Species Description Taxonomy Distribution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Body Condition Assessment – As a Welfare and Management Assessment Tool for Radiated Tortoises (Astrochelys Radiata)

Body condition assessment – as a welfare and management assessment tool for radiated tortoises (Astrochelys radiata) Hullbedömning - som ett verktyg för utvärdering av välfärd och skötsel av strålsköldpadda (Astrochelys radiata) Linn Lagerström Independent project • 15 hp Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, SLU Department of Animal Environment and Health Programme/Education Uppsala 2020 2 Body condition assessment – as a welfare and management tool for radiated tortoises (Astrochelys radiata) Hullbedömning - som ett verktyg för utvärdering av välfärd och skötsel av strålsköldpadda (Astrochelys radiata) Linn Lagerström Supervisor: Lisa Lundin, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Department of Animal Environment and Health Examiner: Maria Andersson, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Department of Animal Environment and Health Credits: 15 hp Level: First cycle, G2E Course title: Independent project Course code: EX0894 Programme/education: Course coordinating dept: Department of Aquatic Sciences and Assessment Place of publication: Uppsala Year of publication: 2020 Cover picture: Linn Lagerström Keywords: Tortoise, turtle, radiated tortoise, Astrochelys radiata, Geochelone radiata, body condition indices, body condition score, morphometrics Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Faculty of Natural Resources and Agricultural Sciences Department of Animal Environment and Health 3 Publishing and archiving Approved students’ theses at SLU are published electronically. As a student, you have the copyright to your own work and need to approve the electronic publishing. If you check the box for YES, the full text (pdf file) and metadata will be visible and searchable online. If you check the box for NO, only the metadata and the abstract will be visiable and searchable online. Nevertheless, when the document is uploaded it will still be archived as a digital file. -

English and French Cop17 Inf

Original language: English and French CoP17 Inf. 36 (English and French only / Únicamente en inglés y francés / Seulement en anglais et français) CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________________ Seventeenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties Johannesburg (South Africa), 24 September – 5 October 2016 JOINT STATEMENT REGARDING MADAGASCAR’S PLOUGHSHARE / ANGONOKA TORTOISE 1. This document has been submitted by the United States of America at the request of the Wildlife Conservation Society, Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust, Turtle Survival Alliance, and The Turtle Conservancy, in relation to agenda item 73 on Tortoises and freshwater turtles (Testudines spp.)*. 2. This species is restricted to a limited range in northwestern Madagascar. It has been included in CITES Appendix I since 1975 and has been categorized as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species since 2008. There has been a significant increase in the level of illegal collection and trafficking of this species to supply the high end pet trade over the last 5 years. 3. Attached please find the joint statement regarding Madagascar’s Ploughshare/Angonoka Tortoise, which is considered directly relevant to Document CoP17 Doc. 73 on tortoises and freshwater turtles. * The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CITES Secretariat (or the United Nations Environment Programme) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. -

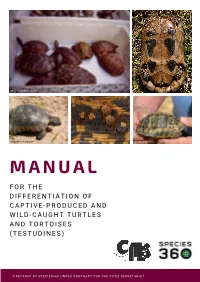

Manual for the Differentiation of Captive-Produced and Wild-Caught Turtles and Tortoises (Testudines)

Image: Peter Paul van Dijk Image:Henrik Bringsøe Image: Henrik Bringsøe Image: Andrei Daniel Mihalca Image: Beate Pfau MANUAL F O R T H E DIFFERENTIATION OF CAPTIVE-PRODUCED AND WILD-CAUGHT TURTLES AND TORTOISES (TESTUDINES) PREPARED BY SPECIES360 UNDER CONTRACT FOR THE CITES SECRETARIAT Manual for the differentiation of captive-produced and wild-caught turtles and tortoises (Testudines) This document was prepared by Species360 under contract for the CITES Secretariat. Principal Investigators: Prof. Dalia A. Conde, Ph.D. and Johanna Staerk, Ph.D., Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, https://www.species360.orG Authors: Johanna Staerk1,2, A. Rita da Silva1,2, Lionel Jouvet 1,2, Peter Paul van Dijk3,4,5, Beate Pfau5, Ioanna Alexiadou1,2 and Dalia A. Conde 1,2 Affiliations: 1 Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, www.species360.orG,2 Center on Population Dynamics (CPop), Department of Biology, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark, 3 The Turtle Conservancy, www.turtleconservancy.orG , 4 Global Wildlife Conservation, globalwildlife.orG , 5 IUCN SSC Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, www.iucn-tftsG.org. 6 Deutsche Gesellschaft für HerpetoloGie und Terrarienkunde (DGHT) Images (title page): First row, left: Mixed species shipment (imaGe taken by Peter Paul van Dijk) First row, riGht: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with damaGe of the plastron (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, left: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with minor damaGe of the carapace (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, middle: Ticks on tortoise shell (Amblyomma sp. in Geochelone pardalis) (imaGe taken by Andrei Daniel Mihalca) Second row, riGht: Testudo graeca with doG bite marks (imaGe taken by Beate Pfau) Acknowledgements: The development of this manual would not have been possible without the help, support and guidance of many people. -

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises Edited by Ian R. Swingland and Michael W. Klemens IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group and The Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) No. 5 IUCN—The World Conservation Union IUCN Species Survival Commission Role of the SSC 3. To cooperate with the World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC) The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is IUCN's primary source of the in developing and evaluating a data base on the status of and trade in wild scientific and technical information required for the maintenance of biological flora and fauna, and to provide policy guidance to WCMC. diversity through the conservation of endangered and vulnerable species of 4. To provide advice, information, and expertise to the Secretariat of the fauna and flora, whilst recommending and promoting measures for their con- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna servation, and for the management of other species of conservation concern. and Flora (CITES) and other international agreements affecting conser- Its objective is to mobilize action to prevent the extinction of species, sub- vation of species or biological diversity. species, and discrete populations of fauna and flora, thereby not only maintain- 5. To carry out specific tasks on behalf of the Union, including: ing biological diversity but improving the status of endangered and vulnerable species. • coordination of a programme of activities for the conservation of biological diversity within the framework of the IUCN Conserva- tion Programme. Objectives of the SSC • promotion of the maintenance of biological diversity by monitor- 1. -

The Use of Extant Non-Indigenous Tortoises As a Restoration Tool to Replace Extinct Ecosystem Engineers

OPINION ARTICLE The Use of Extant Non-Indigenous Tortoises as a Restoration Tool to Replace Extinct Ecosystem Engineers Christine J. Griffiths,1,2,3,4 Carl G. Jones,3,5 Dennis M. Hansen,6 Manikchand Puttoo,7 Rabindra V. Tatayah,3 Christine B. Muller,¨ 2,∗ andStephenHarris1 Abstract prevent the extinction and further degradation of Round We argue that the introduction of non-native extant tor- Island’s threatened flora and fauna. In the long term, the toises as ecological replacements for extinct giant tortoises introduction of tortoises to Round Island will lead to valu- is a realistic restoration management scheme, which is able management and restoration insights for subsequent easy to implement. We discuss how the recent extinctions larger-scale mainland restoration projects. This case study of endemic giant Cylindraspis tortoises on the Mascarene further highlights the feasibility, versatility and low-risk Islands have left a legacy of ecosystem dysfunction threat- nature of using tortoises in restoration programs, with par- ening the remnants of native biota, focusing on the island ticular reference to their introduction to island ecosystems. of Mauritius because this is where most has been inferred Overall, the use of extant tortoises as replacements for about plant–tortoise interactions. There is a pressing need extinct ones is a good example of how conservation and to restore and preserve several Mauritian habitats and restoration biology concepts applied at a smaller scale can plant communities that suffer from ecosystem dysfunction. be microcosms for more grandiose schemes and addresses We discuss ongoing restoration efforts on the Mauritian more immediate conservation priorities than large-scale offshore Round Island, which provide a case study high- ecosystem rewilding projects. -

Aldabrachelys Arnoldi (Bour 1982) – Arnold's Giant Tortoise

Conservation Biology of Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises: A Compilation ProjectTestudinidae of the IUCN/SSC — AldabrachelysTortoise and Freshwater arnoldi Turtle Specialist Group 028.1 A.G.J. Rhodin, P.C.H. Pritchard, P.P. van Dijk, R.A. Saumure, K.A. Buhlmann, J.B. Iverson, and R.A. Mittermeier, Eds. Chelonian Research Monographs (ISSN 1088-7105) No. 5, doi:10.3854/crm.5.028.arnoldi.v1.2009 © 2009 by Chelonian Research Foundation • Published 18 October 2009 Aldabrachelys arnoldi (Bour 1982) – Arnold’s Giant Tortoise JUSTIN GERLACH 1 1133 Cherry Hinton Road, Cambridge CB1 7BX, United Kingdom [[email protected]] SUMMARY . – Arnold’s giant tortoise, Aldabrachelys arnoldi (= Dipsochelys arnoldi) (Family Testudinidae), from the granitic Seychelles, is a controversial species possibly distinct from the Aldabra giant tortoise, A. gigantea (= D. dussumieri of some authors). The species is a morphologi- cally distinctive morphotype, but has so far not been genetically distinguishable from the Aldabra tortoise, and is considered synonymous with that species by many researchers. Captive reared juveniles suggest that there may be a genetic basis for the morphotype and more detailed genetic work is needed to elucidate these relationships. The species is the only living saddle-backed tortoise in the Seychelles islands. It was apparently extirpated from the wild in the 1800s and believed to be extinct until recently purportedly rediscovered in captivity. The current population of this morphotype is 23 adults, including 18 captive adult males on Mahé Island, 5 adults recently in- troduced to Silhouette Island, and one free-ranging female on Cousine Island. Successful captive breeding has produced 138 juveniles to date. -

(Geochelone Pardalis) on Farmland in the Nama-Karoo

THE STATUS AND ECOLOGY OF THE LEOPARD TORTOISE (GEOCHELONE PARDALIS) ON FARMLAND IN THE NAMA-KAROO MEGAN KAY McMASTER Submitted in fulfilment ofthe academic requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE School ofBotany and Zoology University ofNatal Pieterrnaritzburg March 2001 Preface The experimental work described in this dissertation was carried out in the School of Botany and Zoology, University ofNatal, Pietermaritzburg, from November 1997 to March 2001, under the supervision ofDr. Colleen T. Downs. This study is the original work ofthe author and has not been submitted in any form for any diploma or degree to another university. Where use has been made ofthe work of others, it is duly acknowledged in the text. Each chapter is written in the format ofthe journal it has been submitted to. ..fj~K'. Megan Kay McMaster Pietermaritzburg March 2001 11 This thesis is dedicated to myfather, the late Eric Ralph McMaster, for his constant encouragement and beliefin me, and to my brother, the late Gregory CIifton McMaster,for always making me smile. III Abstract The Family Testudinidae (Suborder Cryptodira) is represented by 40 species worldwide and reaches its greatest diversity in southern Africa, where 14 species occur (33%), ten of which are endemic to the subcontinent. Despite the strong representation ofterrestrial tortoise species in southern Africa, and the importance ofthe Karoo as a centre of endemism ofthese tortoise species, there is a paucity ofecological information for most tortoise species in South Africa. With chelonians being protected in < 15% ofall southern African reserves it is necessary to find out more about the ecological requirements, status, population dynamics and threats faced by South African tortoise species to enable the formulation ofeffective conservation measures. -

SC73 Doc. 24.1

Original language: English SC73 Doc. 24.1 CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ___________________ Seventy-third meeting of the Standing Committee Online, 5-7 May 2021 Species specific matters Tortoises and freshwater turtles (Testudines spp.) REPORT OF THE SECRETARIAT 1. This document has been prepared by the Secretariat. 2. At its 18th meeting (CoP18, Geneva, 2019), the Conference of the Parties adopted inter alia Decisions 18.286 and 18.287 on Tortoises and freshwater turtles (Testudines spp.), as follows: 18.286 Directed to Madagascar Madagascar should: a) review its implementation of Resolution Conf. 11.9 (Rev. CoP18) on Conservation of and trade in tortoises and freshwater turtles; and b) report to the 73rd meeting of the Standing Committee on its implementation of Resolution Conf. 11.9 (Rev. CoP18), including in its report, information on any seizures, arrests, prosecutions and convictions secured as a result of activities implemented to address illegal trade in tortoises from Madagascar. 18.287 Directed to the Standing Committee The Standing Committee shall review the report from Madagascar in accordance with Decision 18.286, and any recommendations from the Secretariat, and consider if any further measures need to be implemented by Madagascar to address illegal trade in tortoises as it affects the Party. 3. Pursuant to Decision 18.286, Madagascar submitted a report on its implementation of Resolution Conf. 11.9 (Rev. CoP18) on Conservation of and trade in tortoises and freshwater turtles to the Secretariat on 30 June 2020. The report, available as document SC73 Doc. 24.2, includes as an Annex the Regional strategy to combat trafficking in radiated tortoises (Astrochelys radiata) in the Atsimo-Andrefana region of Madagascar (Stratégie régionale de lutte contre le trafic de tortues radiées « Astrochelys radiata » dans la région Atismo Andrefana – in French only). -

RADIATED TORTOISE Testudines Family: Testudinidae Genus: Astrochelys Species: Radiata

RADIATED TORTOISE Testudines Family: Testudinidae Genus: Astrochelys Species: radiata Range: Southern Madagascar Habitat: dry regions of brush, thorn forests, and woodlands Niche: Terrestrial, diurnal, herbivorous Wild diet: grasses, fruit and succulent plants Zoo diet: Life Span: (Wild) 40 – 50 years (Captivity) up to 100 years Sexual dimorphism: Male has longer tail and more protruding scutes, the notch in the plastron beneath the tail is more noticeable. Location in SF Zoo: Children’s Zoo, Koret Animal Resource Center APPEARANCE & PHYSICAL ADAPTATIONS: The radiated tortoise has a high-domed carapace with yellow lines running down from the center of the dark plate of the shell. This pattern appears to radiate from the shell, hence the name, radiated tortoise. The radiating lines extend down the scutes, the shell’s plates. Its legs and feet are yellow as is its head, except for a black patch on top. This Weight: 35 lbs tortoise has a blunt head, and elephantine feet. Juveniles are black and off- white when they hatch, but quickly develop the adult's striking coloration. Length: 16 in Their strong legs and round, stumpy feet made for walking on land. Their front limbs are flattened with well-developed muscle and sharp claw-like scales adapted for burrowing. The shell is supplied with blood vessels and nerves so like other tortoises it can feel when being touched. STATUS & CONSERVATION The radiated tortoise is listed in Appendix I of CITES. These tortoises are critically endangered due to loss of habitat, being poached for food, and being over exploited in the pet trade. Some Chinese will pay the equivalent of $50 for a radiated tortoise to eat (they are also believed to have aphrodisiac properties). -

Branding Ploughshare Tortoises

N E W S Critically Endangered Ploughshare Tortoises: the smugglers, a Malagasy woman, was imprisoned, while the shells branded to reduce demand RWKHUD7KDLPDQZDVUHOHDVHGRQEDLO 6KHSKHUG These cases exemplify the urgent need for enforcement agencies to take the illegal trade in this species seriously. he Ploughshare Tortoise Astrochelys yniphora Reduced demand for the species in the international pet is highly threatened by persistent demand in trade and increased effective enforcement measures are the black market pet trade. As a result, its essential to end the decline of this species. numbers in the wild have been drastically The Turtle Conservancy, whose mission includes reduced to approximately 400 adult maintaining colonies of threatened and endangered specimens. Assessed as being Critically Endangered in T tortoises and freshwater turtles, aims to engrave Red List of Threatened Species the IUCN , these tortoises LGHQWL¿FDWLRQ PDUNV RQ DOO 3ORXJKVKDUH 7RUWRLVHV LQ are stolen by poachers who sell them to unscrupulous captive-breeding programmes and those remaining in traders, mainly in South-east Asia. WKHZLOG2Q-DQXDU\WKH7XUWOH&RQVHUYDQF\¶V The Ploughshare Tortoise is endemic to the Baly Behler Chelonian Center in Ventura County, USA, Bay area in north-western Madagascar (Leuteritz and branded the shells of two Ploughshare Tortoises that 3HGURQR ZKHUHLWLVWRWDOO\SURWHFWHGE\ODZ7KH KDGEHHQÀRZQLQIURP7DLZDQZKHUHWKH\ZHUHVHL]HG species is also listed in Appendix I of the Convention on LQ $QRQ 6RPH %XUPHVH 6WDUUHG International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna Tortoises Geochelone platynota &,7(6 $SSHQGL[ , DQG)ORUD &,7(6 PDNLQJDQ\LQWHUQDWLRQDOFRPPHUFLDO were similarly marked with the help of the Conservancy trade illegal. Yet demand from some countries, in LQ2FWREHU $QRQ particular Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand, combined with low levels of effective enforcement, continue to References push this striking species towards extinction (Shepherd DQG1LMPDQ6WHQJHOet al $QRQ Los Angeles Times, 14 January. -

Keeping and Breeding Leopard Tortoises (Geochelone Pardalis)

Keeping and breeding Leopard Tortoises Keeping and breeding Leopard Tortoises (Geochelone pardalis). Part 1. Egg-laying, incubation, and care of hatchlings ROBERT BUSTARD HIS captive-breeding/husbandry article on a length of about 15cm (6"). At this time they will Tvery beautiful — indeed magnificent-looking court females assiduously. Females are — tortoise, resulted from a discussion at Council considerably larger, however, before they in October 2001 on the inadequate number of commence breeding with the result that these practical articles on keeping the various species of newly sexually mature males have trouble in reptiles and amphibians being submitted to The mounting them successfully. Although female Herpetological Bulletin. I at once had a `whip leopards take on average a couple of years longer round' getting everyone present to undertake to than males to reach sexual maturity, size/weight is write an article on some topic of their competence. always a much more reliable guide than age in I then asked Council what they wanted me to reptiles and females can be expected to commence write. I think it was Barry Pomfret who actually breeding around a weight of 8kg. `roped me in' for this topic as he said there were a Because of the leopards' highly-domed lot of people keeping 'leopards' these days. Partly carapace males need to be sufficiently large to be I was to blame, as I had said that they were able to successfully mount any given female. `boring', and didn't do much and — insult of Enthusiasm is not enough! As is common in insults — that one would be as good with some tortoises, optimistic males will usually select the garden gnome leopards as with the real thing! largest female on offer. -

TESTUDINIDAE Geochelone Chilensis

n REPTILIA: TESTUDINES: TESTUDINIDAE Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. Ernst, C.H. 1998. Geochelone chilensis. Geochelone chilensis (Gray) Chaco Tortoise Testudo (Gopher) chilensis Gray 1870a: 190. Type locality, "Chili [Chile, South America]. " Restricted to Mendoza. Ar- gentina by Boulenger (1 889) without explanation (see Com- ments). Syntypes, Natural History Museum. London (BMNH), 1947.3.5.8-9, two stuffed juveniles; specimens missing as of August 1998 (fide C.J. McCarthy and C.H. Ernst, see Comments)(not examined by author). Testudo orgentinu Sclater 1870:47 1. See Comments. Testrrdo chilensis: Philippi 1872:68. Testrrrlo (Pamparestrrdo) chilensis: Lindholm 1929:285. Testucin (Chelonoidis) chilensis: Williams 1 950:22. Geochelone chilensis: Williams 1960: 10. First use of combina- tion. Geochelone (Che1onoide.r) chilensis: Auffenberg 197 1 : 1 10. Geochelone donosoharro.si Freiberg 1973533. Type locality, "San Antonio [Oeste], Rio Negro [Province, Argentina]." Ho- lotype, U.S. Natl. Mus. (USNM) 192961, adult male. col- lected by S. Narosky. 22 April 1971 (examined by author). Geochelone petersi Freibeg 197386. Type locality. "Kishka, La Banda. Santiago del Estero [Province, Argentina]." Ho- lotype, USNM 192959. subadult male, collected by J.J. Mar- n cos, 5 May 197 1 (examined by author). Geochelone ootersi: Freiberzm 1973:9 1. E-r errore. Geochelone (Chelonoidis) d1ilensi.s: Auffenberg 1974: 148. MAP. The circle marks the type locality; dots indicate other selected Geochelone ckilensis chilensis: Pritchard 1979:334. records: stars indicate fossil records. Geochelone ckilensis donosoburro.si: Pritchard 1979:335. Chelorroidis chilensis: Bour 1980:546. Geocheloni perersi: Freibeg 1984:30: growth annuli surround the slightly raised vertebral and pleural Chelorioidis donosoharrosi: Cei 1986: 148.