DIY Hyperbolic Geometry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geometric Manifolds

Wintersemester 2015/2016 University of Heidelberg Geometric Structures on Manifolds Geometric Manifolds by Stephan Schmitt Contents Introduction, first Definitions and Results 1 Manifolds - The Group way .................................... 1 Geometric Structures ........................................ 2 The Developing Map and Completeness 4 An introductory discussion of the torus ............................. 4 Definition of the Developing map ................................. 6 Developing map and Manifolds, Completeness 10 Developing Manifolds ....................................... 10 some completeness results ..................................... 10 Some selected results 11 Discrete Groups .......................................... 11 Stephan Schmitt INTRODUCTION, FIRST DEFINITIONS AND RESULTS Introduction, first Definitions and Results Manifolds - The Group way The keystone of working mathematically in Differential Geometry, is the basic notion of a Manifold, when we usually talk about Manifolds we mean a Topological Space that, at least locally, looks just like Euclidean Space. The usual formalization of that Concept is well known, we take charts to ’map out’ the Manifold, in this paper, for sake of Convenience we will take a slightly different approach to formalize the Concept of ’locally euclidean’, to formulate it, we need some tools, let us introduce them now: Definition 1.1. Pseudogroups A pseudogroup on a topological space X is a set G of homeomorphisms between open sets of X satisfying the following conditions: • The Domains of the elements g 2 G cover X • The restriction of an element g 2 G to any open set contained in its Domain is also in G. • The Composition g1 ◦ g2 of two elements of G, when defined, is in G • The inverse of an Element of G is in G. • The property of being in G is local, that is, if g : U ! V is a homeomorphism between open sets of X and U is covered by open sets Uα such that each restriction gjUα is in G, then g 2 G Definition 1.2. -

Black Hole Physics in Globally Hyperbolic Space-Times

Pram[n,a, Vol. 18, No. $, May 1982, pp. 385-396. O Printed in India. Black hole physics in globally hyperbolic space-times P S JOSHI and J V NARLIKAR Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Bombay 400 005, India MS received 13 July 1981; revised 16 February 1982 Abstract. The usual definition of a black hole is modified to make it applicable in a globallyhyperbolic space-time. It is shown that in a closed globallyhyperbolic universe the surface area of a black hole must eventuallydecrease. The implications of this breakdown of the black hole area theorem are discussed in the context of thermodynamics and cosmology. A modifieddefinition of surface gravity is also given for non-stationaryuniverses. The limitations of these concepts are illustrated by the explicit example of the Kerr-Vaidya metric. Keywocds. Black holes; general relativity; cosmology, 1. Introduction The basic laws of black hole physics are formulated in asymptotically flat space- times. The cosmological considerations on the other hand lead one to believe that the universe may not be asymptotically fiat. A realistic discussion of black hole physics must not therefore depend critically on the assumption of an asymptotically flat space-time. Rather it should take account of the global properties found in most of the widely discussed cosmological models like the Friedmann models or the more general Robertson-Walker space times. Global hyperbolicity is one such important property shared by the above cosmo- logical models. This property is essentially a precise formulation of classical deter- minism in a space-time and it removes several physically unreasonable pathological space-times from a discussion of what the large scale structure of the universe should be like (Penrose 1972). -

Models of 2-Dimensional Hyperbolic Space and Relations Among Them; Hyperbolic Length, Lines, and Distances

Models of 2-dimensional hyperbolic space and relations among them; Hyperbolic length, lines, and distances Cheng Ka Long, Hui Kam Tong 1155109623, 1155109049 Course Teacher: Prof. Yi-Jen LEE Department of Mathematics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong MATH4900E Presentation 2, 5th October 2020 Outline Upper half-plane Model (Cheng) A Model for the Hyperbolic Plane The Riemann Sphere C Poincar´eDisc Model D (Hui) Basic properties of Poincar´eDisc Model Relation between D and other models Length and distance in the upper half-plane model (Cheng) Path integrals Distance in hyperbolic geometry Measurements in the Poincar´eDisc Model (Hui) M¨obiustransformations of D Hyperbolic length and distance in D Conclusion Boundary, Length, Orientation-preserving isometries, Geodesics and Angles Reference Upper half-plane model H Introduction to Upper half-plane model - continued Hyperbolic geometry Five Postulates of Hyperbolic geometry: 1. A straight line segment can be drawn joining any two points. 2. Any straight line segment can be extended indefinitely in a straight line. 3. A circle may be described with any given point as its center and any distance as its radius. 4. All right angles are congruent. 5. For any given line R and point P not on R, in the plane containing both line R and point P there are at least two distinct lines through P that do not intersect R. Some interesting facts about hyperbolic geometry 1. Rectangles don't exist in hyperbolic geometry. 2. In hyperbolic geometry, all triangles have angle sum < π 3. In hyperbolic geometry if two triangles are similar, they are congruent. -

Examples of Manifolds

Examples of Manifolds Example 1 (Open Subset of IRn) Any open subset, O, of IRn is a manifold of dimension n. One possible atlas is A = (O, ϕid) , where ϕid is the identity map. That is, ϕid(x) = x. n Of course one possible choice of O is IR itself. Example 2 (The Circle) The circle S1 = (x,y) ∈ IR2 x2 + y2 = 1 is a manifold of dimension one. One possible atlas is A = {(U , ϕ ), (U , ϕ )} where 1 1 1 2 1 y U1 = S \{(−1, 0)} ϕ1(x,y) = arctan x with − π < ϕ1(x,y) <π ϕ1 1 y U2 = S \{(1, 0)} ϕ2(x,y) = arctan x with 0 < ϕ2(x,y) < 2π U1 n n n+1 2 2 Example 3 (S ) The n–sphere S = x =(x1, ··· ,xn+1) ∈ IR x1 +···+xn+1 =1 n A U , ϕ , V ,ψ i n is a manifold of dimension . One possible atlas is 1 = ( i i) ( i i) 1 ≤ ≤ +1 where, for each 1 ≤ i ≤ n + 1, n Ui = (x1, ··· ,xn+1) ∈ S xi > 0 ϕi(x1, ··· ,xn+1)=(x1, ··· ,xi−1,xi+1, ··· ,xn+1) n Vi = (x1, ··· ,xn+1) ∈ S xi < 0 ψi(x1, ··· ,xn+1)=(x1, ··· ,xi−1,xi+1, ··· ,xn+1) n So both ϕi and ψi project onto IR , viewed as the hyperplane xi = 0. Another possible atlas is n n A2 = S \{(0, ··· , 0, 1)}, ϕ , S \{(0, ··· , 0, −1)},ψ where 2x1 2xn ϕ(x , ··· ,xn ) = , ··· , 1 +1 1−xn+1 1−xn+1 2x1 2xn ψ(x , ··· ,xn ) = , ··· , 1 +1 1+xn+1 1+xn+1 are the stereographic projections from the north and south poles, respectively. -

An Introduction to Topology the Classification Theorem for Surfaces by E

An Introduction to Topology An Introduction to Topology The Classification theorem for Surfaces By E. C. Zeeman Introduction. The classification theorem is a beautiful example of geometric topology. Although it was discovered in the last century*, yet it manages to convey the spirit of present day research. The proof that we give here is elementary, and its is hoped more intuitive than that found in most textbooks, but in none the less rigorous. It is designed for readers who have never done any topology before. It is the sort of mathematics that could be taught in schools both to foster geometric intuition, and to counteract the present day alarming tendency to drop geometry. It is profound, and yet preserves a sense of fun. In Appendix 1 we explain how a deeper result can be proved if one has available the more sophisticated tools of analytic topology and algebraic topology. Examples. Before starting the theorem let us look at a few examples of surfaces. In any branch of mathematics it is always a good thing to start with examples, because they are the source of our intuition. All the following pictures are of surfaces in 3-dimensions. In example 1 by the word “sphere” we mean just the surface of the sphere, and not the inside. In fact in all the examples we mean just the surface and not the solid inside. 1. Sphere. 2. Torus (or inner tube). 3. Knotted torus. 4. Sphere with knotted torus bored through it. * Zeeman wrote this article in the mid-twentieth century. 1 An Introduction to Topology 5. -

The Sphere Project

;OL :WOLYL 7YVQLJ[ +XPDQLWDULDQ&KDUWHUDQG0LQLPXP 6WDQGDUGVLQ+XPDQLWDULDQ5HVSRQVH ;OL:WOLYL7YVQLJ[ 7KHULJKWWROLIHZLWKGLJQLW\ ;OL:WOLYL7YVQLJ[PZHUPUP[PH[P]L[VKL[LYTPULHUK WYVTV[LZ[HUKHYKZI`^OPJO[OLNSVIHSJVTT\UP[` /\THUP[HYPHU*OHY[LY YLZWVUKZ[V[OLWSPNO[VMWLVWSLHMMLJ[LKI`KPZHZ[LYZ /\THUP[HYPHU >P[O[OPZ/HUKIVVR:WOLYLPZ^VYRPUNMVYH^VYSKPU^OPJO [OLYPNO[VMHSSWLVWSLHMMLJ[LKI`KPZHZ[LYZ[VYLLZ[HISPZO[OLPY *OHY[LYHUK SP]LZHUKSP]LSPOVVKZPZYLJVNUPZLKHUKHJ[LK\WVUPU^H`Z[OH[ YLZWLJ[[OLPY]VPJLHUKWYVTV[L[OLPYKPNUP[`HUKZLJ\YP[` 4PUPT\T:[HUKHYKZ This Handbook contains: PU/\THUP[HYPHU (/\THUP[HYPHU*OHY[LY!SLNHSHUKTVYHSWYPUJPWSLZ^OPJO HUK YLÅLJ[[OLYPNO[ZVMKPZHZ[LYHMMLJ[LKWVW\SH[PVUZ 4PUPT\T:[HUKHYKZPU/\THUP[HYPHU9LZWVUZL 9LZWVUZL 7YV[LJ[PVU7YPUJPWSLZ *VYL:[HUKHYKZHUKTPUPT\TZ[HUKHYKZPUMV\YRL`SPMLZH]PUN O\THUP[HYPHUZLJ[VYZ!>H[LYZ\WWS`ZHUP[H[PVUHUKO`NPLUL WYVTV[PVU"-VVKZLJ\YP[`HUKU\[YP[PVU":OLS[LYZL[[SLTLU[HUK UVUMVVKP[LTZ"/LHS[OHJ[PVU;OL`KLZJYPILwhat needs to be achieved in a humanitarian response in order for disaster- affected populations to survive and recover in stable conditions and with dignity. ;OL:WOLYL/HUKIVVRLUQV`ZIYVHKV^ULYZOPWI`HNLUJPLZHUK PUKP]PK\HSZVMMLYPUN[OLO\THUP[HYPHUZLJ[VYH common language for working together towards quality and accountability in disaster and conflict situations ;OL:WOLYL/HUKIVVROHZHU\TILYVMºJVTWHUPVU Z[HUKHYKZ»L_[LUKPUNP[ZZJVWLPUYLZWVUZL[VULLKZ[OH[ OH]LLTLYNLK^P[OPU[OLO\THUP[HYPHUZLJ[VY ;OL:WOLYL7YVQLJ[^HZPUP[PH[LKPU I`HU\TILY VMO\THUP[HYPHU5.6ZHUK[OL9LK*YVZZHUK 9LK*YLZJLU[4V]LTLU[ ,+0;065 7KHB6SKHUHB3URMHFWBFRYHUBHQBLQGG The Sphere Project Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Humanitarian Response Published by: The Sphere Project Copyright@The Sphere Project 2011 Email: [email protected] Website : www.sphereproject.org The Sphere Project was initiated in 1997 by a group of NGOs and the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement to develop a set of universal minimum standards in core areas of humanitarian response: the Sphere Handbook. -

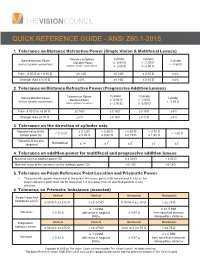

Quick Reference Guide - Ansi Z80.1-2015

QUICK REFERENCE GUIDE - ANSI Z80.1-2015 1. Tolerance on Distance Refractive Power (Single Vision & Multifocal Lenses) Cylinder Cylinder Sphere Meridian Power Tolerance on Sphere Cylinder Meridian Power ≥ 0.00 D > - 2.00 D (minus cylinder convention) > -4.50 D (minus cylinder convention) ≤ -2.00 D ≤ -4.50 D From - 6.50 D to + 6.50 D ± 0.13 D ± 0.13 D ± 0.15 D ± 4% Stronger than ± 6.50 D ± 2% ± 0.13 D ± 0.15 D ± 4% 2. Tolerance on Distance Refractive Power (Progressive Addition Lenses) Cylinder Cylinder Sphere Meridian Power Tolerance on Sphere Cylinder Meridian Power ≥ 0.00 D > - 2.00 D (minus cylinder convention) > -3.50 D (minus cylinder convention) ≤ -2.00 D ≤ -3.50 D From -8.00 D to +8.00 D ± 0.16 D ± 0.16 D ± 0.18 D ± 5% Stronger than ±8.00 D ± 2% ± 0.16 D ± 0.18 D ± 5% 3. Tolerance on the direction of cylinder axis Nominal value of the ≥ 0.12 D > 0.25 D > 0.50 D > 0.75 D < 0.12 D > 1.50 D cylinder power (D) ≤ 0.25 D ≤ 0.50 D ≤ 0.75 D ≤ 1.50 D Tolerance of the axis Not Defined ° ° ° ° ° (degrees) ± 14 ± 7 ± 5 ± 3 ± 2 4. Tolerance on addition power for multifocal and progressive addition lenses Nominal value of addition power (D) ≤ 4.00 D > 4.00 D Nominal value of the tolerance on the addition power (D) ± 0.12 D ± 0.18 D 5. Tolerance on Prism Reference Point Location and Prismatic Power • The prismatic power measured at the prism reference point shall not exceed 0.33Δ or the prism reference point shall not be more than 1.0 mm away from its specified position in any direction. -

Hyperbolic Geometry

Hyperbolic Geometry David Gu Yau Mathematics Science Center Tsinghua University Computer Science Department Stony Brook University [email protected] September 12, 2020 David Gu (Stony Brook University) Computational Conformal Geometry September 12, 2020 1 / 65 Uniformization Figure: Closed surface uniformization. David Gu (Stony Brook University) Computational Conformal Geometry September 12, 2020 2 / 65 Hyperbolic Structure Fundamental Group Suppose (S; g) is a closed high genus surface g > 1. The fundamental group is π1(S; q), represented as −1 −1 −1 −1 π1(S; q) = a1; b1; a2; b2; ; ag ; bg a1b1a b ag bg a b : h ··· j 1 1 ··· g g i Universal Covering Space universal covering space of S is S~, the projection map is p : S~ S.A ! deck transformation is an automorphism of S~, ' : S~ S~, p ' = '. All the deck transformations form the Deck transformation! group◦ DeckS~. ' Deck(S~), choose a pointq ~ S~, andγ ~ S~ connectsq ~ and '(~q). The 2 2 ⊂ projection γ = p(~γ) is a loop on S, then we obtain an isomorphism: Deck(S~) π1(S; q);' [γ] ! 7! David Gu (Stony Brook University) Computational Conformal Geometry September 12, 2020 3 / 65 Hyperbolic Structure Uniformization The uniformization metric is ¯g = e2ug, such that the K¯ 1 everywhere. ≡ − 2 Then (S~; ¯g) can be isometrically embedded on the hyperbolic plane H . The On the hyperbolic plane, all the Deck transformations are isometric transformations, Deck(S~) becomes the so-called Fuchsian group, −1 −1 −1 −1 Fuchs(S) = α1; β1; α2; β2; ; αg ; βg α1β1α β αg βg α β : h ··· j 1 1 ··· g g i The Fuchsian group generators are global conformal invariants, and form the coordinates in Teichm¨ullerspace. -

Cross-Ratio Dynamics on Ideal Polygons

Cross-ratio dynamics on ideal polygons Maxim Arnold∗ Dmitry Fuchsy Ivan Izmestievz Serge Tabachnikovx Abstract Two ideal polygons, (p1; : : : ; pn) and (q1; : : : ; qn), in the hyperbolic plane or in hyperbolic space are said to be α-related if the cross-ratio [pi; pi+1; qi; qi+1] = α for all i (the vertices lie on the projective line, real or complex, respectively). For example, if α = 1, the respec- − tive sides of the two polygons are orthogonal. This relation extends to twisted ideal polygons, that is, polygons with monodromy, and it descends to the moduli space of M¨obius-equivalent polygons. We prove that this relation, which is, generically, a 2-2 map, is completely integrable in the sense of Liouville. We describe integrals and invari- ant Poisson structures, and show that these relations, with different values of the constants α, commute, in an appropriate sense. We inves- tigate the case of small-gons, describe the exceptional ideal polygons, that possess infinitely many α-related polygons, and study the ideal polygons that are α-related to themselves (with a cyclic shift of the indices). Contents 1 Introduction 3 ∗Department of Mathematics, University of Texas, 800 West Campbell Road, Richard- son, TX 75080; [email protected] yDepartment of Mathematics, University of California, Davis, CA 95616; [email protected] zDepartment of Mathematics, University of Fribourg, Chemin du Mus´ee 23, CH-1700 Fribourg; [email protected] xDepartment of Mathematics, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802; [email protected] 1 1.1 Motivation: iterations of evolutes . .3 1.2 Plan of the paper and main results . -

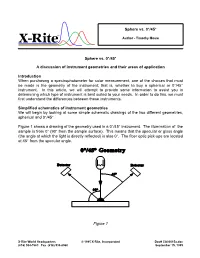

Sphere Vs. 0°/45° a Discussion of Instrument Geometries And

Sphere vs. 0°/45° ® Author - Timothy Mouw Sphere vs. 0°/45° A discussion of instrument geometries and their areas of application Introduction When purchasing a spectrophotometer for color measurement, one of the choices that must be made is the geometry of the instrument; that is, whether to buy a spherical or 0°/45° instrument. In this article, we will attempt to provide some information to assist you in determining which type of instrument is best suited to your needs. In order to do this, we must first understand the differences between these instruments. Simplified schematics of instrument geometries We will begin by looking at some simple schematic drawings of the two different geometries, spherical and 0°/45°. Figure 1 shows a drawing of the geometry used in a 0°/45° instrument. The illumination of the sample is from 0° (90° from the sample surface). This means that the specular or gloss angle (the angle at which the light is directly reflected) is also 0°. The fiber optic pick-ups are located at 45° from the specular angle. Figure 1 X-Rite World Headquarters © 1995 X-Rite, Incorporated Doc# CA00015a.doc (616) 534-7663 Fax (616) 534-8960 September 15, 1995 Figure 2 shows a drawing of the geometry used in an 8° diffuse sphere instrument. The sphere wall is lined with a highly reflective white substance and the light source is located on the rear of the sphere wall. A baffle prevents the light source from directly illuminating the sample, thus providing diffuse illumination. The sample is viewed at 8° from perpendicular which means that the specular or gloss angle is also 8° from perpendicular. -

Hyperbolic Geometry, Fuchsian Groups, and Tiling Spaces

HYPERBOLIC GEOMETRY, FUCHSIAN GROUPS, AND TILING SPACES C. OLIVARES Abstract. Expository paper on hyperbolic geometry and Fuchsian groups. Exposition is based on utilizing the group action of hyperbolic isometries to discover facts about the space across models. Fuchsian groups are character- ized, and applied to construct tilings of hyperbolic space. Contents 1. Introduction1 2. The Origin of Hyperbolic Geometry2 3. The Poincar´eDisk Model of 2D Hyperbolic Space3 3.1. Length in the Poincar´eDisk4 3.2. Groups of Isometries in Hyperbolic Space5 3.3. Hyperbolic Geodesics6 4. The Half-Plane Model of Hyperbolic Space 10 5. The Classification of Hyperbolic Isometries 14 5.1. The Three Classes of Isometries 15 5.2. Hyperbolic Elements 17 5.3. Parabolic Elements 18 5.4. Elliptic Elements 18 6. Fuchsian Groups 19 6.1. Defining Fuchsian Groups 20 6.2. Fuchsian Group Action 20 Acknowledgements 26 References 26 1. Introduction One of the goals of geometry is to characterize what a space \looks like." This task is difficult because a space is just a non-empty set endowed with an axiomatic structure|a list of rules for its points to follow. But, a priori, there is nothing that a list of axioms tells us about the curvature of a space, or what a circle, triangle, or other classical shapes would look like in a space. Moreover, the ways geometry manifests itself vary wildly according to changes in the axioms. As an example, consider the following: There are two spaces, with two different rules. In one space, planets are round, and in the other, planets are flat. -

A Historical Introduction to Elementary Geometry

i MATH 119 – Fall 2012: A HISTORICAL INTRODUCTION TO ELEMENTARY GEOMETRY Geometry is an word derived from ancient Greek meaning “earth measure” ( ge = earth or land ) + ( metria = measure ) . Euclid wrote the Elements of geometry between 330 and 320 B.C. It was a compilation of the major theorems on plane and solid geometry presented in an axiomatic style. Near the beginning of the first of the thirteen books of the Elements, Euclid enumerated five fundamental assumptions called postulates or axioms which he used to prove many related propositions or theorems on the geometry of two and three dimensions. POSTULATE 1. Any two points can be joined by a straight line. POSTULATE 2. Any straight line segment can be extended indefinitely in a straight line. POSTULATE 3. Given any straight line segment, a circle can be drawn having the segment as radius and one endpoint as center. POSTULATE 4. All right angles are congruent. POSTULATE 5. (Parallel postulate) If two lines intersect a third in such a way that the sum of the inner angles on one side is less than two right angles, then the two lines inevitably must intersect each other on that side if extended far enough. The circle described in postulate 3 is tacitly unique. Postulates 3 and 5 hold only for plane geometry; in three dimensions, postulate 3 defines a sphere. Postulate 5 leads to the same geometry as the following statement, known as Playfair's axiom, which also holds only in the plane: Through a point not on a given straight line, one and only one line can be drawn that never meets the given line.