Wallace Williams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Your Virtual Visit - 63 to the Australian Army Museum of Western Australia

YOUR VIRTUAL VISIT - 63 TO THE AUSTRALIAN ARMY MUSEUM OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA Throughout 2021, the Virtual Visit series will be continuing to present interesting features from the collection and their background stories. The Australian Army Museum of Western Australia is now open four days per week, Wednesday through Friday plus Sunday. Current COVID19 protocols including contact tracing will apply. National Memories of the Somme Beaumont Hamel, Delville Wood, Helen’s Tower, Thiepval An earlier Virtual Visit (VV61) focussed on the Australian remembrance of the Somme battles of July – November 1916. Other countries within the British Empire suffered similar trauma as national casualties mounted. They too chose to commemorate their sacrifice through evocative national memorials on the Somme battlefield. Newfoundland Regiment - Beaumont Hamel During the First World War, Newfoundland was a largely rural Dominion of the British Empire with a population of 240,000 people, and not yet part of Canada. In August 1914, Newfoundland recruited a battalion for service with the British Army. In a situation reminiscent of the khaki shortage facing the first WA Contingent to the Boer War, recruits in the Regiment were nicknamed the "Blue Puttees" due to the unusual colour of the puttees, chosen to give the Newfoundland Regiment a unique look and due to the unavailability of woollen khakis on the island. On 20 September 1915, the Regiment landed at Suvla Bay on the Gallipoli peninsula. At that stage of the campaign, the Newfoundland Regiment faced snipers, artillery fire and severe cold, as well as the trench warfare hazards of cholera, dysentery, typhus, gangrene and trench foot. -

SUPPLEMENT to the LONDON GAZETTE, 31St DECEMBER 1960 8899

SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 31sT DECEMBER 1960 8899 John Richard PHEAZEY, Esq., Vice-Chairman and George' Douglas BAILEY, Esq., Assistant Account- Joint General Manager, Standard Telephones ant and Comptroller General, Board of Inland and Cables, Ltd. Revenue. Ralph Bonner PINK, Esq., V.R.D., J.P. For Louisa Priscilla, Alderman Mrs. BAILEY, J.P. For political and public services in Wessex. political and public services in Essex. Allan Richard PLOWMAN, Esq., Director of Con- Joseph Taylor Robertson BAIN, Esq., Deputy tracts, Ministry of Works. •Controller, Northern Region, Ministry of Alan RAWSTHORNE, Esq., Composer. Labour. Alderman Harry Howard ROBINSON, J.P. For Herbert William BAKER, Esq., Superintendent political and public services in Cheshire. Engineer, Television, London Studios, British Arthur Alexander RUBBRA, Esq., Technical Broadcasting Corporation. Director, Rolls-iRoyce, Ltd. Albert Harry Roy BALL, Esq., lately Principal, James Bryan SCOTT, Esq., D.F.C., Sales Director, Methodist College, Belfast. Crompton Parkinson, Ltd. Sidney BALLANCE, Esq., Chief Constable, Barrow- Ernest Julius Walter SIMON, Esq., Emeritus in-Furness Borough Police Force. Professor of Chinese, University of London. Herbert Richard BALMER, Esq., Assistant Chief Harvie Kennard SNELL, Esq., M.D., M.R.C.S., Constable, Liverpool City Police Force. Director of Medical Services, Prison Com- David Armitage BANNERMAN, Esq., M.B.E. mission. Ornithologist. William Ebenezer Clank SOUSTER, Esq., J.P. Malcolm BARNETT, Esq., M.B.E., Member, South For political and public services in Burton-on- West Region, National Savings Committee. Trent. John Denton Ashworth BARNICOT, Esq., Director, Gertrude Annie, Alderman Mrs. STEVENSON. For Books Department, British Council. political and public services in Leeds. -

Montage Fiches Rando

Leaflet Walks and hiking trails Haute-Somme and Poppy Country 8 Around the Thiepval Memorial (Autour du Mémorial de Thiepval) Peaceful today, this Time: 4 hours 30 corner of Picardy has become an essential Distance: 13.5 km stage in the Circuit of Route: challenging Remembrance. Leaving from: Car park of the Franco-British Interpretation Centre in Thiepval Thiepval, 41 km north- east of Amiens, 8 km north of Albert Abbeville Thiepval Albert Péronne Amiens n i z a Ham B . C Montdidier © 1 From the car park, head for the Bois d’Authuille. The carnage of 1st July 1916 church. At the crossroads, carry After the campsite, take the Over 58 000 victims in just straight on along the D151. path on your right and continue one day: such is the terrible Church of Saint-Martin with its as far as the village. Turn left toll of the confrontation war memorial built into its right- toward the D151. between the British 4th t Army and the German hand pillar. One of the many 3 Walk up the street opposite s 1st Army, fewer in number military pilgrimages to Poppy (Rue d’Ovillers) and keep going e r but deeply entrenched. Country, the emblematic flower as far as the crossroads. e Their machine guns mowed of the “Tommies”. By going left, you can cut t down the waves of infantrymen n At the cemetery, follow the lane back to Thiepval. i as they mounted attacks. to the left, ignoring adjacent Take the lane going right, go f Despite the disaster suffered paths, as far as the hamlet of through the Bois de la Haie and O by the British, the battle Saint-Pierre-Divion. -

Nigeria and the Death of Liberal England Palm Nuts and Prime Ministers, 1914-1916

Britain and the World Nigeria and the Death of Liberal England Palm Nuts and Prime Ministers, 1914-1916 PETER J. YEARWOOD Britain and the World Series Editors Martin Farr School of Historical Studies Newcastle University Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK Michelle D. Brock Department of History Washington and Lee University Lexington, VA, USA Eric G. E. Zuelow Department of History University of New England Biddeford, ME, USA Britain and the World is a series of books on ‘British world’ history. The editors invite book proposals from historians of all ranks on the ways in which Britain has interacted with other societies since the seventeenth century. The series is sponsored by the Britain and the World society. Britain and the World is made up of people from around the world who share a common interest in Britain, its history, and its impact on the wider world. The society serves to link the various intellectual commu- nities around the world that study Britain and its international infuence from the seventeenth century to the present. It explores the impact of Britain on the world through this book series, an annual conference, and the Britain and the World journal with Edinburgh University Press. Martin Farr ([email protected]) is the Chair of the British Scholar Society and General Editor for the Britain and the World book series. Michelle D. Brock ([email protected]) is Series Editor for titles focusing on the pre-1800 period and Eric G. E. Zuelow (ezuelow@une. edu) is Series Editor for titles covering the post-1800 period. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/14795 Peter J. -

Tanks at the Battle of Flers-Courcelette, September 1916

“A useful accessory to the infantry, but nothing more” Tanks at the Battle of Flers-Courcelette, September 1916 Andrew McEwen he Battle of Flers-Courcelette Fuller was similarly unkind about the Tstands out in the broader memory Abstract: The Battle of Flers- tanks’ initial performance. In his Tanks of the First World War due to one Courcelette is chiefly remembered in the Great War, Fuller wrote that the as the combat introduction of principal factor: the debut of the tanks. The prevailing historiography 15 September attack was “from the tank. The battle commenced on 15 maligns their performance as a point of view of tank operations, not September 1916 as a renewed attempt lacklustre debut of a weapon which a great success.”3 He, too, argued that by the general officer commanding held so much promise for offensive the silver lining in the tanks’ poor (GOC) the British Expeditionary warfare. However, unit war diaries showing at Flers-Courcelette was that and individual accounts of the battle Force (BEF) General Douglas Haig suggest that the tank assaults of 15 the battle served as a field test to hone to break through German lines on September 1916 were far from total tank tactics and design for future the Somme front. Flers-Courcelette failures. This paper thus re-examines deployment.4 One of the harshest shares many familiar attributes the role of tanks in the battle from verdicts on the tanks’ debut comes with other Great War engagements: the perspective of Canadian, British from the Canadian official history. and New Zealand infantry. It finds troops advancing across a shell- that, rather than disappointing Allied It commented that “on the whole… blasted landscape towards thick combatants, the tanks largely lived the armour in its initial action failed German defensive lines to capture up to their intended role of infantry to carry out the tasks assigned to it.” a few square kilometres of barren support. -

September 1916

SEPTEMBER 1916 TANKS TRY TO END STALEMATE September 1916 saw many persistent British attacks and enemy counterattacks around individual German strongholds (sometimes for the second or third time) - Delville Wood, Pozieres, Mouquet Farm, Guillemont, Ginchy, Morval, Thiepval and Flers-Courcelette. Each site became a charnel house choked with dead from both sides, men were stretched to the limit of their physical and mental endurance. On 15th September, at Flers, tanks were first used in battle. Few in number (49), mechanically unreliable and with no proven tactical plan for their best use, they did have a devastating effect - 4,000 yards were captured in one day. Haig and his Generals did not know how close they were to a breakthrough, so they kept the Cavalry in reserve. Of the 27 tanks that reached the front line only 3 were serviceable the next day. Conditions inside were appalling. Many succumbed to artillery fire, mechanical breakdown and uneven ground. Nevertheless, Haig ordered 1,000 more for future battles, he was grimly determined to keep pressure on his tenacious foe. The Battle of the Somme cost at least 128,000 British and Empire lives - an average of 900 a day. The community of Wilmslow alone was to lose 7 this month. Private Harold Austin of the 20th Battalion Manchester’s (17286) died on 3rd September 1916, aged 18. He had lived with his father Joseph (a salesman for a cotton manufacturer), mother Amelia and 2 brothers at Rydal Mount near Lindow Cricket Club and is commemorated at Thiepval, St John's, St Bartholomew’s and on the civic memorial. -

“ Far and Sure.”

“ Far and Sure.” ''Registered as a Newspaper.-) No. 214. Vol. V ili.] Price Twopence. FRIDAY, AUGUST 1894. [Copyright.] i.7t h , io.r. 6d. pet Annum, Post Free. Aug. 22.— Royal Cromer : Summer Meeting (Visitors only). Aug. 25.— West Herts : “ Bogey ” Competition. Troon : Sandhill Gold Medal. Holmes Chapel v. Heaton Moor. Windermere: Gentlemen; Monthly Competition. Royal West Norfolk : Monthly Medal. Ventnor : Saltarn Badge. Kemp Town : Monthly Medal. Headingley : Scratch Medal (Second Round). Royal Eastbourne : Monthly Medal. Chester : Handicap Prize. Buxton and High Peak : Monthly Medal. Royal North Devon : Monthly Medal. Cheadle : Silver and Bronze Medals. Alfreton : Bronze Medal. Alfreton Ladies : Silver Spoon. Warwickshire : Monthly Competition. Glamorganshire v. Weston. West Lancashire : Monthly Competition (Class II). Cinque Ports : Monthly Medal. Royal Cromer : Monthly Medal. Morecambe and Heysham : Monthly Prize. Aug. 18.— Troon : Ladies’ and Gentlemen’s Foursomes. Willesden : Monthly Medal. Windermere : Mr. Sladen’s Prize. Luffness : Captain’s and Club Prizes. Southend-on-Sea : Monthly Medal. Taplow : Monthly Medal. Fleetwood : Monthly Medal. Ilkley : Monthly Medal. North-West Club (Londonderry) : Ladies’ Monthly Medal. Lytham and St. Anne’s : The Hermon Prize. Headingley : Monthly Medal and Scratch Medal (First Neasden : Monthly Medal. Round). Marple : Club Medal and Captain's Cup. King’s Norton : Captain’s Prize. Dumfries and Galloway : Monthly Competition. Chester : Monthly Competition. Crookham : Monthly Medal. Cheadle v. Macclesfield. Royal Wimbledon : Monthly Medal. Formby : Monthly Optional Subscription Prize. Huddersfield : Monthly Competition. Redhill and Reigate : Silver Iron. Eltham Ladies : Monthly Medal (“ Bogey ”). Wakefield : Monthly Medal. West Cornw all: Monthly Medal. Sheffield and District : Captain’s Cup. Gullane : The Haldane Cup. Rochester: Monthly Medal. Rochester Ladies : Monthly Medal. -

Learning Lessons? Fifth Army Tank Operations, 1916-1917 – Jake Gasson

Learning Lessons? Fifth Army Tank Operations, 1916-1917 – Jake Gasson Introduction On 15 September 1916, a new weapon made its battlefield debut at Flers-Courcelette on the Somme – the tank. Its debut, primarily under the Fourth Army, has overshadowed later deployments of the tank on the Somme, particularly those under General Sir Hubert de la Poer Gough’s Reserve Army, or Fifth Army as it came to be known after 30 October 1916. Gough’s operations against Thiepval and beside the Ancre made small scale usage of tanks as auxiliaries to the infantry, but have largely been ignored in historiography.1 Similarly, Gough’s employment of tanks the following spring in April 1917 at Bullecourt has only been cursorily discussed for the Australian distrust in tanks created by the debacle.2 The value in examining these further is twofold. Firstly, the examination of operations on the Somme through the case studies of Thiepval and Beaumont-Hamel presents a more positive appraisal of the tank’s impact than analysis confined to Flers-Courcelette, such as J.F.C. Fuller’s suggestion that their impact was more as the ‘birthday of a new epoch’ on 15 September than concrete success.3 Secondly, Gough’s tank operations shed a new light onto the notion of the ‘learning curve’, the idea that the British Army became a more effective ‘instrument of war’ through its experience on the Somme.4 This goes beyond the well-trodden infantry and artillery tactics, and the study of campaigns in isolation. Gough’s operations from Thiepval to Bullecourt highlight the inter-relationship between theory and practice, the distinctive nature 1 David J. -

Stamp Has Described How Lutyens Designed the Memorial to the Missing of the Somme

‘Stamp has described how Lutyens designed the Memorial to the Missing of the Somme. His book is as restrained, and as “saturated in melancholy” as the monument itself. Far more than a work of pure architectural history, this beautifully poignant book illuminates the tragedy of the Great War, and tells us much about its aftermath. It is a truly classical piece of prose, a tragic chorus on the Somme which reverberates on the battlefields of today’ A. N. Wilson ‘A brilliant achievement … I felt instantly at one with [the] approach and treatment. It was such a clever idea … to treat Lutyens through Thiepval.’ John Keegan ‘An invaluable, detailed and illuminating study of how the memorial came to be built and how its effects are achieved’ Geoff Dyer, Guardian ‘Stamp’s book is devoted to a single one of the thousands of memorials that now dot the battlefield, Lutyens’s stupendous arch at Thiepval that records the names of over 73,000 British and South African soldiers who were killed on the Somme but have no known graves. As a piece of architectural analysis, it is impressive’ M. R. D. Foot, Spectator ‘A passionate and unusual book … [an] eloquent account of the genius of the vision of Lutyens … who created in the Monument to the Missing at Thiepval the central metaphor of a generation’s experience of appalling loss’ Tim Gardham, Observer ‘Moving and eloquent’ Nigel Jones, Literary Review ‘A book of remarkable emotional restraint’ Jonathan Meades, New Statesman ‘Gavin Stamp considers the building both as a piece of architecture and as a monument of profound cultural resonance’ London Review of Books ‘Succinct and masterly … [a] remarkable book’ Kenneth Powell, Architects Journal ‘Brilliantly lucid … Stamp is a marvellous writer, and brings every aspect of this monument and its story under lively scrutiny’ Jeremy Musson, Country Life ‘A poignant reminder’ Mark Bostridge, Independent on Sunday ‘The Memorial to the Missing of the Somme distils the first world war into the story of Lutyens’s great but under- celebrated monument at Thiepval. -

Hindenburgline Project

Newsletter #5 // december 2014 stichting.fondation.foundation.stiftung HIndenbuRglIne pRoject . UPDATE: We’re hard at work on the contents of our book and making . Team: Besides the collaboration of our excellent French translator, steady progress on both the text and the photography. As you know, our Valérie Charbey of Alphen a/d Rijn, we have also invited two other project is based on places described in diaries and letters written by translators (on the basis of sample translations) to enrich our soldiers who at some point were stationed on the Western Front, men who team: Hanna Kok-Ahrens (of Vertaalwerk Duits, Hilversum) for the never lost sight of their sense of humanity. We visited and photographed Dutch/German translation and Nancy Forest-Flier (of Forest-Flier a large number of those places in 2014: the ‘Westhoek’ of Belgium as well Editorial Services, Alkmaar) for the Dutch/English translation. The as northern France around Arras and the infamous Vimy Ridge, the area final editing of the book will be undertaken by the Dutch language northwest and south of Verdun and finally the area around Orbey in the specialist Josette van Heck of Tilburg. Vosges. This coming December we’ll be working around Péronne along the Somme. The accompanying map provides a brief glimpse of the places . Hindenburgline Project >> supported by (in progress) we’ve already visited or plan to visit (93 so far!), a selection of which will With a sympathetic contribution from the famous German firm be included in the book (around 50) and/or the exhibition. Leica Camera AG, and with the De Pont museum in Tilburg as our next partner in the project’s exhibition segment, we have come . -

Private William HALL Service Number: 25-1014 25Th Battalion Tyneside Irish Northumberland Fusiliers Died 1St July 1916 Aged 22

z Private William HALL Service Number: 25-1014 25th Battalion Tyneside Irish Northumberland Fusiliers st Died 1 July 1916 aged 22 Commemorated on Thiepval Memorial Pier and face 10B, 11B and 12B WW1 Centenary record of an Unknown Soldier Recruitment -Tyneside Irish 24th, 25th, 26th and 27th Service Battalions of the Northumberland Fusiliers. Private William HALL was a member of the 25th Tyneside Irish Service Battalion. This was a ‘Pals’ regiment of the Northumberland Fusiliers, raised in the North East at the end of 1914. Enrolment was slow and a meeting was arranged for the 31st of October to shame those who had not enrolled. Over 100 men enrolled at the meeting and by November 2nd the Battalion was over 900. On the 4th of November the Battalion was full (1,737) By the 10th of November a second battalion (1,547) was officially sanctioned and within two days, the battalion was almost full. The War Office sanctioned a third battalion (1,487) and then a fourth battalion (1,560) creating a Tyneside Irish Brigade. In 96 days the Tyneside Irish had managed to recruit 5,331soldiers. Battle of the Somme The plan was for the British forces to attack on a fourteen-mile front after an intense week-long artillery bombardment of the German positions. Over 1.6 million shells were fired, 70 for every one metre of front, the idea being to decimate the German Front Line. Two minutes before zero-hour, 19 mines were exploded under the German lines. Whistles sounded and the troops went over the top at 7.30am. -

Beaumont-Hamel and the Battle of the Somme, Onwas Them, Trained a Few and Most Were Minutes Within Killed of the Assault

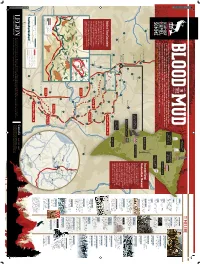

2015-12-18 2:03 PM Hunter’s CWGC TIMELINE Cemetery 1500s June 1916 English fishermen establish The regiment trains seasonal camps in Newfoundland in the rain and mud, waiting for the start of the Battle of the Somme 1610 The Newfoundland Company June 28, 1916 Hawthorn 51st (Highland) starts a proprietary colony at Cuper’s Cove near St. John’s The regiment is ordered A century ago, the Newfoundland Regiment suffered staggering losses at Beaumont-Hamel in France Ridge No. 2 Division under a mercantile charter to move to a forward CWGC Cemetery Monument granted by Queen Elizabeth I trench position, but later at the start of the Battle of the Somme on July 1, 1916. At the moment of their attack, the Newfoundlanders that day the order is postponed July 23-Aug. 7, 1916 were silhouetted on the horizon and the Germans could see them coming. Every German gun in the area 1795 Battle of Pozières Ridge was trained on them, and most were killed within a few minutes of the assault. German front line Newfoundland’s first military regiment is founded 9:15 p.m., June 30 September 1916 For more on the Newfoundland Regiment, Beaumont-Hamel and the Battle of the Somme, to 2 a.m., July 1, 1916 Canadian troops, moved from go to www.legionmagazine.com/BloodInTheMud. 1854 positions near Ypres, begin Newfoundland becomes a crown The regiment marches 12 kilo- arriving at the Somme battlefield Y Ravine CWGC colony of the British Empire metres to its designated trench, Cemetery dubbed St. John’s Road Sept.