Making the Edmund Rice Ethos a Reality: a Case Study in the Perceptions of Principals in Christian Brothers' Schools in Queensland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Authentic Expression of Edmund Rice Christian Brother Education

226 Catholic Education/December 2007 AUTHENTIC EXPRESSION OF EDMUND RICE CHRISTIAN BROTHER EDUCATION RAYMOND J. VERCRUYSSE, C.F.C. University of San Francisco The Congregation of Christian Brothers (CFC), a religious community which continues to sponsor and staff Catholic high schools, began in Ireland with the vision of Edmund Rice. This article surveys biographical information about the founder and details ongoing discussions within the community directed toward preserving and growing Rice’s vision in contemporary Catholic schools. BACKGROUND n 1802, Edmund Rice directed the laying of the foundation stone for IMount Sion Monastery and School. After several previous attempts of instructing poor boys in Waterford, this was to be the first permanent home for the Congregation of Christian Brothers. Rice’s dream of founding a reli- gious community of brothers was becoming a reality with a school that would reach out to the poor, especially Catholic boys of Waterford, Ireland. Edmund Rice grew up in Callan, County Kilkenny. The Rice family was described as “a quiet, calm, business people who derived a good living from the land and were esteemed and respected” (Normoyle, 1976, p. 2). Some historians place the family farm in the Sunhill townland section of the coun- ty. The family farm was known as Westcourt. It was at Westcourt that Robert Rice and Margaret Tierney began a life together. However, “this life on the family farm was to be lived under the partial relaxation of the Penal Laws of 1782” (Normoyle, 1976, p. 3). This fact would impact the way the Rice family would practice their faith and limit their participation in the local Church. -

What Type of Scholarships Are Available?

Our selected universities/colleges are: Bath: Bath Spa University (Study of Religions Department) Which subjects? Belfast: Queen’s University Belfast, St Mary’s University The aim of the Farmington Institute is to support and Head teachers can study any subjects which would be College and Stranmillis University College encourage Head teachers working in values and helpful to their schools. School Teacher Scholars are free Bristol: University of Bristol standards and teachers of Religious Education in to study any aspect of Religious Education they wish, but Cambridge: University of Cambridge, Faculty of schools. preference will be given to applicants whose work can be Education/Homerton College seen to be of direct value to the teaching of RE in schools. Durham: St Chad’s College, University of Durham The Institute awards Scholarships to UK based Head Occasionally, the Institute, in conjunction with one of its Exeter: University of Exeter (School of Education) teachers and Teachers of Religious Education and partner universities or colleges, may advertise for an RE Glasgow: University of Strathclyde (Faculty of Education) and associated subjects and publishes papers and reports, teacher to undertake research on a specific topic which is University of Glasgow relevant to RE. and arranges conferences. Lampeter/Carmarthen: University of Wales Trinity Saint David Lincoln: Bishop Grosseteste University and University of What type of Scholarships are available? Lincoln How much will it cost? Liverpool: Liverpool Hope University and Liverpool John The Scholarship will cover the cost of tuition, essential Scholarships are divided into two types: university- Moore University London: St Mary’s University, Twickenham local travel and, by negotiation with the school, the salary based and school/home based. -

Register of Heritage Places - Assessment Documentation

REGISTER OF HERITAGE PLACES - ASSESSMENT DOCUMENTATION HERITAGE COUNCIL OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA 11. ASSESSMENT OF CULTURAL HERITAGE SIGNIFICANCE The criteria adopted by the Heritage Council in November 1996 have been used to determine the cultural heritage significance of the place. PRINCIPAL AUSTRALIAN HISTORIC THEME(S) • 2.4 Migrating • 6.2 Establishing schools HERITAGE COUNCIL OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA THEME(S) • 402 Education and science 11. 1 AESTHETIC VALUE* Catholic Agricultural College, Bindoon has considerable aesthetic value due to the idiosyncratic forms of the buildings located there. The significant buildings exhibit a well resolved combination of architectural, symbolic and artistic motifs. (Criterion 1.1) Catholic Agricultural College, Bindoon has aesthetic significance for its architecture. The combination and use of both the 'Inter-War Free Classical' and 'Inter-War Romanesque' style characteristics throughout the place, culminating in the impressive main building and tower, exhibit design and artistic excellence. (Criterion 1.2) Catholic Agricultural College, Bindoon contributes to the aesthetic qualities of significant vistas to and from the place and the natural landscape within which it is located, particularly from the north side of its valley setting, and upon approach from the south. (Criterion 1.3) Catholic Agricultural College, Bindoon, with its substantial and idiosyncratic buildings, collectively forms an imposing cultural environment in a rural landscape. (Criteria 1.3 & 1.4) 11. 2 HISTORIC VALUE Catholic Agricultural College, Bindoon is associated with the child migration and child welfare policies implemented by the State and Federal Governments and the British Government in the first half of the twentieth century. (Criterion 2.2) * For consistency, all references to architectural style are taken from Apperly, Richard; Irving, Robert and Reynolds, Peter. -

Redox DAS Artist List for Period

Page: Redox D.A.S. Artist List for01.10.2020 period: - 31.10.2020 Date time: Title: Artist: min:sec 01.10.2020 00:01:07 A WALK IN THE PARK NICK STRAKER BAND 00:03:44 01.10.2020 00:04:58 GEORGY GIRL BOBBY VINTON 00:02:13 01.10.2020 00:07:11 BOOGIE WOOGIE DANCIN SHOES CLAUDIAMAXI BARRY 00:04:52 01.10.2020 00:12:03 GLEJ LJUBEZEN KINGSTON 00:03:45 01.10.2020 00:15:46 CUBA GIBSON BROTHERS 00:07:15 01.10.2020 00:22:59 BAD GIRLS RADIORAMA 00:04:18 01.10.2020 00:27:17 ČE NE BOŠ PROBU NIPKE 00:02:56 01.10.2020 00:30:14 TO LETO BO MOJE MAX FEAT JAN PLESTENJAK IN EVA BOTO00:03:56 01.10.2020 00:34:08 I WILL FOLLOW YOU BOYS NEXT DOOR 00:04:34 01.10.2020 00:38:37 FEELS CALVIN HARRIS FEAT PHARRELL WILLIAMS00:03:40 AND KATY PERRY AND BIG 01.10.2020 00:42:18 TATTOO BIG FOOT MAMA 00:05:21 01.10.2020 00:47:39 WHEN SANDRO SMILES JANETTE CRISCUOLI 00:03:16 01.10.2020 00:50:56 LITER CVIČKA MIRAN RUDAN 00:03:03 01.10.2020 00:54:00 CARELESS WHISPER WHAM FEAT GEORGE MICHAEL 00:04:53 01.10.2020 00:58:49 WATERMELON SUGAR HARRY STYLES 00:02:52 01.10.2020 01:01:41 ŠE IMAM TE RAD NUDE 00:03:56 01.10.2020 03:21:24 NO ORDINARY WORLD JOE COCKER 00:03:44 01.10.2020 03:25:07 VARAJ ME VARAJ SANJA GROHAR 00:02:44 01.10.2020 03:27:51 I LOVE YOU YOU LOVE ME ANTHONY QUINN 00:02:32 01.10.2020 03:30:22 KO LISTJE ODPADLO BO MIRAN RUDAN 00:03:02 01.10.2020 03:33:24 POROPOMPERO CRYSTAL GRASS 00:04:10 01.10.2020 03:37:31 MOJE ORGLICE JANKO ROPRET 00:03:22 01.10.2020 03:41:01 WARRIOR RADIORAMA 00:04:15 01.10.2020 03:45:16 LUNA POWER DANCERS 00:03:36 01.10.2020 03:48:52 HANDS UP / -

The Kirby Collection Catalogue Irish College Rome

Archival list The Kirby Collection Catalogue Irish College Rome ARCHIVES PONTIFICAL IRISH COLLEGE, ROME Code Date Description and Extent KIR / 1873/ 480 28 [Correspondence and personal notes by Sr. Maria Maddalena del Cuore di Gesù - see entry for KIR/1873/480] 480 29 [Correspondence and personal notes by Sr. Maria Maddalena del Cuore di Gesù - see entry for KIR/1873/480] 480 30 [Correspondence and personal notes by Sr. Maria Maddalena del Cuore di Gesù - see entry for KIR/1873/480] 480 31 [Correspondence and personal notes by Sr. Maria Maddalena del Cuore di Gesù - see entry for KIR/1873/480] 1 1 January Holograph letter from M. McAlroy, Tullamore, to Kirby: 1874 Soon returning to Australia. Sympathy for religious cruelly treated in Rome. Hopes there will be no further attempt to confiscate College property. 2pp 2 1 January Holograph letter from Sister Catherine, Convent of Mercy 1874 of Holy Cross, Killarney, to Kirby: Thanks Dr. Kirby for pictures. 4pp 3 1 January Holograph letter from Louisa Esmonde, Villa Anais, 1874 Cannes, Alpes Maritimes, France, to Kirby: Asks for prayers for dying child. 4pp 4 2 January Holograph letter from Sr. Maria Colomba Torresi, S. 1874 Giacomo alla Gongara, to Kirby: Spiritual matters. 2pp 5 2 January Holograph letter from +James McDevitt, Hotel de Russie, 1874 Naples, to Kirby: Greetings. Hopes Rev. Walker, of Raphoe, will soon be able to go on the missions. 2pp 6 3 January Holograph letter from Sr. Mary of the Cross, Edinburgh, to 1874 Kirby: Concerning approval of Rule. 6pp 1218 Archives Irish College Rome Code Date Description and Extent KIR / 1874/ 7 5 January Holograph letter from Denis Shine Lawlor, Hotel de la 1874 Ville, Florence, to Kirby: Sends cheque for Peter's Pence fund. -

Detention in Afghanistan and Guantánamo

Composite statement: Detention in Afghanistan and Guantanamo Bay Shafiq Rasul, Asif Iqbal and Rhuhel Ahmed 1. All three men come from Tipton in West Midlands, a poor area with a small community of Pakistani and Bangladeshi origin. The school all three attended is considered one of the worst in England. Rhuhel Ahmed and Asif Iqbal who are now both aged 22 were friends from school, although one year apart. Neither was brought up religiously but each was drawn towards Islam. Shafiq Rasul is now aged 27 and had a job working at the electronics store, Currys. He was also enrolled at the University of Central England. 2. This statement jointly made by them constitutes an attempt to set out details of their treatment at the hands of UK and US military personnel and civilian authorities during the time of their detention in Kandahar in Afghanistan in late December 2001 and throughout their time in American custody in Guantanamo Bay Cuba. This statement is a composite of the experiences of all 3. They are referred to throughout by their first names for brevity. There is far more that could be said by each, but that task is an open-ended one. They have tried to include the main features. 1 Detention in Afghanistan 3. All three men were detained in Northern Afghanistan on 28 November 2001 by forces loyal to General Dostum. They were loaded onto containers and transported to Sherbegan prison. The horrors of that transportation are well documented elsewhere and are not described in detail here. 4. According to information all three were given later, there were US forces present at the point they were packed into the containers together with almost 200 others. -

Pag1 Maurice F . for Services to UK-Dubai T

510325301413-06-00 14:36:46 EVEN Pag Table: NGSUPP PPSysB Unit: pag1 B24 THE LONDON GAZETTE MONDAY 19 JUNE 2000 SUPPLEMENT No. 1 Bridget Elizabeth, Mrs. W, Chairman, Maurice F. For services to UK-Dubai trade and Warwickshire Council for Voluntary Youth Services. community relations. For services to Young People. Professor George Ernest K, F.R.S. For services to John Richard W, Vice President, Wey and Arun particle physics research. Canal Trust. For services to Canal Restoration and Professor Paul K. For services to contemporary Conservation in West Sussex. history. Sydney Charles W. For services to the Professor Paul P. For services to UK-Spanish Blackheath Harriers and to Athletics. cultural relations. Steve W. For services to the Timble Housing John Nigel Barten S. For services to British Organisation Leeds, West Yorkshire. interests, California, USA. Patricia Lindsay, Mrs. W. For services to the O.B.E. community in Poyntington, Dorset. Sheila Elizabeth, Mrs. W, Member, of the To be Ordinary Officers of the Civil Division of the said Warrington Borough Council. For services to the Most Excellent Order: community in Cheshire. William Harvey A. For services to British Mary Elaine, Mrs. W , lately Customer Services commercial interests in Argentina. ffi O cer, H.M. Board of Inland Revenue. Richard Hargreaves A. For services to British Frederic Max W . For charitable services to the commercial interests in Mexico. ff community, especially Barnardo’s, in Su olk. Dr. Barbara Bertha B. For public service, Bermuda. Diane Doreen, Mrs. W , School Crossing Patrol, Andrew Mullion Barwick B. For services to the Warwickshire County Council. -

Agenda Volume 1

Agenda volume one The Conference 2020 Presbyteral and Representative Sessions By direction of the Conference, this Agenda has been sent by post to each member of the Representative Session. The President and Vice-President confidently appeal to all representatives to join, as far as they possibly can, in all the devotions of the Conference. Chaplains will be available throughout the Conference. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher Methodist Publishing © 2020 Trustees for Methodist Church Purposes British Library Cataloguing in Publication data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-85852-487-0 Published on behalf of the Methodist Church by METHODIST PUBLISHING Methodist Church House, 25 Marylebone Road, London NW1 5JR Printed by Vario Press Limited Langley Contents Conference Rules of Procedure 8 1. Election and Induction of the President and Vice-President 18 2. Methodist Council, part 1 22 3. Appointment of officers of the Conference 37 4. God For All-The Connexional Strategy for Evangelism and Growth 39 5. Conference Arrangements 83 6. Special Resolution 86 7. Connexional Allowances Committee 89 8. Report of the Trustees for the Bailiwick of Guernsey Methodist 100 Church Purposes 9. Trustees for Jersey Methodist Church Purposes 101 10. Methodist Forces Board 102 11. Methodist Homes (MHA) 105 12. 3Generate 2019 - Methodist Children and Youth Assembly 109 13. Unified Statement of Connexional Finances 116 14. -

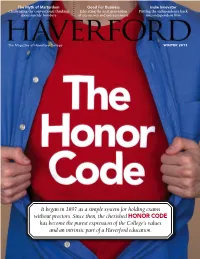

It Began in 1897 As a Simple System for Holding Exams Without Proctors

The Myth of Martyrdom Good For Business Indie Innovator Challenging the conventional thinking Educating the next generation Putting the independence back about suicide bombers of executives and entrepreneurs into independent film The Magazine of Haverford College WINTER 2013 It began in 1897 as a simple system for holding exams without proctors. Since then, the cherished HONOR CODE has become the purest expression of the College’s values and an intrinsic part of a Haverford education. 9 20 Editor Contributing Writers DEPARTMENTS Eils Lotozo Charles Curtis ’04 Prarthana Jayaram ’10 Associate Editor Lini S. Kadaba 2 View from Founders Rebecca Raber Michelle Martinez 4 Letters to the Editor Graphic Design Alison Rooney Tracey Diehl, Louisa Shepard 6 Main Lines Justin Warner ’93 Eye D Communications 15 Faculty Profile Assistant Vice President for Contributing Photographers College Communications Thom Carroll 20 Mixed Media Chris Mills ’82 Dan Z. Johnson Brad Larrison 25 Ford Games Vice President for Josh Morgan 48 Roads Taken and Not Taken Institutional Advancement Michael Paras Michael Kiefer Josh Rasmussen 49 Giving Back/Notes From Zachary Riggins the Alumni Association 54 Class News 65 Then and Now On the cover: Photo by Thom Carroll Back cover photo: Courtesy of Haverford College Archives The Best of Both Worlds! Haverford magazine is now available in a digital edition. It preserves the look and page-flipping readability of the print edition while letting you search names and keywords, share pages of the magazine via email or social networks, as well as print to your personal computer. CHECK IT OUT AT haverford.edu/news/magazine.php Haverford magazine is printed on recycled paper that contains 30% post-consumer waste fiber. -

Easter VI.Pmd

May is Mary’s Month! Our Lady of Grace. North transept, St. James Cathedral. ST. JAMES CATHEDRAL The Sixth Sunday of Easter May 25, 2014 May 25, 2014 Dear Friends, St. James Cathedral and O’Dea High School have a very strong relationship, one that goes back to the very beginning of the school. Did you know that the Cathedral actually built O’Dea? It’s true. Under the leadership of Monsignor James G. Stafford, Pastor of St. James Cathedral from 1919-1935, the Cathedral School experienced phenomenal growth. Not only did Monsignor Stafford offer free tuition and free books, he arranged for three daily busses so that children of outlying O'Dea Baseball Team, 1924 districts could enjoy the benefit of a Catholic education. By 1923 there were more than 600 students and the school was bursting at the seams. But this wasn’t enough for Monsignor Stafford or for the Cathedral parishioners. Recognizing the great need for a Catholic boys’ high school in the area, he purchased property on the block east of the Cathedral. Eight houses were torn down to make way for the high school, while two houses became residences for the Holy Names Sisters, who taught at the Cathedral School, and the Irish Christian Brothers, who were invited to undertake the management of the new O’Dea High School. The parish undertook these projects with extraordinary vision and generosity. As the Cathedral’s 1929 Yearbook reported: “With the determination that this great parish should offer our young men an institution of learning equal to anything in the country, he planned a structure of outstanding beauty and usefulness. -

The Lasallian Catechetical Heritage in the United States Today.” AXIS: Journal of Lasallian Higher Education 4, No

Rummery, Gerard. “The Lasallian Catechetical Heritage in the United States Today.” AXIS: Journal of Lasallian Higher Education 4, no. 3 (Institute for Lasallian Studies at Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota: 2013). © Gerard Rummery, FSC, Ph.D. Readers of this article have the copyright owner’s permission to reproduce it for educational, not-for-profit purposes, if the author and publisher are acknowledged in the copy. The Lasallian Catechetical Heritage in the United States Today Gerard Rummery, FSC, Ph.D., Lasallian Education Services, Malvern, VIC, Australia1 Part One: The Achievement The Inculturation of the Lasallian Charism The particular situation of Lasallian schools in the United States today is different in so many ways from that faced by John Baptist de La Salle and the first Brothers over 300 years ago, and indeed from that confronted by the pioneer Brothers in the melting-pot days of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Today, most Lasallians work mainly in high schools and in tertiary education, although some in the Saint Miguel schools now find themselves working in grade schools with immigrant children, just as the pioneers did. The legacy of what De La Salle initiated with delinquent young people at Saint-Yon continues in works such as the Saint Gabriel System, at Ocean Tides, Martin de Porres School and Group Homes. Direct service of the poor is a concern of each District in its links with the Catholic Worker movement and in the many works with immigrant people. Our first observation, therefore, is to note that the Brothers who came to work in an English- speaking immigrant country had first to adjust their training and cultural background to a very different situation in which their Institute’s well-established and successful French practices and pedagogy had to undergo major changes. -

Advent 2008 Update (Pdf)

Advent 2008 From the Postulator's Desk: ‘O Come, O Come, Emmanuel!’ It’s Advent, that time of year when we look forward to a better future, to a fuller realisation of our hopes and dreams both for ourselves and for our loved ones at Christmas and in the New Year in the company of the Christ Child and Blessed Edmund. In a time of recession, let us hope that our priorities are mature and generous – and inclusive. Sincere thanks for all the prayers and good wishes during and after my recent visit to hospital. It is only now that I feel sufficiently recovered to offer an explanation to the many clients of Blessed Edmund for being unavailable in my office in the recent past. It is great to be alive! 1. Health Scare Yes, indeed, 2008 has been an ‘annus horribilis’ for me, health-wise. After relocating the Postulator’s Office from Rome to Dublin, I experienced extreme tiredness and I was advised to have a full medical check-up. It was discovered that I was suffering from hypertension and pernicious anaemia. I was put on a course of medication, including monthly injections of Vitamin B12. During Summer 2008, I began to experience bouts of severe headaches but, seeing that I had been subject to migraine headaches in the past, I concluded that this was more of the same, due to the trauma of relocating from Rome and settling down in Dublin after four consecutive years in the Eternal City (I had spent another six years there in the 1980s).