The Last Hours (Chain of Gold

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perth Music Interviews Ben Stewart (Filmmaker) Amber Flynn

Perth Music Interviews Ben Stewart (Filmmaker) Amber Flynn (Rabbit Island) Sean O’Neill (Hang on Saint Christopher) Bill Darby David Craddock (Davey Craddock and the Spectacles) Scott Tomlinson (Kill Teen Angst) Thomas Mathieson (Mathas) Joe Bludge (The Painkillers) Tracey Read (The Wine Dark Sea) Rob Schifferli (The Leap Year) Chris Cobilis Andy Blaikie by Benedict Moleta December 2011 This collection of interviews was put together over the course of 2011. Some of these people have been involved in music for ten years or more, others not so long. The idea was to discuss background and development, as well as current and long-term musical projects. Benedict Moleta [email protected] Ben Stewart (Filmmaker) Were you born in Perth ? Yeah, I was born in Mt Lawley. You've been working on a music documentary for a while now, what's it about ? I started shooting footage mid 2008. I'm making a feature documentary about a bunch of bands over a period of time, it's an unscientific longitudinal study of sorts. It's a long process because I want to make an observational documentary with the narrative structure of a fiction film. I'm trying to capture a coming of age cliché but character arcs take a lot longer in real life. I remember reading once that rites of passage are good things to structure narratives around, so that's what I'm going to do, who am I to argue with a text book? Fair call. I guess one of the characteristics of bands developing or "coming of age" is that things can emerge, change, pass away and be reconfigured quickly. -

Liam Gallagher Til Oslo Spektrum!

03-04-2018 10:02 CEST LIAM GALLAGHER TIL OSLO SPEKTRUM! Tidligere Oasis og Beady Eye-vokalist Liam Gallagher gjester Oslo Spektrum 29. november! Den britiske artisten er aktuell med sitt første soloalbum «As You Were». Billetter i salg fredag 6. april kl. 10.00. Liam ble født i Manchester i 1972, og er den yngste av tre brødre. Som ung viste han lite interesse for musikk, men i tenårene begynte han å høre på band som The Beatles, The Who, The Stone Roses og The Kinks. Det var også da han opparbeidet seg sin fasinasjon og beundring av John Lennon, som han senere har oppkalt sin sønn etter. Gallagher slo gjennom sammen med sin bror Noel i britpop-bandet Oasis på 90-tallet, og står bak velkjente låter som «Wonderwall» og «Don’t Look Back in Anger». Etter dette fortsatte han sin karriere som vokalist i Beady Eye, men bandet ble oppløst i 2014. Mange vil anerkjenne Liam som den beste frontmannen og vokalisten fra sin generasjon, og en av de mest gjenkjennelige karakterene innenfor moderne britisk musikk. I 2017 slapp han sitt første soloalbum «As You Were», som debuterte som nummer 1 på den britiske albumlista. Allmusic var meget begeistret og beskriver musikken slik: «As You Were doesn't sound retro even though it is, in essence, a throwback to a throwback -- a re-articulation of Liam's '90s obsession with the '60s.» The Daily Mirror mener «As You Were' is the legendary rocker at his very best». Vi gleder oss enormt til å oppleve Liam Gallagher live i Oslo! Live Nation Norge er landets største konsertarrangør. -

Beady Eye the Beat Goes on Mp3, Flac, Wma

Beady Eye The Beat Goes On mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: The Beat Goes On Country: UK Released: 2011 Style: Rock & Roll MP3 version RAR size: 1613 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1781 mb WMA version RAR size: 1588 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 641 Other Formats: AU DTS DMF MP4 MP2 ADX FLAC Tracklist A The Beat Goes On B In The Bubble With A Bullet Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Beady Eye Records Ltd. Copyright (c) – Beady Eye Records Ltd. Designed At – Intro Credits Artwork [Art] – House* Mixed By – Beady Eye, Jonathan Shakhovskoy (tracks: A) Producer – Beady Eye, Steve Lillywhite (tracks: A) Written-By – Bell*, Archer*, Gallagher* Notes Glossy flip-back sleeve. ⓟ & © 2011 Beady Eye Records Ltd Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 5 052670006078 Matrix / Runout (Side A): BEADY 6 A1 Matrix / Runout (Side B): BEADY 6 B1 Rights Society: MCPS Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Beady The Beat Goes On (7", Beady Eye BEADY6 BEADY6 UK 2011 Eye Single, Ltd, Num) Records The Beat Goes On (Radio Beady Beady Eye BEADYSCD6P Edit) (CD, Single, BEADYSCD6P UK 2011 Eye Records Promo) Beady The Beat Goes On (7", Beady Eye BEADY6 BEADY6 UK 2011 Eye Single, TP, W/Lbl) Records Beady The Beat Goes On (File, Dangerbird none none US 2011 Eye AAC, Single, 256) Records Related Music albums to The Beat Goes On by Beady Eye Beady Eye - Second Bite Of The Apple Beady Eye - Different Gear, Still Speeding Beady Belle - Moderation Beady Eye - The Roller Beady Belle - CEWBEAGAPPIC Beady Belle - When My Anger Starts To Cry Beady Eye - Beady Eye Beady Eye - Four Letter Word Beady Eye - Bring The Light Beady Eye - Be. -

Crowd Safety Presentation

Human Behaviour and Crowd Consideraons in Normal and Emergency Condions Presented by Steve Allen FdA MIFireE FIIRSM MIFSM [email protected] www.crowdsafety.org Steve Allen FdA MIFireE FIIRSM MIFSM • 25 Years Crowd and Event Safety Experience ‘Normal and Emergency’ • Degree Crowd and Safety Management • Chartered Health and Safety Consultant • Occupaonal Safety and Health Consultants Register – Registered Consultant • Chartered Fire Safety Consultant • Former Royal Navy Fire-Fighter • Former Director of Security and Safety: Oasis, Eminem, Red Hot Chilli Peppers, Kasabian, Rolling Stones (UK Only), Bease Boys, Led Zeppelin, Shakira, Stereophonics, Dixie Chicks, Beady Eye • Retail Sector, Various Events, Venues, FesFval’s and other Major Events worldwide including Motorsports, Royal Events, Fireworks and events of significant importance • Purple Guide – Acknowledged Contributor • Australian live Performance – Author of the Audience Safety Chapter • Event Working Party for US Technical Standards version of the Purple Guide • Managing Crowds Safely (HSG 154) – Reviewed 2016 for UKCMA • Pioneer of the “Showstop Procedure” (Globally used now and recognised by HSE) • Guest Speaker and Trainer worldwide on event safety, crowds, human behaviour and fire safety • Fire Risk Assessor for leisure, event and retail industry’s www.crowdsafety.org Terrorism Crowded Spaces www.crowdsafety.org Some Crowd Disasters last 6 years • 2016: - 50 – 600 Dead Stampede Ethiopia • 2015: - 2442 Dead & 1028 injured • 2014: - 106 Dead & 262 Injured • 2013: - 470 Dead & 757 injured www.crowdsafety.org Why do crowd crushes happen? • We are trying to service more people in less Fme…. • Too many people in too liele space • Bolenecks • Poor Planning • Site Design • Informaon • Management • Inexperience and lack of competence of organisers assessors • Terrorism www.crowdsafety.org 3 Primary Reasons to prevent • Moral • Legal • Financial www.crowdsafety.org Manchester United Evacuaon • The blunder is set to cost United £3 million as it is forced to shell out to disappointed fans. -

James Dyer CV

www.jamesdyer.co SUZ CRUZ 01932 252577 COMMERCIALS Company Product Director Producer Fat Lemon Smart Energy GB “Smart Meter” Chris Faith Cabell Hopkins Marshmallow Laser Feast VW Passat Barney Steel Mark Lougue Tangerine Films Canon Project M Mark Rodway Esteban Frost Nonsense MoneyGram “The Gift Of Cricket” Mathew Losasso Neil Horner Hobby Films Carphone Warehouse “Colour Invasion” Magnus Renfors Erik Liss Found Hiscox “The House I Grew Up In” Mike Sharpe Sean Stuart Not To Scale Price Waterhouse Cooper 5x Films Nathan Princer Scott O’Donnell US London Vashi “Behind The Scenes” Jo Tanner/Mark Howard Gail Mosley Minimart Rubicon “Mango” Mehaj Huda Leo Rowbotham Minimart Sudocrem "Care & Protect" Ornette Spencely Nikki Chapman Bare Films Wiltshire Farm Foods “ Betsan Morris Evans Kelly Doyle Academy Talk Talk “Christmas” Us Dom Thomas Academy Canon “Christmas Sculpture” Conkerco Mark Whittow-Williams Academy Mother 2 Mothers Martin De Thurah Dom Thomas & Simon Cooper The Outfit Lloyds ""Home", "Business" Southan Morris Debbie Impett Friend Asda George “Back to School” Georgie Banks-Davies Mikey Levelle Academy Talk Talk Idents Us Mark Whittow-Williams A-Vision Arm & Hammer Andrew Smith Carlos Downie BSKYB The Face “Ftr Naomi Campbell” Phil Griffin Grant Branton Prettybird River Island Brewer Claire Luke Minimart Sudocrem “For All Of Lifes Little Dramas” Beverley Fortnum Nikki Chapman Red Bee Media Radio 1 "Big Weekend" The General Assembly Ann-Marie Small Skin Flicks Blink Box “Dangerous” The General Assembly Chris Massey Jack Morton Worldwide -

Miles Kane Bio 2012

Miles Kane Dubbed “one of Britain’s landmark composers” by MOJO, 26-year-old intrepid rock ‘n’ roller Miles Kane has gone from selling out Water Rats to winning over crowds at major UK and international festivals. Dapper of suit and young Macca of hair, he’s been capturing the nation’s hearts, souls and minds since May 2011, after storming the scene with acclaimed solo debut ‘Colour of the Trap’. One of the biggest selling debut LPs of that year – and one which would curry favour with critics and fans alike – it cemented Miles’ fate as a new British musical institution. Produced by Dan Carey in South London and Dan the Automator in San Francisco – to give his rhythm tracks a hip hop undertow – the album earned him endless plaudits – including 4* reviews from the NME, The Times, The Independent, the Guardian, Q and MOJO – and peaked at No.11 in the UK Charts. He became one of 2011’s success stories, nominated for Breakthrough Act at the MOJO Awards that year, and for Best Solo Artist at the NME awards 2012, as well selling out two headline tours and providing special guest support to Beady Eye, Kasabian and the Arctic Monkeys at their momentous hometown Don Valley Bowl shows. But now let’s dip into the recent past. Aged 18, Kane was a member of The Little Flames. In 2007, from the embers of that band he formed The Rascals. He first met Alex Turner when The Rascals supported the Sheffield four-piece the same year. He spent most of 2008 playing and touring with the Arctic Monkeys frontman as The Last Shadow Puppets, in support of their Mercury-nominated album ‘The Age Of The Understatement’. -

Gallagher Claims Liam Quit Beady Eye by Text Message

24 Friday Friday, December 21, 2018 Lifestyle | Gossip Gallagher claims Liam quit Beady Eye by text message iam Gallagher quit Beady Eye by text message, his estranged Man, he didn’t even have the balls to phone his bandmates. Because brother Noel Gallagher has claimed. The ‘Greedy Soul’ he got a solo deal, it was, See you later, lads. Then when he got his Lsinger formed the band with the other remaining members deal with Live Nation, no one was telling him, ‘Don’t do any Oasis of Oasis - Gem Archer, Andy Bell and Chris Sharrock - after Noel songs, do your new stuff, that’s what your good at.’ “ Once he knew quit the group in August 2009 following a backstage bust-up be- that Beady Eye was finished Noel had no hesitation in welcoming tween the brothers before a headline appearance at a Paris music Gem and Chris into his group and the timing was perfect because festival. Beady Eye disbanded in October 2014 after releasing two two of his members had decided to quit the High Flying Birds the albums, ‘Different Gear, Still Speeding’ and ‘BE’, and now guitarist same year. The rock legend said: “When I first started [as a solo Gem and drummer Chris play in Noel’s touring band the High Fly- artist], I had Tim [Smith, guitar] and Jeremy [Stacey, drums], and ing Birds. The ‘Wonderwall’ songwriter has accused Liam of not the great thing about session musicians is that when you’re not having the guts to tell his friends he was walking away from the sure what you’re doing, they’re bang on it, they make it sound like group to their faces or even in a phone call and instead sent them the record. -

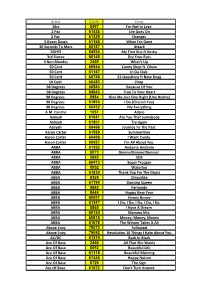

Karaoke List

Artist Code Song 10cc 8497 I'm Not In Love 2 Pac 61426 Life Goes On 2 Pac 61425 Changes 3 Doors Down 61165 When I'm Gone 30 Seconds To Mars 60147 Attack 3OH!3 84954 My First Kiss ft Kesha 3rd Storee 60145 Dry Your Eyes 4 Non Blondes 2459 What's Up 50 Cent 60944 Candy Shop ft. Olivia 50 Cent 61147 In Da Club 50 Cent 60748 21 Questions ft Nate Dogg 50 Cent 60483 Pimp 98 Degrees 60543 Because Of You 98 Degrees 84943 True To Your Heart 98 Degrees 8984 Give Me Just One Night (Una Noche) 98 Degrees 61890 I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees 60332 My Everything A.M. Canche 1051 Adoro Aaliyah 61681 Are You That Somebody Aaliyah 61801 Try Again Aaliyah 60468 Journey To The Past Aaron Carter 61588 Summertime Aaron Carter 60458 I Want Candy Aaron Carter 60557 I'm All About You ABBA 61352 Andante Andante ABBA 8073 Gimme!Gimme!Gimme! ABBA 2692 SOS ABBA 60413 Super Trooper ABBA 8952 Waterloo ABBA 61830 Thank You For The Music ABBA 8369 Chiquitita ABBA 61199 Dancing Queen ABBA 8842 Fernando ABBA 8444 Happy New Year ABBA 60001 Honey Honey ABBA 61347 I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do ABBA 8865 I Have A Dream ABBA 60134 Mamma Mia ABBA 60818 Money, Money, Money ABBA 61678 The Winner Takes It All Above Envy 79073 Followed Above Envy 79092 Revolution 10 Things I Hate About You AC/DC 61319 Back In Black Ace Of Base 2466 All That She Wants Ace Of Base 8592 Beautiful Life Ace Of Base 61118 Beautiful Morning Ace Of Base 61346 Happy Nation Ace Of Base 8729 The Sign Ace Of Base 61672 Don't Turn Around Acid House Kings 61904 This Heart Is A Stone Acquiesce 60699 Oasis Adam -

Repertorio Di Nicola Gori Al 29/05/2020

Repertorio di Nicola Gori al 29/05/2020: DAMON ALBARN Apple carts Dying isn’t easy Everyday robot Heavy seas of love Sunset coming on BEADY EYE Off at the next exit Start anew The roller BLUR Battery in your leg Beetlebum Caravan Charmless man Coffee and tv End of a century Girls and boys Good song Miss America New world towers No distance left to run Out of time Song 2 Sweet song Tender The universal This is a low DAVID BOWIE After all All the young dudes An occasional dream Ashes to ashes Can’t help thinking about me Changes China girl Cracked actor Dodo Eight line poem Fame Five years Heroes Kooks Letter to Hermione Life on Mars? Looking for water Repertorio di Nicola Gori al 29/05/2020 - Pag.1 di 7 Memory of a free festival Modern love Moonage daydream New killer star Oh! You pretty things Quicksand Ragazzo solo, ragazza sola (testo di Mogol in italiano di “Space oddity”) Rebel rebel Seven Something in the air Space oddity Starman Survive The Bewlay brothers The man who sold the world The wild eyed boy from freecloud Time Where are we now Ziggy Stardust JACQUES BREL & MORT SCHUMAN My death EDIE BRICKELL AND THE NEW BOHEMIANS What I am BUFFALO SPRINGFIELD For what it’s worth J.J.CALE Cocaine LUCA CARBONI Bologna è una regola Luca lo stesso RICCARDO COCCIANTE A mano a mano LEONARD COHEN Hallelujah PAOLO CONTE Via con me GRAHAM COXON All over me STEVE CROPPER & EDDIE FLOYD Knock on wood Repertorio di Nicola Gori al 29/05/2020 - Pag.2 di 7 FRANCESCO DE GREGORI Generale Il bandito e il campione La donna cannone DEPECHE MODE Freelove Heaven Precious BOB DYLAN Blowin’ in the wind Hurricane Jokerman Knocking on heaven’s door Like a rolling stone Mr. -

Live Forever : Collecting Live Art Pdf, Epub, Ebook

LIVE FOREVER : COLLECTING LIVE ART PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Teresa Calonje | 204 pages | 23 Jun 2015 | Verlag Der Buchhandlung Walther Konig | 9783863355807 | English | Cologne, Germany Live Forever : Collecting Live Art PDF Book Mummy Cartonnage of a Woman. HITE Collection. Tags: oasis, liam gallagher, liam gallagher, liam, wonderwall, noel, noel gallagher, 90s, britpop, manchester, live forever, definitely maybe, be here now, indie, british, whats the story morning glory, brit pop, guitar, high flying birds, nineties, n roll, vintage, space, supersonic, half the world away, beady eye, as you were. Poster By Taylorroom Edited by Valerio Terraroli. Zoom will also automatically prompt you to install when your join your first Zoom meeting. Tags: frank moth, vintage, retro, collage, digital collage, surrealism, planes, man, him, manhood, car, cars, floral, botanical, flowers, green, blue, blueprints, robots, leaves, red, black, s, s, pop art. Tags: one piece, franky, straw hat crew, ciurma cappello di paglia, live forever, live forever industries. Foreword by Adrian Hearthfield. What about photography as art? The accompanying catalogue is supported by a Brooklyn Museum publications endowment established by the Iris and B. This hit really deeply. The increasing representation of trans identity throughout art and popular culture in recent years has been nothing if not paradoxical. This event is for Ambassadors and Clients. The seller is responsible for the transfer fee. Though Nefer-her apparently could not afford a stone vessel, he commissioned an artist to paint this jar to imitate granite. What will photography do, as it is added to this numb state oversaturated with images? Save on Nonfiction Trending price is based on prices over last 90 days. -

RAR Newsletter 111109.Indd

RIGHT ARM RESOURCE UPDATE JESSE BARNETT [email protected] (508) 238-5654 www.rightarmresource.com www.facebook.com/rightarmresource 11/9/2011 Mike Doughty & Rosanne Cash “Holiday (What Do You Want?)” The perfect new holiday song for Triple-A, from Mike’s album Yes And Also Yes Going for holiday adds on Monday Added early at WFPK National tour now: 11/11 Minneapolis, 11/12 Chicago, 11/13 Cleveland, 11/15 Boston... “Na Na Nothing” is New & Active and reached top 7 on the Indicator chart and top 5 on the FMQB Public chart Ben Folds Five “House” The first new Ben Folds Five track in 11 years, from the Ben Folds retrospective album The Best Imitation Of Myself New: WNRN, KCLC, WMWV Already ON: KCMP, WXPN, WYEP, WMVY, WFIV, KMTN, WYCE, KFMU, KSPN, WEXT, WBSD, WUKY, WHRV, KDHX, WCBE, WERU Single disc and three disc set in stores now Ben is writing a new BFF album now John Hiatt “Adios To California” Most Added again! New: KCSN, WEXT, KSUT, WMVY, KDBB, KTAO, KMTN, WKZE, WBSD ON: KINK, KRSH, KPND, WZEW, WFUV, WFPK, WNRN, WBJB, KOZT, KOHO, KNBA, WYCE, DMX, Music Choice, WOCM, WERS, WDST... On tour now “‘Adios to California’ strings together telling couplets about a break-up that should be the envy of every novelist.” - Chicago Tribune Graffiti 6 “Free” Building quickly! BDS Monitored 23*! Indicator 24*! FMQB Public 43*! New: WDST, KUT ON: KBCO, KMTT, WXRV, KINK, CIDR, WMMM, WQKL, KCKC, WCLZ, WNCS, KRVB, WNWV, KTHX, KRSH, WCOO, KCSN, Music Choice... EP (out now) features many stripped down tracks, full cd Colours in January Brand new video online now Peter Gabriel - New Blood (album) New: KDBB, WUTC, WSYC ON: Sirius Spectrum, WFUV, KCMP, KCRW, WEHM, KUT, KTBG, WNCW, WMVY, WMWV, WVMP, KOZT, WBJB, WWCT, WFIV, KSUT, KOHO, KSKI, WEXT, WYCE, Acoustic Cafe.. -

Pride Student Newspaper of Penn State New Kensington

The nittany pride Student Newspaper of Penn State New Kensington Vol. V No. 2 nittanypride.wordpress.com February 2011 Diversity Diversity - “Be Proud of Who You Are” ------------------------------------ Superbowl Halftime Show Needs To Go ------------------------------------ MTV Bares All in the New Hit Show “Skins” ------------------------------------ It’s the End of the Net As We Know It ------------------------------------ Pluto: Not a Planet or a Good Role Model For Children Table of ConTenTs Alumnus Vera Spina Recalls “Glory Days at PSNK”............................................. Page 2 GIG Club at PSNK Experiments With New Direction........................................... Pages 3-4 Diversity – “Be Proud of Who You Are”............................................................. Pages 5-6 Martial Arts & Self Defense Club Presentation at Cafe 780.................................. Page 7 Super Bowl Halftime Show Needs to Go........................................................... Page 8 Dirty Hits & Double Standards........................................................................ Page 9 MTV Bares All in the New Hit Show “Skins”....................................................... Page 10 Beady Eye: Different Name, Same Sound........................................................ Page 11 “We Hope You Have Enjoyed the Show”........................................................... Page 12 Arnold Schools Require More Funding.............................................................. Page 13 Domestic Violence: Public