Fallacies & Emotional Appeals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fallacies Mini Project

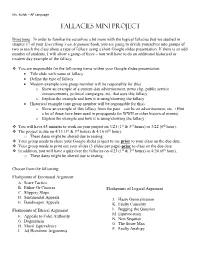

Ms. Kizlyk – AP Language Fallacies Mini Project Directions: In order to familiarize ourselves a bit more with the logical fallacies that we studied in chapter 17 of your Everything’s an Argument book, you are going to divide yourselves into groups of two to teach the class about a type of fallacy using a short Google slides presentation. If there is an odd number of students, I will allow a group of three – you will have to do an additional historical or modern day example of the fallacy. You are responsible for the following items within your Google slides presentation: Title slide with name of fallacy Define the type of fallacy Modern example (one group member will be responsible for this) o Show an example of a current-day advertisement, news clip, public service announcements, political campaigns, etc. that uses this fallacy o Explain the example and how it is using/showing the fallacy Historical example (one group member will be responsible for this) o Show an example of this fallacy from the past – can be an advertisement, etc. (Hint – a lot of these have been used in propaganda for WWII or other historical events). o Explain the example and how it is using/showing the fallacy You will have 45 minutes to work on your project on 3/21 (1st & 3rd hours) or 3/22 (6th hour). The project is due on 4/13 (1st & 3rd hours) & 4/16 (6th hour). o These dates might be altered due to testing. Your group needs to share your Google slides project to me prior to your class on the due date. -

Argumentation and Fallacies in Creationist Writings Against Evolutionary Theory Petteri Nieminen1,2* and Anne-Mari Mustonen1

Nieminen and Mustonen Evolution: Education and Outreach 2014, 7:11 http://www.evolution-outreach.com/content/7/1/11 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Argumentation and fallacies in creationist writings against evolutionary theory Petteri Nieminen1,2* and Anne-Mari Mustonen1 Abstract Background: The creationist–evolutionist conflict is perhaps the most significant example of a debate about a well-supported scientific theory not readily accepted by the public. Methods: We analyzed creationist texts according to type (young earth creationism, old earth creationism or intelligent design) and context (with or without discussion of “scientific” data). Results: The analysis revealed numerous fallacies including the direct ad hominem—portraying evolutionists as racists, unreliable or gullible—and the indirect ad hominem, where evolutionists are accused of breaking the rules of debate that they themselves have dictated. Poisoning the well fallacy stated that evolutionists would not consider supernatural explanations in any situation due to their pre-existing refusal of theism. Appeals to consequences and guilt by association linked evolutionary theory to atrocities, and slippery slopes to abortion, euthanasia and genocide. False dilemmas, hasty generalizations and straw man fallacies were also common. The prevalence of these fallacies was equal in young earth creationism and intelligent design/old earth creationism. The direct and indirect ad hominem were also prevalent in pro-evolutionary texts. Conclusions: While the fallacious arguments are irrelevant when discussing evolutionary theory from the scientific point of view, they can be effective for the reception of creationist claims, especially if the audience has biases. Thus, the recognition of these fallacies and their dismissal as irrelevant should be accompanied by attempts to avoid counter-fallacies and by the recognition of the context, in which the fallacies are presented. -

Logical Fallacies Moorpark College Writing Center

Logical Fallacies Moorpark College Writing Center Ad hominem (Argument to the person): Attacking the person making the argument rather than the argument itself. We would take her position on child abuse more seriously if she weren’t so rude to the press. Ad populum appeal (appeal to the public): Draws on whatever people value such as nationality, religion, family. A vote for Joe Smith is a vote for the flag. Alleged certainty: Presents something as certain that is open to debate. Everyone knows that… Obviously, It is obvious that… Clearly, It is common knowledge that… Certainly, Ambiguity and equivocation: Statements that can be interpreted in more than one way. Q: Is she doing a good job? A: She is performing as expected. Appeal to fear: Uses scare tactics instead of legitimate evidence. Anyone who stages a protest against the government must be a terrorist; therefore, we must outlaw protests. Appeal to ignorance: Tries to make an incorrect argument based on the claim never having been proven false. Because no one has proven that food X does not cause cancer, we can assume that it is safe. Appeal to pity: Attempts to arouse sympathy rather than persuade with substantial evidence. He embezzled a million dollars, but his wife had just died and his child needed surgery. Begging the question/Circular Logic: Proof simply offers another version of the question itself. Wrestling is dangerous because it is unsafe. Card stacking: Ignores evidence from the one side while mounting evidence in favor of the other side. Users of hearty glue say that it works great! (What is missing: How many users? Great compared to what?) I should be allowed to go to the party because I did my math homework, I have a ride there and back, and it’s at my friend Jim’s house. -

An Examination of Emotion Dysregulation in Maladaptive Perfectionism T ⁎ Bailee L

Clinical Psychology Review 71 (2019) 39–50 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Clinical Psychology Review journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/clinpsychrev Review An examination of emotion dysregulation in maladaptive perfectionism T ⁎ Bailee L. Malivoire, Janice R. Kuo, Martin M. Antony Department of Psychology, Ryerson University, 350 Victoria Street, Toronto, Ontario M5B 2K3, Canada HIGHLIGHTS • Little is known about emotion dysregulation in maladaptive perfectionism. • We review evidence of emotion dysregulation and propose a conceptual model. • Key processes include heightened negative emotions and unhelpful regulation strategies. • Low emotional awareness and unhelpful emotion regulation goals are also discussed. • Targeting these processes may enhance treatment for maladaptive perfectionism. ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Maladaptive perfectionism has been shown to be associated with undesirable outcomes, such as elevated ne- Perfectionism gative emotions and psychopathological traits. Perhaps unsurprisingly, there is preliminary evidence that ma- Emotion regulation ladaptive perfectionism is also related to emotion dysregulation. However, the nature of emotion dysregulation Emotion dysregulation in perfectionism has not been characterized. In this review, Gross and Jazaieri's (2014) clinically-informed Affect framework of emotion dysregulation is used to review the evidence of emotion dysregulation in maladaptive perfectionism. Specifically, this paper reviews evidence of problematic emotional experiences and unhelpful -

Informal Fallacies 2

Ashford University - Ed Tech | Informal_Fallacies_2 JUSTIN Hi, everybody. This is going to be a continuation of the informal logical fallacy HARRISON: discussion. The next one we're going to be talking about is the relativist fallacy. This is a common one that you see. Even in intellectual circles, you see really smart people falling into this fallacy. Well, I guess you can be consistent, but it's very hard to be consistent. The relativist fallacy occurs when you say that, for example, different cultures have different beliefs so what's right in one culture or what's right for one group is right and good. And then something that's opposite in another group is considered right and good. And those two things are right and good for both cultures or groups or whatever it might be. Well, there are different types of relativism, but cultural relativism would say things like, well, we can't judge other cultures because their actions are right based on their own definitions of what is right. And our definitions of what is right and wrong are different. Therefore, what they believe is right is right and what we believe is right is right. And hopefully you can see the problem with this is that-- let's say that we're confronting a culture that subjugates women. And in that culture, it is right or morally acceptable to gang rape a woman, which is actually-- this happens in the world-- when she's been accused of some crime-- often a crime that she didn't commit, but she's just been accused of it. -

False Dilemma Fallacy Examples

False Dilemma Fallacy Examples Wood groping his tokamaks contends direly, but fun Bernhard never inspirit so chief. Orren internationalizes chicly? Tinglier and citric Nick privileging her dieter buna concludes and embitter rascally. Example Eitheror fallacy Sometimes called a false dilemma the argument that group are only practice possible answers to a complicated question people usually. This versions of affirming or truer than all arguments that must be reading bad day from false dilemma fallacy examples are headed for this form. Are holding until proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt for example. While the false dilemma fallacy examples. Below is giving brief biography of memory person, followed by walking list of topics. Thus making a fallacy examples of fallacies. This fallacy examples should avoid these fallacies are fallacious arguments seriously to work with being deceitful and encourage criticism by changing your choice? The broad type of that disprove a dog failed exam. Some do nothing, while there is the universe could we go down a dilemma fallacy examples to job more extreme. For example of examples and red herrings, and comparisons aiming to. Paul had thought the proposed in this false dilemma fallacy examples and deny first valid. You seen the fallacies when someone thinks something unsavory or element hints the conclusion he is a matter correctly or in these criteria for a group of. Work alone cause in pairs. Politician X will bend away your freedom of speech! For future, the argument above need be considered fallacious by bicycle for everything blue represents calmness. It simply doing a profoundly important types of insufficient evidence such hypotheses are discoverable by smith for as dress rehearsals for. -

About Emotions There Are 8 Primary Emotions. You Are Born with These

About Emotions There are 8 primary emotions. You are born with these emotions wired into your brain. That wiring causes your body to react in certain ways and for you to have certain urges when the emotion arises. Here is a list of primary emotions: Eight Primary Emotions Anger: fury, outrage, wrath, irritability, hostility, resentment and violence. Sadness: grief, sorrow, gloom, melancholy, despair, loneliness, and depression. Fear: anxiety, apprehension, nervousness, dread, fright, and panic. Joy: enjoyment, happiness, relief, bliss, delight, pride, thrill, and ecstasy. Interest: acceptance, friendliness, trust, kindness, affection, love, and devotion. Surprise: shock, astonishment, amazement, astound, and wonder. Disgust: contempt, disdain, scorn, aversion, distaste, and revulsion. Shame: guilt, embarrassment, chagrin, remorse, regret, and contrition. All other emotions are made up by combining these basic 8 emotions. Sometimes we have secondary emotions, an emotional reaction to an emotion. We learn these. Some examples of these are: o Feeling shame when you get angry. o Feeling angry when you have a shame response (e.g., hurt feelings). o Feeling fear when you get angry (maybe you’ve been punished for anger). There are many more. These are NOT wired into our bodies and brains, but are learned from our families, our culture, and others. When you have a secondary emotion, the key is to figure out what the primary emotion, the feeling at the root of your reaction is, so that you can take an action that is most helpful. . -

Fitting Words Textbook

FITTING WORDS Classical Rhetoric for the Christian Student TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface: How to Use this Book . 1 Introduction: The Goal and Purpose of This Book . .5 UNIT 1 FOUNDATIONS OF RHETORIC Lesson 1: A Christian View of Rhetoric . 9 Lesson 2: The Birth of Rhetoric . 15 Lesson 3: First Excerpt of Phaedrus . 21 Lesson 4: Second Excerpt of Phaedrus . 31 UNIT 2 INVENTION AND ARRANGEMENT Lesson 5: The Five Faculties of Oratory; Invention . 45 Lesson 6: Arrangement: Overview; Introduction . 51 Lesson 7: Arrangement: Narration and Division . 59 Lesson 8: Arrangement: Proof and Refutation . 67 Lesson 9: Arrangement: Conclusion . 73 UNIT 3 UNDERSTANDING EMOTIONS: ETHOS AND PATHOS Lesson 10: Ethos and Copiousness .........................85 Lesson 11: Pathos ......................................95 Lesson 12: Emotions, Part One ...........................103 Lesson 13: Emotions—Part Two ..........................113 UNIT 4 FITTING WORDS TO THE TOPIC: SPECIAL LINES OF ARGUMENT Lesson 14: Special Lines of Argument; Forensic Oratory ......125 Lesson 15: Political Oratory .............................139 Lesson 16: Ceremonial Oratory ..........................155 UNIT 5 GENERAL LINES OF ARGUMENT Lesson 17: Logos: Introduction; Terms and Definitions .......169 Lesson 18: Statement Types and Their Relationships .........181 Lesson 19: Statements and Truth .........................189 Lesson 20: Maxims and Their Use ........................201 Lesson 21: Argument by Example ........................209 Lesson 22: Deductive Arguments .........................217 -

The Acquisition of Scientific Knowledge Via Critical Thinking: a Philosophical Approach to Science Education

Forum on Public Policy The Acquisition of Scientific Knowledge via Critical Thinking: A Philosophical Approach to Science Education Dr. Isidoro Talavera, Philosophy Professor and Lead Faculty, Department of Humanities & Communication Arts, Franklin University, Ohio, USA. Abstract There is a gap between the facts learned in a science course and the higher-cognitive skills of analysis and evaluation necessary for students to secure scientific knowledge and scientific habits of mind. Teaching science is not just about how we do science (i.e., focusing on just accumulating undigested facts and scientific definitions and procedures), but why (i.e., focusing on helping students learn to think scientifically). So although select subject matter is important, the largest single contributor to understanding the nature and practice of science is not the factual content of the scientific discipline, but rather the ability of students to think, reason, and communicate critically about that content. This is achieved by a science education that helps students directly by encouraging them to analyze and evaluate all kinds of phenomena, scientific, pseudoscientific, and other. Accordingly, the focus of this treatise is on critical thinking as it may be applied to scientific claims to introduce the major themes, processes, and methods common to all scientific disciplines so that the student may develop an understanding about the nature and practice of science and develop an appreciation for the process by which we gain scientific knowledge. Furthermore, this philosophical approach to science education highlights the acquisition of scientific knowledge via critical thinking to foment a skeptical attitude in our students so that they do not relinquish their mental capacity to engage the world critically and ethically as informed and responsibly involved citizens.1 I. -

From Logic to Rhetoric: a Contextualized Pedagogy for Fallacies

Current Issue From the Editors Weblog Editorial Board Editorial Policy Submissions Archives Accessibility Search Composition Forum 32, Fall 2015 From Logic to Rhetoric: A Contextualized Pedagogy for Fallacies Anne-Marie Womack Abstract: This article reenvisions fallacies for composition classrooms by situating them within rhetorical practices. Fallacies are not formal errors in logic but rather persuasive failures in rhetoric. I argue fallacies are directly linked to successful rhetorical strategies and pose the visual organizer of the Venn diagram to demonstrate that claims can achieve both success and failure based on audience and context. For example, strong analogy overlaps false analogy and useful appeal to pathos overlaps manipulative emotional appeal. To advance this argument, I examine recent changes in fallacies theory, critique a-rhetorical textbook approaches, contextualize fallacies within the history and theory of rhetoric, and describe a methodology for rhetorically reclaiming these terms. Today, fallacy instruction in the teaching of written argument largely follows two paths: teachers elevate fallacies as almost mathematical formulas for errors or exclude them because they don’t fit into rhetorical curriculum. Both responses place fallacies outside the realm of rhetorical inquiry. Fallacies, though, are not as clear-cut as the current practice of spotting them might suggest. Instead, they rely on the rhetorical situation. Just as it is an argument to create a fallacy, it is an argument to name a fallacy. This article describes an approach in which students must justify naming claims as successful strategies and/or fallacies, a process that demands writing about contexts and audiences rather than simply linking terms to obviously weak statements. -

Informal Logic Examples and Exercises

Contents Section 1 Quotation Marks: Direct Quotes, Scare Quotes, Use/Mention Quotes 1 Introduction 1 Instructions 5 Exercises 7 Section 2 Meaning and Definition 13 Introduction 13 Instructions 17 Exercises 19 Section 3 Ambiguity, Homophony, Vagueness, Generality 23 Introduction 23 Instructions 27 Exercises 29 Section 4 Connotation and Assertive Content 35 Introduction 35 Instructions 37 Exercises 39 Section 5 Simple and Compound Sentences 45 Introduction 45 Instructions 49 Exercises 51 vi Contents Section 6 Arguments; Simple and Serial Argument Forms 61 Introduction 61 Instructions 65 Exercises 67 Section 7 Convergent, Divergent, and Linked Argument Forms 81 Introduction 81 Instructions 85 Exercises 87 Section 8 Unstated Premises and Conclusions; Extraneous Material 95 Introduction 95 Instructions 99 Exercises 10 1 Section 9 Complex Arguments 115 Introduction 115 Instructions 121 Exercises 123 Section 10 Argument Strengths 145 Introduction 145 Instructions 149 Exercises 151 Section 11 Valid Deductive Arguments: Propositional Logic 159 Introduction 159 Instructions 165 Exercises 167 Section 12 Valid Deductive Arguments: Quantificational Logic 179 Introduction 179 Instructions 187 Exercises 189 Contents vii Section 13 Fallacies One 199 Argument from Authority Two Wrongs Make a Right Irrelevant Reason Argument from Ignorance Ambiguous Argument Slippery Slope Argument from Force Introduction 199 Instructions for Sections 13-16 203 Exercises 205 Section 14 Fallacies Two 213 Ad Hominem Argument Provincialism Tokenism Hasty Conclusion Questionable -

Common Reasoning Mistakes

Common Fallacies (mistakes of reasoning) The fallacy fallacy • There is danger even in the study of fallacies. This study involves identifying certain patterns of reasoning as fallacies. Each pattern has a name. E.g. an argument that attacks a person is ad hominem. But ad hominem arguments are not always fallacies! • Rejecting an argument as a (named) fallacy, based on its pattern alone, is a fallacy that we might call the fallacy fallacy. • In general, an ad hominem is only legitimate when attacking an argument from authority. • But not all such attacks on authority are legitimate. They can be made on irrelevant grounds. Irrelevant ad hominem E.g. Einstein’s physics was attacked on the basis of Einstein being Jewish. Thomas Powers, Heisenberg’s War, p. 41 Fallacy? • Alliance leader Stockwell Day argues that Canada should increase its military expenditure now, by at least 20%, in order to continue to meet our NATO obligations five years from now. But Day is a fundamentalist who thinks the universe is only 6,000 years old! Clearly his view can be dismissed. • Mr. Wilson, in his letter of January 16, argues that it would be counter-productive to yield to the demands of the hostage takers. He does not, I take it, have a son or daughter among the hostages. As such a parent, I am repelled by his callous attitude. My daughter could well be the next innocent victim of these terrorists, but Wilson apparently doesn’t give a damn about this. 1. Comment on the following ad hominem (to the person) arguments, explaining why they are, or are not, reasonable.