Opioid Managementtm a Medical Journal for Proper and Adequate Use

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biased Versus Partial Agonism in the Search for Safer Opioid Analgesics

molecules Review Biased versus Partial Agonism in the Search for Safer Opioid Analgesics Joaquim Azevedo Neto 1 , Anna Costanzini 2 , Roberto De Giorgio 2 , David G. Lambert 3 , Chiara Ruzza 1,4,* and Girolamo Calò 1 1 Department of Biomedical and Specialty Surgical Sciences, Section of Pharmacology, University of Ferrara, 44121 Ferrara, Italy; [email protected] (J.A.N.); [email protected] (G.C.) 2 Department of Morphology, Surgery, Experimental Medicine, University of Ferrara, 44121 Ferrara, Italy; [email protected] (A.C.); [email protected] (R.D.G.) 3 Department of Cardiovascular Sciences, Anesthesia, Critical Care and Pain Management, University of Leicester, Leicester LE1 7RH, UK; [email protected] 4 Technopole of Ferrara, LTTA Laboratory for Advanced Therapies, 44122 Ferrara, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected] Academic Editor: Helmut Schmidhammer Received: 23 July 2020; Accepted: 23 August 2020; Published: 25 August 2020 Abstract: Opioids such as morphine—acting at the mu opioid receptor—are the mainstay for treatment of moderate to severe pain and have good efficacy in these indications. However, these drugs produce a plethora of unwanted adverse effects including respiratory depression, constipation, immune suppression and with prolonged treatment, tolerance, dependence and abuse liability. Studies in β-arrestin 2 gene knockout (βarr2( / )) animals indicate that morphine analgesia is potentiated − − while side effects are reduced, suggesting that drugs biased away from arrestin may manifest with a reduced-side-effect profile. However, there is controversy in this area with improvement of morphine-induced constipation and reduced respiratory effects in βarr2( / ) mice. Moreover, − − studies performed with mice genetically engineered with G-protein-biased mu receptors suggested increased sensitivity of these animals to both analgesic actions and side effects of opioid drugs. -

Methadone Hydrochloride Tablets, USP) 5 Mg, 10 Mg Rx Only

ROXANE LABORATORIES, INC. Columbus, OH 43216 DOLOPHINE® HYDROCHLORIDE CII (Methadone Hydrochloride Tablets, USP) 5 mg, 10 mg Rx Only Deaths, cardiac and respiratory, have been reported during initiation and conversion of pain patients to methadone treatment from treatment with other opioid agonists. It is critical to understand the pharmacokinetics of methadone when converting patients from other opioids (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION). Particular vigilance is necessary during treatment initiation, during conversion from one opioid to another, and during dose titration. Respiratory depression is the chief hazard associated with methadone hydrochloride administration. Methadone's peak respiratory depressant effects typically occur later, and persist longer than its peak analgesic effects, particularly in the early dosing period. These characteristics can contribute to cases of iatrogenic overdose, particularly during treatment initiation and dose titration. In addition, cases of QT interval prolongation and serious arrhythmia (torsades de pointes) have been observed during treatment with methadone. Most cases involve patients being treated for pain with large, multiple daily doses of methadone, although cases have been reported in patients receiving doses commonly used for maintenance treatment of opioid addiction. Methadone treatment for analgesic therapy in patients with acute or chronic pain should only be initiated if the potential analgesic or palliative care benefit of treatment with methadone is considered and outweighs the risks. Conditions For Distribution And Use Of Methadone Products For The Treatment Of Opioid Addiction Code of Federal Regulations, Title 42, Sec 8 Methadone products when used for the treatment of opioid addiction in detoxification or maintenance programs, shall be dispensed only by opioid treatment programs (and agencies, practitioners or institutions by formal agreement with the program sponsor) certified by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and approved by the designated state authority. -

Information to Users

The direct and modulatory antinociceptive actions of endogenous and exogenous opioid delta agonists Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Vanderah, Todd William. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 04/10/2021 00:14:57 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/187190 INFORMATION TO USERS This ~uscript }las been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely. event that the author did not send UMI a complete mannscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginnjng at the upper left-hand comer and contimJing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. -

Opioid Analgesics These Are General Guidelines

Adult Opioid Reference Guide June 2012 Opioid Analgesics These are general guidelines. Patient care requires individualization based on patient needs and responses. Lower doses should be used initially, then titrated up to achieve pain relief, especially if the patient has not been taking opioids for the past week (opioid naïve). Patients who have been taking scheduled opioids for at least the previous 5 days may be considered “opioid tolerant”. These patients may require higher doses for analgesia. Drug # Route Starting Dose Onset Peak Duration Metabolism Half Life Comments (Adults > 50 Kg) Buprenorphine Trans- 5 mcg/hr q 7 DAYS 17 hr 60 hr 7 DAYS Liver 26 hr Maximum dose = 20 mcg/hr patch dermal Extensively metabolized by CYP3A4 enzymes – watch for Example: Butrans® drug interactions Transdermal patches are not available at UIHC Codeine PO 30 - 60 mg q 4 hr 30 min 1½ hr 6 hr Liver 2 - 4 hr Oral not recommended first-line therapy. Some patients cannot metabolize codeine to active morphine. Fentanyl IM 5 mcg/Kg q 1 - 2 hr 7 - 8 min 20 - 50 min 1 - 2 hr Liver 1 - 6 hr* Give IV slowly over several minutes to prevent chest wall IV 0.25 - 1 mcg/Kg as Immediate 1 - 5 min 30 - 60 min rigidity SQ needed Refer to the formulary for administration and monitoring. May be used in patients with renal impairment as it has no active metabolites. Accumulates in adipose tissue with continuous infusion. Trans- 25 mcg/hr 12 - 24 hr 24 hr 48 - 72 hr Transdermal should NOT be used to treat acute pain. -

Opioid Powders Page: 1 of 9

Federal Employee Program® 1310 G Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20005 202.942.1000 Fax 202.942.1125 5.70.64 Section: Prescription Drugs Effective Date: April 1, 2020 Subsection: Analgesics and Anesthetics Original Policy Date: October 20, 2017 Subject: Opioid Powders Page: 1 of 9 Last Review Date: March 13, 2020 Opioid Powders Description Buprenorphine Powder, Butorphanol Powder, Codeine Powder, Hydrocodone Powder, Hydromorphone Powder, Levorphanol Powder, Meperidine Powder, Methadone Powder, Morphine Powder, Oxycodone Powder, Oxymorphone Powder Background Pharmacy compounding is an ancient practice in which pharmacists combine, mix or alter ingredients to create unique medications that meet specific needs of individual patients. Some examples of the need for compounding products would be: the dosage formulation must be changed to allow a person with dysphagia (trouble swallowing) to have a liquid formulation of a commercially available tablet only product, or to obtain the exact strength needed of the active ingredient, to avoid ingredients that a particular patient has an allergy to, or simply to add flavoring to medication to make it more palatable. Buprenorphine, butorphanol, codeine, hydrocodone, hydromorphone, levorphanol, meperidine, methadone, morphine, oxycodone, and oxymorphone powders are opioid drugs that are used for pain control. The intent of the criteria is to provide coverage consistent with product labeling, FDA guidance, standards of medical practice, evidence-based drug information, and/or published guidelines. Because of the risks of addiction, abuse, and misuse with opioids, even at recommended doses, and because of the greater risks of overdose and death (1-15). Regulatory Status 5.70.64 Section: Prescription Drugs Effective Date: April 1, 2020 Subsection: Analgesics and Anesthetics Original Policy Date: October 20, 2017 Subject: Opioid Powders Page: 2 of 9 FDA-approved indications: 1. -

Pain Management After Elective Shoulder Surgery: a Randomized Quantitative Study Comparing Hydromorphone with Piritramide

Case Report J Anest & Inten Care Med Volume 9 Issue 4 - October 2019 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Hermann Prossinger DOI: 10.19080/JAICM.2019.09.555768 Pain Management After Elective Shoulder Surgery: A Randomized Quantitative Study Comparing Hydromorphone With Piritramide Boesmueller S1, Gerstorfer I1, Steiner M1, Prossinger H2*, Fialka C1 and Steltzer H1, 3 1AUVA Meidling, Austria 2Department for Evolutionary Anthropology, University of Vienna, Austria 3Sigmund Freud University, Austria Submission: September 25, 2019; Published: October 11, 2019 *Corresponding author: Hermann Prossinger, Department for Evolutionary Anthropology, Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria Abstract Background: Postoperative pain management plays an important role in elective shoulder surgery. Several methods have been investigated so far. The aim of this randomized quantitative study is to compare two frequently used postoperative pain regimes (hydromorphone versus piritramide) regarding onset and duration after the effectiveness of the single-shot interscalene block has diminished. Methods: All patients who underwent elective shoulder surgery at our institution agreed to participate in this study. Upon admission patients were assigned membership to group A (hydromorphone) or group B (piritramide) according to the patient number (which ensured randomization). Pain assessment was performed using the numeric rating scale (NRS). For statistical analyses the techniques of maximum likelihood (ML) estimation were used. Results: Of the 48 patients aged 18–89 years included in this study, 25 were in group A and 23 in group B. Of these 48, 21 in each group registered pain levels above threshold at least once. Shoulder surgery was performed 45 times in an arthroscopic and 3 times in an open technique. -

Radiolabelled Molecules for Brain Imaging with PET and SPECT • Peter Brust Radiolabelled Molecules for Brain Imaging with PET and SPECT

Radiolabelled Molecules for Brain Imaging with PET and SPECT Radiolabelled • Peter Brust Molecules for Brain Imaging with PET and SPECT Edited by Peter Brust Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Molecules www.mdpi.com/journal/molecules Radiolabelled Molecules for Brain Imaging with PET and SPECT Radiolabelled Molecules for Brain Imaging with PET and SPECT Editor Peter Brust MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade • Manchester • Tokyo • Cluj • Tianjin Editor Peter Brust Department of Neuroradiopharmaceuticals, Institute of Radiopharmaceutical Cancer Research, Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf Germany Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Molecules (ISSN 1420-3049) (available at: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/molecules/special issues/PET SPECT). For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Article Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-03936-720-7 (Hbk) ISBN 978-3-03936-721-4 (PDF) c 2020 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book as a whole is distributed by MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. Contents About the Editor .............................................. vii Preface to ”Radiolabelled Molecules for Brain Imaging with PET and SPECT” ........ -

Enkephalin Degradation in Serum of Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases

Pharmacological Reports 71 (2019) 42–47 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Pharmacological Reports journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/pharep Original article Enkephalin degradation in serum of patients with inflammatory bowel diseases a, a b Beata Wilenska *, Dagmara Tymecka , Marcin Włodarczyk , b c Aleksandra Sobolewska-Włodarczyk , Maria Wisniewska-Jarosinska , d e b a,d, Jolanta Dyniewicz , Árpád Somogyi , Jakub Fichna , Aleksandra Misicka * a Faculty of Chemistry, Biological and Chemical Research Centre, University of Warsaw, Warszawa, Poland b Department of Biochemistry, Medical University of Lodz, Łódz, Poland c Department of Gastroenterology, Medical University of Lodz, Łódz, Poland d Department of Neuropeptides, Mossakowski Medical Research Centre Polish Academy of Science, Warszawa, Poland e Campus Chemical Instrumentation Centre (CCIC), The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Article history: Background: Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are a group of chronic and recurrent gastrointestinal Received 18 April 2018 disorders that are difficult to control. Recently, a new IBD therapy based on the targeting of the Received in revised form 10 June 2018 endogenous opioid system has been proposed. Consequently, due to the fact that endogenous Accepted 1 August 2018 enkephalins have an anti-inflammatory effect, we aimed at investigating the degradation of serum Available online 2 August 2018 enkephalin (Met- and Leu-enkephalin) in patients with IBD. Methods: Enkephalin degradation in serum of patients with IBD was characterized using mass Keywords: spectrometry methods. Calculated half-life (T1/2) of enkephalins were compared and correlated with the Inflammatory bowel diseases disease type and gender of the patients. -

Evidence Review F: Opioids for Pain Relief After Caesarean Birth

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence FINAL Caesarean birth [F] Opioids for pain relief after caesarean birth NICE guideline NG192 Evidence review March 2021 Final This evidence review was developed by the National Guideline Alliance which is a part of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists FINAL Contents Disclaimer The recommendations in this guideline represent the view of NICE, arrived at after careful consideration of the evidence available. When exercising their judgement, professionals are expected to take this guideline fully into account, alongside the individual needs, preferences and values of their patients or service users. The recommendations in this guideline are not mandatory and the guideline does not override the responsibility of healthcare professionals to make decisions appropriate to the circumstances of the individual patient, in consultation with the patient and/or their carer or guardian. Local commissioners and/or providers have a responsibility to enable the guideline to be applied when individual health professionals and their patients or service users wish to use it. They should do so in the context of local and national priorities for funding and developing services, and in light of their duties to have due regard to the need to eliminate unlawful discrimination, to advance equality of opportunity and to reduce health inequalities. Nothing in this guideline should be interpreted in a way that would be inconsistent with compliance with those duties. NICE guidelines cover health and care in England. Decisions on how they apply in other UK countries are made by ministers in the Welsh Government, Scottish Government, and Northern Ireland Executive. -

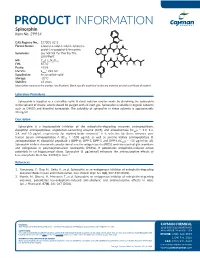

PRODUCT INFORMATION Spinorphin Item No

PRODUCT INFORMATION Spinorphin Item No. 29914 NH CAS Registry No.: 137201-62-8 Formal Name: L-leucyl-L-valyl-L-valyl-L-tyrosyl-L- O H O N prolyl-L-tryptophyl-L-threonine N OH O N H Synonyms: Leu-Val-Val-Tyr-Pro-Trp-Thr, O OH H LVVYPWT O O N MF: C45H64N8O10 N N O FW: 877.0 H H NH2 Purity: ≥95% UV/Vis.: λmax: 222 nm Supplied as: A crystalline solid Storage: -20°C OH Stability: ≥2 years Information represents the product specifications. Batch specific analytical results are provided on each certificate of analysis. Laboratory Procedures Spinorphin is supplied as a crystalline solid. A stock solution may be made by dissolving the spinorphin in the solvent of choice, which should be purged with an inert gas. Spinorphin is soluble in organic solvents such as DMSO and dimethyl formamide. The solubility of spinorphin in these solvents is approximately 30 mg/ml. Description Spinorphin is a heptapeptide inhibitor of the enkephalin-degrading enzymes aminopeptidase, dipeptidyl aminopeptidase, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), and enkephalinase (IC50s = 3.3, 1.4, 2.4, and 10 µg/ml, respectively, for monkey brain enzymes).1 It is selective for these enzymes over human serum aminopeptidase A (IC50 = >100 µg/ml), as well as porcine kidney aminopeptidase B, aminopeptidase M, dipeptidyl peptidase 1 (DPP-1), DPP-2, DPP-3, and DPP-4 (IC50s = >55 µg/ml for all). Spinorphin inhibits chemotaxis, production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and exocytosis of glucuronidase and collagenase in polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs). It potentiates enkephalin-induced action potentials in rat hippocampal slices. -

Pre - PA Allowance Age 12 Years of Age Or Older – Ultracet (Tramadol and Acetaminophen) and Codeine/APAP Products

OPIOID IR COMBO DRUGS Apadaz* (benzhydrocodone-acetaminophen), Codeine-acetaminophen, Dvorah* (dihydrocodeine-caffeine-acetaminophen*), Hydrocodone-acetaminophen, Hydrocodone- acetaminophen solution 10-325mg*, Hydrocodone-ibuprofen, Nalocet* (oxycodone- acetaminophen*), Oxycodone-acetaminophen, Oxycodone-aspirin, Oxycodone-ibuprofen, Primlev*/Prolate* (oxycodone-acetaminophen*), Tramadol-acetaminophen, Trezix (dihydrocodeine-caffeine-acetaminophen) *Prior authorization for certain non-covered formulations applies only to formulary exceptions Pre - PA Allowance Age 12 years of age or older – Ultracet (tramadol and acetaminophen) and Codeine/APAP products Quantity Patients 18 years or older will be able to fill the Pre-PA Allowance after they have filled an initial 7 day supply of IR opioid therapy or if they have been on IR or ER opioid therapy in the last 180 days Patients age 17 and under will require a PA after they have filled a 3 day supply of the Pre- PA Allowance Patients with opioid addiction treatment or methadone in the last 30 days will not be eligible for Pre-PA Allowance Immediate Release Tablets or Capsules ≤ 50 MME/day Medication Strength Quantity Limit Codeine/APAP soln 120-12 mg/5 mL Hydrocodone/APAP soln 7.5/325 mg/15 mL 5400 mL per 90 days Hydrocodone/APAP elixir 10/300 mg/15 mL Oxycodone/APAP soln 5-325 mg/5 mL 3000 mL per 90 days Hydrocodone/ibuprofen 5/200 mg, 7.5/200 mg, 10/200 mg 270 units per 90 days Oxycodone/ibuprofen 5/400 mg Oxycodone/APAP 10/325 mg Codeine/APAP 60/300 mg Hydrocodone/APAP 7.5/300 mg, 7.5/325 -

ID-75-77 If the United States Is to Develop an Effective International

UN1TED STATES REPO@F !FfyT’?f?8T CONGRESSOfb7J+ JUL 3 I ?wl llillllllllllillll1lll1lll~llll~~l LM096967 “-...-. x-- If The Un’ited States Is To Develop An Effective International Narcotics Control Program, Much More Must Be Done In this Feport GAO examines U.S. diplomatic actions and other activities aimed at halting International production and trafficking of illicit narcotics and at stopping their flow into the United States. BY THE COMPTROLLER GENERAL OF THE UNITED STATES @ ID-75-77 COMPTROLLER GENERAL OF THE UNITED STATES WASHINGTON. D.C. X’S48 E-175425 To the President of the Senate and the br Speaker of the House of Representatives This report examines U.S. international narcotics control efforts and discusses improvements needed in opera- tions, activities, and related policies and objectives. We made our review pursuant to the Budget and Accounting Act, 1921 (31 U.S.C. 53), and the Accounting and Auditing Act of 1950 (31 U.S.C. 67). We are sending copies of this report to the Director, Office of Management and Budget; the Secretary of State; the Attorney General; and the Administrator, Agency for Inter- national Development. Comptroller General of the United States r- t Contents Page DIGEST i CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND General overview Funding Cabinet Committee Scope of review 2 U.S. OPIUM POLICY 8 U.S. opium policy unclear 8 Evolution of an alleged opium shortage 10 Increasing medicinal opiate supplies 13 Agency comments and our evaluation 18 Conclusions 22 Recommendation 22 3 ILLICIT NARCOTICS PRODUCTION AND TRAFFICKING