Local Actions of National and Regional Impact

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Object-Initial Languages1

OBJECT-INITIAL LANGUAGES1 DESMOND C. DERBYSHIRE AND GEOFFREY K. PULLUM UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON 0. Introduction evidence. The existence of languages hav- 1. OVS languages ing a basic order in which the direct object 1.1. Hixkaryana NP is initial has been widely denied in the 1.2. Apalai literature of syntactic typology. For ex- 1.3. Makushi ample, Venneman (1973:27) states: 1.4. Hianacoto-Umaua "Greenberg observes that of the six pos- 1.5. Arekuna-Taulipang sible arrangements (SVO, SOV, VSO, 1.6. Panare VOS, OSV and OVS) only three occur as 1.7. Bacairi the only or dominant pattern of declarative 1.8. Asurini clauses, viz. those in which S precedes 0: 2. OSV languages VSO, SVO and SOV (universal 1). This is 2.1. Apurina readily explained." Venneman's reference 2.2. Urubu slightly misrepresents Greenberg, who in 2.3. Nadeb fact said (1963:61): "Logically there are six 2.4. Xavante possible orders: SVO, SOV, VSO, VOS, 3. Conclusions and prospects OSV and OVS. Of these six, however, only three normally occur as dominant 0. Most languages, perhaps all, clearlyorders. The three which do not occur at have what can be called a "basic order" of all, or at least are excessively rare, are sentence constituents. This is the order VOS, OSV, and OVS." Greenberg's quali- most typically found in simple declarative fications are rather important; Venneman transitive clauses where no stylistic (1973)or has silently elevated Greenberg's discourse-conditioned permutation is hedged in claim into an absolute one. Pullum (1977) makes a more explicit attempt to extract a lawlike universal from I Some of the many people to whom we owe thanks for the help they have given us are mentioned Greenberg's statistical claim. -

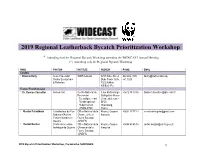

2019 Regional Leatherback Bycatch Prioritization Workshop

2019 Regional Leatherback Bycatch Prioritization Workshop * Attending both the Regional Bycatch Workshop attending the WIDECAST Annual Meeting (*) Attending only the Regional Bycatch Workshop NAME POSITION INSTITUTE ADDRESS PHONE EMAIL Canada: * Brianne Kelly Senior Specialist WWF-Canada 5251 Duke Street 902.482.1105 [email protected] Marine Ecosystems Duke Tower Suite ext. 3025 & Fisheries 1202 Halifax NS B3J 1P3 France/ French-Guiane * Dr. Damien Chevallier Researcher Centre National de 3 rue Michel-Ange +0612 97 10 54 [email protected] Recherche Délégation Alsace Scientifique – Inst 23 rue du Loess – Pluridisciplinaire BP20 Hubert Curien Strasbourg, (CNRS-IPHC) France * Nicolas Paranthoën Coordinateur du Plan Office National de la Kourou, Guyane +0694 13 77 44 [email protected] National d'Actions Chasse et de la française Tortues Marines en Faune Sauvage Guyane (ONCFS) * Rachel Berzins Cheffe de la cellule Office National de la Kourou, Guyane +0694 40 45 14 [email protected] technique de Guyane Chasse et de la française Faune Sauvage (ONCFS) 2019 Bycatch Prioritization Workshop, Paramaribo SURINAME 1 * Christelle Guyon Chargée de mission Direction de Rue Carlos +0594 29 68 60 Christelle.guyon@developpement- biodiversité marine l’Environnement, de Fineley CS 76003, durable.gouv.fr l’Aménagement et 97306 Cayenne du Logement Guyane française de Guyane * Nolwenn Cozannet Chargée du projet WWF France, 2, rue Gustave +0594 31 38 28 [email protected] Dauphin de Guyane bureau Guyane Charlery 97 300 CAYENNE -

Object Initial Languages Desmond C

Work Papers of the Summer Institute of Linguistics, University of North Dakota Session Volume 23 Article 2 1979 Object initial languages Desmond C. Derbyshire SIL-UND Geoffrey K. Pullam SIL-UND Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/sil-work-papers Recommended Citation Derbyshire, Desmond C. and Pullam, Geoffrey K. (1979) "Object initial languages," Work Papers of the Summer Institute of Linguistics, University of North Dakota Session: Vol. 23 , Article 2. DOI: 10.31356/silwp.vol23.02 Available at: https://commons.und.edu/sil-work-papers/vol23/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Work Papers of the Summer Institute of Linguistics, University of North Dakota Session by an authorized editor of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OBJECT INITIAL LANGUAGES Desmond C. Derbyshire Geoffrey K. Pullum University College London 0. Introduction l. OVS languages l. l Hf xkaryana 1.2 Apalaf (Aparaf) 1.3 Makushi (MakGsi, Makaxi, Makuchf) l .4 Hfanacoto-Umaua l .5 Arekuna/Taulfpang 1.6 Panare l. 7 Bacair1 l .8 Asurfn1 2. OSV languages 2.1 Apurina 2 .2 Uruba 2.3 Nad@b 2.4 Xavante 3. Conclusions and prospects O. Most languages, and perhaps all, clearly ha.ve what can be called a basic order of sentence constituents. This will be the order most typically found in simple declarative transitive clauses where no stylistic or discourse-conditioned permutation is fn evidence. The existence of languages having a basic order in transitive clauses fn which the direct object NP is initial has been regularly and widely denied in the literature of syntactic typology. -

Special Update on Quito Process V Technical Meeting on Human

Special update on Quito Process AS OF NOVEMBER 2019 LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN AS OF NOVEMBER 2019 LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN V Technical Meeting on HumanV EMobilityNEZUVELEANNEZUE LofAN Venezuelan Citizens in the RegionREFUGEERSE F&U MGIEGERSA &N TMSIG INR ATNHTES R IENG TIOHNE REGION UNITED STATES UNITED STATES BOGOTA, COLOMBIA Havana\ MEXICO Havana\ MEXICO CUBA DOMINICAN 14-15 NOVEMBER 2019 CUBA DOMINICAN \ REPUBLIC Mexico \ HAITI \ PUERTO REPUBLIC Mexico JAMAICA \ Santo HAITI \ PUERTO City \BELIZE JAMAICA \ RICO City \ Domingo Santo RICO BELIZE Domingo \ HONDURAS CARIBBEAN SEA GUATEMALA \ \ HONDURAS CARIBBEAN SEA \ GUATEMALA \ EL SALVADOR NICARAGUA \ ARUBA CURACAO \ EL SALVADOR APoRrUt BA \NICARAGUA Spain CURACAO Port San José \ \ TRINIDAD Spain \ Panamá San JoséCaracas & TOBA\GO \ TRINIDAD PARTICIPATION COSTA \ \ Caracas Panamá & TOBAGO COSTA \ RICA PANAMA Georgetown RICA PANAMAVENEZUELA \ Georgetown VENEZ\UPaErLaAmaribo \ GUYANA Paramaribo \Bogotá \ CGayUeYnAneNA \ \Bogotá \ Cayenne COLOMBIA SURINAME COLOMBIA FRENCH SURINAME GUYANA FRENCH The fifth round of the Quito Process (Quito V – GUYANA \Quito \Quito ECUADOR Bogota Chapter) took place on 14-15 November ECUADOR (2019), with the participation of 12 States from PERU Latin America and the Caribbean, along with PERU \Lima BRAZIL key cooperating States, international financial \Lima BRAZIL \ BOLIVIA Brasilia \ BOLIVIA Brasilia institutions and other actors. \ \ Sucre Sucre PACIFIC PARAGUAY ATLANTIC PACIFIC PARAGUAY ATLANTIC OCEAN Asunción \ OCEAN The meeting follows up on four previous meetings OCEAN Asunción \ OCEAN QUITO V DECLARATION in September and November 2018, April and July QUITO V DECLARATION SIGNATORIES ARGENTINA SIGNATORIES ARGENTINA 2019, as part of a government-led initiative thatArge ntina \ URUGUAY Argentina \ URUGUAY Santiago \ \ Santiago \ Brazil Buenos Montevideo \ aims to harmonize the policies and practices of Brazil Aires Buenos Montevideo Chile CHILE Aires Chile CHILE the countries in the region. -

Annex to Press Release 253/20

Annex to Press Release 253/20 Annex to Press Release 253/20 on the 177th Period of Sessions 1. Gender-based violence and human rights for women in Cuba The organizations who requested the hearing said that gender-based violence is systematic in Cuba. These organizations highlighted pervasive domestic, institutional, and obstetric violence. They warned that this type of violence has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. Independent journalists and civil society organizations have recorded 19 femicides since the beginning of the pandemic. The IACHR noted that the State of Cuba’s democratic weakness contributes to a lack of legislative and administrative mechanisms to respond to violence. The Commission said that the report Situation of Human Rights in Cuba, published in 2020, provides evidence of these problems and makes specific recommendations to the Cuban State, in line with the applicable inter-American standards. 2. Human rights situation of lesbian and transgender women in the Americas The organizations who requested the hearing highlighted the challenges concerning the human rights of lesbian, bisexual, and transgender (LBT) women in the region (including violations of their rights in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, which featured increases in domestic violence, sexual violence, and the number of femicides). These organizations say that violations of the rights of LBT women are based on heteropatriarchal, binary conceptions of gender that are fueled by stereotypes and prejudice and lead to the justification and naturalization of violence in the media and other institutions. These organizations stressed that measures adopted to contain the pandemic which stipulated specific days when men and women could be on the streets led to many instances of discrimination and police violence against transgender and gender-diverse individuals. -

A Rapid Biological Assessment of the Upper Palumeu River Watershed (Grensgebergte and Kasikasima) of Southeastern Suriname

Rapid Assessment Program A Rapid Biological Assessment of the Upper Palumeu River Watershed (Grensgebergte and Kasikasima) of Southeastern Suriname Editors: Leeanne E. Alonso and Trond H. Larsen 67 CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL - SURINAME CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL GLOBAL WILDLIFE CONSERVATION ANTON DE KOM UNIVERSITY OF SURINAME THE SURINAME FOREST SERVICE (LBB) NATURE CONSERVATION DIVISION (NB) FOUNDATION FOR FOREST MANAGEMENT AND PRODUCTION CONTROL (SBB) SURINAME CONSERVATION FOUNDATION THE HARBERS FAMILY FOUNDATION Rapid Assessment Program A Rapid Biological Assessment of the Upper Palumeu River Watershed RAP (Grensgebergte and Kasikasima) of Southeastern Suriname Bulletin of Biological Assessment 67 Editors: Leeanne E. Alonso and Trond H. Larsen CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL - SURINAME CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL GLOBAL WILDLIFE CONSERVATION ANTON DE KOM UNIVERSITY OF SURINAME THE SURINAME FOREST SERVICE (LBB) NATURE CONSERVATION DIVISION (NB) FOUNDATION FOR FOREST MANAGEMENT AND PRODUCTION CONTROL (SBB) SURINAME CONSERVATION FOUNDATION THE HARBERS FAMILY FOUNDATION The RAP Bulletin of Biological Assessment is published by: Conservation International 2011 Crystal Drive, Suite 500 Arlington, VA USA 22202 Tel : +1 703-341-2400 www.conservation.org Cover photos: The RAP team surveyed the Grensgebergte Mountains and Upper Palumeu Watershed, as well as the Middle Palumeu River and Kasikasima Mountains visible here. Freshwater resources originating here are vital for all of Suriname. (T. Larsen) Glass frogs (Hyalinobatrachium cf. taylori) lay their -

The Story of *Ô in the Cariban Family1, °

Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 2 (May 2010): Fieldwork and Linguistic Analysis in Indigenous Languages of the Americas, ed. by Andrea L. Berez, Jean Mulder, and Daisy Rosenblum, pp. 91-123 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/ 5 http://hdl.handle.net/10125/4452 The Story of *ô in the Cariban Family1, ° Spike Gildeaa, B. J. Hoffb, and Sérgio Meirac aUniversity of Oregon bLeiden University cKoninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen/Leiden University This paper argues for the reconstruction of an unrounded mid central/back vowel *ô to Proto-Cariban. Recent comparative studies of the Cariban family encounter a consistent correspondence of ə : o : ɨ : e, tentatively reconstructed as *o2 (considering only pronouns; Meira 2002) and *ô (considering only seven languages; Meira & Franchetto 2005). The first empirical contribution of this paper is to expand the comparative database to twenty- one modern and two extinct Cariban languages, where the robustness of the correspond- ence is confirmed. In ten languages, *ô merges with another vowel, either *o or *ɨ. The second empirical contribution of this paper is to more closely analyze one apparent case of attested change from *ô > o, as seen in cognate forms from Island Carib and dialectal variation in Kari’nja (Carib of Surinam). Kari’nja words borrowed into Island Carib/Garí- funa show a split between rounded and unrounded back vowels: rounded back vowels are reflexes of *o and *u, unrounded back vowels reflexes of *ô and *ɨ. Our analysis of Island Carib phonology was originally developed by Douglas Taylor in the 1960s, supplemented with unpublished Garifuna data collected by Taylor in the 1950s. -

International Currency Codes

Country Capital Currency Name Code Afghanistan Kabul Afghanistan Afghani AFN Albania Tirana Albanian Lek ALL Algeria Algiers Algerian Dinar DZD American Samoa Pago Pago US Dollar USD Andorra Andorra Euro EUR Angola Luanda Angolan Kwanza AOA Anguilla The Valley East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antarctica None East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda St. Johns East Caribbean Dollar XCD Argentina Buenos Aires Argentine Peso ARS Armenia Yerevan Armenian Dram AMD Aruba Oranjestad Aruban Guilder AWG Australia Canberra Australian Dollar AUD Austria Vienna Euro EUR Azerbaijan Baku Azerbaijan New Manat AZN Bahamas Nassau Bahamian Dollar BSD Bahrain Al-Manamah Bahraini Dinar BHD Bangladesh Dhaka Bangladeshi Taka BDT Barbados Bridgetown Barbados Dollar BBD Belarus Minsk Belarussian Ruble BYR Belgium Brussels Euro EUR Belize Belmopan Belize Dollar BZD Benin Porto-Novo CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Bermuda Hamilton Bermudian Dollar BMD Bhutan Thimphu Bhutan Ngultrum BTN Bolivia La Paz Boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Sarajevo Marka BAM Botswana Gaborone Botswana Pula BWP Bouvet Island None Norwegian Krone NOK Brazil Brasilia Brazilian Real BRL British Indian Ocean Territory None US Dollar USD Bandar Seri Brunei Darussalam Begawan Brunei Dollar BND Bulgaria Sofia Bulgarian Lev BGN Burkina Faso Ouagadougou CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Burundi Bujumbura Burundi Franc BIF Cambodia Phnom Penh Kampuchean Riel KHR Cameroon Yaounde CFA Franc BEAC XAF Canada Ottawa Canadian Dollar CAD Cape Verde Praia Cape Verde Escudo CVE Cayman Islands Georgetown Cayman Islands Dollar KYD _____________________________________________________________________________________________ -

Science Snap (#26): Angel Falls, Venezuela

Science Snap (#26): Angel Falls, Venezuela Sorcha McMahon is a third year PhD student in the School of Earth Sciences at the University of Bristol. Sorcha is investigating how strange igneous rocks called carbonatites may have formed, using both natural samples and high-pressure experiments. Canaima National Park. Photo credit: Sorcha McMahon Angel Falls is the world’s highest uninterrupted waterfall in the Canaima National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage site in the Gran Sabana region of Bolívar State, in Venezuela. The waterfall drops from the summit of the largest tepui (table-top mountain) of the Guiana Highlands of South America, Auyantepui, from a height of 979 m. Angel Falls is said to have inspired the setting of the Disney animated film Up(2009) where the location is called Paradise Falls. The nearby Mount Roraima inspired the Scottish author Arthur Conan Doyle to write his novel The Lost World about the discovery of a living prehistoric world full of dinosaurs and primeval plants. The borders of Venezuela, Brazil, and Guyana meet on the top of this tepui, which translates to “house of the gods” in the native tongue of the Pemon, the indigenous people who inhabit the Gran Sabana. Tepuis host a unique array of endemic plant and animal species, with ~1/3 of the plants found nowhere else on the planet. Angel Falls, Venezuela. It is also known as “Kerepakupai Vená” in the original indigenous Pemon language, meaning “waterfall of the deepest place”. Photo credit: Sorcha McMahon The extraordinary topography is part of the Guiana Shield, and began as the Great Plains; an igneous-metamorphic basement formed during the Precambrian as part of the supercontinent Gondwanaland (approx. -

Venezuela: Health Emergency

12-month update Venezuela: Health Emergency Emergency appeal no° MDRVE004 Timeframe covered by this update: 27 January 2019 to 27 April 2020 Date of issue: 23 May 2020 Operation timeframe: 18 months Operation start date: 27 January 2019 (DREF Operation End date: 27 July 2021 (Extended 12 operation) with Emergency Appeal start date: 8 April months with this update) 2019 Overall operation budget: 50 million Swiss francs DREF amount allocated: 1 million Swiss francs N° of people being assisted: 650,000 people Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners currently actively involved in the operation: The Venezuelan Red Cross (VRC) has approximately 4,000 volunteers, 24 branches and 11 subcommittees. In addition, it has 8 hospitals, 34 outpatient clinics and approximately 1,400 employees. Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), Pan American Health Organization (PAHO/WHO), Ministry of People's Power for Health (MPPS) and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Summary of major revisions This 12-month update reports on the integrated actions that the Venezuelan Red Cross, with IFRC support, has implemented during the first year of the operation. This operation has been closely linked to complement programmatic actions in Venezuela. During this reporting period, the coordinated efforts of VRC volunteers and staff with the IFRC team in country and through the Americas Regional Office have reached 164,606 people with health services; 81,005 people with water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) actions. The VRC has mobilized 3,617 volunteers and staff to contribute to the operation’s objectives, as well as receive training and other support to enhance their actions and ensure their safety. -

International Civil Aviation Organization SAM/IG/24-WP/5.2 South American Regional Office 10/23/2019 Twenty-Fourth Workshop/Meet

International Civil Aviation Organization SAM/IG/24-WP/5.2 South American Regional Office 10/23/2019 Twenty-Fourth Workshop/Meeting of the SAM Implementation Group (SAM/IG/24) - Regional Project RLA/06/901 (Lima, Peru, 04 to 08 November 2019) Agenda Item 4: Assessment of operational requirements to determine the implementation of improvements in communication, navigation and surveillance (CNS) capabilities for operations in route and terminal area FOLLOW UP TO THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE AMHS INTERCONNECTION (Presented by the Secretariat) SUMMARY This working paper presents information on the activities carried out since the SAM/IG/23 meeting for the implementation of the AMHS interconnection. References: - Twenty-Third Workshop/Meeting of the SAM Implementation Group (SAM/IG/23) Lima, Peru, 20-24 May 2019. - Final report of the Thirteenth Coordination Meeting of Project RLA/06/901 (RCC/13) (Lima, Peru, 27-28 June 2019). A – Safety ICAO strategic objectives: B – Air navigation capacity and efficiency 1 Background 1.1 The implementation of the AMHS interconnection is one of the air navigation implementation priorities contemplated in the Declaration of Bogotá for the period 2014-2016. Consideration has been given to the implementation of 27 interconnections. All AMHS interconnections required for the SAM Region are listed in Table CNS II-1, Volume II, of the CAR/SAM Regional Air Navigation Plan (Doc 8733 eANP). 1.2 The status of implementation of all AMHS interconnections of the SAM Region and their operational implementation date are shown in Appendix A to this working paper. 2 Discussion 2.1 The progress reported and the actions foreseen for the implementation of the AMHS interconnection in each SAM State are shown below. -

Venezuelans in Colombia

VENEZUELANS IN COLOMBIA - 1 - - 2 - VENEZUELANS IN COLOMBIA VENEZUELANS IN COLOMBIA: understanding the implications of the migrants crisis in Maicao (La Guajira) By Jair Eduardo Restrepo Pineda and Juliana Jaramillo Jaramillo Under the direction of: Manuela Torres Regional Director for Latin America and the Caribbean, Sayara International 2018 - 3 - Venezuelan migrant child takes refuge in the municipal Catholic Church facilities. Maicao, La Guajira, Colombia, October,2018. - 4 - VENEZUELANS IN COLOMBIA Acknowledgements Sayara International thanks the academic, research and administrative team of Corporación Universitaria Minuto de Dios (UNIMINUTO) for its effort and collaboration to carry out the study. More specifically, the authors, Juliana Jaramillo and Jair Eduardo Restrepo for their rigorous work in the methodology design and information analysis, as well as Armando Rhenals Coronado, Danys Alberth Aguirre Ocampo, for participation in data collection in the field. Sayara also thanks the migration expert Gisela P. Zapata for her role in ensuring data and analysis quality control of this final report. Likewise, Sayara also would like to thank the Venezuelan migrants and refugees that agreed to share their stories for the aim of this research. We’re also appreciative to Maicao’s local community, representatives of the local government and non-governmental organization for facilitating access to key information which contributed to the development of a comprehensive analysis of the local community and how its coping with the influx of migrants and refugees. Finally, Sayara thanks Exovera and its management and technical team, for its collaboration on the South American media monitoring, by providing access to their artificial intelligence platform as well as the 30 days of detailed media monitoring analysis.