluostrov Kamchatka to Aleutian Islands including Komandorskiye Ostrova 1,329,300 96036 Bering Strait (OMEGA) 928,770 3 4 REGION 1 COASTAL CHARTS EAST AND WEST COASTS-UNITED STATES Stock Number Title Scale =1: 11461 Straits of Florida-Southern Portion 300,000 13264 Approaches to Bay of Fundy 300,000 17005 Vancouver Island 525,000 17008 Queen Charlotte Sound to Dixon Entrance 525,000 17480 Queen Charlotte Sound 365,100 18766 San Diego to Islas De Todos Santos (LORAN-C) 180,000 5 6 NOVA SCOTIA AREA Stock Number Title Scale =1: Stock Number Title Scale =1: 14061 Grand Manan (Bay of Fundy) 60,000 14136 Sydney Harbour 20,000 14081 Medway Harbour to Lockeport Harbour including Liverpool 80,000 Plans: A. -

A Public Transit Map of Nova Scotia

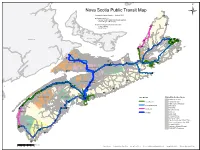

Nova Scotia Public Transit Map Compiled by Wayne Groszko - October, 2010 Dingwall Ü Base data courtesy of: - Service Nova Scotia and Municipal Relations - Halifax Regional Municipality Thanks to Dalhousie University GIS Centre Ingonish Cheticamp - Jennifer Strang - Curtis Syvret Englishtown PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND New Waterford Sydney Mines NEW BRUNSWICK North Sydney Dominion Inverness p£ Glace Bay Sydney Cape Breton Regionalp£ Handi-Trans Baddeck p£ Mabou Port Hood Whycocomagh p£ Louisbourg Amherst p£ Strait Area Transit p£Oxford St. Peter's Pictou p£ p£ Springhill p£ p£ L'Ardoise Cumberland County Transportation Association Antigonish Port Hawkesbury Trenton p£ p£ Westp£ville Isle Madame Stellarton C.H.A.D. Colchester County Transportation Society Parrsboro p£ Truro p£ p£Canso Sherbrooke Stewiacke East Hants Dial-a-Ride Kentville p£ p£Wolfville Shubenacadie Berwick Hantsport p£ Kings Paratransit p£ p£ Windsor Middleton Elmsdale p£ West Hants Dial-a-Ride Enfield Sheet Harbour Halifax Airport Bridgetown p£ Ship Harbour Annapolis Royal p£ p£ Bedford p£ p£ Trans County Transportation Society Chester Community Wheels Metro Transit Access-a-Bus Need a Lift Digby Dial-a-Ride Service Areas p£ Halifax Line Routes p£ p¤£ H.O.P.E (Yarmouth) p£ Chester p£ Local Transit Transport de Clare Trans County (Annapolis) Weymouth p£Mahone Bay p£ Long Distance Bus West Hants Bridgewater Lunenburg Church Point p£ p£ p£ p£ p£ East Hants Shuttle Van Kings Paratransit p£ Le Transport de Clare p£ Colchester p£ VIA Rail p£ Cumberland p£ C.H.A.D. (Pictou) p£ Strait Area Transit p£Liverpool Cape Breton Regional Handi-Trans Metro Transit Access-a-Bus HRM p£ HOPE Dial-a-Ride p£ Need-a-lift (HRM) p£ Proposed p£ p£Yarmouth Community Wheels (Chester) p£ p£ p£ PROPOSED (Shelburne) Shelburne p£ p£ p£ Lockeport p£ p£ p£ Clark's Harbour Kilometers 0 5 10 20 30 40 50 Project Partners: ---- Community Transit Nova Scotia ---- Ecology Action Centre ---- Service Nova Scotia and Municipal Relations ---- Transport Action Atlantic ---- Dalhousie University GIS Centre. -

Tire Remitters.Pdf

DIVERT NS TIRE MEMBERSHIP CHANGES Company Name Operating As Location Status Effective Date Comments Eye Deal Auto Eye Deal Auto Musquodoboit Harbour, NS De‐registered 5/31/2021 Tire Warehouse On‐Line Ltd. Trail Tire Group Edmonton, AB Registered 5/31/2021 3302269 NS Ltd. Frontline Trailers & Truck Stuff Dartmouth, NS De‐registered 4/30/2021 Tires on the Spot Inc. Tires on the Spot Inc. Dartmouth, NS De‐registered 4/30/2021 3344322 NS Ltd. Chuck's Auto & Glass Ltd. Coldbrook, NS Registered 4/30/2021 Eastern Powersports Ltd. Eastern Powersports Ltd. Amherst, NS Registered 4/30/2021 Meadowvale Ford Sales and Service Meadowvale Ford Sales and Service Mississauga, ON Registered 4/30/2021 William Gray Enterprises Ltd. OK Tire Lower Sackville, NS De‐registered 3/31/2021 Adventure Sports Ltd. Adventure Sports Ltd. Dartmouth, NS De‐registered 3/31/2021 Trailer Wizards Ltd. Trailer Wizards Ltd. Burnaby, BC De‐registered 3/31/2021 Kenneth Lutz Trucks Ltd. Kenneth Lutz Trucks Ltd. Aylesford, NS Registered 3/31/2021 Tireseasy LLC Tireseasy LLC Victoria, BC De‐registered 2/28/2021 Wal‐Mart Canada Wal‐Mart Canada Amherst, NS De‐registered 2/28/2021 Wal‐Mart Canada Wal‐Mart Canada New Minas, NS De‐registered 2/28/2021 Wal‐Mart Canada Wal‐Mart Canada Truro, NS De‐registered 2/28/2021 Wal‐Mart Canada Wal‐Mart Canada Halifax West, NS De‐registered 2/28/2021 Wal‐Mart Canada Wal‐Mart Canada Bedford, NS De‐registered 2/28/2021 Wal‐Mart Canada Wal‐Mart Canada New Glasgow, NS De‐registered 2/28/2021 Wal‐Mart Canada Wal‐Mart Canada Dartmouth, NS De‐registered 2/28/2021 Wal‐Mart Canada Wal‐Mart Canada Yarmouth, NS De‐registered 2/28/2021 Wal‐Mart Canada Wal‐Mart Canada Antigonish, NS De‐registered 2/28/2021 Wal‐Mart Canada Wal‐Mart Canada Bridgewater, NS De‐registered 2/28/2021 Lequille's Alignment Lequille's Alignment Annapolis Royal, NS Registered 2/28/2021 Provincial Spring Shop Provincial Spring Shop Halifax, NS Registered 2/28/2021 Big Boy Auto Big Boy Auto Dartmouth, NS Registered 1/31/2021 Midnight Tire Ltd. -

September October 2019 NS Lion

In This Issue Oldest Lion….……………..…....….....Pg. 1 Lions Club International In Memory…………..…...….………...Pg. 2 District N2 DG’s Newsletter…………...………..….Pg.3 Nova Scotia Canada FallCabinet………..…………Pgs.6&7 Highlight & Photo’s Pgs…..2,4,5,11,14&15 Points……………….………………Pgs8&9 Club Standing…..….……..…………..Pg.10 From Activity Reports…...….....Pgs. 12&13 THE NOVA SCOTIA LION June points…………….……….…….Pg.16 Vol. 52 No. 2 September/October 2019 Oldest Lion is 104 years young - DG Debbie pre- sented Jim Hanifen with "This Lion can still Roar at 104!" award at his home in Anti- gonish "In Memory of Deceased Lion's District N2" 2019 2020” Plunger Toss Baddeck: Lion Bill Smith tournament at Sheet Harbour: Musq. Harbour Lion Brian Smith for Terry Fox PDG Art Mac Kenzie Fundraiser. Chezzetcook: Lion Cyril Randall (Charter Member) Windsor: Lion Dave Burgess EP/CB: Lion Valerie Hawley Berwick: Lion John Leduc Sackville Lions Club Adopt-A- Highway along The Nova Scotia Lion Digby & Area Lions Club Regular Meeting 4th Wed. 6:30 with the local DISTRICT GOVERNOR Smith’s Cove Fire Hall Debbie McGinley 43 North Old Post Rd Army Cadet 17 Scott Lane KL Edward McCormick Milford, NS B0N 1Y0 902-467-4112 Squadron 902-758-1927(H) Sec. William McCormick 902-758-5166C) 902-467-3754 [email protected] Visitation: Lion Gerry 467-3671 LIONS FOUNDATION OF CANADA CABINET SECRETARY/TREASURER NOVA SCOTIA DIRECTOR Lawrencetown & Lion Dave Manning Scott MacKenzie 2250 Hwy #2 District Lions Club PO Box 102 Milford Station, NS B0N 1Y0 Musquodoboit Harbour, NS [email protected] B0J 2L0 1st Tuesday - Supper 902-758-3130 902-883-7018(C) 3rd Tuesday - Business 902-499-1922(H) Both 6:30 pm [email protected] Legion Hall (Side Entrance) EDITOR/ADVERTISMENT Secretary 902-824-3880 Lion Tracey Carocci DARTMOUTH LIONS CLUB 7856 Hwy 201 Baddeck Lions Club SPRYFIELD Meetings 1st & 3rd Tuesday at 6:30 pm Lawrencetown 1st Thursday LIONS CLUB Panda Buffet or ANA VETS Bldg.