Chimpanzee Signing: Darwinian Realities and Cartesian Delusions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sign Language Endangerment and Linguistic Diversity Ben Braithwaite

RESEARCH REPORT Sign language endangerment and linguistic diversity Ben Braithwaite University of the West Indies at St. Augustine It has become increasingly clear that current threats to global linguistic diversity are not re - stricted to the loss of spoken languages. Signed languages are vulnerable to familiar patterns of language shift and the global spread of a few influential languages. But the ecologies of signed languages are also affected by genetics, social attitudes toward deafness, educational and public health policies, and a widespread modality chauvinism that views spoken languages as inherently superior or more desirable. This research report reviews what is known about sign language vi - tality and endangerment globally, and considers the responses from communities, governments, and linguists. It is striking how little attention has been paid to sign language vitality, endangerment, and re - vitalization, even as research on signed languages has occupied an increasingly prominent posi - tion in linguistic theory. It is time for linguists from a broader range of backgrounds to consider the causes, consequences, and appropriate responses to current threats to sign language diversity. In doing so, we must articulate more clearly the value of this diversity to the field of linguistics and the responsibilities the field has toward preserving it.* Keywords : language endangerment, language vitality, language documentation, signed languages 1. Introduction. Concerns about sign language endangerment are not new. Almost immediately after the invention of film, the US National Association of the Deaf began producing films to capture American Sign Language (ASL), motivated by a fear within the deaf community that their language was endangered (Schuchman 2004). -

The 5 Parameters of ASL Before You Begin Sign Language Partner Activities, You Need to Learn the 5 Parameters of ASL

The 5 Parameters of ASL Before you begin Sign Language Partner activities, you need to learn the 5 Parameters of ASL. You will use these parameters to describe new vocabulary words you will learn with your partner while completing Language Partner activities. Read and learn about the 5 Parameters below. DEFINITION In American Sign Language (ASL), we use the 5 Parameters of ASL to describe how a sign behaves within the signer’s space. The parameters are handshape, palm orientation, movement, location, and expression/non-manual signals. All five parameters must be performed correctly to sign the word accurately. Go to https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FrkGrIiAoNE for a signed definition of the 5 Parameters of ASL. Don’t forget to turn the captions on if you are a beginning ASL student. Note: The signer’s space spans the width of your elbows when your hands are on your hips to the length four inches above your head to four inches below your belly button. Imagine a rectangle drawn around the top half of your body. TYPES OF HANDSHAPES Handshapes consist of the manual alphabet and other variations of handshapes. Refer to the picture below. TYPES OF ORIENTATIONS Orientation refers to which direction your palm is facing for a particular sign. The different directions are listed below. 1. Palm facing out 2. Palm facing in 3. Palm is horizontal 4. Palm faces left/right 5. Palm toward palm 6. Palm up/down TYPES OF MOVEMENT A sign can display different kinds of movement that are named below. 1. In a circle 2. -

Building BSL Signbank: the Lemma Dilemma Revisited

Fenlon, Jordan, Kearsy Cormier & Adam Schembri. in press. Building BSL SignBank: The lemma dilemma revisited. International Journal of Lexicography. (Pre-proof draft: March 2015. Check for updates before citing.) 1 Building BSL SignBank: The lemma dilemma revisited Abstract One key criterion when creating a representation of the lexicon of any language within a dictionary or lexical database is that it must be decided which groups of idiosyncratic and systematically modified variants together form a lexeme. Few researchers have, however, attempted to outline such principles as they might apply to sign languages. As a consequence, some sign language dictionaries and lexical databases appear to be mixed collections of phonetic, phonological, morphological, and lexical variants of lexical signs (e.g. Brien 1992) which have not addressed what may be termed as the lemma dilemma. In this paper, we outline the lemmatisation practices used in the creation of BSL SignBank (Fenlon et al. 2014a), a lexical database and dictionary of British Sign Language based on signs identified within the British Sign Language Corpus (http://www.bslcorpusproject.org). We argue that the principles outlined here should be considered in the creation of any sign language lexical database and ultimately any sign language dictionary and reference grammar. Keywords: lemma, lexeme, lemmatisation, sign language, dictionary, lexical database. 1 Introduction When one begins to document the lexicon of a language, it is necessary to establish what one considers to be a lexeme. Generally speaking, a lexeme can be defined as a unit that refers to a set of words in a language that bear a relation to one another in form and meaning. -

Chimpanzees Use of Sign Language

Chimpanzees’ Use of Sign Language* ROGER S. FOUTS & DEBORAH H. FOUTS Washoe was cross-fostered by humans.1 She was raised as if she were a deaf human child and so acquired the signs of American Sign Language. Her surrogate human family had been the only people she had really known. She had met other humans who occasionally visited and often seen unfamiliar people over the garden fence or going by in cars on the busy residential street that ran next to her home. She never had a pet but she had seen dogs at a distance and did not appear to like them. While on car journeys she would hang out of the window and bang on the car door if she saw one. Dogs were obviously not part of 'our group'; they were different and therefore not to be trusted. Cats fared no better. The occasional cat that might dare to use her back garden as a shortcut was summarily chased out. Bugs were not favourites either. They were to be avoided or, if that was impossible, quickly flicked away. Washoe had accepted the notion of human superiority very readily - almost too readily. Being superior has a very heady quality about it. When Washoe was five she left most of her human companions behind and moved to a primate institute in Oklahoma. The facility housed about twenty-five chimpanzees, and this was where Washoe was to meet her first chimpanzee: imagine never meeting a member of your own species until you were five. After a plane flight Washoe arrived in a sedated state at her new home. -

My Five Senses Unit Two: Table of Contents

Unit Two: My Five Senses Unit Two: Table of Contents My Five Senses I. Unit Snapshot ................................................................................................2 II. Introduction .................................................................................................. 4 Interdisciplinary Unit of Study III. Unit Framework ............................................................................................ 6 NYC DOE IV. Ideas for Learning Centers ............................................................................10 V. Foundational and Supporting Texts ............................................................. 27 VI. Inquiry and Critical Thinking Questions for Foundational Texts ...................29 VII. Sample Weekly Plan ..................................................................................... 32 VIII. Student Work Sample .................................................................................. 37 IX. Family Engagement .....................................................................................39 X. Supporting Resources ................................................................................. 40 XI. Foundational Learning Experiences: Lesson Plans .......................................42 XII. Appendices ...................................................................................................59 The enclosed curriculum units may be used for educational, non- profit purposes only. If you are not a Pre-K for All provider, send an email to [email protected] -

A Message from the President

Bulletin Toni Ziegler - Executive Secretary Volume 27, Number 1 March 2003 A Message from the President... “Now, when they come down to Canada Scarcely ‘bout half a year. .” Bob Dylan, “Canadee-i-o”, 1992 Annual Meeting in Calgary, August 2003 As usual, Dylan is right on the mark with his lyrics, since we are now fast approaching the 6-month mark to our annual meeting in Calgary, Alberta. By the time you receive this newsletter, abstracts will have been received and the scientific review will be underway by Marilyn Norconk and the rest of the program committee. This committee has already guaranteed a scientifically stimulating conference by arranging for invited presentations by Suzette Tardif, Linda Fedigan, Amy Vedder, and the receipient of the 2002 Distinguished Primatologist Award, Andy Hendrickx. The late meeting date (31 July – 2 August 2003) presumably allowed each of us to collect that last bit of crucial data needed for our abstracts! I look forward to hearing from all of you about the latest advances in primatology in disciplines ranging from anthropology to zoology, and having my students tell you about our recent research endeavors. ASP President Jeff French and Outstanding Poster Presentation winner Michael Rukstalis at the 2002 Oklahoma meetings World Politics and Primatology As I write these words in late February, the world faces an uncertain period where the risk of global instability is higher than at any other time in my 48-year lifetime. US and alllied troops are gathering around Iraq, North Korea is firing missiles into the Sea of Japan, and Pakistan and India are once again restless on their shared and disputed borders. -

Program and Abstracts

PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS SYMPOSIUM ON UNIVERSITY RESEARCH AND CREATIVE EXPRESSION 15TH ANNUAL CONFERENCE CENTRAL WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY ELLENSBURG, WASHINGTON MAY 20, 2010 STUDENT UNION AND RECREATION CENTER SPONSORED BY: Office of the President Office of the Provost Office of Graduate Studies and Research Office of Undergraduate Studies The Central Washington University Foundation College of Arts and Humanities College of Business College of Education and Professional Studies College of the Sciences James E. Brooks Library Student Affairs and Enrollment Management Len Thayer Small Grants Programs The Wildcat Shop CWU Dining Services The Copy Cat Shop The Educational Technology Center A SPECIAL THANKS TO OUR COMMUNITY SPONSORS: Kelley and Wayne Quirk – Major Supporter Deborah and Roger Fouts – Program Supporter Kirk and Cheri Johnson – Program Supporter Anthony Sowards – Program Supporter Associated Earth Sciences – Morning Reception Sponsor GeoEngineers – Morning Poster Session Sponsor Valley Vision Associates – Program Supporter SOURCE is partially funded by student activities fees. 1 CONTENTS History and Goals of the Symposium ................................................................................4 Student Fashion Show ......................................................................................................4 Student Art Show ...............................................................................................................5 Big Brass Blowout .............................................................................................................5 -

Guideline for Working with Students Who Are Deaf and Hard of Hearing

Guidelines for Working with Students Who Are Deaf and Hard of Hearing in Virginia Public Schools The Virginia Department of Education Department of Special Education and Student Services with The Partnership for People with Disabilities Virginia Commonwealth University Revised September 2019 Copyright © 2019 This document can be reproduced and distributed for educational purposes. No commercial use of this document is permitted. Contact the Virginia Department of Education, Department of Special Education and Student Services prior to adapting or modifying this document for non-commercial purposes. This document can be found at the Virginia Department of Education (VDOE) website. Type the title in the “Search” box. The Virginia Department of Education does not discriminate on the basis of race, sex, color, national origin, religion, sexual orientation, age political affiliation, veteran status, or against otherwise qualified persons with disabilities in its programs and activities. TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................ ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................... vi KEY TO ACRONYMS USED IN THIS DOCUMENT ......................................................... viii INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 1 Law and Regulations .............................................................................................................. -

BILINGUAL ENGLISH and AUSLAN DEVELOPMENT SCALE Name Of

BILINGUAL ENGLISH AND AUSLAN DEVELOPMENT SCALE Name of child:_______________________________________ E: Emerging C: Consolidated Age English E C Auslan E C Pragmatic Language Skills E C 0;0- Pre-intentional Pre-intentional 0;3 . responds to familiar . coos . manual movements touch, voices, faces . vocal play . moves arms/legs to communicate . smiles . cries, smiles, to express needs . cries, smiles, to express needs . quietens and looks intently . turns towards the speaker . turns towards signer at familiar voices/faces 0;3- Intentional Intentional . smiles, takes turns, attends 0;6 to faces . vocalizes to stimuli . starts to copy signs, gestures . laughs to express pleasure . says 'm'; makes mouth movements . uses facial expressions to when talked to communicate . cries at angry voices and faces . syllable-like vocal play, with long . manual movements show vowels emergence of rhythm . maintains eye contact . uses voice to make contact with . uses gestures to attract and . puts arms up to be lifted people and to keep their attention maintain attention, request, refuse, reject . copies facial expressions; . starts to respond to name reaches towards objects © Levesque 2008 Age English E C Auslan E C Pragmatic Language Skills E C 0;6- . canonical (‘reduplicated’) babbling, . manually babbles, using rhythmic . likes attention 0;9 eg. ‘baba’, ‘gaga’ hand movements, eg. repeated opening & closing, tapping . plays Peek-a-boo . vocalizes for attention . uses hand movements for attention . points to request . uses voice to join in with familiar . uses gestures to join in with rhyme/game familiar rhyme/game . uses two gestures or gesture and vocalization . recognizes and responds to own . responds to visual and tactile to: attract attention, ask name attention-gaining strategies for things, refuse . -

Environmental Crime- the Globe's Second Largest Illegal Enterprise?

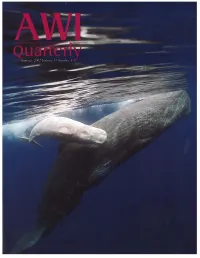

ABOUT THE COVER Sighted off the Azores in the North Atlantic, an extremely rare 13-foot-long white sperm whale calf swims with his mother. Sperm whales are the largest toothed whales- adult males can be fifty feet long and weigh forty tons. Pho tographer Flip Nicklin could not determine whether this real-life baby "Moby Dick's" eyes were pink, but the calf appears to be a pure albino. Despite his dolphin smile he's in grave danger from his mother's milk, which may be contaminated by absorbed chemicals, heavy metals, and other noxious sub stances, as a result of ocean pollution. Other threats come from ship strikes, being caught in entangling fishing nets, and whaling. The Japanese kill sperm whales today under the guise of "scientific research," but whale meat and oil end up for sale in Japan. In May 2002, Japan hosted a remarkably conten tious meeting ofthe International Whaling Commission, established in 1946 to regulate commercial whaling. (See story pages 4-5.) DIRECTORS Marjorie Cooke Roger Fouts, Ph.D. David 0. Hill Fredrick Hutchison Take a Bite Out of the Toothfish Trade Cathy Liss Christine Stevens Cynthia Wilson ince AWl first reported on the serious conservation implications of the Sinternational trade in Patagonian Toothfish last winter, a concerted OFFICERS global effort has taken hold to curtail the commercialization of this fish, Christine Stevens, President often marketed under the name, "Chilean Sea Bass." Cynthia Wilson, Vice President It is estimated that overfishing and illegal catches could push the Fredrick Hutchison, CPA, Treasurer Patagonian toothfish to extinction in five years. -

A Path to Democratic Renewal"

PN-ABK-494 Best available copy -- portions of annexes are illegible PA -1\LK* A-+ National Democratic Institute National Republican Institute for International Affairs for International Affairs "A PATH TO DEMOCRATIC RENEWAL" A REPORT ON THE FEBRUARY 7, 1986 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION IN THE PHILIPPINES By the INTERNATIONAL OBSERVER DELEGATION Based on a January 26 to February 19, '.986 observer mission to the Philippines by forty-four delegates from nineteen countries National Democratic Institute National Republican Institute for International Affairs for International Affairs 1717 Massachusetts Ave., N.W., Suite 605 001 Indiana Avenue, N.W., Suite 615 Washington, D.C. 20036 Washington. DC. 2000-1 (202) 328-3136 Telex 5106015068NDIIA (202) 783-2280 Te'ex 510',00016INRIIA Politicaldevelopment institutes workingfordemocracy DELEGATION MEMBERS J. Brian Atwood, USA Jerry Austin, USA Manuel Ayau, Guatemala Elizabeth Bagley, USA Smith Bagley, USA Ercol Barrow, Barbados Tabib Bensoda, the Gambia Mark Braden, USA John Carbaugh, USA Glenn Cowan, USA Curtis Cutter, USA Rick Fisher, USA Larry Garber, USA Raymond Gastil, USA Antonio Gomes de Pinho, Portuga B.A. Graham, Canada Guillermo Guevara, El Salvador Robert Henderson, USA Robert Hill, Australia John Hume, Northern Ireland Patricia Keefer, USA Martin Laseter, USA Dorothy Lightborne, Jamaica John Loulis, Greece Lord George Mackie, Scotland-UK Judy Norcross, USA Patrick O'Malley, Ireland Juan Carlos Pastrana, Colombia Misael Pastrana, Colombia Howard Penniman, USA Jose Rodriguez Iturbe, Venezuela Peter Schram, USA Keith Schuette, USA Ronald Sebego, Botswana Elaine Shocas, USA David Steinberg, USA Bill Sweeney, USA Dennis Teti, USA William Tucker, USA Steven Wagner, USA Kathleena Walther, USA Edward Weidenfeld, USA Curt Wiley, USA Sue Wood, New Zealand ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The sponsors wish to thank each of the memters of the delegation for their participation in this historic mission. -

When the Apes Speak, Linguists Listen. Part 1. the Ape Language Studies

Current Comments” EUGENE GARFIELD INSTITUTE FOR SCIENTIFIC INFORMATION* 3501 MARKET ST PHILADELPHIA, PA 19104 When the Apes Speak, Linguists Lfsten. Part 1. The Ape Language Studies Number 31 August 5, 1985 “Come open, “ “Hurry drink milk,” Tokyo, noted that apes do not lack the “You chase me,” and “Please machine intelligence needed for language. Rath- give milk” are all parts of conversations er, the most significant difference is be- between humans and apes. Since the late tween the human and chimpanzee vocal 1960s psychologists and anthropologists tracts.z Philip Lieberman, Department have launched intensive projects to of Linguistics, Brown University, Provi- teach great apes—such as the chimpan- dence, Rhode Island, reported differ- zee, gorilla, and orangutan—a form of ences in the structure of the oral cavity communication that is comparable to and less tongue mobility in chimpanzees human language. The apes are large tail- compared to humans. s In the chimpan- less primates that are classified just be- zee, the tongue is longer and narrower low humans in the evolutionary tree. Re- than the human tongue. The placement search on “animal linguistics” and the of the chimpanzee’s tongue and its ma- different approaches to it have resulted neuverability within the oral cavity pre- in debate among the ape language re- vent the chimpanzee from producing the searchers and among linguists as to the full range of vowel sounds necessary for definition and uniqueness of human lan- human speech, guage. This first part of a twopart essay Of the early efforts to teach spoken focuses on the ape language projects.