The Just War Tradition and the World After September 11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

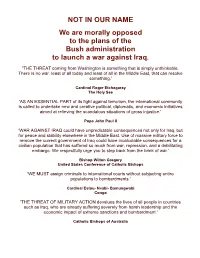

NOT in OUR NAME We Are Morally Opposed to the Plans of the Bush Administration to Launch a War Against Iraq

NOT IN OUR NAME We are morally opposed to the plans of the Bush administration to launch a war against Iraq. 'THE THREAT coming from Washington is something that is simply unthinkable. There is no war, least of all today and least of all in the Middle East, that can resolve something.' Cardinal Roger Etchegaray The Holy See 'AS AN ESSENTIAL PART of its fight against terrorism, the international community is called to undertake new and creative political, diplomatic, and economic initiatives aimed at relieving the scandalous situations of gross injustice.' Pope John Paul II 'WAR AGAINST IRAQ could have unpredictable consequences not only for Iraq, but for peace and stability elsewhere in the Middle East. Use of massive military force to remove the current government of Iraq could have incalculable consequences for a civilian population that has suffered so much from war, repression, and a debilitating embargo. We respectfully urge you to step back from the brink of war.' Bishop Wilton Gregory United States Conference of Catholic Bishops 'WE MUST assign criminals to international courts without subjecting entire populations to bombardments.' Cardinal Estou- Nvabi- Bamungwabi Congo 'THE THREAT OF MILITARY ACTION devalues the lives of all people in countries such as Iraq, who are already suffering severely from harsh leadership and the economic impact of extreme sanctions and bombardment.' Catholic Bishops of Australia No war in our name. The Benedictine Monks of Weston Priory Fall/Winter 2002 Bulletin The Monks of Weston Priory 58 Priory Hill Road, Weston, VT 05161-6400 Tel: 802-824-5409; Fax: 802-824-3573 . -

CNZP Streamlined JMT Reductions.Docx

Journal of Moral Theology, Vol. 5, No. 1 (2016): 111-128 “For He is our Peace” Thomas Aquinas on Christ as Cause of Peace in the City of Saints Matthew A. Tapie OST SCHOLARS WHO HAVE COMMENTED upon Aquinas’s view of peace have done so in the context of discussing his teaching that peace, defined as the “tranquility of or- M der” (tranquillitas ordinis), is the aim of a just war.1 Alt- hough “civic peace” falls short of the perfect peace that the saints will 1 An abridged version of this essay appears in Reading Scripture as a Political Act copyright © 2015 Fortress Press. In Summa Theologiae II-II 29.2, Aquinas adopts Augustine’s definition of peace as tranquillitas ordinis. English translations of the Summa Theologiae are from the Benziger edition unless otherwise noted. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, trans. Fathers of the English Dominican Province (New York: Benziger, 1948). Avery Cardinal Dulles observes that, “political theorists have frequently dealt with …civic peace …according to Saint Thomas.” Avery Cardinal Dulles, A Church to Believe In: Discipleship and the Dynamics of Freedom (New York, NY: Crossroads Publishing, 1983), 149. Most scholarly comment upon Aqui- nas’s view of peace treats the concept in the context of his teaching on war in ST II-II q. 40. John Finnis’s treatment of peace is representative since he places emphasis on the fact that Aquinas taught that genuine peace is not the absence of war but the maintenance of the common good. John Finnis, “The Ethics of War and Peace in the Catholic Natural Law Tradition,” in Christian Political Ethics, The Ethikon Series in Comparative Ethics (Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 2008), 193. -

Liturgy 40 Years After the Council the Oneness of the Church

Aug. 27–Sept.America 3, 2007 THE NATIONAL CATHOLIC WEEKLY $2.75 The Oneness of Liturgy 40 the Church Years After Richard the Council Gaillardetz Godfried Danneels Richard A. Blake on Ingmar Bergman as a religious thinker Willard F. Jabusch on Franz Jägerstätter NE SUMMER in Maryland I vol- would offer, to craft and enforce laws that unteered to teach in a local further the common good of all Ameri- America Head Start program, but what I cans. Humphrey fit the bill. What I Published by Jesuits of the United States needed instead was a paying didn’t expect was to be inspired by co- Ojob. So when my roommate dashed home workers. Editor in Chief with the news that the Democratic Yet I saw about me men and women Drew Christiansen, S.J. National Committee was hiring over at of varying ages, types and career levels the Watergate building, we rushed back who embodied another democratic ideal: Managing Editor to the District to apply and interview. the politically active citizen as party Robert C. Collins, S.J. That night we landed jobs in the press worker. These people toiled behind the office. It was 1968, a few months before scenes and within the system. Their hard Business Manager Election Day. And the Hubert Humphrey work, enthusiasm and dedication moved Lisa Pope versus Richard Nixon presidential race me; all of us worked nearly around the was entering its final critical leg. clock as the weeks sped by. And while Editorial Director This is the story of how a college senior staff members were surely sus- Karen Sue Smith sophomore, too young to vote or drink, tained by the hope of the power, status managed to become inebriated from her and financial reward victory would bring, Online Editor first big whiff of party politics. -

UNCREDIBLE: Broke Out

SPRING 201620162016 ••• NUMBER 333 A JOURNALJOURNALJOURNAL OFOFOF CHRISTIANITYCHRISTIANITYCHRISTIANITY &&& AMERICANAMERICANAMERICAN FOREIGNFOREIGNFOREIGN POLICYPOLICYPOLICY THE MORALMORAL UNDERPINNINGSUNDERPINNINGS OFOF JUSTJUST RETRIBUTION:RETRIBUTION: JUSTICE && CHARITYCHARITY ININ SYMBIOSISSYMBIOSIS BY JJ DDARYL CCHARLES MORAL MULTILATERALISM:MULTILATERALISM: SPONSORED BYBYBY THE OBAMAOBAMA DOCTRINE’SDOCTRINE’S CHRISTIANCHRISTIAN REALISMREALISM BY MMATT NN GGOBUSH SPRING SPRING SPRING UNCREDIBLE: OBAMA && THETHE ENDEND OFOF AMERICANAMERICAN POWERPOWER 2016 2016 2016 BY MMARC LLIIVECCHE • • • ALSO:: MMARK TTOOLEY ON TTRUMP && THE INADEQUACYINADEQUACY OF “A“AMERICA FFIRSTIRST”” •• BBRIAN AAUTEN ON JUSTJUST NUMBER NUMBER NUMBER SURVEILLANCESURVEILLANCE •• FFREDERICK DDOUGLAS ON CHOOSING RIGHT FROM WRONG •• AANDREW T.T. WWALKER ON A BBAPTIST VIEW OF WOMEN ININ WAR •• AAUGUST LLANDMESSER FOLDS HIS ARMS •• AALAN DDOWD REFLECTS ON THE NATION STATESTATE && INTERNATIONALINTERNATIONAL ORDER •• SSUSANNAH BBLACK && THE CCALIPHATE •• GENERAL GGEORGE MMARSHALL’’SS VISION FOR AAMERICA •• GGIDEONIDEON SSTRAUSS ON POLITICAL HOPE FOR 3 3 3 AFRICA •• RROBERT NNICHOLSONICHOLSON ON IISLAMSLAM,, CCHRISTIANITY,, && THE END OF PPALESTINE Providence_spring16_final_cover_spine.inddProvidence_spring16_final_cover_spine.indd 111 5/31/165/31/16 8:368:368:36 AMAMAM It is worth touching on two men who had killed him to a and puts us instead on a foot- points. First, and surprisingly parley, and put to them the case ing for war. Hardheaded realism perhaps, Dayan -

March 7, 2003 Vol

Inside Archbishop Buechlein . 4, 5 Editorial . 4 Question Corner . 13 The Sunday and Daily Readings . 13 Serving the CChurchCriterion in Centralr andi Southert n Indianae Since 1960rion www.archindy.org March 7, 2003 Vol. XXXXII, No. 21 $1.00 Pope sends Cardinal Laghi to confer with Bush on Iraq VATICAN CITY (CNS)—Pope John ambassador to the United States and a long- White House spokesman Ari Fleischer Italian Cardinal Pio Paul II sent a personal envoy, Italian time friend of Bush’s father, former said no meeting with Cardinal Laghi was CNS photo Laghi is pictured in an Cardinal Pio Laghi, to Washington to confer President George H.W. Bush, was expected scheduled that day and he would keep undated file photo. with President George W. Bush and press to arrive in Washington on March 3 bearing reporters informed “as events warrant and Pope John Paul II for a peaceful solution to the Iraqi crisis. a papal message for the current president. as events come closer.” dispatched the cardinal The move, which had been under dis- In Washington, a spokeswoman for the Cardinal Laghi told the Italian newspa- to Washington to cussion at the Vatican for weeks, was the current papal nuncio, Archbishop Gabriel per Corriere della Sera, “I will insist, in confer with President pope’s latest effort to head off a war he Montalvo, said only the Vatican could the pope’s name, that all peaceful means George W. Bush and fears could cause a humanitarian crisis confirm Cardinal Laghi’s schedule in be fully explored. Certainly there must be press for a peaceful and provoke new global tensions. -

Rift on Immigration Widens for Conservatives and Cardinals

March 19, 2006 The Nation Rift on Immigration Widens for Conservatives and Cardinals By RACHEL L. SWARNS The New York Times WASHINGTON THE fierce battle over the future of America's immigration system is spilling from Capitol Hill onto the airwaves, as conservatives accuse Democrats, human rights groups and even some labor unions of trying to stymie Republican efforts to stem the tide of illegal immigration. But in recent weeks, some commentators and prominent Republicans have turned their swords against another formidable foe in their battle to tighten the borders: the Roman Catholic Church. Immigration has long caused friction between the church, with its advocacy for migrants, and conservatives, who want to slow illegal crossings over the Mexican border. But as Congress wrestles with the fate of the nation's 11 million illegal immigrants, that tension has escalated into a sharp war of words, highlighting the divide among some Republicans and Catholics who have fought side by side on other issues like abortion and same-sex marriage. In December, after the Republican-controlled House of Representatives passed a tough border security bill that, among other things, would make it a crime to assist illegal immigrants, the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops assailed it as extremely punitive and called on its flock to oppose it. Church officials have sent lobbyists to Congress and this month parishes sent members to rallies in Chicago and Washington to push for legislation that would legalize undocumented immigrants and put them on the path to citizenship. Some Republicans are firing back. In February, Representative Tom Tancredo, a Colorado Republican who opposes illegal immigration, took issue with Catholic bishops, among other religious leaders, "for invoking God when arguing for a blanket amnesty" for illegal immigrants. -

The Catholic Bishops and the Rise of Evangelical Catholics

religions Article The Catholic Bishops and the Rise of Evangelical Catholics Patricia Miller Received: 27 October 2015; Accepted: 22 December 2015; Published: 6 January 2016 Academic Editor: Timothy A. Byrnes Senior Correspondent, Religion Dispatches; [email protected]; Tel.: +1-703-519-8379 Abstract: White Catholics are increasingly trending toward the Republican Party, both as voters and candidates. Many of these Republican-leaning Catholics are displaying a more outspoken, culture-war oriented form of Catholicism that has been dubbed Evangelical Catholicism. Through their forceful disciplining of pro-choice Catholics and treatment of abortion in their quadrennial voting guides, as well as their emphasis on “religious liberty”, the U.S. bishops have played a major role in the rise of these Evangelical Catholics. Keywords: U.S. Catholic bishops; abortion; Republican; Democratic; voting 1. Introduction While the Catholic Church is associated with opposition to legalized abortion, a review of the historical record shows that the anti-abortion movement was largely fomented by the Catholic hierarchy and fueled by grassroots Evangelical opposition to abortion [1]. Lay Catholics have largely tracked general public opinion on abortion, with just over half of white Catholics saying it should be legal; polls have consistently found that only about 13% of Catholics support the position of the Catholic Church that abortion should be illegal in all circumstances [2,3]. As a result, Catholic voters have been comfortable supporting candidates who favor abortion rights, adding to their reputation as swing voters who have backed both successful Republican and Democratic presidential candidates. However, a substantial subset of white Catholic voters now appears more firmly committed to the Republican Party. -

Catholic Mediation in the Basque Peace Process: Questioning the Transnational Dimension

religions Article Catholic Mediation in the Basque Peace Process: Questioning the Transnational Dimension Xabier Itçaina 1,2 1 CNRS—Centre Emile Durkheim, Sciences Po Bordeaux, 11 allée Ausone, 33607 Pessac, France; [email protected] 2 GEZKI, University of the Basque Country, 20018 San Sebastian, Spain Received: 30 March 2020; Accepted: 17 April 2020; Published: 27 April 2020 Abstract: The Basque conflict was one of the last ethnonationalist violent struggles in Western Europe, until the self-dissolution in 2018 of ETA (Euskadi ta Askatasuna, Basque Country and Freedom). The role played by some sectors of the Roman Catholic Church in the mediation efforts leading to this positive outcome has long been underestimated, as has the internal pluralism of the Church in this regard. This article specifically examines the transnational dimension of this mediation, including its symbolic aspect. The call to involve the Catholic institution transnationally was not limited to the tangible outcomes of mediation. The mere fact of involving transnational religious and non-religious actors represented a symbolic gain for the parties in the conflict struggling to impose their definitions of peace. Transnational mediation conveyed in itself explicit or implicit comparisons with other ethnonationalist conflicts, a comparison that constituted political resources for or, conversely, unacceptable constraints upon the actors involved. Keywords: Basque conflict; nationalism; Catholic Church; Holy See; transnational mediation; conflict resolution 1. Introduction The Basque conflict was one of the last ethnonationalist violent struggles in Western Europe, until the definitive ceasefire (2011), decommissioning (2017), and self-dissolution (2018) of the armed organization ETA (Euskadi ta Askatasuna, Basque Country and Freedom). -

World Without War Council - Midwest Archives, 1961 - 2006

1 World Without War Council - Midwest Archives, 1961 - 2006 Box 1: A. Overview, 1961 - 2006; B. Challenges and Lessons Learned, 1991 - 2010 Box 2: Turn Toward Peace, Midwest Regional Office, 1961 - 1970: Ed Doty, Chicago Area Coordinator, and Jack Bollens, National Staff in Chicago Boxes 3 & Box 4: World Without War Council - Midwest, 1970 - 1977 (June): Lowell Livezey, Director Box 5: World Without War Council - Midwest, 1977 (July) - 1981: Karen Minnice and Robert Woito, Co-Directors Boxes 6 & 7: World Without War Council - Midwest, 1982 - 1995: Robert Woito, Dir. Boxes 8 & 9: World Without War Council - Midwest, 1996 - 2006: Robert Woito, Dir. Box 10: Interne/Fellows Program: 1961 - 2006 Box 11: Democracy & Peace: 1965 - 2006 Box 12: Bayard Rustin and Project South Africa, 1984 - 1991 Box 13: Strategies of Change: But What Can I Do? A. Citizen: Form A Citizen Peace Effort with Community Peace Centers, Peace Education in Churches and Responses to Crises, 1961 - 1971 B. NGO!s: Engage Voluntary Organizations in work for a World Without War 1965 -1990 C. Government: Improve American Competence in World Affairs, 1975 - 2006 Box 14: Strategies of Peace: A. Individual: Civilian defense, Gandhian Satyagraha, Conscience and War -- witness B. Society: global civil society, aiding transitions to democracy, extending the demo- cratic peace in time among democracies and geographically C. Government: American Peace Initiatives Strategy Box 15: Newsletters (Communique, American Purpose and Democratic Values) Boxes 16 & 17: World Without War Publications, 1967 - 2006 Box 18: Finances Box l.B. Conclusion: Challenges (2010) & Lessons Learned (1991 - 2010) 2 Box 1: A. Overview We live in a country distinguished from many others by its wealth, size, diversity, technological capability, and most of all, by the idea that formed it. -

CATHOLIC BISHOPS, PUBLIC POLICY and the 2004 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION by Gretchen M

CATHOLIC BISHOPS, PUBLIC POLICY AND THE 2004 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION By Gretchen M. MacMillan Copyright Gretchen M. MacMillan Preliminary draft; not for citation without permission Paper presented at the annual meetings of the Canadian Political Science Association, University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, June 2005 1 CATHOLIC BISHOPS, PUBLIC POLICY AND PRESIDENTIAL POLITICS IN THE UNITED STATES In the recent presidential election in the United States the role played by traditional Christian values gained a great deal of attention. This was primarily because of the link between the fundamentalist Christian right and the Republican Party. Another significant connection between Christian values and the election was the role played by the Bishops of the Roman Catholic Church. The major source of contention arose over the official Church position on abortion, same-sex marriage and stem-cell research and the position adopted by the Democratic presidential candidate John Kerry a Catholic whose position on these issues was at variance with those of his Church. The possible role they played in his defeat has major implications not only for Catholics in public life but also for the future of the Democratic Party. At the same time the relationship of Catholic social teachings and the role of the Bishops both in the formulation of public social policy and as moral leaders of the Catholic community are of importance for a group that makes up about one quarter of the American electorate. It is the purpose of this paper to examine some of these implications for the future role played by Catholics and the Catholic Church in American public policy. -

THE GLOBAL QUEST for TRANQUILLITAS ORDINIS Pacem in Terris , Fifty Years Later

The Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences XVIII Plenary Session THE GLOBAL QUEST FOR TRANQUILLITAS ORDINIS Pacem in Terris , Fifty Years Later 27 April-1 May 2012 • Casina Pio IV Introduction p . 3 Programme p. 5 List of Participants p. 10 Biographies of Participants p. 12 Memorandum p. 18 Holy Masses p. 19 SCIE IA NT EM IA D R A V C M A S S O O O A A I I I C C C C C C I I I I I I I I A A A A A A A F F F I I I I L L L L L L T T T T I I I I V V V N N N N M M O O O P P P VAtICAn CIty 2012 Peace is a gift which God entrusts to human responsibility, to be fo - stered through dialogue and respect for the rights of all, through re - conciliation and through forgiveness. In the prophecy of Zechariah, Jesus found not only the image of the king of peace arriving on a donkey, but also the vision of the slain shepherd, who saves by his death, as well as the image of the Pierced One on whom all eyes will gaze. As Prefect, Pilate represented Roman law, on which the Pax Romana rested – the peace of the empire that spanned the world. this peace was secured, on the one hand, through Rome’s military might. But mil - itary force alone does not generate peace. Peace depends on justice. (Benedict XVI, Angelus 28 March 2010; Jesus of Nazareth ; Vatican City 2011, pp. -

Conference Booklet

Ethics in Action for Sustainable and Integral Development Peace 2-3 February 2017 | Casina Pio IV | Vatican City Peacebuilding through active nonviolence is the natural and necessary complement to the Church’s continuing efforts to limit the use of force by the application of moral norms; she does so by her participation in the work of international “ institutions and through the competent contribution made by so many Christians to the drafting of legislation at all levels. Jesus himself offers a “manual” for this strategy of peacemaking in the Sermon on the Mount. The eight Beatitudes (cf. Mt 5:3-10) provide a portrait of the person we could describe as blessed, good and authentic. Blessed are the meek, Jesus tells us, the merciful and the peacemakers, those who are pure in heart, and those who hunger and thirst for justice. Nonviolence: a Style of Politics for Peace, Message of His Holiness Pope Francis for the Celebration of the Fiftieth World Day of Peace, 1 January” 2017 2 Ethics in Action for Sustainable and Integral Development | Peace The Importance of Peace he purpose of this meeting is to answer the other technological advances. And the socio-cultural question posed by Pope Benedict XVI to the landscape is being reshaped by an explosive growth in T representatives of the world’s religions gathered information and communications technology, and by in Assisi to pray for peace: “What is the state of peace the revolution in social norms and morals that define today?” Accordingly, Ethics in Action will reflect on how an individualistic society rooted in the technocratic to achieve the tranquillitas ordinis (the tranquility of paradigm, at the expense of notions such as virtue, the order), as Saint Augustine denoted peace (De Civitate common good, and social justice.