Tang Taizong and His Advisors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kūnqǔ in Practice: a Case Study

KŪNQǓ IN PRACTICE: A CASE STUDY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THEATRE OCTOBER 2019 By Ju-Hua Wei Dissertation Committee: Elizabeth A. Wichmann-Walczak, Chairperson Lurana Donnels O’Malley Kirstin A. Pauka Cathryn H. Clayton Shana J. Brown Keywords: kunqu, kunju, opera, performance, text, music, creation, practice, Wei Liangfu © 2019, Ju-Hua Wei ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my gratitude to the individuals who helped me in completion of my dissertation and on my journey of exploring the world of theatre and music: Shén Fúqìng 沈福庆 (1933-2013), for being a thoughtful teacher and a father figure. He taught me the spirit of jīngjù and demonstrated the ultimate fine art of jīngjù music and singing. He was an inspiration to all of us who learned from him. And to his spouse, Zhāng Qìnglán 张庆兰, for her motherly love during my jīngjù research in Nánjīng 南京. Sūn Jiàn’ān 孙建安, for being a great mentor to me, bringing me along on all occasions, introducing me to the production team which initiated the project for my dissertation, attending the kūnqǔ performances in which he was involved, meeting his kūnqǔ expert friends, listening to his music lessons, and more; anything which he thought might benefit my understanding of all aspects of kūnqǔ. I am grateful for all his support and his profound knowledge of kūnqǔ music composition. Wichmann-Walczak, Elizabeth, for her years of endeavor producing jīngjù productions in the US. -

Cataloguing Chinese Art in the Middle and Late Imperial Eras

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations Spring 2010 Tradition and Transformation: Cataloguing Chinese Art in the Middle and Late Imperial Eras YEN-WEN CHENG University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian Art and Architecture Commons, Asian History Commons, and the Cultural History Commons Recommended Citation CHENG, YEN-WEN, "Tradition and Transformation: Cataloguing Chinese Art in the Middle and Late Imperial Eras" (2010). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 98. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/98 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/98 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tradition and Transformation: Cataloguing Chinese Art in the Middle and Late Imperial Eras Abstract After obtaining sovereignty, a new emperor of China often gathers the imperial collections of previous dynasties and uses them as evidence of the legitimacy of the new regime. Some emperors go further, commissioning the compilation projects of bibliographies of books and catalogues of artistic works in their imperial collections not only as inventories but also for proclaiming their imperial power. The imperial collections of art symbolize political and cultural predominance, present contemporary attitudes toward art and connoisseurship, and reflect emperors’ personal taste for art. The attempt of this research project is to explore the practice of art cataloguing during two of the most important reign periods in imperial China: Emperor Huizong of the Northern Song Dynasty (r. 1101-1125) and Emperor Qianlong of the Qing Dynasty (r. 1736-1795). Through examining the format and content of the selected painting, calligraphy, and bronze catalogues compiled by both emperors, features of each catalogue reveal the development of cataloguing imperial artistic collections. -

The Life and Writings of Xu Hui (627–650), Worthy Consort, at the Early Tang Court

life and writings of xu hui paul w. kroll The Life and Writings of Xu Hui (627–650), Worthy Consort, at the Early Tang Court mong the women poets of the Tang dynasty (618–907) surely the A.best known are Xue Tao 薛濤 (770–832), the literate geisha from Shu 蜀, and the volatile, sometime Daoist priestess Yu Xuanji 魚玄機 (ca. 844–870?). More interesting strictly as a poet than these two fig- ures are Li Ye 李冶 who was active during the late-eighth century and whose eighteen remaining poems show more range and skill than either Xue Tao or Yu Xuanji, and the “Lady of the Flower Stamens” (“Hua- rui furen” 花蕊夫人) whose 157 heptametric quatrains in the “palace” style occupy all of juan 798 in Quan Tang shi 全唐詩, even though she lived in the mid-tenth century and served at the court of the short-lived kingdom of Later Shu 後蜀.1 Far more influential in her day than any of these, though barely two dozen of her poems are now preserved, was the elegant Shangguan Wan’er 上官婉兒 (ca. 664–710), granddaughter of the executed courtier and poet Shangguan Yi 上官儀 (?–665) who had paid the ultimate price for opposing empress Wu Zhao’s 吳曌 (625–705) usurpation of imperial privileges.2 After the execution of Shangguan Yi and other members of his family, Wan’er, then just an infant, was taken into the court as a sort of expiation by empress Wu.3 By the end I should like to thank David R. -

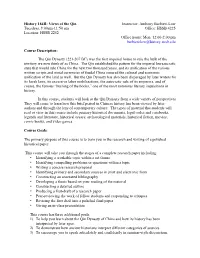

Views of the Qin Instructor: Anthony Barbieri-Low Tuesdays, 9:00Am-11:50 Am Office: HSSB 4225 Location: HSSB 2252 Office Hours: Mon

History 184R: Views of the Qin Instructor: Anthony Barbieri-Low Tuesdays, 9:00am-11:50 am Office: HSSB 4225 Location: HSSB 2252 Office hours: Mon. 12:00-2:00 pm [email protected] Course Description: The Qin Dynasty (221-207 BC) was the first imperial house to rule the bulk of the territory we now think of as China. The Qin established the pattern for the imperial bureaucratic state that would rule China for the next two thousand years, and its unification of the various written scripts and metal currencies of feudal China ensured the cultural and economic unification of the land as well. But the Qin Dynasty has also been disparaged by later writers for its harsh laws, its excessive labor mobilizations, the autocratic rule of its emperors, and of course, the famous “burning of the books,” one of the most notorious literary inquisitions in history. In this course, students will look at the Qin Dynasty from a wide variety of perspectives. They will come to learn how this brief period in Chinese history has been viewed by later authors and through the lens of contemporary culture. The types of material that students will read or view in this course include primary historical documents, legal codes and casebooks, legends and literature, historical essays, archaeological materials, historical fiction, movies, comic books, and video games. Course Goals: The primary purpose of this course is to train you in the research and writing of a polished historical paper. This course will take you through the stages of a complete research paper -

The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Wai Kit Wicky Tse University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Tse, Wai Kit Wicky, "Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier" (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 589. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Abstract As a frontier region of the Qin-Han (221BCE-220CE) empire, the northwest was a new territory to the Chinese realm. Until the Later Han (25-220CE) times, some portions of the northwestern region had only been part of imperial soil for one hundred years. Its coalescence into the Chinese empire was a product of long-term expansion and conquest, which arguably defined the egionr 's military nature. Furthermore, in the harsh natural environment of the region, only tough people could survive, and unsurprisingly, the region fostered vigorous warriors. Mixed culture and multi-ethnicity featured prominently in this highly militarized frontier society, which contrasted sharply with the imperial center that promoted unified cultural values and stood in the way of a greater degree of transregional integration. As this project shows, it was the northwesterners who went through a process of political peripheralization during the Later Han times played a harbinger role of the disintegration of the empire and eventually led to the breakdown of the early imperial system in Chinese history. -

Download File

On A Snowy Night: Yishan Yining (1247-1317) and the Development of Zen Calligraphy in Medieval Japan Xiaohan Du Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2021 © 2021 Xiaohan Du All Rights Reserved Abstract On A Snowy Night: Yishan Yining (1247-1317) and the Development of Zen Calligraphy in Medieval Japan Xiaohan Du This dissertation is the first monographic study of the monk-calligrapher Yishan Yining (1247- 1317), who was sent to Japan in 1299 as an imperial envoy by Emperor Chengzong (Temur, 1265-1307. r. 1294-1307), and achieved unprecedented success there. Through careful visual analysis of his extant oeuvre, this study situates Yishan’s calligraphy synchronically in the context of Chinese and Japanese calligraphy at the turn of the 14th century and diachronically in the history of the relationship between calligraphy and Buddhism. This study also examines Yishan’s prolific inscriptional practice, in particular the relationship between text and image, and its connection to the rise of ink monochrome landscape painting genre in 14th century Japan. This study fills a gap in the history of Chinese calligraphy, from which monk- calligraphers and their practices have received little attention. It also contributes to existing Japanese scholarship on bokuseki by relating Zen calligraphy to religious and political currents in Kamakura Japan. Furthermore, this study questions the validity of the “China influences Japan” model in the history of calligraphy and proposes a more fluid and nuanced model of synthesis between the wa and the kan (Japanese and Chinese) in examining cultural practices in East Asian culture. -

Politics, Classicism, and Medicine During the Eighteenth Century 十八世紀在德川日本 "頌華者" 和 "貶華者" 的 問題 – 以中醫及漢方為主

East Asian Science, Technology and Society: an International Journal DOI 10.1007/s12280-008-9042-9 Sinophiles and Sinophobes in Tokugawa Japan: Politics, Classicism, and Medicine During the Eighteenth Century 十八世紀在德川日本 "頌華者" 和 "貶華者" 的 問題 – 以中醫及漢方為主 Benjamin A. Elman Received: 12 May 2008 /Accepted: 12 May 2008 # National Science Council, Taiwan 2008 Abstract This article first reviews the political, economic, and cultural context within which Japanese during the Tokugawa era (1600–1866) mastered Kanbun 漢 文 as their elite lingua franca. Sino-Japanese cultural exchanges were based on prestigious classical Chinese texts imported from Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1911) China via the controlled Ningbo-Nagasaki trade and Kanbun texts sent in the other direction, from Japan back to China. The role of Japanese Kanbun teachers in presenting language textbooks for instruction and the larger Japanese adaptation of Chinese studies in the eighteenth century is then contextualized within a new, socio-cultural framework to understand the local, regional, and urban role of the Confucian teacher–scholar in a rapidly changing Tokugawa society. The concluding part of the article is based on new research using rare Kanbun medical materials in the Fujikawa Bunko 富士川文庫 at Kyoto University, which show how some increasingly iconoclastic Japanese scholar–physicians (known as the Goiha 古醫派) appropriated the late Ming and early Qing revival of interest in ancient This article is dedicated to Nathan Sivin for his contributions to the History of Science and Medicine in China. Unfortunately, I was unable to present it at the Johns Hopkins University sessions in July 2008 honoring Professor Sivin or include it in the forthcoming Asia Major festschrift in his honor. -

Chaste Lady Tan Or the Meaning Of

University of Warwick institutional repository This paper is made available online in accordance with publisher policies. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item and our policy information available from the repository home page for further information. To see the final version of this paper please visit the publisher’s website. Access to the published version may require a subscription. Authors: Anne Gerritsen Article Title: The Tale of Lady Tan Negotiating Place between Central and Local in Song-Yuan-Ming China Year of publication: 2008 Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/097194580801100201 Publisher statement: None The Marvelous Tale of Lady Tan: Between Central and Local in Song- Yuan-Ming China Introduction In 1368, when Zhu Yuanzhang 朱元璋 founded the Ming dynasty and became the first Ming emperor, he initiated a number of policies intended to strengthen central polity and weaken local variance (Dreyer 1982; Farmer 1995). County magistrates everywhere embarked on the building of local institutions such as temples and schools that mirrored those at the capital (Schneewind 2006). This process, which I refer to as ‘centralisation’, continued under the fifteenth-century successors of the Ming founder, until it slowly began to give way to a different process: the crumbling of central institutions and the growth of local and regional initiatives that we associate with the cultural flourishing of the late Ming (Mote 1999, 743–775). As Peter Bol has argued, centralisation, followed by a shift towards local initiatives and activism (‘localisation’), is a cyclical pattern in Chinese history, visible in, for example, the centralizing tendencies of the Northern Song followed by the localisation of the Southern Song, or the early Qing establishment of Manchu rule followed by the gradual waning of state control over society that characterises the nineteenth century (Bol 2003, 4). -

The Zhou Dynasty Around 1046 BC, King Wu, the Leader of the Zhou

The Zhou Dynasty Around 1046 BC, King Wu, the leader of the Zhou (Chou), a subject people living in the west of the Chinese kingdom, overthrew the last king of the Shang Dynasty. King Wu died shortly after this victory, but his family, the Ji, would rule China for the next few centuries. Their dynasty is known as the Zhou Dynasty. The Mandate of Heaven After overthrowing the Shang Dynasty, the Zhou propagated a new concept known as the Mandate of Heaven. The Mandate of Heaven became the ideological basis of Zhou rule, and an important part of Chinese political philosophy for many centuries. The Mandate of Heaven explained why the Zhou kings had authority to rule China and why they were justified in deposing the Shang dynasty. The Mandate held that there could only be one legitimate ruler of China at one time, and that such a king reigned with the approval of heaven. A king could, however, loose the approval of heaven, which would result in that king being overthrown. Since the Shang kings had become immoral—because of their excessive drinking, luxuriant living, and cruelty— they had lost heaven’s approval of their rule. Thus the Zhou rebellion, according to the idea, took place with the approval of heaven, because heaven had removed supreme power from the Shang and bestowed it upon the Zhou. Western Zhou After his death, King Wu was succeeded by his son Cheng, but power remained in the hands of a regent, the Duke of Zhou. The Duke of Zhou defeated rebellions and established the Zhou Dynasty firmly in power at their capital of Fenghao on the Wei River (near modern-day Xi’an) in western China. -

Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction Du Branch Patrimoine De I'edition

WU ZETIAN'S CONTRIBUTION TO THE CULTURAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE TANG DYNASTY By Rui Wang A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto © 2008 by Rui Wang Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-44981-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-44981-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

A Guide to the Use of Chinese Gazetteers* for Amdo Gray Tuttle

A Guide to the Use of Chinese Gazetteers* for Amdo Gray Tuttle 1. Research Tools I. Maps II. Reference Works for the Use and Locating of Gazetteers 2. Sources I. China-General II. Western Regions-General III. Amdo (provincial and sub-provincial gazetteers listed separately) A. Qinghai (Republic, PRC) B. Gansu (Ming, Qing, Republic, PRC) C. Sichuan (Qing, Republic, PRC) IV. Khams (Qing, Republic) V. Central Tibet (Qing, Republic) VI. Western Language Regional Accounts (Qing, Republic, PRC) 3. Secondary Studies I. Chinese language A. Journals B. Articles and Books II. Western language Note on bibliographic format. Title (bold indicates essential for reference) is given first with orginal date of publication in brackets in the case of most reprints (If I have not translated the title, see below for general contents). This is followed by author (last name first), year of publication, series in which the work is found, if applicable. The first asterisk (*) marks my notes on particular sources, mostly including page numbers, with important sections in bold for emphasis. When there are limited or no notes, I probably did not view the work but located the reference. The second asterisk (*) indicates where a particular work is held at Harvard if applicable. Entries with no such information are generally drawn from either Tibet outside the TAR or from my own library and that of Sue Costello (owner of a fairly complete collection of modern gazetteers and maps for Qinghai Amdo).** Note on the translation of Chinese administrative divisions: Sheng is always translated as province. Fu is translated as prefecture for the Ming and Qing periods. -

Proceedings of the Gemmological Association of Great Britain and Notices

The Journal of Gemmology2011 / Volume 32 / Nos. 5/8 Trapiche tourmaline The Gemmological Association of Great Britain The Journal of Gemmology / 2011 / Volume 32 / No. 5–8 The Gemmological Association of Great Britain 27 Greville Street, London EC1N 8TN, UK T: +44 (0)20 7404 3334 F: +44 (0)20 7404 8843 E: [email protected] W: www.gem-a.com Registered Charity No. 1109555 Registered office: Palladium House, 1–4 Argyll Street, London W1F 7LD President: Prof. A. H. Rankin Vice-Presidents: N. W. Deeks, R. A. Howie, E. A. Jobbins, M. J. O'Donoghue Honorary Fellows: R. A. Howie Honorary Life Members: H. Bank, D. J. Callaghan, T. M. J. Davidson, J. S. Harris, J. A. W. Hodgkinson, E. A. Jobbins, J. I. Koivula, M. J. O’Donoghue, C. M. Ou Yang, E. Stern, I. Thomson, V. P. Watson, C. H. Winter Chief Executive Officer: J. M. Ogden Council: J. Riley – Chairman, S. Collins, B. Jackson, S. Jordan, C. J. E. Oldershaw, L. Palmer, R. M. Slater Members’ Audit Committee: A. J. Allnutt, P. Dwyer-Hickey, E. Gleave, J. Greatwood, G. M. Green, K. Gregory, J. Kalischer Branch Chairmen: Midlands – P. Phillips, North East – M. Houghton, North West – J. Riley, South East – V. Wetten, South West – R. M. Slater The Journal of Gemmology Editor: Dr R. R. Harding Deputy Editor: E. A. Skalwold Assistant Editor: M. J. O’Donoghue Associate Editors: Dr A. J. Allnutt (Chislehurst), Dr C. E. S. Arps (Leiden), G. Bosshart (Horgen), Prof. A. T. Collins (London), J. Finlayson (Stoke on Trent), Dr J.