Parasite Findings in Archeological Remains: a Paleogeographic View 20

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gastrointestinal Helminthic Parasites of Habituated Wild Chimpanzees

Aus dem Institut für Parasitologie und Tropenveterinärmedizin des Fachbereichs Veterinärmedizin der Freien Universität Berlin Gastrointestinal helminthic parasites of habituated wild chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus) in the Taï NP, Côte d’Ivoire − including characterization of cultured helminth developmental stages using genetic markers Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Veterinärmedizin an der Freien Universität Berlin vorgelegt von Sonja Metzger Tierärztin aus München Berlin 2014 Journal-Nr.: 3727 Gedruckt mit Genehmigung des Fachbereichs Veterinärmedizin der Freien Universität Berlin Dekan: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Jürgen Zentek Erster Gutachter: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Georg von Samson-Himmelstjerna Zweiter Gutachter: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Heribert Hofer Dritter Gutachter: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Achim Gruber Deskriptoren (nach CAB-Thesaurus): chimpanzees, helminths, host parasite relationships, fecal examination, characterization, developmental stages, ribosomal RNA, mitochondrial DNA Tag der Promotion: 10.06.2015 Contents I INTRODUCTION ---------------------------------------------------- 1- 4 I.1 Background 1- 3 I.2 Study objectives 4 II LITERATURE OVERVIEW --------------------------------------- 5- 37 II.1 Taï National Park 5- 7 II.1.1 Location and climate 5- 6 II.1.2 Vegetation and fauna 6 II.1.3 Human pressure and impact on the park 7 II.2 Chimpanzees 7- 12 II.2.1 Status 7 II.2.2 Group sizes and composition 7- 9 II.2.3 Territories and ranging behavior 9 II.2.4 Diet and hunting behavior 9- 10 II.2.5 Contact with humans 10 II.2.6 -

F. Moravec: Trichinelloid Nematodes Parasitic in Cold-Blooded Vertebrates

FOLIA PARASITOLOGICA 49: 24, 2002 F. Moravec: Trichinelloid Nematodes Parasitic in Cold-blooded Vertebrates. Academia, Praha, 2001. ISBN 80-200-0805-5, hardback, 430 pp., 138 figs. Price CZK (Czech crowns) 395.00. The author of this monograph, Dr. František Moravec, their synonymy, description with illustrations, data on hosts, DrSc., of the Institute of Parasitology, Academy of Sciences locations, distribution and biology. The original comments on of the Czech Republic, České Budějovice (South Bohemia) is the nomenclature history, synonymy, morphological variabil- one of the world’s foremost authorities on parasitic nema- ity, differentiation and other aspects are indeed very valuable. todes, whose numerous classic papers and monographs on the In this way, the author assesses in detail 78 nematode species systematics and biology of this important parasite group are from fish, l5 from amphibians and 22 from reptiles. both well-known and internationally recognised. Consequently, the above conception, based on Moravec’s The content being assessed is devoted to morphology, (1982) originally modified classification system of capil- systematics, taxonomy and to other aspects of the parasite-host lariids, is used in the present book. The text of the book is relations within the large group of trichinelloid (mainly supplemented with a parasite-host list containing 347 fish, 47 capillariid) nematodes that parasitise cold-blooded animals on amphibian and 55 reptile species. The bibliography included a world-wide scale. The monograph contains detailed contains 669 citations of the literature sources. information on the methods of studying these parasites, their The monograph as a whole is of a high standard, much morphology, systematic value of individual features and on enhanced by good graphics and layout. -

Área Biológica Y Biomédica

UNIVERSIDAD TÉCNICA PARTICULAR DE LOJA La Universidad Católica de Loja ÁREA BIOLÓGICA Y BIOMÉDICA TITULO DE BIÓLOGO Análisis de la composición de la dieta de Lagidium ahuacaense TRABAJO DE TITULACIÓN Autor: Sarango Peláez Bryan Daniel Director: Cisneros Vidal Rodrigo, Mgtr. LOJA – ECUADOR 2018 CARATULA I Esta versión digital, ha sido acreditada bajo la licencia Creative Commons 4.0, CC BY-NY- SA: Reconocimiento-No comercial-Compartir igual; la cual permite copiar, distribuir y comunicar públicamente la obra, mientras se reconozca la autoría original, no se utilice con fines comerciales y se permiten obras derivadas, siempre que mantenga la misma licencia al ser divulgada. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/deed.es 2018 CERTIFICACIÓN APROBACIÓN DEL DIRECTOR DEL TRABAJO DE TITULACIÓN Mgtr. Rodrigo Cisneros Vidal DOCENTE DE LA TITULACIÓN De mi consideración: El presente trabajo de fin de titulación: Análisis de la composición de la dieta de Lagidium ahuacaense realizado por Bryan Daniel Sarango Peláez; ha sido orientado y revisado durante su ejecución, por cuanto se aprueba la presentación del mismo. Loja, septiembre del 2018 f). ………………………………………………………………………………………………………… II DECLARACIÓN DE AUTORÍA Y CESIÓN DE DERECHOS “Yo Bryan Daniel Sarango Peláez declaro ser el autor (a) del presente trabajo de fin de titulación: Análisis de la composición de la dieta de Lagidium ahuacaense, de la titulación Biólogo siendo Mgtr. Rodrigo Cisneros Vidal director del presente trabajo; y eximo expresamente a la Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja y a sus representantes legales de posibles reclamos o acciones legales. Además, certifico que las ideas, conceptos, procedimientos y resultados vertidos en el presente trabajo investigativo, son de mi exclusiva responsabilidad. -

Fishery Bulletin/U S Dept of Commerce National Oceanic

Abstract.-Seventeen species of parasites representing the Cestoda, Parasite Fauna of Three Species Nematoda, Acanthocephala, and Crus tacea are reported from three spe of Antarctic Whales with cies of Antarctic whales. Thirty-five sei whales Balaenoptera borealis, Reference to Their Use 106 minke whales B. acutorostrata, and 35 sperm whales Pkyseter cato as Potentia' Stock Indicators don were examined from latitudes 30° to 64°S, and between longitudes 106°E to 108°W, during the months Murray D. Dailey ofNovember to March 1976-77. Col Ocean Studies Institute. California State University lection localities and regional hel Long Beach, California 90840 minth fauna diversity are plotted on distribution maps. Antarctic host-parasite records from Wolfgang K. Vogelbein B. borealis, B. acutorostrata, and P. Virginia Institute of Marine Science catodon are updated and tabulated Gloucester Point. Virginia 23062 by commercial whaling sectors. The use of acanthocephalan para sites of the genus Corynosoma as potential Antarctic sperm whale stock indicators is discussed. The great whales of the southern hemi easiest to find (Gaskin 1976). A direct sphere migrate annually between result of this has been the successive temperate breeding and Antarctic overexploitation of several major feeding grounds. However, results of whale species. To manage Antarctic Antarctic whale tagging programs whaling more effectively, identifica (Brown 1971, 1974, 1978; Ivashin tion and determination of whale 1988) indicate that on the feeding stocks is of high priority (Schevill grounds circumpolar movement by 1971, International Whaling Com sperm and baleen whales is minimal. mission 1990). These whales apparently do not com The Antarctic whaling grounds prise homogeneous populations were partitioned by the International whose members mix freely through Whaling Commission into commer out the entire Antarctic. -

Redalyc.NEW HOST RECORDS and GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION OF

Mastozoología Neotropical ISSN: 0327-9383 [email protected] Sociedad Argentina para el Estudio de los Mamíferos Argentina Robles, María del Rosario; Navone, Graciela T. NEW HOST RECORDS AND GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION OF SPECIES OF Trichuris (NEMATODA: TRICHURIIDAE) IN RODENTS FROM ARGENTINA WITH AN UPDATED SUMMARY OF RECORDS FROM AMERICA Mastozoología Neotropical, vol. 21, núm. 1, 2014, pp. 67-78 Sociedad Argentina para el Estudio de los Mamíferos Tucumán, Argentina Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=45731230008 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Mastozoología Neotropical, 21(1):67-78, Mendoza, 2014 Copyright ©SAREM, 2014 Versión impresa ISSN 0327-9383 http://www.sarem.org.ar Versión on-line ISSN 1666-0536 Artículo NEW HOST RECORDS AND GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION OF SPECIES OF Trichuris (NEMATODA: TRICHURIIDAE) IN RODENTS FROM ARGENTINA WITH AN UPDATED SUMMARY OF RECORDS FROM AMERICA María del Rosario Robles and Graciela T. Navone Centro de Estudios Parasitológicos y de Vectores CEPAVE (CCT-CONICET La Plata) (UNLP), Calle 2 # 584, (1900) La Plata, Buenos Aires, Argentina [correspondence: María del Rosario Robles <[email protected]>]. ABSTRACT. Species of Trichuris have a cosmopolitan distribution and parasitize a broad range of mammalian hosts. Although, the prevalence and intensity of this genus depends on many factors, the life cycles and char- acteristics of the environment have been the main aspect used to explain their geographical distribution. In this paper, we provide new host and geographical records for the species of Trichuris from Sigmodontinae rodents in Argentina. -

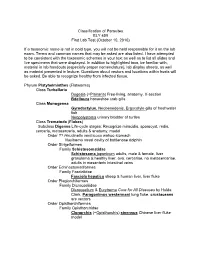

Classification of Parasites BLY 459 First Lab Test (October 10, 2010)

Classification of Parasites BLY 459 First Lab Test (October 10, 2010) If a taxonomic name is not in bold type, you will not be held responsible for it on the lab exam. Terms and common names that may be asked are also listed. I have attempted to be consistent with the taxonomic schemes in your text as well as to list all slides and live specimens that were displayed. In addition to highlighted taxa, be familiar with, material in lab handouts (especially proper nomenclature), lab display sheets, as well as material presented in lecture. Questions about vectors and locations within hosts will be asked. Be able to recognize healthy from infected tissue. Phylum Platyhelminthes (Flatworms) Class Turbellaria Dugesia (=Planaria ) Free-living, anatomy, X-section Bdelloura horseshoe crab gills Class Monogenea Gyrodactylus , Neobenedenis, Ergocotyle gills of freshwater fish Neopolystoma urinary bladder of turtles Class Trematoda ( Flukes ) Subclass Digenea Life-cycle stages: Recognize miracidia, sporocyst, redia, cercaria , metacercaria, adults & anatomy, model Order ?? Hirudinella ventricosa wahoo stomach Nasitrema nasal cavity of bottlenose dolphin Order Strigeiformes Family Schistosomatidae Schistosoma japonicum adults, male & female, liver granuloma & healthy liver, ova, cercariae, no metacercariae, adults in mesenteric intestinal veins Order Echinostomatiformes Family Fasciolidae Fasciola hepatica sheep & human liver, liver fluke Order Plagiorchiformes Family Dicrocoeliidae Dicrocoelium & Eurytrema Cure for All Diseases by Hulda Clark, Paragonimus -

Review and Meta-Analysis of the Environmental Biology and Potential Invasiveness of a Poorly-Studied Cyprinid, the Ide Leuciscus Idus

REVIEWS IN FISHERIES SCIENCE & AQUACULTURE https://doi.org/10.1080/23308249.2020.1822280 REVIEW Review and Meta-Analysis of the Environmental Biology and Potential Invasiveness of a Poorly-Studied Cyprinid, the Ide Leuciscus idus Mehis Rohtlaa,b, Lorenzo Vilizzic, Vladimır Kovacd, David Almeidae, Bernice Brewsterf, J. Robert Brittong, Łukasz Głowackic, Michael J. Godardh,i, Ruth Kirkf, Sarah Nienhuisj, Karin H. Olssonh,k, Jan Simonsenl, Michał E. Skora m, Saulius Stakenas_ n, Ali Serhan Tarkanc,o, Nildeniz Topo, Hugo Verreyckenp, Grzegorz ZieRbac, and Gordon H. Coppc,h,q aEstonian Marine Institute, University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia; bInstitute of Marine Research, Austevoll Research Station, Storebø, Norway; cDepartment of Ecology and Vertebrate Zoology, Faculty of Biology and Environmental Protection, University of Lodz, Łod z, Poland; dDepartment of Ecology, Faculty of Natural Sciences, Comenius University, Bratislava, Slovakia; eDepartment of Basic Medical Sciences, USP-CEU University, Madrid, Spain; fMolecular Parasitology Laboratory, School of Life Sciences, Pharmacy and Chemistry, Kingston University, Kingston-upon-Thames, Surrey, UK; gDepartment of Life and Environmental Sciences, Bournemouth University, Dorset, UK; hCentre for Environment, Fisheries & Aquaculture Science, Lowestoft, Suffolk, UK; iAECOM, Kitchener, Ontario, Canada; jOntario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, Peterborough, Ontario, Canada; kDepartment of Zoology, Tel Aviv University and Inter-University Institute for Marine Sciences in Eilat, Tel Aviv, -

From Skin of Red Snapper, Lutjanus Campechanus (Perciformes: Lutjanidae), on the Texas–Louisiana Shelf, Northern Gulf of Mexico

J. Parasitol., 99(2), 2013, pp. 318–326 Ó American Society of Parasitologists 2013 A NEW SPECIES OF TRICHOSOMOIDIDAE (NEMATODA) FROM SKIN OF RED SNAPPER, LUTJANUS CAMPECHANUS (PERCIFORMES: LUTJANIDAE), ON THE TEXAS–LOUISIANA SHELF, NORTHERN GULF OF MEXICO Carlos F. Ruiz, Candis L. Ray, Melissa Cook*, Mark A. Grace*, and Stephen A. Bullard Aquatic Parasitology Laboratory, Department of Fisheries and Allied Aquacultures, College of Agriculture, Auburn University, 203 Swingle Hall, Auburn, Alabama 36849. Correspondence should be sent to: [email protected] ABSTRACT: Eggs and larvae of Huffmanela oleumimica n. sp. infect red snapper, Lutjanus campechanus (Poey, 1860), were collected from the Texas–Louisiana Shelf (28816036.5800 N, 93803051.0800 W) and are herein described using light and scanning electron microscopy. Eggs in skin comprised fields (1–5 3 1–12 mm; 250 eggs/mm2) of variously oriented eggs deposited in dense patches or in scribble-like tracks. Eggs had clear (larvae indistinct, principally vitelline material), amber (developing larvae present) or brown (fully developed larvae present; little, or no, vitelline material) shells and measured 46–54 lm(x¼50; SD 6 1.6; n¼213) long, 23–33 (27 6 1.4; 213) wide, 2–3 (3 6 0.5; 213) in eggshell thickness, 18–25 (21 6 1.1; 213) in vitelline mass width, and 36–42 (39 6 1.1; 213) in vitelline mass length with protruding polar plugs 5–9 (7 6 0.6; 213) long and 5–8 (6 6 0.5; 213) wide. Fully developed larvae were 160–201 (176 6 7.9) long and 7–8 (7 6 0.5) wide, had transverse cuticular ridges, and were emerging from some eggs within and beneath epidermis. -

Worms, Nematoda

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology Parasitology, Harold W. Manter Laboratory of 2001 Worms, Nematoda Scott Lyell Gardner University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/parasitologyfacpubs Part of the Parasitology Commons Gardner, Scott Lyell, "Worms, Nematoda" (2001). Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology. 78. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/parasitologyfacpubs/78 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Parasitology, Harold W. Manter Laboratory of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in Encyclopedia of Biodiversity, Volume 5 (2001): 843-862. Copyright 2001, Academic Press. Used by permission. Worms, Nematoda Scott L. Gardner University of Nebraska, Lincoln I. What Is a Nematode? Diversity in Morphology pods (see epidermis), and various other inverte- II. The Ubiquitous Nature of Nematodes brates. III. Diversity of Habitats and Distribution stichosome A longitudinal series of cells (sticho- IV. How Do Nematodes Affect the Biosphere? cytes) that form the anterior esophageal glands Tri- V. How Many Species of Nemata? churis. VI. Molecular Diversity in the Nemata VII. Relationships to Other Animal Groups stoma The buccal cavity, just posterior to the oval VIII. Future Knowledge of Nematodes opening or mouth; usually includes the anterior end of the esophagus (pharynx). GLOSSARY pseudocoelom A body cavity not lined with a me- anhydrobiosis A state of dormancy in various in- sodermal epithelium. -

Possible Influence of the ENSO Phenomenon on the Pathoecology

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Karl Reinhard Papers/Publications Natural Resources, School of 2010 Possible influence of the ENSO phenomenon on the pathoecology of diphyllobothriasis and anisakiasis in ancient Chinchorro populations Bernardo Arriaza Universidad de Tarapacá, [email protected] Karl Reinhard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Adauto Araujo Escola Nacional de Saúde Pública-Fiocruz, [email protected] Nancy C. Orellana Convenio de Desempeño Vivien G. Standen Universidad de Tarapacá, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natresreinhard Arriaza, Bernardo; Reinhard, Karl; Araujo, Adauto; Orellana, Nancy C.; and Standen, Vivien G., "Possible influence of the ENSO phenomenon on the pathoecology of diphyllobothriasis and anisakiasis in ancient Chinchorro populations" (2010). Karl Reinhard Papers/Publications. 10. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natresreinhard/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Natural Resources, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Karl Reinhard Papers/Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 66 Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de Janeiro, Vol. 105(1): 66-72, February 2010 Possible influence of the ENSO phenomenon on the pathoecology of diphyllobothriasis and anisakiasis in ancient Chinchorro populations Bernardo T Arriaza1/+, Karl J Reinhard2, Adauto -

Nuevas Localidades Para Tres Especies De Mamíferos Pequeños (Rodentia: Cricetidae) Escasamente Conocidos En Ecuador

Mastozoología Neotropical, 23(2):521-527, Mendoza, 2016 Copyright ©SAREM, 2016 http://www.sarem.org.ar Versión impresa ISSN 0327-9383 http://www.sbmz.com.br Versión on-line ISSN 1666-0536 Nota NUEVAS LOCALIDADES PARA TRES ESPECIES DE MAMÍFEROS PEQUEÑOS (RODENTIA: CRICETIDAE) ESCASAMENTE CONOCIDOS EN ECUADOR Jorge Brito1 y Alfonso Arguero2 1 Museo Ecuatoriano de Ciencias Naturales del Instituto Nacional de Biodiversidad, División de Mastozoología, Calle Rumipamba 341 y Av. de Los Shyris, casilla postal 17-07-8976, Quito, Ecuador. [Correspondencia: Jorge Brito <[email protected]>]. 2 Instituto de Ciencias Biológicas, Escuela Politécnica Nacional, Av. Ladrón de Guevara E-11 253 e Isabel la Católica, Casilla postal 17-01-2759, Quito, Ecuador. RESUMEN. En este trabajo se documentan nuevas localidades para tres especies de mamíferos pequeños escasamente conocidos en Ecuador, en base a colectas de campo y revisión de colecciones mastozoológicas. Reportamos la ampliación del rango de distribución de Tanyuromys aphrastus, Thomasomys fumeus y T. hudsoni. En Ecuador es necesario incrementar muestreos en las laderas de los Andes, con la finalidad de obtener una mejor documentación de la riqueza y distribución de los mamíferos pequeños. ABSTRACT. New localities for three poorly known species of small mammals (Rodentia: Cricetidae). On the basis of field efforts and a review of mammal collections, we report new localities in Ecuador for three rare small mammal species. We report extensions of the ranges of distribution for Tanyuromys aphrastus, Thomasomys fumeus and Thomasomys hudsoni. The Ecuatorian Andean region requires additional sampling efforts, in order to better document the richness and distribution of small mammals. Palabras clave: Tanyuromys aphrastus. -

Morphological and Molecular Studies of Moniezia Sp

RESEARCH PAPER Zoology Volume : 5 | Issue : 8 | August 2015 | ISSN - 2249-555X Morphological and Molecular Studies of Moniezia Sp. (Cestoda: Anaplocephalidea) A Parasite of the Domestic Goat Capra Hircus (L.) in Aurangabad District (M.S.), India. KEYWORDS Anaplocephalidea, Aurangabad, Capra hircus, India, Moniezia. Amol Thosar Ganesh Misal Department of Zoology, Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Department of Zoology, Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Marathwada University, Aurangabad - 431004 Marathwada University, Aurangabad - 431004 Arun Gaware Sunita Borde Department of Zoology, Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Department of Zoology, Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Marathwada University, Aurangabad-431004. Marathwada University, Aurangabad-431004. ABSTRACT Moniezia Sp.Nov. (Cestoda: Anaplocephalidea) is collected in the intestine of Capra hircus, Linnaeus, 1758 (Family: Bovidae) from Aurangabad district (M.S.), India. The present Cestode i.e. Moniezia Sp. Nov. differs other all known species is having the scolex almost squarish, mature proglottids nearly five times broader than long, Craspedote in shape, testes small in size, round to oval, 210-220 in numbers, cirrus pouch oval, ovary horse-shoe shaped, vitelline gland post ovarian.In molecular characterization of the parasites, the genomic DNA were amplified and sequenced. Based upon both morphological data and molecular analysis using bioinformatics tools, the Cestode is identified as confirmed to be representing Moniezia Sp. in mammalian host i.e. Goat. INTRODUCTION among individual orders. In addition to morphological The genus Moniezia was established by Blanchard, 1891. characters that are often variable, difficult to homologies, Skrjabin and Schulz (1937) divided this genus in to three molecular data have been widely used in phylogenetic subgenera as follows: studies of Cestodes generally and these Cestodes particu- larly using many genes and developed techniques as at- 1) Inter proglottidal glands grouped in rosettes--------------- tempts in solving many taxonomic problem.