George Wallace and His Circle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to the Papers of Wayne Greenhaw Archives & Special Collections

AUM Library Guide to the Papers of Wayne Greenhaw Archives & Special Collections Guide to the Papers of Wayne Greenhaw Auburn University at Montgomery Library Archives and Special Collections © AUM Library Written By: Rickey Best & Jason Kneip Last Updated: 6/24/2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS Content Page # Collection Summary 2 Administrative Information 3 Restrictions 3 Index Terms 3-4 Biographical Information 4-5 Scope and Content Note 5-6 1 of 21 AUM Library Guide to the Papers of Wayne Greenhaw Archives & Special Collections Arrangement 6-15 Inventory 15-20 Collection Summary Creator: H. Wayne Greenhaw Title: Wayne Greenhaw Papers Dates: 1940-2003 Quantity: 10 boxes; 12 linear feet Identification: 87/3 Contact Information: AUM Library Archives & Special Collections P.O. Box 244023 Montgomery, AL 36124-4023 Ph: (334) 244-3213 Email: [email protected] Administrative Information Preferred Citation: Wayne Greenhaw Papers, Auburn University at Montgomery Library, Archives & Special Collections. Acquisition Information: The Wayne Greenhaw collection was originally given to the library June 24, 1971. Additional accessions were given: April 17, 1990; June 1, 1995; March 15, 1996; April 27, 2005. Processing By: Rickey D. Best, Archivist/Special Collections Librarian (1996); Tracy Marie Lee, Student Assistant (1996); Jason Kneip, Archivist/Special Collections Librarian (2005); Jimmy Kanz, Student Assistant (2005). Processing Note: The materials have been processed as a living collection, meaning that new accessions are physically and intellectually kept separate from the 2 of 21 AUM Library Guide to the Papers of Wayne Greenhaw Archives & Special Collections initial donation. Series titles have been kept consistent with the initial donation where possible. -

The Daily Egyptian, May 19, 1972

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC May 1972 Daily Egyptian 1972 5-19-1972 The aiD ly Egyptian, May 19, 1972 Daily Egyptian Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/de_May1972 Volume 53, Issue 148 Recommended Citation , . "The aiD ly Egyptian, May 19, 1972." (May 1972). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Daily Egyptian 1972 at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in May 1972 by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Feminist talk thr ills g ir Is, chills guys By he MOIeJa Dally EIYJIdu Sa.ff Writer Anselma Dell'Olio. Convocation guest speaker, delivered a talk Thursday on the feminist movement which appeared to win the approval rI the female mem bers rI the audience, but seemed to up set the male members. Throughout the speech when there was clapping, it was, by and large, done by women. After the program: a disgruntled man was overheard sayIng, "Talk about sexist, she sure was. I don't see how women can be taken in by that bunk." Another male student responded with, "I'm a man and there's only so much I can take." But what exactly did Ms. Dell'Olio say to divide an audience so distinctly? She began by discussing the miscon ceptions rI the women's movement. "A • Girl '(llk common question among those against the movement is why should women want more liberation?" she observed, Anselma DeIrOlio (above) delivered a talk sarcastically. Ms. Dell'Olio said she on the feminist movement to the Con calls this the "Lady MacBeth theorv." vocation audience Thursday. -

Library Horizons Newletter Spring 12

~ LIBRARY HORIZONS A Newsletter of The University of Alabama Libraries SPRING 2012, VOL. 27, NO. 1 Brockmann Diaries Make Wonderful Addition to Special Collections UA Libraries has acquired the diaries of Charles Raven Brockmann, advertising manager for the H.W. Wilson publishing company for much of the Great Depression and later the long-time assistant director of the Mecklenburg County Public Library, headquartered in Charlotte, NC. Brockmann (1889-1970) was a committed diarist from his youth until just days before his death. With only a few gaps, the diaries chronicle his daily life through the greater part of the twentieth centur y. The diaries, acquired for UA Libraries by Dean Louis Pitschmann, will be kept in Hoole Special Collections Library. Te Brockmann Diaries came to the attention of Dean Pitschmann through an ongoing research project being otherwise examine them. Brockmann visited Miss Mary Titcomb, Librarian, conducted by Dr. Jeff Weddle, an helped design the truck, deemed “Te Washington County Free Library and associate professor in UA’s School Bookmobile,” though that term was not examined an original photograph of the of Library and Information Studies. yet in vogue, and served as its captain frst book wagon to be used in county Weddle is researching an H.W. Wilson during the frst year of its long trek. Te library service in this country, a horse outreach program, begun in 1929 for diaries provide insight into the day-to- drawn vehicle of unique design.” – May the purpose of sending a specially day business of Brockmann’s year on the 18, 1929 designed truck, laden with Wilson road and ofer an intimate account of the publications, on an epic, three-year middle-class life of this librarian, family Under the direction of Miss Mary Titcomb, tour of the United States. -

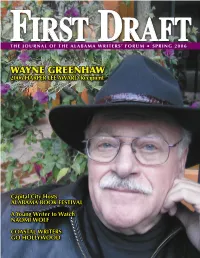

Vol. 12, No.2 / Spring 2006

THE JOURNAL OF THE ALABAMA WRITERS’ FORUM FIRST DRAFT• SPRING 2006 WAYNE GREENHAW 2006 HARPER LEE AWARD Recipient Capital City Hosts ALABAMA BOOK FESTIVAL A Young Writer to Watch NAOMI WOLF COASTAL WRITERS GO HOLLYWOOD FY 06 BOARD OF DIRECTORS BOARD MEMBER PAGE President LINDA HENRY DEAN Auburn Words have been my life. While other Vice-President ten-year-olds were swimming in the heat of PHILIP SHIRLEY Jackson, MS summer, I was reading Gone with the Wind on Secretary my screened-in porch. While my friends were JULIE FRIEDMAN giggling over Elvis, I was practicing the piano Fairhope and memorizing Italian musical terms and the Treasurer bios of each composer. I visited the local library DERRYN MOTEN Montgomery every week and brought home armloads of Writers’ Representative books. From English major in college to high JAMES A. BUFORD, JR. school English teacher in my early twenties, Auburn I struggled to teach the words of Shakespeare Writers’ Representative and Chaucer to inner-city kids who couldn’t LINDA C. SPALLA read. They learned to experience the word, even Huntsville Linda Spalla serves as Writers’ Repre- DARYL BROWN though they couldn’t read it. sentative on the AWF Executive Com- Florence Abruptly moving from English teacher to mittee. She is the author of Leading RUTH COOK a business career in broadcast television sales, Ladies and a frequent public speaker. Birmingham I thought perhaps my focus would be dif- JAMES DUPREE, JR. fused and words would lose their significance. Surprisingly, another world of words Montgomery appeared called journalism: responsibly chosen words which affected the lives of STUART FLYNN Birmingham thousands of viewers. -

Rosa Parks and the Black Freedom Struggle in Detroit Downloaded From

Jeanne Theoharis “The northern promised land that wasn’t”: Rosa Parks and the Black Freedom Struggle in Detroit Downloaded from n 2004, researchers asked could stand to be pushed”—42- high school students across year-old Rosa Parks refused to give Ithe U.S. to name their top ten up her seat on the bus. This was “most famous Americans in his- not the first time she had resisted tory” (excluding presidents) from on the bus, and numerous other http://maghis.oxfordjournals.org/ “Columbus to the present day.” black Montgomerians had also Sixty percent listed Rosa Parks, who been evicted or arrested over the was second in frequency only to years for their resistance to bus Martin Luther King, Jr (1). There is segregation. For the next 381 days, perhaps no story of the civil rights faced with city intransigence, police movement more familiar to stu- harassment, and a growing White dents than Rosa Parks’ heroic 1955 Citizens’ Council, Rosa Parks, along- bus stand in Montgomery, Alabama side hundreds of other Montgomeri- and the year-long boycott that ans, worked tirelessly to maintain ensued. And yet, perhaps because the boycott. On December 20, 1956, at University of Birmingham on August 24, 2015 of its fame, few histories are more with the Supreme Court’s decision mythologized. In the fable, racial outlawing bus segregation, Mont- injustice was rampant in the South gomery’s buses were desegregated. (but not the rest of the nation). A Yet the story is even more quiet seamstress tired from a day’s multi-dimensional than previously work without thought refused to recognized. -

Descriptive Notes: Summer 1994

Descriptive Notes: Summer 1994 Descriptive Notes The Newsletter of the Description Section of the Society of American Archivists Summer 1994 NewsNotes International work, the Internet, and Integration the focus of description funds, sweat, and years A project to prepare a guide to Catholic Diocesan Archives in East Central Europe recently received a grant from the Special Projects in Library and Information Science program of IREX, the International Research and Exchanges Board, to support communications and travel. The project is coordinated by James P. Niessen, who is overseeing the work in Hungary and Romania; Kinga Perzynska of the Catholic Archives of Texas is overseeing the work in Poland; and Vladimir Kajlik of the University of Michigan and Wayne State University of overseeing the work in the Czech Republic and Slovakia. The end result of the project will be a printed directory with basic repository and holdings information for the eighty dioceses in the target countries, and a database in CD-ROM or RLIN with multiple provenance/name/subject/language/date access points for the component collections. Please direct inquiries and comments to James P. Niessen/610 W. 30th Apt. 215/Austin, TX 78705 or e-mail: <[email protected]>. Approximately 75% of the holdings of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin Archives Division are now available for on-line searching via the Internet. Catalog descriptions of 13,000 Wisconsin state government agencies, state and local government record series, and manuscript collections are included now, and retrospective conversion will add another 2000 entries by Fall 1994. Current conversion work is funded by a Title IIC grant from the U.S. -

GEORGE WALLACE, SPEECH at SERB HALL (26 March 1976)

Voices of Democracy 11 (2016): 44-70 Hogan 44 GEORGE WALLACE, SPEECH AT SERB HALL (26 March 1976) J. Michael Hogan The Pennsylvania State University Abstract This essay seeks to account for the persuasive appeal of George C. Wallace’s campaign rally addresses. The firebrand southern governor and perennial presidential candidate drew a large national following in the late 1960s and early 1970s with speeches that defied all the rules and norms of presidential politics. Yet they invoked passionate commitment within an especially disaffected segment of the American electorate. Utilizing survey date, this essay challenges the conventional portrait of Wallace and the Wallacites, demonstrating that Wallace’s appeal was rooted not so much in conservative politics as in feelings of political alienation, persecution, and pessimism. Accounting for the Wallace phenomenon in terms of a classic, Hofferian theory of social protest, the essay concludes by reflecting on the parallels between Wallace and Donald J. Trump’s 2016 presidential election. Keywords: George C. Wallace, presidential campaigns, campaign rallies, political disaffection, true believers. In 1964, George Wallace became a national figure when he launched his first campaign for the presidency with little money, no campaign organization, and an impressive array of critics and adversaries in the media, the churches, the labor movement, and the political mainstream.1 Surprising almost everybody, he showed remarkable strength in northern Democratic primaries and focused attention on his favorite target: the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In 1968, Wallace faced the same barriers and more. His decision to run as a third-party candidate added the challenge of a political system rigged to favor the two major-party candidates.2 Despite those obstacles, Wallace tallied 10 million votes—the most popular votes ever for a third party candidate in U.S. -

Download and Goals the Same

Winter / Spring 2010 MOSAICThe magazine of the Alabama Humanities Foundation Still Learning from Mockingbird Behind the V-2 missile Celebrate Black History Month with a Road Scholar presentation ahf.net Alabama Humanities Foundation Board Our kudzu philosophy: of Directors At AHF, we think we have a lot to learn from kudzu, or at least its concept. Bob Whetstone*, Chair, Birmingham Like it or hate it, kudzu is truly a ubiquitous Jim Noles, Vice Chair, Birmingham Danny Patterson, Secretary, Mobile feature of Alabama as well as our Southern John Rochester, Treasurer, Ashland neighbors. No matter who you are, Lynne Berry*, Huntsville where you’re from or how deeply you’re Calvin Brown*, Decatur rooted in the humanities, if you know Marthanne Brown*, Jasper Alabama, you know kudzu. Pesky as it may Malik Browne, Eutaw Rick Cook, Auburn be, the plant is common to everyone. Kudzu Cathy Crenshaw, Birmingham spreads and grows, links and connects. And David Donaldson, Birmingham much like the rich humanities in our state, Kathleen Dotts, Huntsville kudzu can be found, well, everywhere. Reggie Hamner, Montgomery Janice Hawkins*, Troy Kay Kimbrough, Mobile John Knapp, Birmingham Lisa Narrell-Mead, Birmingham Robert Olin, Tuscaloosa Carolyn Reed, Birmingham Guin Robinson, Birmingham archaeology art history classics film studies history Nancy Sanford, Sheffield Lee Sentell*, Montgomery Dafina Ward, Birmingham Wyatt Wells, Montgomery Billie Jean Young, Marion *denotes governor’s appointee jurisprudence languages literature philosophy & ethics theatre history Alabama Humanities The Alabama Humanities Foundation (AHF), founded in 1974, is the state nonprofit affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Foundation Staff Bob Stewart, Executive Director The Alabama Humanities Foundation. -

Martha Moon Fluker Local and State History Collection

Martha Moon Fluker Local and State History Collection Drawer 1: A & B Folder 1: Actors Item 1: “‘Gomer Pyle’ Comes Home,” By Wayne Greenhaw (Jim Nabors, “Gomer Pyle”) The Advertiser Journal Alabama, January 16, 1966 Item 2: “Montevallo recognizes TV actress,” (Polly Holliday) The Tuscaloosa News, January 26, 1983 Item 3: “Wayne Rogers Keeping Cool About Series,” By Bob Thomas, (Wayne Rogers). The Birmingham News, February 13, 1975 Folder 2: Agriculture Item 1: “Agriculture income up $94 million,” By Thomas E. Hill. The Birmingham News, January 11, 1976. Item2: “Alabama Agribusiness Vol. 18, NO. 2” - “Introduction to Farm Planning, Modern Techniques,” By Sidney C. Bell - “Enterprise Budgeting,” By Terry R. Crews and Lavaugh Johnson - “On Farm Use of Computers and Programmable Calculators,” By Douglas M. Henshaw and Charles L. Maddox Item 3: “Beetle and Fire ant still big problem,” By Ed Watkins. The Tuscaloosa News, October 10, 1979. Item 4: “Hurricane damaged to timber unknown.” The Meridian Star, October 1, 1979. Item 5: “Modern Techniques in Farm Planning,” Auburn University, January 23-24, 1980 Item 6: “October 1971 Alabama Agricultural Statistics,” (Bulletin 14) Item 7: “1982 Census of Agriculture,” (Preliminary Report) Folder 3: Alabama – Census Item 1: Accent Alabama, (Vol. 2, No. 2, June, 1981). [3] - “1980 Census: Population Changes by Race” Item 2: “Standard Population Projections,” August, 1983 (Alabama Counties). [5] Item 3: “U.S. Census of population Preliminary – 1980” Folder 4: Alabama – Coat of Arms Item 1: “Alabama Coat of Arms.” The Advertiser – Journal, Sunday, January 3, 1965. Item 2: “Alabama’s New Coat of Arms.” The Birmingham News, Sunday, April 23, 1939. -

Download This List

NewSouth Books 105 South Court Street, Montgomery, AL 36104 • 334-834-3556 • www.newsouthbooks.com Selected Books About Montgomery, Alabama — A Reading List MONTGOMERY HISTORY/GENERAL An Alabama Newspaper Tradition: Grover C. Hall and the Hall Family, Daniel Hollis, University of Alabama Press, 1983. An American Harvest: The Story of Weil Brothers Cotton, George Bush, Prentice Hall Trade, 1983. Central Alabama Memories: Commemorating the 175th Anniversary of the Montgomery Advertiser, Montgomery Advertiser, Pediment Publishing, 2004. Cloverdale: An Illustrated History, Suzanne Samuel Israel, King Kudzu Publications, 2001. Confederate Home Front: Montgomery During the Civil War, Dr. William Rogers Jr., University of Alabama Press, 2001. The Cradle: An Anatomy of a Town, Fact and Fiction, John P. Kohn Jr., Vantage Press, 1969 Deep Family: Four Centuries of American Originals and Southern Eccentrics [Read-Baldwin- Craik family], Nicholas Cabell Read, Dallas Read, and Jean Craik Read, NewSouth Books, 2005. Doing It My Way, Winton (Red) Blount, Greenwich Publishing Group, 1996. History of Huntingdon College, 1854–1954, Rhoda Coleman Ellison, NewSouth Books, 2004. Memories of the Mount: The Story of Mt. Meigs, Alabama, John Scott, Black Belt Press, 1993. Montgomery: Andrew Dexter's Dream City, Helen Blackshear, The Author, 1996. Montgomery: An Illustrated History, Wayne Flynt, Windsor Publications, 1980. Montgomery at the Forefront of a New Century, Wendi Lewis and Marty Ellis, Community Communications, 1996. Montgomery Aviation, Billy Singleton, Arcadia Publishing, 2007. Montgomery: Capital City Corners, Mary Ann Neeley, Arcadia Publishing, 1997. Montgomery's Historic Neighborhoods, Carole King and Karren Pell, Arcadia Publishing, 2010. Montgomery in the Good War: Portrait of a Southern City, 1939–1946, Wesley Newton, University of Alabama Press, 2000. -

Walter De Vries: <E±Stma-F^W*** •

Interview with Bill Baxley, attorney general of Alabama, July 9, 197^, conducted by Jack Bass and Walter De Vries, transcribed by Linda Killen. Baxley:—he had a lot of human feelings. A lot of us have, I reckon. Kept him from doing a lot of it, but at least he really, honestly be lieved in what he said and he said it at a time when it was unpopular. So I've been a fan of his a long time. Really kind of a tragic figure. Walter De Vries: <e±stma-f^W*** • Baxley: Yeah. W.D.V.: How's he doing now? Baxley: Oh, he's penniless. Lives on a little pension that Wallace got passed for him. Doesn't pay any bills. They even took his tele phone out of his house. Sad, tragic figure. W.D.V.: Did he do any campaigning? Baxley: Oh, as a joke he puts his name on a ballot. Just a little joke. Really. .. to goad Wallace. W.D.V.: What did your father do? Baxley$ He was a lawyer and a circuit judge down in south Alabama. Very nonpolitical. He was a student of the law. Real, old scholar. Didn't know anything about politics. Didn't care anything about it. Hated the fact that I was interested in it. W.D.V.: How did you get involved in it? Baxley: Well, when I was a kid the only two things I wanted to be was either a major league baseball player or a politician. And I found out I might not be a good politician, but I'm a better politician than I was a ball player, I reckon. -

July 2006 Vol.67, No

-. • . I ~* ~/~~ : 0ur Success! * 't*" 1~ its insureds. Isn't it time you JOINED THE MOVEMENT and insured with AIM? AIM: For the Difference! Attorneys Insurance Mutual of Alabama, Inc. 200 Inverness Parkway Telephone (205) 980-0009 Toll Free (800) 526-1246 Birmingham , Alabama 35242-4813 FAX (205) 980-9009 Service • Strength • Sec u rity [ml -UT.lffl ISI ALABAMA --ll dh•iJion o/-- [NS URAN CE SPECIALISTS, INC. ISi ALABAMA, a division of Insurance Specialists, Inc . ( ISi), in its fift h decade of service to the national association marketplace, is proud to have maintained service to the Alabama State Bar since 1972. ISi is recogni7.£<1as a leader among affinity third party administrators, and maintains strong affiliations with leading carriers of its specialty products. Association and affi.nity gro ups provide added value to Membership benefits through offerings of these qua.lity insurance plans tailored to meet the needs of Members. INSURANCE PROGRAMS AVAILABLE TO ALABAMA STATE BAR MEMBERS Select tlie products tlrat you want i11formatio11011 from tlie list below, complete tlie form and retum via fax or mail. Tlrere is 110 obligation. 0 Long Term Disability 0 AccidentaJ Death & Dismemberment Plan D Individual Tenn Life 0 Business Overhead Expense 0 Hospital Income Plan D Medica re Supp lement Plan Alahlnu S1:1teBnt Mt:fflbn N11mc AJI< Spou~NarM ,.,.. ' ordq)c-ndcntJ OffictAddtffl (Sum, Ory.Sr,1tt,Zip) OfficePhone HomePhone Fu Q«upat1on E-mailAddm.a: 0,/1 me for 011 appointmelllto discwscoverage at: O Home D Office RETURN COMPLETED REPLY CARD TO: Fax: 843-525-9992 Mail:[$[ ADMINISTRATIVBCENTBII • SALES · P.O.