Possible Influence of the ENSO Phenomenon on the Pathoecology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Globalization and Infectious Diseases: a Review of the Linkages

TDR/STR/SEB/ST/04.2 SPECIAL TOPICS NO.3 Globalization and infectious diseases: A review of the linkages Social, Economic and Behavioural (SEB) Research UNICEF/UNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Programme for Research & Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR) The "Special Topics in Social, Economic and Behavioural (SEB) Research" series are peer-reviewed publications commissioned by the TDR Steering Committee for Social, Economic and Behavioural Research. For further information please contact: Dr Johannes Sommerfeld Manager Steering Committee for Social, Economic and Behavioural Research (SEB) UNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR) World Health Organization 20, Avenue Appia CH-1211 Geneva 27 Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] TDR/STR/SEB/ST/04.2 Globalization and infectious diseases: A review of the linkages Lance Saker,1 MSc MRCP Kelley Lee,1 MPA, MA, D.Phil. Barbara Cannito,1 MSc Anna Gilmore,2 MBBS, DTM&H, MSc, MFPHM Diarmid Campbell-Lendrum,1 D.Phil. 1 Centre on Global Change and Health London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Keppel Street, London WC1E 7HT, UK 2 European Centre on Health of Societies in Transition (ECOHOST) London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Keppel Street, London WC1E 7HT, UK TDR/STR/SEB/ST/04.2 Copyright © World Health Organization on behalf of the Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases 2004 All rights reserved. The use of content from this health information product for all non-commercial education, training and information purposes is encouraged, including translation, quotation and reproduction, in any medium, but the content must not be changed and full acknowledgement of the source must be clearly stated. -

Fishery Bulletin/U S Dept of Commerce National Oceanic

Abstract.-Seventeen species of parasites representing the Cestoda, Parasite Fauna of Three Species Nematoda, Acanthocephala, and Crus tacea are reported from three spe of Antarctic Whales with cies of Antarctic whales. Thirty-five sei whales Balaenoptera borealis, Reference to Their Use 106 minke whales B. acutorostrata, and 35 sperm whales Pkyseter cato as Potentia' Stock Indicators don were examined from latitudes 30° to 64°S, and between longitudes 106°E to 108°W, during the months Murray D. Dailey ofNovember to March 1976-77. Col Ocean Studies Institute. California State University lection localities and regional hel Long Beach, California 90840 minth fauna diversity are plotted on distribution maps. Antarctic host-parasite records from Wolfgang K. Vogelbein B. borealis, B. acutorostrata, and P. Virginia Institute of Marine Science catodon are updated and tabulated Gloucester Point. Virginia 23062 by commercial whaling sectors. The use of acanthocephalan para sites of the genus Corynosoma as potential Antarctic sperm whale stock indicators is discussed. The great whales of the southern hemi easiest to find (Gaskin 1976). A direct sphere migrate annually between result of this has been the successive temperate breeding and Antarctic overexploitation of several major feeding grounds. However, results of whale species. To manage Antarctic Antarctic whale tagging programs whaling more effectively, identifica (Brown 1971, 1974, 1978; Ivashin tion and determination of whale 1988) indicate that on the feeding stocks is of high priority (Schevill grounds circumpolar movement by 1971, International Whaling Com sperm and baleen whales is minimal. mission 1990). These whales apparently do not com The Antarctic whaling grounds prise homogeneous populations were partitioned by the International whose members mix freely through Whaling Commission into commer out the entire Antarctic. -

Opisthorchiasis: an Emerging Foodborne Helminthic Zoonosis of Public Health Significance

IJMPES International Journal of http://ijmpes.com doi 10.34172/ijmpes.2020.27 Medical Parasitology & Vol. 1, No. 4, 2020, 101-104 eISSN 2766-6492 Epidemiology Sciences Review Article Opisthorchiasis: An Emerging Foodborne Helminthic Zoonosis of Public Health Significance Mahendra Pal1* ID , Dimitri Ketchakmadze2 ID , Nino Durglishvili3 ID , Yagoob Garedaghi4 ID 1Narayan Consultancy on Veterinary Public Health and Microbiology, Gujarat, India 2Faculty of Chemical Technologies and Metallurgy, Georgian Technical University, Tbilisi, Georgia 3Department of Sociology and Social Work, Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, Tbilisi, Georgia 4Department of Parasitology, Tabriz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tabriz, Iran Abstract Opisthorchiasis is an emerging foodborne parasitic zoonosis that has been reported from developing as well as developed nations of the world. Globally, around 80 million people are at risk of acquiring Opisthorchis infection. The source of infection is exogenous, and ingestion is considered as the primary mode of transmission. Humans get the infection by consuming raw or undercooked fish. In most cases, the infection remains asymptomatic. However, in affected individuals, the clinical manifestations are manifold. Occasionally, complications including cholangitis, cholecystitis, and cholangiocarcinoma are observed. The people who have the dietary habit of eating raw fish usually get the infection. Certain occupational groups, such as fishermen, agricultural workers, river fleet employees, and forest industry personnel are mainly infected with Opisthorchis. The travelers to the endemic regions who consume raw fish are exposed to the infection. Parasitological, immunological, and molecular techniques are employed to confirm the diagnosis of disease. Treatment regimens include oral administration of praziquantel and albendazole. In the absence of therapy, the acute phase transforms into a chronic one that may persist for two decades. -

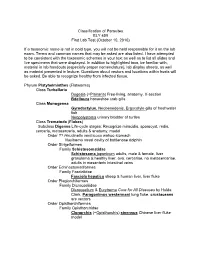

Classification of Parasites BLY 459 First Lab Test (October 10, 2010)

Classification of Parasites BLY 459 First Lab Test (October 10, 2010) If a taxonomic name is not in bold type, you will not be held responsible for it on the lab exam. Terms and common names that may be asked are also listed. I have attempted to be consistent with the taxonomic schemes in your text as well as to list all slides and live specimens that were displayed. In addition to highlighted taxa, be familiar with, material in lab handouts (especially proper nomenclature), lab display sheets, as well as material presented in lecture. Questions about vectors and locations within hosts will be asked. Be able to recognize healthy from infected tissue. Phylum Platyhelminthes (Flatworms) Class Turbellaria Dugesia (=Planaria ) Free-living, anatomy, X-section Bdelloura horseshoe crab gills Class Monogenea Gyrodactylus , Neobenedenis, Ergocotyle gills of freshwater fish Neopolystoma urinary bladder of turtles Class Trematoda ( Flukes ) Subclass Digenea Life-cycle stages: Recognize miracidia, sporocyst, redia, cercaria , metacercaria, adults & anatomy, model Order ?? Hirudinella ventricosa wahoo stomach Nasitrema nasal cavity of bottlenose dolphin Order Strigeiformes Family Schistosomatidae Schistosoma japonicum adults, male & female, liver granuloma & healthy liver, ova, cercariae, no metacercariae, adults in mesenteric intestinal veins Order Echinostomatiformes Family Fasciolidae Fasciola hepatica sheep & human liver, liver fluke Order Plagiorchiformes Family Dicrocoeliidae Dicrocoelium & Eurytrema Cure for All Diseases by Hulda Clark, Paragonimus -

Broad Tapeworms (Diphyllobothriidae)

IJP: Parasites and Wildlife 9 (2019) 359–369 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect IJP: Parasites and Wildlife journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijppaw Broad tapeworms (Diphyllobothriidae), parasites of wildlife and humans: T Recent progress and future challenges ∗ Tomáš Scholza, ,1, Roman Kuchtaa,1, Jan Brabeca,b a Institute of Parasitology, Biology Centre of the Czech Academy of Sciences, Branišovská 31, 370 05, České Budějovice, Czech Republic b Natural History Museum of Geneva, PO Box 6434, CH-1211, Geneva 6, Switzerland ABSTRACT Tapeworms of the family Diphyllobothriidae, commonly known as broad tapeworms, are predominantly large-bodied parasites of wildlife capable of infecting humans as their natural or accidental host. Diphyllobothriosis caused by adults of the genera Dibothriocephalus, Adenocephalus and Diphyllobothrium is usually not a life-threatening disease. Sparganosis, in contrast, is caused by larvae (plerocercoids) of species of Spirometra and can have serious health consequences, exceptionally leading to host's death in the case of generalised sparganosis caused by ‘Sparganum proliferum’. While most of the definitive wildlife hosts of broad tapeworms are recruited from marine and terrestrial mammal taxa (mainly carnivores and cetaceans), only a few diphyllobothriideans mature in fish-eating birds. In this review, we provide an overview the recent progress in our understanding of the diversity, phylogenetic relationships and distribution of broad tapeworms achieved over the last decade and outline the prospects of future research. The multigene family-wide phylogeny of the order published in 2017 allowed to propose an updated classi- fication of the group, including new generic assignment of the most important causative agents of human diphyllobothriosis, i.e., Dibothriocephalus latus and D. -

Identity of Diphyllobothrium Spp. (Cestoda: Diphyllobothriidae) from Sea Lions and People Along the Pacific Coast of South America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology Parasitology, Harold W. Manter Laboratory of 4-2010 Identity of Diphyllobothrium spp. (Cestoda: Diphyllobothriidae) from Sea Lions and People along the Pacific Coast of South America Robert L. Rausch University of Washington, [email protected] Ann M. Adams United States Food and Drug Administration Leo Margolis Fisheries Research Board of Canada Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/parasitologyfacpubs Part of the Parasitology Commons Rausch, Robert L.; Adams, Ann M.; and Margolis, Leo, "Identity of Diphyllobothrium spp. (Cestoda: Diphyllobothriidae) from Sea Lions and People along the Pacific Coast of South America" (2010). Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology. 498. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/parasitologyfacpubs/498 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Parasitology, Harold W. Manter Laboratory of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. J. Parasitol., 96(2), 2010, pp. 359–365 F American Society of Parasitologists 2010 IDENTITY OF DIPHYLLOBOTHRIUM SPP. (CESTODA: DIPHYLLOBOTHRIIDAE) FROM SEA LIONS AND PEOPLE ALONG THE PACIFIC COAST OF SOUTH AMERICA Robert L. Rausch, Ann M. Adams*, and Leo MargolisÀ Department of Comparative Medicine and Department of Pathobiology, Box 357190, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington 98195-7190. e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: Host specificity evidently is not expressed by various species of Diphyllobothrium that occur typically in marine mammals, and people become infected occasionally when dietary customs favor ingestion of plerocercoids. -

Parasite Findings in Archeological Remains: a Paleogeographic View 20

Part III - Parasite Findings in Archeological Remains: a paleogeographic view 20. The Findings in South America Luiz Fernando Ferreira Léa Camillo-Coura Martín H. Fugassa Marcelo Luiz Carvalho Gonçalves Luciana Sianto Adauto Araújo SciELO Books / SciELO Livros / SciELO Libros FERREIRA, L.F., et al. The Findings in South America. In: FERREIRA, L.F., REINHARD, K.J., and ARAÚJO, A., ed. Foundations of Paleoparasitology [online]. Rio de Janeiro: Editora FIOCRUZ, 2014, pp. 307-339. ISBN: 978-85-7541-598-6. Available from: doi: 10.7476/9788575415986.0022. Also available in ePUB from: http://books.scielo.org/id/zngnn/epub/ferreira-9788575415986.epub. All the contents of this work, except where otherwise noted, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license. Todo o conteúdo deste trabalho, exceto quando houver ressalva, é publicado sob a licença Creative Commons Atribição 4.0. Todo el contenido de esta obra, excepto donde se indique lo contrario, está bajo licencia de la licencia Creative Commons Reconocimento 4.0. The Findings in South America 305 The Findings in South America 20 The Findings in South America Luiz Fernando Ferreira • Léa Camillo-Coura • Martín H. Fugassa Marcelo Luiz Carvalho Gonçalves • Luciana Sianto • Adauto Araújo n South America, paleoparasitology first developed with studies in Brazil, consolidating this new science that Ireconstructs past events in the parasite-host relationship. Many studies on parasites in South American archaeological material were conducted on human mummies from the Andes (Ferreira, Araújo & Confalonieri, 1988). However, interest also emerged in parasites of animals, with studies of coprolites found in archaeological layers as a key source of ancient climatic data (Araújo, Ferreira & Confalonieri, 1982). -

Diphyllobothrium, Diseases of Wild and Cultured Fishes in Alaska

HELMINTHS Diphyllobothrium I. Causative Agent and Disease predatory fish that become paratenic Six species of diphyllobothrid ces- hosts when other infested fish are eaten. todes (tapeworm) occur in Alaska, all of The life cycle is complete when the fish which use fish as a second intermediate host is eaten by a mammal or bird defini- and/or as a paratenic host. Three species tive host where the worm becomes an of larval Diphyllobothrium that most egg-producing adult. commonly occur in Alaskan salmonid fishes include D. ditremum, dendriticum V. Diagnosis and nihonkaiense. The cestode larvae Diagnosis is made by visual identi- can be found free in the visceral cavity fication of the cestode during necropsy or encysted in the viscera or muscle tis- of a parasitized fish. Plerocercoid stages sues. of Diphyllobothrium have a compressed scolex with characteristic bothria or II. Host Species grooves. The body is usually slightly Planktivorous and carnivorous fresh- wrinkled, suggesting segmentation. PCR water fishes are potential hosts in North/ has been useful in confirming species South America and Eurasia including that has resulted in changing taxonomy. salmonids, whitefish, perch, northern pike, sticklebacks, burbot, and blackfish. VI. Prognosis for Host Prognosis for the host is good pro- III. Clinical Signs vided the infestation is low and there are The larval Diphyllobothrium can not other stressors involved. Juvenile fish be found (sometimes encysted) in the are more adversely affected than older muscles, viscera and connective tis- fish and can die from severe plerocercoid sues of the fish host causing adhesions, infestations. hemorrhaging (particularly the liver) and ascitic fluid resulting in abdominal dis- VII. -

Fish Tapeworm.Pmd

August 2005 Agdex 485/655-11 Fish Tapeworm in Man Many parasites infect fish, but only a few such as the broad tapeworm, Diphyllobothrium spp., occasionally infect How common is the fish man. The larval stage of these parasites develops in fish while the adults develop in various fish-eating mammals, tapeworm? marine mammals or fish-eating birds. Infections are mainly confined to regions where fish is eaten raw, marinated or undercooked. The parasite can be The best known species in this group, D. latum, is the common in some communities in Alaska and Canada, and longest tapeworm in man, reaching a length of 10 meters. rare or absent in others. This parasite is found worldwide and is common in countries where raw or undercooked fish is eaten. Several species of Diphyllobothrium occur in fish. The species most likely to infect people of a particular region will depend on the fish they consume. Diphyllobothrium latum occur in pike, walleye and perch; Diphyllobothrium Life cycle dendriticum occur primarily in whitefish and salmonids, The life cycle of the D. latum tapeworm consists of three including arctic char and trout. obligatory hosts: a mammal, a copepod and a fish (Figure 1). • The adult tapeworm attaches to the This parasite Can I see the larvae in small intestine of man, matures and sheds eggs that pass in the feces. is found fish? • The egg continues its development in D. latum is not easily seen in fish because water, eventually producing a ciliated worldwide the plerocercoids lie unencysted in fish embryo, called a coracidium, which muscle. -

Occurrence and Spatial Distribution of Dibothriocephalus Latus (Cestoda: Diphyllobothriidea) in Lake Iseo (Northern Italy): an Update

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Occurrence and Spatial Distribution of Dibothriocephalus Latus (Cestoda: Diphyllobothriidea) in Lake Iseo (Northern Italy): An Update Vasco Menconi 1 , Paolo Pastorino 1,2,* , Ivana Momo 3, Davide Mugetti 1, Maria Cristina Bona 1, Sara Levetti 1, Mattia Tomasoni 1, Elisabetta Pizzul 2 , Giuseppe Ru 1 , Alessandro Dondo 1 and Marino Prearo 1 1 The Veterinary Medical Research Institute for Piemonte, Liguria and Valle d’Aosta, 10154 Torino, Italy; [email protected] (V.M.); [email protected] (D.M.); [email protected] (M.C.B.); [email protected] (S.L.); [email protected] (M.T.); [email protected] (G.R.); [email protected] (A.D.); [email protected] (M.P.) 2 Department of Life Sciences, University of Trieste, 34127 Trieste, Italy; [email protected] 3 Department of Veterinary Sciences, University of Torino, 10095 Grugliasco, TO, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +390112686251 Received: 11 June 2020; Accepted: 12 July 2020; Published: 14 July 2020 Abstract: Dibothriocephalus latus (Linnaeus, 1758) (Cestoda: Diphyllobothriidea; syn. Diphyllobothrium latum), is a fish-borne zoonotic parasite responsible for diphyllobothriasis in humans. Although D. latus has long been studied, many aspects of its epidemiology and distribution remain unknown. The aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence, mean intensity of infestation, and mean abundance of plerocercoid larvae of D. latus in European perch (Perca fluviatilis) and its spatial distribution in three commercial fishing areas in Lake Iseo (Northern Italy). A total of 598 specimens of P. -

Thirty-Seven Human Cases of Sparganosis from Ethiopia and South Sudan Caused by Spirometra Spp

Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg., 93(2), 2015, pp. 350–355 doi:10.4269/ajtmh.15-0236 Copyright © 2015 by The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene Case Report: Thirty-Seven Human Cases of Sparganosis from Ethiopia and South Sudan Caused by Spirometra Spp. Mark L. Eberhard,* Elizabeth A. Thiele, Gole E. Yembo, Makoy S. Yibi, Vitaliano A. Cama, and Ernesto Ruiz-Tiben Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia; Ethiopia Dracunculiasis Eradication Program, Federal Ministry of Health, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; South Sudan Guinea Worm Eradication Program, Ministry of Health, Juba, Republic of South Sudan; The Carter Center, Atlanta, Georgia Abstract. Thirty-seven unusual specimens, three from Ethiopia and 34 from South Sudan, were submitted since 2012 for further identification by the Ethiopian Dracunculiasis Eradication Program (EDEP) and the South Sudan Guinea Worm Eradication Program (SSGWEP), respectively. Although the majority of specimens emerged from sores or breaks in the skin, there was concern that they did not represent bona fide cases of Dracunculus medinensis and that they needed detailed examination and identification as provided by the World Health Organization Collaborating Center (WHO CC) at Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). All 37 specimens were identified on microscopic study as larval tapeworms of the spargana type, and DNA sequence analysis of seven confirmed the identification of Spirometra sp. Age of cases ranged between 7 and 70 years (mean 25 years); 21 (57%) patients were male and 16 were female. The presence of spargana in open skin lesions is somewhat atypical, but does confirm the fact that populations living in these remote areas are either ingesting infected copepods in unsafe drinking water or, more likely, eating poorly cooked paratenic hosts harboring the parasite. -

Psychiatric Manifestations Ofneurocysticercosis: a Study of 38

61261ournal ofNeurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 1997;62:612-616 Psychiatric manifestations of neurocysticercosis: J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.62.6.612 on 1 June 1997. Downloaded from a study of 38 patients from a neurology clinic in Brazil Orestes Vicente Forlenza, Antonio Helio Guerra Vieira Filho, Jose Paulo Smith Nobrega, Luis dos Ramos Machado, Nelio Garcia de Barros, Candida Helena Pires de Camargo, Maria Fernanda Gouveia da Silva Abstract developing countries of Asia, Africa, Latin Objective-To determine the frequency America, and central Europe, where prevalence and features of psychiatric morbidity in a rates vary from 0-1 to 4-0%.2 8 It may also be cross section of 38 outpatients with neuro- found in urban areas of developed countries cysticercosis. among ethnic subgroups.9 12 Methods-Diagnosis of neurocysticerco- The two host life cycle of the cestode sis was established by CT, MRI, and CSF involves humans as definitive hosts and swine analysis. Psychiatric diagnoses were as intermediate hosts. The adult intestinal form made by using the present state examina- of the parasite is acquired by eating under- tion and the schedule for affective disor- cooked pork contaminated with cysticerci,13 14 ders and schizophrenia-lifetime version; whereas cysticercosis is usually acquired by a cognitive state was assessed by mini men- fecal-oral mechanism-that is, by the ingestion tal state examination and Strub and of Taenia solium eggs shed in the faeces of a Black's mental status examination. human carrier. Contaminated water and food Results-Signs of psychiatric disease and (especially raw vegetables) are the most com- cognitive decline were found in 65-8 and mon sources of infection.19 16 The digested eggs 87-5% of the cases respectively.