Challenges of Humanistic Psychology for Secondary Education Walter P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Healthy Personality

HEALTHY PERSONALITY Presented by CONTINUING PSYCHOLOGY EDUCATION 6 CONTINUING EDUCATION HOURS “I wanted to prove that human beings are capable of something grander than war and prejudice and hatred.” Abraham Maslow, Psychology Today, 1968, 2, p.55. Course Objective Learning Objectives The purpose of this course is to provide an Upon completion, the participant will understand understanding of the concept of healthy personality. the nature, motivation, and characteristics of the Seven theorists offer their views on the subject, healthy personality. Seven influential including: Gordon Allport, Carl Rogers, Erich psychotherapists-theorists examine the concept Fromm, Abraham Maslow, Carl Jung, Viktor of healthy personality allowing the reader to Frankl, and Fritz Perls. integrate these principles into his or her own life. Accreditation Faculty Continuing Psychology Education is approved to Neil Eddington, Ph.D. provide continuing education by the following: Richard Shuman, LMFT Texas State Board of Social Worker Examiners (Provider # CS3329) - 5 hours for this course; Texas State Board of Examiners of Professional Counselors (LPC Provider # 2013) - 6 hours for this course; Texas State Board of Examiners of Marriage and Family Therapists - 6 hours for this course; this course meets the qualifications for 6 hours of continuing education for Psychologists, LSSPs, LPAs, and Provisionally Licensed Psychologists as required by the Texas State Board of Examiners of Psychologists. Mission Statement Continuing Psychology Education provides the highest quality continuing education designed to fulfill the professional needs and interests of mental health professionals. Resources are offered to improve professional competency, maintain knowledge of the latest advancements, and meet continuing education requirements mandated by the profession. -

A Century of Social Psychology: Individuals, Ideas, and Investigations GEORGE R

1 A Century of Social Psychology: Individuals, Ideas, and Investigations GEORGE R. GOETHALS ^ f INTRODUCTION This chapter tells an exciting story of intellectual discovery. At the start of the twentieth century, social psy- chology began addressing age-old philosophical questions using scientific methods. What was the nature of human nature, and did the human condition make it possible for people to work together for good rather than for evil? Social pschology first addressed these questions by looking at the overall impact of groups on individuals and then began to explore more refined questions about social influence and social perception. How do we understand persuasion, stereotypes and prejudice, differences between men and women, and how culture affects thoughts and behavior? In 1954, in his classic chapter on the historical govem themselves. In The Republic, Plato argued that background of modem social psychology, Gordon men organize themselves and form governments Allport nominated Auguste Comte as the founder because they cannot achieve all their goals as of social psychology as a science. He noted that individuals. They are interdependent. Some kind of Comte, the French philosopher and founder of social organization is required. Various forms emerge, positivism, had previously, in 1839, identified depending on the situation, including aristocracy, sociology as a separate discipline. In fact, sociology oligarchy, democracy, and tyranny. Plato clearly did not really exist, but Comte saw it coming. favored aristocracy, where the wise and just govern, Allport notes that 'one might say that Comte and allow individuals to develop their full potential. christened sociology many years before it was Whatever the form, social organization and govem- born' (Allport, 1968: 6). -

Hierarchy of Needs – Abraham Maslow; 1943 (Content Theory)

Hierarchy of Needs – Abraham Maslow; 1943 (Content Theory) What is the Theory? Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is a theory in psychology proposed by the American psychologist Abraham Maslow in his 1943 paper “A Theory of Human Motivation”. Maslow developed a theory that suggests we are motivated to satisfy five basic needs. These needs are arranged in a hierarchy. Maslow suggests that we seek first to satisfy the lowest level of needs. Once this is done, we seek to satisfy each higher level of need until we have satisfied all five needs. While modern research shows some shortcomings with this theory, Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Theory remains an important and simple motivation tool for managers to understand and apply. The Hierarchy of Needs is as follows: 1. Physiological Needs (basic issues of survival such as salary, stable employment, able to eat/drink/sleep well) 2. Security Needs (stable physical and emotional environment issues such as benefits, pension, safe work environment, and fair work practices; job security) 3. “Belongingness” Needs (social acceptance issues such as friendship or cooperation on the job; feeling part of a group/team) 4. Esteem Needs (positive self-image and respect and recognition issues such as job titles, nice work spaces, and prestigious job assignments; being recognised for achievements/improvements) 5. Self-Actualization Needs (achievement issues such as workplace autonomy, challenging work, and subject matter expert status on the job, the need for personal growth and development) Extracts taken from https://managementisajourney.com/motivation-applying-maslows-hierarchy-of-needs-theory/ 1 Hierarchy of Needs – Abraham Maslow; 1943 (Content Theory) How to Apply this Theory to the Workplace 1. -

The Transpersonal William James

THE TRANSPERSONAL WILLIAM JAMES Mark B. Ryan, Ph.D. Cholula, Puebla, Mexico ABSTRACT: Transpersonal psychologists often speculate on who was their ‘‘first’’ pioneer, commonly with reference to Carl Jung. A look at the early development of modern psychology, however, reveals various figures who accepted a spiritual and collective dimension of the psyche, among them William James. Out of a tension between scientific and religious outlooks embodied in his own life and thought, James had embraced and articulated the principal elements of a transpersonal orientation by the early twentieth century, and had given them a metaphysical and empirical justification on which they still can stand today. We can see those elements in four aspects of his thought: first, in what he chose to study, especially in his interest in psychic and religious experience; second, in his definition of true science and his refutation of materialism; third, in his concept of consciousness; and fourth, in his defense of the validity of spiritual experience. ‘‘100 Years of Transpersonal Psychology’’: the title and description of the Association for Transpersonal Psychology conference in September, 2006, represented a milestone in the official recognition of William James’s place in the origins of modern transpersonal thought. As the conference’s official announcement declared, James made the first recorded use of the term ‘‘transpersonal’’ in 1905. The conference’s title took its measure of a century from that coinage, suggesting a major role for James in the founding of the field. The occasion of James’s use of the term was modest: an unpublished document, merely a printed course syllabus at Harvard University for an introductorycourse in philosophy (Vich, 1998). -

Who Is Abraham Maslow?

WHO IS ABRAHAM MASLOW? A SHORT READING J WHO IS ABRAHAM MASLOW? • Abraham Maslow was an American psychologist. • Psychology is the scientific study of the mind and behavior. • Best known for Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs • He stressed the importance of focusing on the positive qualities of people. • During his time, psychologists were usually focused on the abnormal and ill. • Maslow focused on positive mental health. WHAT IS MASLOW KNOWN FOR? MASLOW’S HIERARCHY OF NEEDS • Maslow described that people will be motivated to achieve certain needs, and some needs will take priority over others. • The first need is for physical survival, and that will be what motivates a person’s behavior. • Once that need is met, the next level of needs is what will motivate a person’s behavior. WHAT ARE THE NEEDS? PHYSIOLOGICAL • Most important needs to have met • Biological requirements for human survival • air, food, drink, shelter, clothing, warmth, sex, sleep SAFETY • People want to experience order, predictability and control in their lives. • These needs can be fulfilled by the family and society • Police, schools, business and medical care LOVE AND BELONGINGNESS • The third level of human needs is social and involves feelings of belongingness. The need for interpersonal relationships motivates behavior. • Examples include friendship, intimacy, trust, and acceptance, receiving and giving affection and love. Affiliating, being part of a group (family, friends, work). ESTEEM • The fourth level in Maslow’s hierarchy - which Maslow classified into two categories: 1. esteem for oneself (dignity, achievement, mastery, independence) and 2. the desire for reputation or respect from others (status, prestige). -

Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs in an Inclusion Classroom- by Kaitlin Lutz

Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs in an Inclusion Classroom- By Kaitlin Lutz (/Maslow%27s+Hierarchy+of+Needs+in+an+Inclusion+Classroom- +By+Kaitlin+Lutz) # Edit ! 0 (/Maslow%27s+Hierarchy+of+Needs+in+an+Inclusion+Classroom-+By+Kaitlin+Lutz#discussion) " 3 (/page/history/Maslow%27s+Hierarchy+of+Needs+in+an+Inclusion+Classroom-+By+Kaitlin+Lutz) … (/page/menu/Maslow%27s+Hierarchy+of+Needs+in+an+Inclusion+Classroom-+By+Kaitlin+Lutz) All students have basic needs to be met for learning to occur. The more needs that are met, the more students will learn. Maslow's hierarchy, developed by Abraham Maslow in 1954, is a way of organizing the basic needs of students on different levels (McLeod, 2007). The more levels that are met, the more a student will learn. Maslow's hierarchy of needs applies especially to students with exceptionalities, because many times students' with exceptionalities needs are more difficult to meet. Abraham Maslow http://thesocialworkexam.com/maslows-theory-of-basic-needs-learning What is Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs? According to Gorman in the Aboriginal and Islander Health Worker Journal, there are six levels to Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs. The first level is physiological needs. The first level must be met in order to move onto any other levels in the hierarchy. Physiological needs include the basic necessities of life (Gorman, 2010). These needs may include food, water, and shelter. Once physiological needs are met, students will then need the second level of Maslow's hierarchy. The second level is safety needs. Students need to feel safe in the environment in which they are learning with no outside threats. -

Introduction to Political Psychology

INTRODUCTION TO POLITICAL PSYCHOLOGY This comprehensive, user-friendly textbook on political psychology explores the psychological origins of political behavior. The authors introduce read- ers to a broad range of theories, concepts, and case studies of political activ- ity. The book also examines patterns of political behavior in such areas as leadership, group behavior, voting, race, nationalism, terrorism, and war. It explores some of the most horrific things people do to each other, as well as how to prevent and resolve conflict—and how to recover from it. This volume contains numerous features to enhance understanding, includ- ing text boxes highlighting current and historical events to help students make connections between the world around them and the concepts they are learning. Different research methodologies used in the discipline are employed, such as experimentation and content analysis. This third edition of the book has two new chapters on media and social movements. This accessible and engaging textbook is suitable as a primary text for upper- level courses in political psychology, political behavior, and related fields, including policymaking. Martha L. Cottam (Ph.D., UCLA) is a Professor of Political Science at Washington State University. She specializes in political psychology, inter- national politics, and intercommunal conflict. She has published books and articles on US foreign policy, decision making, nationalism, and Latin American politics. Elena Mastors (Ph.D., Washington State University) is Vice President and Dean of Applied Research at the American Public University System. Prior to that, she was an Associate Professor at the Naval War College and held senior intelligence and policy positions in the Department of Defense. -

Personality Traits

Personality Traits SECOND EDITION GERALD MATTHEWS University of Cincinnati IAN J. DEARY University of Edinburgh MARTHA C. WHITEMAN University of Edinburgh published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge, CB2 2RU, UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011–4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarc´on 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Cambridge University Press 2003 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 1998. Reprinted 1999, 2000, 2002 Second edition 2003 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typefaces Times 10/13 pt. Formata System LATEX2ε [TB] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Matthews, Gerald. Personality traits / Gerald Matthews, Ian J. Deary, Martha C. Whiteman. – 2nd edn. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0 521 83107 5 – ISBN 0 521 53824 6 (pb) 1. Personality. I. Deary, Ian J. II. Whiteman, Martha C. III. Title. BF698.M3434 2003 155.23 – dc21 2003046259 ISBN 0 521 83107 5 hardback ISBN 0 521 53824 6 paperback The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. -

Trends in the History of Contemporary Social Psychology: a Quantitative Analysis Pamela Hewitt Ol Y

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Winter 1976 TRENDS IN THE HISTORY OF CONTEMPORARY SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY: A QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS PAMELA HEWITT OL Y Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation LOY, PAMELA HEWITT, "TRENDS IN THE HISTORY OF CONTEMPORARY SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY: A QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS" (1976). Doctoral Dissertations. 1143. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/1143 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original subm itted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from die document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

Graphology: an Interface Between Biology, Psychology and Neuroscience

PSYCHOLOGICAL DISORDERS AND RESEARCH | ISSN 2613-7828 Available online at www.sciencerepository.org Science Repository Review Article Graphology: An Interface Between Biology, Psychology and Neuroscience Giuseppe Marano1,2,3,4, Gianandrea Traversi5, Eleonora Gaetani6, Gabriele Sani1, Salvatore Mazza1 and Marianna Mazza1* 1Institute of Psychiatry and Psychology, Department of Geriatrics, Neuroscience and Orthopedics, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Rome, Italy 2Associazione Grafologica Italo-Francese (AGIF), Italy 3Istituto Analisi Grafologiche (IANG), Italy 4Associazione Grafologi Professionisti (AGP), Italy 5Department of Science, University of Rome “Roma Tre”, Rome, Italy 6Division of Internal Medicine and Gastroenterology, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Rome, Italy A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Article history: Handwriting analysis dates back to many centuries ago. Graphology is a discipline that investigates Received: 19 December, 2020 personality and intellect of the individual through writing, indeed handwriting of the human being is an Accepted: 29 December, 2020 expression of his or her essence. Graphology examines a writing in order to extract unfiltered information Published: 7 January, 2021 about innate temperament and subconscious nature of who has traced the letters. The present paper Keywords: highlights the historical and methodological approaches of graphology and its usefulness in human Graphology knowledge in order to give a glimpse of the complexity of this discipline. We have gradually focused on the handwriting description of the various fields with which, over time until today, the graphologists have dealt according psychology to experimental and epistemological methodologies along a spectrum that ranges from studies on the neurosciences character, the neuronal and biological correlates, the use in the forensic field, until to the contributions to biology career counseling and personnel selection. -

Download Article (PDF)

2013 International Conference on Advances in Social Science, Humanities, and Management (ASSHM 2013) The Beauty of the Transcending of the Humanity --Research on Maslow’s Self-actualization Theory Liu Hongyu1 Han Lu2 1The School of Psychology and Cognitive Science of East China Normal Unversity 2The School of Art and Design of Wuhan Textile University Abstract: but also the highest value goal of the entire Abraham Harold Maslow is a world-renowned psychology and ethics. Maslow's psychology social psychologist, personality theorist and an and ethics are built around one center, i.e., man expert at comparative psychology. Maslow has or humanity. It is human-centered and based on also made great achievements in philosophy and humans’ needs with full realization of human literature. potential as its final goal. Maslow's theory can Maslow is a well-known scholars with his be expressed by a simple formula: human → study of self-realization in the West.The concept need (motivation) →behavior → realization of of self-realization is complex and rich in value or humanity (self-actualization is the connotation.He completed the research on the vertex). Maslow suggests that self-actualization self-fulfilling the original intention of those who is based on people's needs system rooted in are very specific,such as,to identify human genetic gene like instinct, namely the intrinsic beings,to make outstanding contributions to requirement of the realization of five needs society of people of common personality (physiology, safety, love/belonging, self-esteem, characteristics,to identify some of the positive self-actualization) from the bottom to the top, human potential value of the goal. -

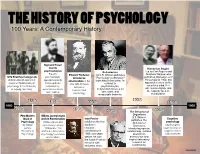

02B Psych Timeline.Pages

THE HISTORY OF PSYCHOLOGY 100 Years: A Contemporary History Sigmund Freud founds Humanism Begins psychoanalysis Behaviorism Led by Carl Rogers and Freud's Edward Titchener John B. Watson publishes Abraham Maslow, who 1879 First Psychology Lab psychoanalytic introduces "Psychology as Behavior," publishes Motivation and Personality in 1954, this Wilhelm Wundt opens first approach asserts structuralism in the launching behaviorism. In experimental laboratory in that people are contrast to approach centers on the U.S. with his book conscious mind, free psychology at the University motivated by, Manual of psychoanalysis, of Leipzig, Germany. unconscious drives behaviorism focuses on will, human dignity, and Experimental the capacity for self- and conflicts. observable and Psychology measurable behavior. actualization. 1938 1890 1896 1906 1956 1860 1960 1879 1901 1913 The Behavior of 1954 Organisms First Modern William James begins B.F. Skinner Ivan Pavlov Cognitive Book of work in Functionalism publishes The Psychology William James and publishes the first Behavior of psychology By William John Dewey, whose studies in Organisms, psychologists James, 1896 article "The classical introducing operant begin to focus on Principles of Reflex Arc Concept in conditioning in conditioning. It draws cognitive states Psychology Psychology" promotes 1906; two years attention to and processes functionalism. before, he won behaviorism and the Nobel Prize for inspires laboratory his work with research on salivating dogs. conditioning. Name _________________________________Date _________________Period __________ THE HISTORY OF PSYCHOLOGY A Contemporary History Use the timeline from the back to answer the questions. 1. What happened earlier? A) B.F. Skinner publishes The Behavior of Organism B) John B. Watson publishes Psychology as Behavior 2.