PDF of Entire Volume (110Pp, 3MB)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nominum Et Rerum

Index Nominum et Rerum Achilles Tatius Anne Dacier 200–2 Leucippe and Clitophon 19 Henry Fielding 109–28 passim adaptation 45, 46n, 49, 50–7, 60–2 Henry Fielding and William Young Chi-Raq 154n 113–4, 117 Ecclesiazusae Like a Fairytale 67, 81–5 Samuel Foote 121–2, 125–6 The Julie Thesmo Show 49–50, 56 Stephen Halliwell 148, 150 Lisa’s Sex Strike 60 Basil Kennett 114–5 Lysistrata Jones 154n, 338, 345 Gilbert Murray 284–306 passim Reform: A Farce 126 Benjamin Bickley Rogers 225 Panathenaia 244, 261–2 Earl of Shaftesbury 122 Shut Out 154n Samuel Parker 209 The Stories of Grandfather Jean Racine 199–200n Aristophanes 67–8, 70–80, 85, 87 The Works of Plato Abridg’d 122 addiction 129, 131, 134, 135, 140, 142, 145 sons Aelian 113, 209n Araros 3, 5–6 Aeschylus 5–7, 21, 28, 35–6, 71n, 86, 98–9, Philippos 5–6, 8n 100, 101, 170, 226n, 243, 255, 257, 258, surviving plays 261, 296n, 300, 318, 325 Acharnians 5, 19n, 27n, 28, 33, 34n, alcohol 31, 57, 117, 142, 145, 153, 159, 185, 194, 35, 38–9, 42n, 56, 59, 60n, 71, 73, 79, 246, 252, 295–6, 299, 302, 303n, 313, 345 91, 135n, 149n, 153, 156, 157, 158n, animal studies 129–30 160, 163, 166n, 167, 168, 170, 211n, 272, humanimal 129–147 passim 287, 288, 295, 296, 299, 301, 303, 308, prosthesis 129–31, 133 318, 369 Anninos, B. 241, 242n Birds 10n, 16, 38, 68, 71, 72–3, 79, 86–7, anthropological theory 42 92, 130, 133–4, 139n, 165, 175, 179, Antipater of Thessalonica 11 180n, 181–6 passim, 213n, 218, 219, Antonius Diogenes 220n, 226, 247, 264, 266–7, 269–82 Wonders Beyond Thule 18–9 passim, 286, 288, 293, 294, -

Beautiful Family! Broadway/ First National Tour: Beautiful; Betty/ Ensemble

SARAH BOCKEL (Carole King) is thrilled to be back on the road with her Beautiful family! Broadway/ First National Tour: Beautiful; Betty/ Ensemble. Regional: Million Dollar Quartet (Chicago); u/s Dyanne. Rocky Mountain Repertory Theatre- Les Mis; Madame Thenardier. Shrek; Dragon. Select Chicago credits: Bohemian Theatre Ensemble; Parade, Lucille (Non-eq Jeff nomination) The Hypocrites; Into the Woods, Cinderella/ Rapunzel. Haven Theatre; The Wedding Singer, Holly. Paramount Theatre; Fiddler on the Roof, ensemble. Illinois Wesleyan University SoTA Alum. Proudly represented by Stewart Talent Chicago. Many thanks to the Beautiful creative team and her superhero agents Jim and Sam. As always, for Mom and Dad. ANDREW BREWER (Gerry Goffin) Broadway/Tour: Beautiful (Swing/Ensemble u/s Gerry/Don) Off-Broadway: Sex Tips for Straight Women from a Gay Man, Cougar the Musical, Nymph Errant. Love to my amazing family, The Mine, the entire Beautiful team! SARAH GOEKE (Cynthia Weil) is elated to be joining the touring cast of Beautiful - The Carole King Musical. Originally from Cape Girardeau, Missouri, she has a BM in vocal performance from the UMKC Conservatory and an MFA in Acting from Michigan State University. Favorite roles include, Sally in Cabaret, Judy/Ginger in Ruthless! the Musical, and Svetlana in Chess. Special thanks to her vital and inspiring family, friends, and soon-to-be husband who make her life Beautiful. www.sarahgoeke.com JACOB HEIMER (Barry Mann) Theater: Soul Doctor (Off Broadway), Milk and Honey (York/MUFTI), Twelfth Night (Elm Shakespeare), Seminar (W.H.A.T.), Paloma (Kitchen Theatre), Next to Normal (Music Theatre CT), and a reading of THE VISITOR (Daniel Sullivan/The Public). -

Lysistrata Jones (Libretto)

0 “LYSISTRATA JONES” a musical comedy Book by Douglas Carter Beane Music and Lyrics by Lewis Flinn “Let each man exercise the life he knows” -- Aristophanes April 5, 2011 Protected by copyright 3 ACT ONE OPENING (From the darkness we see an ancient Grecian Symposia. Columns in smoke.) VOICES LA LA LA LA LA LA LA LA LA LA LA LA LA LA LA LA (the cast enters in hooded robes. HETAIRA, a provocateur and narrator, enters in full ancient Grecian attire. She’ll don several personas this evening, but right now she is herself. A courtesan, a storyteller, a guide, a tax payer) HETAIRAI Oh, citizens of Athens. ALL We are here, Hetairai. HETAIRAI Oh, Lysistrata. LYSISTRATA I am here, my sister, Hetairai. HETAIRAI What can a woman give but love love love? LYSISTRATA & GIRLS Oh, ye gods. Love love love. HETAIRAI And what do men do but fight fight fight. MEN Fight fight fight. Fight!! Fight!! Fight!! (Lights up full. The cast are in college attire, HETAIRAI remains in her Grecian attire. ALL Fight!! Fight!! Fight!! HETAIRA (Greek choral chanting) Citizens of Athens U., Townies and Alumni, too! Press Script 6/2/11 4 ALL You go Girl, Yeah Yeah!! You go Girl, Yeah Yeah!! HETAIRA Bare witness on this story that unfolds in front for you!! ALL You know, girl!! Yeah, yeah! You know, girl! Yeah, yeah! HETAIRA It’s sex and love and even sport! Now the two hours’ traffic of our court! ALL It’s a show, girl!! Yeah, yeah! A show, girl! Yeah, yeah! (singing) IT’S A LITTLE LIKE HETAIRA (singing) SOME PLAY BY ARISTOPHANES ALL IT’S A LITTLE LIKE HETAIRA HE’S DEAD, SO WE DO WHAT WE PLEASE ALL IT’S A LITTLE LIKE HETAIRA SOMETHING THAT’S OLD AND SO ARCANE ALL IT’S A LITTLE LIKE HETAIRA SO SUE US, ALL IT’S PUBLIC DOMAIN ALL RIGHT NOW! HETAIRA RIGHT HERE IN FRONT OF YOU ALL RIGHT NOW! HETAIRA WE GOT SOME BUSINESS TO DO Press Script 6/2/11 5 ALL RIGHT NOW! HETAIRA WE’RE GONNA FREE YOUR MIND ALL RIGHT NOW! HETAIRA JUST LEAVE YOUR CELL PHONES BEHIND HETAIRA The setting: Athens University. -

LIVE from LINCOLN CENTER "The Nance" TCA Bios

“The Nance” TCA Panelist Biographies Douglas Carter Beane’s credits on Broadway include Rodgers + Hammerstein’s Cinderella (Tony Award nomination), The Nance (nominated for five Tony Awards and two Drama Desk Awards), Lysistrata Jones (Tony Award nomination), Sister Act (Tony Award nomination), the stage adaptation of the film Xanadu (Outer Critics Circle & HX Awards for Best Musical, Drama Desk Award for Best Book, and four Tony nominations including Best Musical) and The Little Dog Laughed (Tony Award; West End Olivier Award nomination). His other plays include As Bees In Honey Drown (Outer Critics Circle John Gassner Award), Mr. and Mrs. Fitch, Music From a Sparkling Planet, The Country Club, Advice From a Caterpiller, The Cartells, and Mondo Drama. He has written the libretto for the Metropolitan Opera's Die Fledermaus, which is currently in their repertory, and his ballet, Artists and Models, 1929 is a part of the dance show In Your Arms. He wrote the film adaptation of his play Advice From a Caterpiller as well as the screenplay of To Wong Foo, Thanks For Everything, Julie Newmar. His play The Cartells has been optioned by HBO to be turned into a series. Lincoln Center Theater will produce his next play, Shows For Days, this spring and he is developing a play in verse, Fairycakes, which he will both write and direct. He resides in New York City with his husband, composer Lewis Flinn, their son, Cooper and daughter, Gabrielle. Nathan Lane most recently played Hickey in the acclaimed Robert Falls production of The Iceman Cometh in Chicago. His credits at Lincoln Center Theater include The Nance, Some Americans Abroad and The Frogs. -

Greek Drama Resources

Greek Drama Resources A Bibliography & Filmography Compiled by Dennis Lee Delaney Head, Professional Director Training Program Ohio University Theater Division, School of Dance, Film, and Theater © 2016 Websites / Internet Resources Ancient Greek Theater Resources Actors of Dionysus (www.actorsofdionysus.com) AOD has earned a reputation for making Greek tragedy seriously sexy (The Guardian) and since 1993 have built up an extensive track record of gripping and wholly accessible productions. Their website chronicles their production history, education publications/workshops, and also has a shop which features scripts, CDs and DVDs. Ancient Greek Drama (www.cbel.com/ancient_greek_drama) This is a useful compendium of 125 manually selected sites on various topics related to Greek drama, including individual articles on the playwrights and their works. Ancient Greek Theater (www.academic.reed.edu/humanities/ 110Tech.html) A page designed to provide an introduction to Ancient Greek Theater and provide tools for further research. Contains timelines, staging issues, bibliography and links. The Ancient Theatre Archive (www.whitman.edu/theatre/ theatretour/home.htm) A virtual reality tour of Greek and Roman Theatre architecture throughout the world, including mainland Europe, North Africa and the United Kingdom. The Archive of Performances of Greek and Roman Drama / University of Oxford (www.apgrd.ox.ac.uk) A comprehensive production history of ancient Greek and Roman drama in modern performance. It contains a database of information on more than -

Beautiful — the Carole King Musical Friday, January 24, 2020; 7:30 Pm; Saturday, January 25, 2020; 2 & 7:30 Pm; Sunday, January 26, 2020; 1 & 6:30 Pm

Beautiful — The Carole King Musical Friday, January 24, 2020; 7:30 pm; Saturday, January 25, 2020; 2 & 7:30 pm; Sunday, January 26, 2020; 1 & 6:30 pm Paul Blake Sony/ATV Music Publishing Jeffrey A. Sine Richard A. Smith Mike Bosner Harriet N. Leve/Elaine Krauss Terry Schnuck Orin Wolf Patty Baker/Good Productions Roger Faxon Larry Magid Kit Seidel Lawrence S. Toppall Fakston Productions/Mary Solomon William Court Cohen BarLor Productions Matthew C. Blank Tim Hogue Joel Hyatt Marianne Mills Michael J. Moritz, Jr. StylesFour Productions Brunish & Trinchero AND Jeremiah J. Harris PRESENT BOOK BY Douglas McGrath WORDS AND MUSIC BY Gerry Goffin & Carole King Barry Mann & Cynthia Weil MUSIC BY ARRANGEMENT WITH Sony/ATV Music Publishing STARRING Kennedy Caughell James D. Gish Kathryn Boswell James Michael Lambert Matt Loehr Rachel Coloff Matthew Amira Isaiah Bailey Edwin Bates Danielle Bowen Antoinette Comer Rosharra Francis Kevin Hack Torrey Linder Nick Moulton Kimberly Dawn Neumann Eliza Palasz Ben Toomer Nazarria Workman Hailee Kaleem Wright SCENIC DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN SOUND DESIGN Derek McLane Alejo Vietti Peter Kaczorowski Brian Ronan CASTING BY WIG & HAIR DESIGN MAKE-UP DESIGN ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR ASSOCIATE CHOREOGRAPHER Stephen Kopel, CSA Charles G. LaPointe Joe Dulude II David Ruttura Joyce Chittick ORCHESTRATIONS, VOCAL AND MUSIC ARRANGEMENTS MUSIC SUPERVISION AND ADDITIONAL MUSIC ARRANGEMENTS Steve Sidwell Jason Howland PRODUCTION STAGE MANAGER PRODUCTION MANAGEMENT MUSIC DIRECTOR MUSIC COORDINATOR Joel Rosen Juniper Street Productions, Inc. Alan J. Plado John Miller EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS TOUR BOOKING, ENGAGEMENT GENERAL MANAGER Sherry Kondor MANAGEMENT, PRESS & MARKETING Charlotte Wilcox Company Christine Russell Broadway Booking Office NYC CHOREOGRAPHED BY Josh Prince DIRECTED BY Marc Bruni www.harriscenter.net 2019-2020 PROGRAM GUIDE 23 Beautiful — The Carole King Musical continued KENNEDY CAUGHELL JAMES D. -

The Big Time an Old Carter Farm Concert Reading of a New Musical Comedy

THE BIG TIME AN OLD CARTER FARM CONCERT READING OF A NEW MUSICAL COMEDY Book by Music and lyrics by Douglas Carter Beane Douglas J. Cohen Music direction by Directed by Fred Lassen Douglas Carter Beane Featuring Raymond Bokhour, Bradley Dean, Santino Fontana, Debbie Gravitte, Jackie Hoffman, Michael McCormick, Laura Osnes, Will Swenson and musicians of the Princeton Symphony Orchestra Stage Manager Jen Wiener FRIDAY, JANUARY 31, 2020 8:00PM in the Matthews Theatre Assistive listening devices and large print program are available in the lobby. There will be a 15-minute intermission. No audio or video recording or photography permitted. DIRECTOR’S NOTE Douglas Carter Beane From his table at: Sardi’s, Broadway, USA Hello Theater Pals, Welcome to my subconscious––I sure Mr. C. has a way of getting into char- hope you got an aisle seat. How you are acter and telling a story but still making it about to experience this evening is one of all swing and having you feel like you’re my favorite ways to see a musical. A con- riding in a Cadillac convertible. You’ll fall cert—no sets, costumes, choreography, in love tonight. or fancy staging. Just material and talent. So, our show about a wacky terrorist Wow. I even formed a little company, was primed to open and the unthink- “Old Carter Farm,” to do these concerts, able happened: September 11th. The I love them so much. The name, you’ll show was put on hold. Whenever we’d forgive, came from my grandparents’ get ready to do the show again, another turkey farm. -

A-Christmas-Story-The-Musical.Pdf

® PHILADELPHIA, PENNSYLVANIA PLAYBILL.COM Dear Theatregoer, Welcome to an exciting holiday season at the Walnut! The level of activity in this theatre always amazes me during the most wonderful time of the year. The successes we have celebrated RYHU WKH SDVW \HDUV DV D QRWIRUSURÀW SURGXFLQJ WKHDWUH company would not be possible without the support of loyal theatregoers like you. We would like to say thank you. You help to make the Walnut the most popular theatre company in Philadelphia, and the most subscribed theatre company in the world! For me, the holidays are always a warm reminder of the importance of traditions honored with family and friends. In my home, as in many of your homes, watching A Christmas Story is part of our annual holiday celebration. The charming story of a child with a Christmas dream is one that many of us can relate to. Tonight on our stage, you’ll see many of our Walnut family who have come home for the holidays, as well as faces of new friends. I’m thrilled to share this hilarious, heart-warming Photo: Mark Garvin musical with you. Upstairs in our Independence Studio on 3, we have the triumphant story of Karola Siegel, Becoming Dr. Ruth 7KLVLVWKHIDVFLQDWLQJOLIHVWRU\RIDZRPDQZKRÁHGIURPWKH1D]LVLQ.LQGHUWUDQVSRUW joined the Haganah in Jerusalem as a scout and sniper, then traveled to the States and became America’s most famous sex therapist. Our intimate space is the perfect setting for this gripping tale. You don’t want to miss it. We are proud that our WST for Kids’ production of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol remains DPXVWVHH3KLODGHOSKLDKROLGD\WUDGLWLRQ(EHQH]HU6FURRJHDQG7LQ\7LPZLOOÀOOWKHKHDUWVRI audiences with joy on this very stage. -

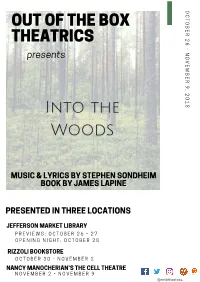

Into the Woods Program

O C T OUT OF THE BOX O B E R THEATRICS 2 6 - N presents O V E M B E R 9 , 2 0 1 8 MUSIC & LYRICS BY STEPHEN SONDHEIM BOOK BY JAMES LAPINE PRESENTED IN THREE LOCATIONS JEFFERSON MARKET LIBRARY P R E V I E W S : O C T O B E R 2 6 - 2 7 O P E N I N G N I G H T : O C T O B E R 2 8 RIZZOLI BOOKSTORE O C T O B E R 3 0 - N O V E M B E R 1 NANCY MANOCHERIAN’S THE CELL THEATRE N O V E M B E R 2 - N O V E M B E R 9 @ootbtheatrics CAST Amara J. Brady Gabriella Garcia Alie B. Gorrie* Alicia Krakauer* Alaina Mills* Celena Vera Morgan Sydney Ronis Brian Charles Katherine Yacko* Rooney* * Actors' Equity Association MUSICAL NUMBERS ACT I Prologue: "Into the Woods" "Hello, Little Girl" "I Guess This is Goodbye" "Maybe They're Magic" "I Know Things Now" "A Very Nice Prince" "Giants in the Sky" "Agony" "It Takes Two" "Stay With Me" "On the Steps of the Palace" "Ever After" ACT II Prologue: "So Happy" "Agony" "Lament" "Any Moment' "Moments in the Woods" "Your Fault" "Last Midnight" "No More" "No One is Alone" Finale: "Children Will Listen" MUSICIANS Piano.....................................................................................................Anessa Marie Into the Woods will be performed with an intermission. Run Time: 2 hours 40 minutes Opening Night: October 28, 2018 nancy manocherian’s Jefferson Market Library RIzzoli Bookstore the cell theatre 425 Avenue of the Americas 1133 Broadway 338 W. -

The Madison Square Garden Company Announces the Creative Team for New York Spectacular Starring the Radio City Rockettes, Presented by Chase

March 10, 2016 The Madison Square Garden Company Announces the Creative Team for New York Spectacular Starring The Radio City Rockettes, Presented by Chase Emmy Award-Winner Mia Michaels as Director and Choreographer, Drama Desk Award-Winner Douglas Carter Beane as Show Writer, and More New York Spectacular Starring The Radio City Rockettes Will Run June 15 - August 7 at Radio City Music Hall NEW YORK, March 10, 2016 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- The Madison Square Garden Company (NYSE:MSG) announced today that three-time Emmy Award-winner Mia Michaels will serve as director and choreographer of the New York Spectacular Starring The Radio City Rockettes, presented by Chase. Michaels will be joined by Drama Desk Award-winner Douglas Carter Beane as the show's writer, Alain Lortie as lighting designer, and multi-media and entertainment studio, Moment Factory, as video designer. Returning from 2015's successful inaugural production of the then called New York Spring Spectacular are set designer Patrick Fahey and costume designer Emilio Sosa, and from the Radio City Christmas Spectacular, sound designer Steve Canyon Kennedy. New York Spectacular Starring The Radio City Rockettes celebrates New York City in the summertime centered around the trip of a lifetime for two kids, who, while on a vacation in New York, are separated from their parents. The city magically comes to life to show them its many splendid wonders and helps to reunite their family in the end. The production will run at Radio City Music Hall from June 15-August 7, 2016. Tickets are currently available via Rockettes.com/newyork and at the Radio City box office. -

Patti Murin, Josh Segarra and the Cast of Lysistrata Jones

BATTLE OF THE SEXES: (left to right) Patti Murin, Josh Segarra and the cast of Lysistrata Jones. Photo: Joan Marcus Theater Review Lysistrata Jones one of best musicals of 2011 LYSISTRATA JONES Book by Douglas Carter Beane Music & lyrics by Lewis Flinn Directed & choreographed by Dan Knechtges Walter Kerr Theatre 219 West 48th Street (212-239-6200), www.LysistrataJones.com By David NouNou It is no secret that the musicals that were offered this fall/winter season were from hunger. With the exception of a brilliant revival of Follies, which is unfortunately closing way too soon, the pickings have been mighty slim. From the abysmal revival of Godspell to the disastrous Bonnie & Clyde, there has been nothing as fresh, delightful and entertaining as Lysistrata Jones. Finally, a musical that can be enjoyed for the holiday season and beyond has arrived just in time. Based on Aristophanes’ Lysistrata, Douglas Carter Beane has updated the storyline and set it in a modern-day gymnasium where the Athens men’s basketful team has lost every game for over 30 years. Lysistrata Jones comes to the university and takes it upon herself to create a cheerleading squad to urge the boys on to victory. Upon losing the game, that is when Lyssie and the girls decide to withhold sex from the players until they will finally win a game. Thus begins the complication and the fun. Playwright Mr. Beane has written a delicious book for this musical, full of wit and genuine humor. (We at StageZine.com never reveal any of the funny quotes in a review because we feel it is a spoiler alert, and they are best enjoyed when hearing them fresh within the context of the show.). -

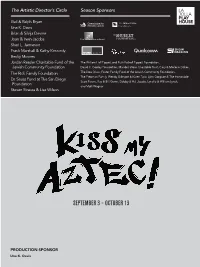

To Read the Program Online

The Artistic Director’s Circle Season Sponsors Gail & Ralph Bryan Una K. Davis Brian & Silvija Devine Joan & Irwin Jacobs Sheri L. Jamieson Frank Marshall & Kathy Kennedy Becky Moores Jordan Ressler Charitable Fund of the The William Hall Tippett and Ruth Rathell Tippett Foundation, Jewish Community Foundation David C. Copley Foundation, Mandell Weiss Charitable Trust, Gary & Marlene Cohen, The Rich Family Foundation The Dow Divas, Foster Family Fund of the Jewish Community Foundation, The Fredman Family, Wendy Gillespie & Karen Tanz, Lynn Gorguze & The Honorable Dr. Seuss Fund at The San Diego Scott Peters, Kay & Bill Gurtin, Debby & Hal Jacobs, Lynelle & William Lynch, Foundation and Molli Wagner Steven Strauss & Lise Wilson SEPTEMBER 3 – OCTOBER 13 PRODUCTION SPONSOR Una K. Davis Dear Friends, LA JOLLA PLAYHOUSE PRESENTS Christopher Ashley Debby Buchholz There’s a moment in tonight’s musical The Rich Family Artistic Director of La Jolla Playhouse Managing Director of La Jolla Playhouse – don’t worry, no spoilers here – where IN ASSOCIATION WITH a power-mad viceroy, overseeing BERKELEY REPERTORY THEATRE Spain’s colonization of the Americas, MISSION STATEMENT: envisions a glorious future in which most of the towns along the western La Jolla Playhouse advances coast of North America will eventually theatre as an art form and as a vital be named after Catholic saints. San Diego, regardless of the social, moral and political platform thoughts or opinions of our area’s Native population at the by providing unfettered creative time, would indeed become one of those towns; the Spanish opportunities for the leading artists explorer Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo christened it San Miguel in BOOK BY of today and tomorrow.