Transcript of Oral History Interview with Osman Ahmed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redox DAS Artist List for Period

Page: Redox D.A.S. Artist List for01.10.2020 period: - 31.10.2020 Date time: Title: Artist: min:sec 01.10.2020 00:01:07 A WALK IN THE PARK NICK STRAKER BAND 00:03:44 01.10.2020 00:04:58 GEORGY GIRL BOBBY VINTON 00:02:13 01.10.2020 00:07:11 BOOGIE WOOGIE DANCIN SHOES CLAUDIAMAXI BARRY 00:04:52 01.10.2020 00:12:03 GLEJ LJUBEZEN KINGSTON 00:03:45 01.10.2020 00:15:46 CUBA GIBSON BROTHERS 00:07:15 01.10.2020 00:22:59 BAD GIRLS RADIORAMA 00:04:18 01.10.2020 00:27:17 ČE NE BOŠ PROBU NIPKE 00:02:56 01.10.2020 00:30:14 TO LETO BO MOJE MAX FEAT JAN PLESTENJAK IN EVA BOTO00:03:56 01.10.2020 00:34:08 I WILL FOLLOW YOU BOYS NEXT DOOR 00:04:34 01.10.2020 00:38:37 FEELS CALVIN HARRIS FEAT PHARRELL WILLIAMS00:03:40 AND KATY PERRY AND BIG 01.10.2020 00:42:18 TATTOO BIG FOOT MAMA 00:05:21 01.10.2020 00:47:39 WHEN SANDRO SMILES JANETTE CRISCUOLI 00:03:16 01.10.2020 00:50:56 LITER CVIČKA MIRAN RUDAN 00:03:03 01.10.2020 00:54:00 CARELESS WHISPER WHAM FEAT GEORGE MICHAEL 00:04:53 01.10.2020 00:58:49 WATERMELON SUGAR HARRY STYLES 00:02:52 01.10.2020 01:01:41 ŠE IMAM TE RAD NUDE 00:03:56 01.10.2020 03:21:24 NO ORDINARY WORLD JOE COCKER 00:03:44 01.10.2020 03:25:07 VARAJ ME VARAJ SANJA GROHAR 00:02:44 01.10.2020 03:27:51 I LOVE YOU YOU LOVE ME ANTHONY QUINN 00:02:32 01.10.2020 03:30:22 KO LISTJE ODPADLO BO MIRAN RUDAN 00:03:02 01.10.2020 03:33:24 POROPOMPERO CRYSTAL GRASS 00:04:10 01.10.2020 03:37:31 MOJE ORGLICE JANKO ROPRET 00:03:22 01.10.2020 03:41:01 WARRIOR RADIORAMA 00:04:15 01.10.2020 03:45:16 LUNA POWER DANCERS 00:03:36 01.10.2020 03:48:52 HANDS UP / -

Detention in Afghanistan and Guantánamo

Composite statement: Detention in Afghanistan and Guantanamo Bay Shafiq Rasul, Asif Iqbal and Rhuhel Ahmed 1. All three men come from Tipton in West Midlands, a poor area with a small community of Pakistani and Bangladeshi origin. The school all three attended is considered one of the worst in England. Rhuhel Ahmed and Asif Iqbal who are now both aged 22 were friends from school, although one year apart. Neither was brought up religiously but each was drawn towards Islam. Shafiq Rasul is now aged 27 and had a job working at the electronics store, Currys. He was also enrolled at the University of Central England. 2. This statement jointly made by them constitutes an attempt to set out details of their treatment at the hands of UK and US military personnel and civilian authorities during the time of their detention in Kandahar in Afghanistan in late December 2001 and throughout their time in American custody in Guantanamo Bay Cuba. This statement is a composite of the experiences of all 3. They are referred to throughout by their first names for brevity. There is far more that could be said by each, but that task is an open-ended one. They have tried to include the main features. 1 Detention in Afghanistan 3. All three men were detained in Northern Afghanistan on 28 November 2001 by forces loyal to General Dostum. They were loaded onto containers and transported to Sherbegan prison. The horrors of that transportation are well documented elsewhere and are not described in detail here. 4. According to information all three were given later, there were US forces present at the point they were packed into the containers together with almost 200 others. -

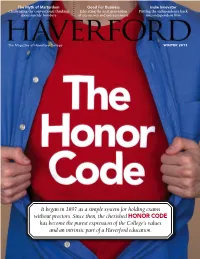

It Began in 1897 As a Simple System for Holding Exams Without Proctors

The Myth of Martyrdom Good For Business Indie Innovator Challenging the conventional thinking Educating the next generation Putting the independence back about suicide bombers of executives and entrepreneurs into independent film The Magazine of Haverford College WINTER 2013 It began in 1897 as a simple system for holding exams without proctors. Since then, the cherished HONOR CODE has become the purest expression of the College’s values and an intrinsic part of a Haverford education. 9 20 Editor Contributing Writers DEPARTMENTS Eils Lotozo Charles Curtis ’04 Prarthana Jayaram ’10 Associate Editor Lini S. Kadaba 2 View from Founders Rebecca Raber Michelle Martinez 4 Letters to the Editor Graphic Design Alison Rooney Tracey Diehl, Louisa Shepard 6 Main Lines Justin Warner ’93 Eye D Communications 15 Faculty Profile Assistant Vice President for Contributing Photographers College Communications Thom Carroll 20 Mixed Media Chris Mills ’82 Dan Z. Johnson Brad Larrison 25 Ford Games Vice President for Josh Morgan 48 Roads Taken and Not Taken Institutional Advancement Michael Paras Michael Kiefer Josh Rasmussen 49 Giving Back/Notes From Zachary Riggins the Alumni Association 54 Class News 65 Then and Now On the cover: Photo by Thom Carroll Back cover photo: Courtesy of Haverford College Archives The Best of Both Worlds! Haverford magazine is now available in a digital edition. It preserves the look and page-flipping readability of the print edition while letting you search names and keywords, share pages of the magazine via email or social networks, as well as print to your personal computer. CHECK IT OUT AT haverford.edu/news/magazine.php Haverford magazine is printed on recycled paper that contains 30% post-consumer waste fiber. -

Floor Debate March 10, 2016

Transcript Prepared By the Clerk of the Legislature Transcriber's Office Floor Debate March 10, 2016 [LB447A LB447 LB698A LB698 LB704 LB710 LB722 LB745 LB768 LB830 LB857 LB874 LB881 LB897 LB919 LB919A LB934A LB934 LB935 LB1003 LB1009 LB1022 LB1032 LB1073 LB1082 LB1082A LB1094 LR415 LR455 LR475 LR476] SPEAKER HADLEY PRESIDING SPEAKER HADLEY: GOOD MORNING, LADIES AND GENTLEMEN. WELCOME TO THE GEORGE W. NORRIS LEGISLATIVE CHAMBER FOR THE FORTY-FIRST DAY OF THE ONE HUNDRED FOURTH LEGISLATURE, SECOND SESSION. OUR CHAPLAIN FOR TODAY IS SENATOR LINDSTROM. PLEASE RISE. SENATOR LINDSTROM: (PRAYER OFFERED.) SPEAKER HADLEY: THANK YOU, SENATOR LINDSTROM. I CALL TO ORDER THE FORTY-FIRST DAY OF THE ONE HUNDRED FOURTH LEGISLATURE, SECOND SESSION. SENATORS, PLEASE RECORD YOUR PRESENCE. ROLL CALL. MR. CLERK, PLEASE RECORD. CLERK: I HAVE A QUORUM PRESENT, MR. PRESIDENT. SPEAKER HADLEY: THANK YOU, MR. CLERK. ARE THERE ANY CORRECTIONS FOR THE JOURNAL? CLERK: I HAVE NO CORRECTIONS. SPEAKER HADLEY: THANK YOU. ARE THERE ANY MESSAGES, REPORTS, OR ANNOUNCEMENTS? CLERK: THE LOBBY REPORT AS REQUIRED BY LAW TO BE ACKNOWLEDGED IN THE JOURNAL, MR. PRESIDENT. I ALSO HAVE A SERIES OF AGENCY REPORTS THAT HAVE BEEN RECEIVED AND ARE AVAILABLE FOR MEMBER REVIEW ON THE LEGISLATIVE WEB SITE. THAT'S ALL THAT I HAD, MR. PRESIDENT. (LEGISLATIVE JOURNAL PAGES 937-938.) SPEAKER HADLEY: THANK YOU, MR. CLERK. WE WILL PROCEED TO THE FIRST ITEM ON THE AGENDA. 1 Transcript Prepared By the Clerk of the Legislature Transcriber's Office Floor Debate March 10, 2016 CLERK: MR. PRESIDENT, A BILLS THIS MORNING. LB698, IT'S A BILL BY SENATOR MELLO. -

Late Autumn 2018

MIND MOON CIRCLE Journal of the Sydney Zen Centre Very Late Autumn 2018 oh dear beginner ... Mind Moon Circle: Winter/Spring edition The next edition of Mind Moon Circle, will be exploring the theme Resonance. The great Japanese poem, The Take of the Heike, begins, The tolling of the great bell of the Gion temple resonates with the insubstantiality of all things. Bells point us in the direction of Awakening and Resonance illuminates the bodhisattva path. At his recent transmission, Allan Marett was given the name, Resonant Cloud (Kyô-un) But bells are important in many other contexts: in various parts of the world, bells mark the location of animals; bells are central to music; there are the school bells of our childhood; the bells that mark the passage of time. And things resonate not just in the world of sound, but also within the mind. Allan’s transmission teisho on Yunmen’s Golden Wind, which will be published in this edition, explores resonances between Aboriginal Law and the Dharma. Let your creative bells ring forth and let us know what Resonance means for you. Please send your poems, stories and artwork to co-editors: Jillian Ball: [email protected] Janet Selby: [email protected] by October 7th 2018. Temple bells die out. The fragrant blossoms remain. A perfect evening. Matsuo Basho 2 ere is the Autumn edition of our MMC journal. You may have noticed, I am referring to it as Very Late Autumn 2018. I apologise for blending Autumn into Winter. Things just got in The Way. Never - the - less it is here. -

Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman!" Adventures of a Curious Character by Richard P

"Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman!" Adventures of a Curious Character by Richard P. Feynman as told to Ralph Leighton Preface The stories in this book were collected intermittently and informally during seven years of very enjoyable drumming with Richard Feynman. I have found each story by itself to be amusing, and the collection taken together to be amazing: That one person could have so many wonderfully crazy things happen to him in one life is sometimes hard to believe. That one person could invent so much innocent mischief in one life is surely an inspiration! RALPH LEIGHTON Introduction I hope these won't be the only memoirs of Richard Feynman. Certainly the reminiscences here give a true picture of much of his character--his almost compulsive need to solve puzzles, his provocative mischievousness, his indignant impatience with pretension and hypocrisy, and his talent for one-upping anybody who tries to one-up him! This book is great reading: outrageous, shocking, still warm and very human. For all that, it only skirts the keystone of his life: science. We see it here and there, as background material in one sketch or another, but never as the focus of his existence, which generat ions of his students and colleagues know it to be. Perhaps nothing else is possible. There may be no way to construct such a series of delightful stories about himself and his work: the challenge and frustration, the excitement that caps insight, the deep pleasure of scientific understanding that has been the wellspring of happiness in his life. -

Guida a Eurovision: Europe Shine a Light

La prima volta dell’Eurovision Song Contest annullato L’edizione 2020 dell’Eurovision Song Contest non andrà in scena. Era in programma il 12, 14 e 16 maggio alla Ahoy Arena di Rotterdam, nei Paesi Bassi, ma la pandemia da Coronavirus che partendo dalla Cina ha coinvolto prima l’Italia, poi tutta Europa ed il resto del Mondo, ha portato l’EBU e la tv pubblica olandese all’unica decisione possibile: cancellare la manifestazione per quest’anno. Non è mai successo, nella storia del concorso, che sia saltata un'edizione, nemmeno quando problemi tecnici ed economici, in passato, ne avevano messo in forte dubbio lo svolgimento. Una decisione sofferta, ovviamente, perché i motori erano già caldi e la messa a punto dell’area, con la costruzione del palco, era ormai prossima; tanti i fan lasciati delusi. L’EBU ha spiegato che non sarebbe stato possibile mettere in pratica nessuna delle altre ipotesi: uno show da remoto, oltre a causare evidenti squilibri tecnici fra i vari paesi, non avrebbe avuto lo stesso appeal dell’evento, fortemente aggregativo. Per gli stessi motivi è stata scartata l’idea di andare in onda senza pubblico, mentre un rinvio a settembre o in un qualunque altro mese, oltre a dare meno tempo alla tv vincitrice per organizzare l’edizione 2021, non avrebbe comunque garantito lo svolgimento dell’evento vista l’evoluzione imprevedibile della pandemia. Allo stesso tempo, l’EBU ha dato parere favorevole alla designazione per l’Eurovision 2021 degli stessi interpreti scelti per il 2020: non tutte le emittenti hanno fatto questa scelta. Tutte le canzoni invece dovranno essere nuove, perché resta valida la regola per la quale i brani non devono essere stati pubblicati antecedentemente al 1° settembre dell’anno precedente all’edizione. -

Your Debt Elimination

YOUR DEBT ELIMINATION Your Debt Elimination Table of Contents Start Now 4 Let’s Transform You 4 How This System Manual Is Organized 5 The Four Keys to YOUR DEBT ELIMINATION Success 6 Make the Commitment 7 Frequently Asked Questions About Getting Started 8 Whose Wealth Is It? 10 Who’s Teaching Us How to Use Our Money? 10 The Forces at Work Against Your Financial Success 11 Who’s Scripting Your Dreams? 12 Keeping Up with the Jones Is Insane! 15 Why Get Debt-Free? 16 Till Debt Do Us Part 19 Credit…Your Financial Enemy... 21 Why Are We Obsessed with Using Credit? 21 Dis-Card Your Debt 22 Operate on a 100 Percent CASH Basis 25 How Credit Really Affects You 27 Using Credit Actually Lowers Your Standard of Living 28 A New Financial Attitude 29 New Seeds 29 The Three Stages of Transforming 29 What’s It Like to Operate on Cash? 31 The Monthly Payment Trap 32 Got Change? 37 Debt-Elimination System 40 The Cascading Debt-Elimination System 40 When Will You Be Completely Debt-FREE? 41 Page 1 of 185 YOUR DEBT ELIMINATION Let’s Get Down to Paying Off Your Debts 44 Watch the Power of Mathematics Working for You 47 Frequently Asked Questions About Debt-Elimination 51 Your Margin ™ 56 Creating Your Margin 56 Finding Margin Money 57 From Snowflake to Avalanche 58 Frequently Asked Questions About the Margin 67 Maximize Your Margin 68 Manage Your Spending to Maximize Your Margin 68 Impulse Buying - The Wealth Destroyer 69 Shrinking Santa’s Stocking 73 Happiness from the Depression 74 The C.I.A. -

1993 Buick Park Avenue Owner's Manual

i I 'Id?I ,\!la I1 I .. The 1993 Buick Park Avenue Owner's Manual Litho in U.S.A. @CopyrightGeneral Motors Corporation 1992 Part No. 25603705 B First Edition All Rights Reserved 1 We support voluntary technician certification. GENERAL MOTORS, GM and the GM Emblem, BUICK, and the BUICK Emblem are registered WE SUPPORT VOLUNTARY TECHNKIAN trademarks of General Motors Corporation. CERTIFICAT’WN THROUGH Nabonal lnstttute for AUTOMOTIVE SERVICE EXCELLENCE This manual includes the latest information at the time it was printed. We reserve the right to make changes in the product after that time without further notice. For vehicles For Canadian Owners Who Prefera first sold in Canada, substitute the name “General Motors of Canada Limited” for Buick Motor Division whenever it French Language Manual: appears in this manual. Aux propri6taires canadiens: Vous pouvez vous procurer un exemplaire de ce guide en fraqais chez votre Please keep this manual in your Buick, so it will be there if concessionaire ou B DGN Marketing Services Ltd., 1500 you ever need it when you’re on the road. If you sell the Bonhill Rd., Mississauga, Ontario L5T lC7. vehicle, please leave this manual in it so the new owner can use it. A 3 Walter Marr and Thomas Buick Buick’s chief engineer, Walter L. Man- (left), and Thomas D. Buick, son of founder David Dunbar Buick, drove the first FlintBuick in a successful Flint-Detroit round trip in July 1904. David Buick was building gasolineengines by 1899, and Marr, his .engineer, apparently built the first auto to be called a Buick in 1900. -

Bangor Students' China Study Abroad Cancelled Due to Coronavirus Fears

Sabb Election Gear up and learn what a Sabb is FREE Plan which Pages matches to 14-15 watch! Varsity Fixtures Page 62 February Issue 2020 Issue No. 282 seren.bangor.ac.uk @SerenBangor Y Bangor University Students’ Union English Language Newspaper Bangor students’ China study abroad cancelled due to Coronavirus fears “We were told that the second semester abroad in China was cancelled.” By ALEC TUDOR “As this was beginning of February tion as we don’t pay tuition fees during in China, the University has arranged MORE tudents undertaking a year abroad I was unsure about what was going to our year abroad, and thankfully the sta that they can remain in Bangor, stay- in China have been barred from happen for the rest of my year, I was are making the time for us to have a pro- ing in university accommodation, and entering the country due to the re- told that the lecturers and YA coordinat- ductive semester of Chinese.” they will receive specialist tuition which Scent COVID-19 epidemic. ing sta were discussing the latest time e University has released a state- will enable them to meet their learning INSIDE Following the UK Government’s deci- we could go and still have a pleasant ment concerning this situation: outcomes despite being unable to be in sion to advise against all travel to main- and bene cial time in China. A er two “Twelve of our students were due to China.” land China, Bangor University has told weeks of what I can assume was sta dis- visit China for the second semester as e funding is coming from the Stu- students not to go. -

THE WORDS of WOMEN SURVIVORS of NON-PHYSICAL ABUSE in INTIMATE PARTNER RELATIONSHIPS by JUDITH

THE EVIDENCE IS IN THE TELLING: THE WORDS OF WOMEN SURVIVORS OF NON-PHYSICAL ABUSE IN INTIMATE PARTNER RELATIONSHIPS by JUDITH CLARA POIRIER A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN NURSING in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA DECEMBER 2007 © Judith Clara Poirier, 2007 ABSTRACT Woman Abuse is recognized as a serious issue that is epidemic in Canadian society; women of any ethnicity, race, education, and socio-economic status are at risk. Although non-physical abuse is harmful, in the absence of physical abuse, it is often overlooked or minimized by potential helpers. Consequently, in the absence of physical abuse, understanding that the abuse is unacceptable and requires action, and having the abuse taken seriously by potential helpers, is more difficult. The purpose of this study was to better understand how women who have experienced non-physical abuse in an intimate partner relationship use language to describe, interpret, and evaluate their experiences, and how they communicate their understanding to others. In this qualitative study, the narrative method was used to examine how women use language to make meaning from their abuse experiences tempered by current personal, family, sociocultural, and environmental norms. Five women who self- identified as having experienced non-physical abuse in an intimate partner relationship participated in this study. Data analysis of in-depth interviews included an examination of the telling of the narrative, -

“Hunter of Doves” (PDF)

Hunter of Doves By Josephine Herbst First published in Botteghe Oscure, Quaderno XIII, 1954 The man had vanished. He was dead. Now he seemed in peril of a double death for the work that should have left his image clear was to be, it seemed, the exact medium that would forever blur him. His time, the elements in which he had had his chance, was already hopelessly muddled. The past had become the inglorious present and with it, her friend and his intention. Mrs. Heath, who had been the dead man’s friend in life, did not want any share in this betrayal. The danger was that no one intended to betray. There was nothing in the ingenuous face of the young man seated on the terrace of her house in the country to indicate that. His was a mute expression of rapt interest, of devotion to the dead man and his works. The expression even implied rites of purification and announced himself as the true Gabriel who would trumpet forth the connection between the dead man, Alec Barber, and the living works of the dead author, Noel Bartram. It was no secret that Barber had taken the name of Bartram. The cipher concealed a further enigma, not so well known, hiding the actual difficult name of his birth. So her friend had triply buried himself and behind his several masks had slipped on the final mask that dying bestowed. She tried to focus on the visitor. Surely, he was too youthful. He must have been a mere brat in the ’thirties when Noel Bartram was writing the three short novels that were the sum of his art.