Above the Falls – a Master Plan for the Upper River in Minneapolis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

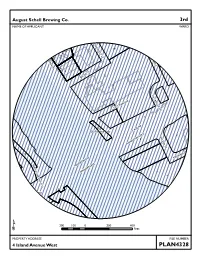

4 Island Ave W Documentation

August Schell Brewing Co. 3rd NAME OF APPLICANT WARD 71 NICOLLET ST 207 201 49 45 ISLAND AVE E 220 ISLAND AVE W 41 31 33 35 37 39 43 51 53 108 6 4 14 12 GROVE ST 25 DE LASALLE DR EASTMAN AVE St. Anthony Falls 1ST AVE NE WILDER ST 95 HENNEPIN AVE E 2 105 9 MERRIAM ST WEST RIVER PKWY N HENNEPIN AVE 90 HENNEPIN AVE 20 16 22 5 Minneapolis Warehouse 1 100 3 200 100 0 200 400 ¹ Feet PROPERTY ADDRESS FILE NUMBER 4 Island Avenue West PLAN4328 NPS Form 1 0-900-a (Rev. 812002) OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior _Grain Belt Beer Sign National Park Service Name of Property Hennepin County, Minnesota National Register of Historic Places County and State N/A Continuation Sheet Name of multiple listing (if applicable) Section number Additional Documentation Page 2 Figure 2: A Grain Belt Beer Sign on the roof of the Marigold Ballroom, 1330-1342 Nicollet A venue, March 4, 1950. Source: Norton and Peel Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, Saint Paul, Minnesota. NPS Form 10-900-a (Rev. 8/2002) OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior Grain Belt Beer_c:::._ Sign ____ _ National Park Service Name of Property _Hennepin County, Minnesota National Register of Historic Places County and State N/A Continuation Sheet Name of multiple listing (if applicable) Section number Additional Documentation Page 5 Figure 5: The Grain Belt Beer Sign on Nicollet Island, viewed from Hennepin A venue near First Street, July 31, 1951. -

Above the Falls Master Plan Update

ABOVE THE FALLS MASTER PLAN UPDATE CITY OF MINNEAPOLIS CPED – LONG RANGE PLANNING DIVISION 105 5TH AVENUE SOUTH, SUITE 200 MINNEAPOLIS, MN 55401 ADOPTED BY CITY COUNCIL JUNE 14, 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY Above the Falls Vision 8 Guiding Principles 8 Plan Overview 9 Implementation Strategy 10 Summary of Recommendations 10 CHAPTER 2. CONTEXT History and Background 14 Planning Process 18 Coordination and Outreach 20 Existing Conditions Summary 22 Constraints and Opportunities 42 CHAPTER 3. POLICY ISSUES Commercial Navigation 48 Community and Economic Development 51 Implementation Model 53 CHAPTER 4. SUPPORTING ANALYSES Health Impact Analysis 56 Market Analysis 59 Economic and Fiscal Analysis 63 Land Use and Availability Analysis 68 CHAPTER 5. LAND USE AND URBAN DESIGN PLAN Land Use Principles 72 Design Guidelines 77 Recommendations by Subarea 79 Recommendations 108 CHAPTER 6. PARKS AND TRAILS PLAN Planning Framework 116 Park Description and Boundary 117 Park Vision 118 Park Development Concept 118 Park Projects 121 Parkway Development and Phasing Strategy 124 Recommendations 124 CHAPTER 7. ENVIRONMENT AND INFRASTRUCTURE PLAN Environmental Restoration 128 Stormwater 134 Transportation Networks 140 Recommendations 159 CHAPTER 8. COMMUNITY AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT PLAN Principles and Goals 164 Community Development and Housing 164 Employment Growth and Linkages 167 Recommendations 170 CHAPTER 9. IMPLEMENTATION PLAN Benefits of Implementation 174 Progress Since Original Plan 174 New Implementation Structure 176 Priority Plan 176 Land Use and Urban Design 180 Parks and Trails 186 Environment and Infrastructure 187 Community and Economic Development 189 Vision Plan 191 Organizational Framework 193 Strategies and Tools 197 Resources 200 Approval Process 201 APPENDICES A. -

The Minnesota Innovation Park

The Minnesota Innovation Park Developer: The Wall Companies Architect: RSP Architects The Wall Companies is a privately-held collection of real estate related Established in 1978, RSP Architects is currently #15 on the Building development, acquisition and management companies. The principals Design & Construction list of architectural giants. Working holistically, have a combined 50 plus years of real estate experience, mostly in RSP Architects proactively manages our clients’ real estate needs the Twin Cities area. The Wall Companies has substantial expertise and excels at finding efficiencies through design to create inviting, in designing, constructing, and financing successful real estate sustainable, productive environments. They serve a diverse range development projects. Over the years, the company has developed, of clients nationally and internationally, including many Fortune owned and/or renovated over 1,200 residential units, and over 2 500 companies. They provide architectural design services; tenant million square feet of retail, office, and industrial property. The Wall improvement and workspace strategies; master planning; interior Companies was involved in the development of Metro Office Park and design; gaming layouts; facility management analytics; asset Normandale Office Park in Bloomington. The Wall Companies has management; facility planning; and experience design. RSP’s clients considerable experience building teams of diverse private and public are category leaders in hospitality, corporate, government, retail, partners to complete its development projects. healthcare, education, institutional, tribal gaming and science and technology industries. In addition to real estate projects, The Wall Companies owns the St. Paul-based Highland Bank with five Twin Cities locations and over RSP Architects is headquartered in the historic former Grain Belt Brew $450 million in assets. -

Above the Falls Regional Park Master Plan

SECTION 2 Park Background ABOVE THE FALLS REGIONAL PARK MASTER PLAN PARK MASTER PLAN Minneapolis Park & Recreation Board PAGE 2-1 LOCATION, HISTORY, AND CONTEXT The 105-acre Above the Falls Regional Park is located along both banks of the upper Mississippi River in Minneapolis. The park extends from Plymouth Avenue North/8th Avenue NE on the south to the Camden Bridge (N 43rd Avenue/37th Avenue NE) on the north. The park encompasses a 2.75 mile stretch of the Mississippi River. As shown in Figure 2.1, Above the Falls Regional Park is one of a series of regional parks along the Mississippi River in Minneapolis. To the north of ATF Regional Park is North Mississippi Regional Park, which extends to the City’s northern boundary at N 53rd Avenue. To the south, the Central Mississippi Riverfront Regional Park extends from N Plymouth Avenue/8th Avenue NE to Interstate 35W on both sides of the river. Farther down river are Mississippi Gorge Regional Park, Minnehaha Regional Park, and Fort Snelling State Park. Land use in the upper River corridor has fluctuated for the last 125 years in response to market trends, technology and available resources. Until the late 1990s, the vision for this part of the Mississippi was for a working river that would support an industrial economy. The area was first developed with saw mills, lumberyards, and foundries due to its location just above St. Anthony Falls. As rail transportation increased, railroad yards were located on both banks and a railroad bridge was constructed across the river. -

Little Falls' Historic Contexts

Little Falls‘ Historic Contexts Final Report of an Historic Preservation Planning Project Submitted to the Little Falls Heritage Preservation Commission And the City of Little Falls July 1994 Prepared by: Susan Granger and Scott Kelly Gemini Research Morris, MN 56267 Little Falls’ Historic Contexts Final Report of an Historic Preservation Planning Project Submitted to the Little Falls Heritage Preservation Commission And the city of Little Falls July 1994 Prepared by Susan Granger and Scott Kelly Gemini Research, Morris Minnesota This project has been financed in part with Federal funds from the National Park Service, Department of the Interior, through the Minnesota Historical Society under the provisions of the National Historic Preservation Act as amended. However, the contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendations by the Department of the Interior. This program receives Federal funds from the National Park Service. Regulations of the U.S. Department of the Interior strictly prohibit unlawful discrimination in departmental federally assisted Programs based on race, color, national origin, age, or handicap. Any person who believes he or she has been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility operated by a recipient of Federal assistance should write to: Director, Equal Opportunity Program, U. S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, PO Box 37127, Washington, D.C. 20013-7127. Table of Contents I. Introduction…………………………………………………………………..01 II. Historic Contexts……………………………………………………………05 III. Native Americans and Euro-American Contact…………....…...05 Transportation………………………………………………….………17 Logging…………………………………………………………………...29 Agriculture and Industry……………………………………….…...39 Commerce………………………………………………….….………….53 Public and Civic Life…………………………………..……………….61 Cultural Development………………………………………………...73 Residential Development…………………………..…….………….87 IV. -

![[Nps-Waso-Nrnhl-21417] [Ppwocradi0](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1984/nps-waso-nrnhl-21417-ppwocradi0-5241984.webp)

[Nps-Waso-Nrnhl-21417] [Ppwocradi0

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 07/15/2016 and available online at http://federalregister.gov/a/2016-16712, and on FDsys.gov 4312-51 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR National Park Service [NPS-WASO-NRNHL-21417] [PPWOCRADI0, PCU00RP14.R50000] National Register of Historic Places; Notification of Pending Nominations and Related Actions AGENCY: National Park Service, Interior. ACTION: Notice. SUMMARY: The National Park Service is soliciting comments on the significance of properties nominated before June 25, 2016, for listing or related actions in the National Register of Historic Places. DATES: Comments should be submitted by [INSERT DATE 15 DAYS AFTER DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER]. ADDRESSES: Comments may be sent via U.S. Postal Service to the National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service, 1849 C St. NW, MS 2280, Washington, DC 20240; by all other carriers, National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service, 1201 Eye St. NW, 8th floor, Washington, DC 20005; or by fax, 202-371-6447. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: The properties listed in this notice are being considered for listing or related actions in the National Register of Historic Places. Nominations for their consideration were received by the National Park Service before June 25, 2016. Pursuant to section 60.13 of 36 CFR part 60, 1 written comments are being accepted concerning the significance of the nominated properties under the National Register criteria for evaluation. Before including your address, phone number, e-mail address, or other personal identifying information in your comment, you should be aware that your entire comment – including your personal identifying information – may be made publicly available at any time. -

Tales of Bottineau

Tales of Bottineau Conducted on behalf of Bottineau Neighborhood Association Prepared by James Hamilton, Undergraduate Research Assistant Macalester College August 2002 Bottineau Neighborhood “Tales of Bottineau” A history project sponsored by the Bottineau Neighborhood Association and the Center for Urban and Regional Affairs August 2002 Neighborhood Planning for Community Revitalization (NPCR) supported the work of the author of this report but has not reviewed it for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and is not necessarily endorsed by NPCR. NPCR is coordinated by the Center for Urban and Regional Affairs at the University of Minnesota. NPCR is supported by grants from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s East Side Community Outreach Partnership Center, the McKnight Foundation, Twin Cities Local Initiatives Support Cooperation (LISC), the St. Paul Foundation, and The St. Paul. Neighborhood Planning for Community Revitalization 330 Hubert H. Humphrey Center 301 - 19th Avenue South Minneapolis, MN 55455 phone: 612/625-1020 e-mail: [email protected] website: http:www.npcr.org Table of Contents 1 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................................................................3 INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................................................................................................................4 IMMIGRATION -

Minnesota Statewide Historic Railroads Study Final MPDF

NPS Form 10-900-a OMB No. 1024-0018 (8-86) Expires 12-31-2005 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet Section: E Page 5 Railroads in Minnesota, 1862-1956 Name of Property Minnesota, Statewide County and State Section E. Statement of Historic Contexts I. Railroad Development in Minnesota, 1862-1956 Setting the Stage: Early Railroads Due to the country’s vast geographic expanse, transportation has always been a significant issue in America, influencing production, trade, travel, and communication in ways unknown to more compact European nations. In particular, as Euro-American settlers streamed into the trans-Appalachian west during the early nineteenth century, the United States needed an overland transportation system to link different regions of the country. From early roads to canals and finally to railroads, Americans built a transportation system by the turn of the twentieth century that was larger and more complex than any other in the world. The transformation of transportation in America began with the era of canal building. Although a system of roads extending westward from the major seaports had been established by 1820, water-borne transportation was more efficient for shipping heavy freight and generally faster than overland transport. Completion of the Erie Canal in 1825 demonstrated that canals could be built over long distances to connect major waterways and could be operated profitably. The immediate success of the Erie Canal led to a canal building boom that lasted through the 1830s. The network of canals and natural waterways provided antebellum America with important interregional links to exchange raw materials and manufactured goods, to transport passengers, and to deliver mail. -

LIVING with the MISSISSIPPI by Rachel Hines

LIVING WITH THE MISSISSIPPI By Rachel Hines “Living with the Mississippi” is a blog series that examines the history of the river flats communities and what it means to almost literally live on the Mississippi River. Follow along to learn more about life on the Mississippi prior to luxury con- dos and clean river water, before the riverfront was considered a desirable place to live. First published online for River Life at http://riverlife.umn.edu/rivertalk in December, 2014 with comments by Pat Nunnally, River Life. LIVING WITH THE MISSISSIPPI WORKING ON THE RIVER by Rachel Hines For many residents of the river flats communities, the brewery quickly changed hands and became the Noeren- river was not only a place to live, but also a place to work. berg Brewery in 1880, while Kraenzlein and Miller became Employment originally drew settlers to the Bohemian Flats. Heinrich and Mueller in 1884. These two breweries joined After the Kraenzlein & Miller Brewery was built above the John Orth and Germania to form the Minneapolis Brewing southern end of the flats in 1866, a boardinghouse was to and Malting Company in 1890, known today as Grain Belt. provide a home for the brewery workers, mainly German When a centralized brewery was established across the immigrants.[1] They were shortly joined by the Zahler river, the jobs followed, and the breweries on the flats were Brewery built on the other side of the flats in 1874; this abandoned.[2] “Heinrich Brewery building (Minneapolis Brewing Company), foot of Fourth Street, Minneapolis. Photographer unknown, taken in approximately 1895. -

Return to Manassas

CG Fall 04 Fn2_cc 8/28/04 10:43 AM Page 4 NEWS CLOSEUP RETURN TO MANASSAS Saved from Development, a Battlefield Restored Sixteen years ago, subdivision developers began tearing up the land near the site of Robert E. Lee’s COMMON GROUND RE- summer 1862 headquarters, a large tract next to Manassas National Battlefield whose woods and VAMPS ONLINE depressions once hid thousands of troops. The outcry was so loud that Congress seized the land. By PRESENCE Common Ground that time, over 100 acres had been leveled. has just re-vamped Today, as a result of an ambitious restoration—and an unusual turn of events—the terrain looks very much as it did its online pres- when Union and Confederate forces clashed 142 years ago. The land has been restored to within a foot of its original ence, carrying the magazine’s mes- configuration, along with nearly all the vegetation. The remarkable turnabout hinged on two seemingly unrelated cir- sage to the small cumstances: the construction of the Smithsonian Institution’s new annex to the National Air and Space Museum, and screen in a big way. Now the the court-martial of Union General Fitz-John Porter for cowardice. entire range of The annex was built on wetlands a few miles from Dulles Airport. Under federal law, equivalent acreage had to be news and features created, preferably in the same watershed. The Smithsonian looked to the nearby battlefield. is available elec- tronically, includ- It was a fortunate coincidence. The National Park Service had been trying for years to undo the aborted develop- ing an archive of ment. -

Broadway Bridge (Twentieth Avenue North Bridge) HAER No

Broadway Bridge (Twentieth Avenue North Bridge) HAER No. MfcI-2 Spanning the Mississippi River at Broadway Street • Minneapolis Hennepin County LLf\r o Minnesota nnb K. 27- M 0- PHOTOGRAPHS • WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA Historic American Engineering Record Rocky Mountain Regional Office National Park Service Department of the Interior P.O. Box 25287 Denver, Colorado 80225 HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD Broadway Bridge (Twentieth Avenue North Bridge) HAER No. MN-2 Location: Spanning the Mississippi River at Broadway Street Minneapolis, Hennepin County, Minnesota UTM: A 15.4982640.478420 B 15.4982660.478200 Quad: Minneapolis South Date of Construction; 1887-1888 (Modified in 1914 and 1950-1951) Present Owner: Hennepin County Hennepin County Government Center Minneapolis, Minnesota Present Use: Vehicular and pedestrian bridge, to be replaced by a new vehicular and pedestrian bridge. Projected date of removal is Spring 1985. One of the four spans is to be retained and serve as a vehicular and pedestrian bridge at a site located approximately one mile down river. Significance: The Broadway Bridge was a four-span, wrought iron and steel, high through Pratt truss and was one of two known remaining decorative truss bridges in Minnesota. The bridge was fabricated by the King Iron and Bridge Company of Cleveland, Ohio. Historian: Bill Jensen, Van Doren-Hazard-Stallings, December 1984 Transmitted by: Jean P. Yearby, HAER, 1985 Broadway Bridge HAER No. MN-2 (page 2) ftl. HISTORY A. NEED FOR THE BRIDGE "Whenever a few men get together in a doggery and decide they want a bridge, they get it" (Col. W.S. King, Minneapolis businessman; Minneapolis Journal, 31 January 1887). -

Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area Historic Buildings

Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area National Park Service New Jersey, Pennsylvania US Department of the Interior Draft Historic Buildings Strategy July 2021 SUMMARY This document provides a strategy that prioritizes funding and preservation efforts for historic buildings within Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area (“the park”) based on historic significance, condition, interpretive value, and potential for adaptive reuse. There are 286 buildings within the park that are listed or eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places and are considered “historic.” Many buildings are found in groupings, such as on a former farmstead where there is a house, outbuildings, and agricultural landscape features such as fields and fencerows. These are referred to as “historic properties” in the Historic Buildings Strategy (HBS). There are 97 historic properties within the park. The number and condition of the buildings exceed the park’s ability to provide for maintenance. This HBS is a tool to assist the National Park Service in making strategic, prioritized maintenance and preservation decisions for the historic properties in the park. In order to determine which properties to include in the plan and which priority to assign to each property, each was evaluated for historical significance, the physical condition of buildings, and their interpretive value as it relates to their historic context. The HBS assigns a priority to each property—A, B, C, or D. Each category and identifies the types of treatments that would be appropriate under each category. The HBS does not prescribe specific treatments (e.g., specific repair and maintenance work), funding mechanisms, or uses for the property.