Government of Peace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NRC Publication Completes One Year

82 years of service to the nation LATE CITY PUBLISHED SIMULTANEOUSLY FROM GUWAHATI & DIBRUGARH RN-1127/57 TECH/GH – 103/2018-2020, VOL. 82, NO. 237 www.assamtribune.com Pages 12 Price: 6.00 GUWAHATI, MONDAY, AUGUST 31, 2020 p2 Hamas insists on ending p5 KVIC focuses on promotion p7 Drugs worth Rs 3.50 cr Israeli blockade on Gaza of honey industry in NE seized in Mizoram Delimitation 4-day Assembly Commission COVID deaths session from today members to GUWAHATI, Aug 30: Seven more COVID-19 Four more MLAs test COVID-19 positive visit NE soon patients – Bidyadeep SPL CORRESPONDENT Bhuyan and Kiran Bora of STAFF REPORTER carried out at the Assembly premises and Golaghat, Nipjyoti Baruah nine persons, including Haflong MLA Bir NEW DELHI, Aug 30: and Md Sohrabuddin GUWAHATI, Aug 30: Amid the COV- Bhadra Hagjer and a couple of journalists The Delimitation Commis- Ahmed of Kamrup Metro, ID-19 pandemic, a four-day autumn ses- and staff of the Assembly were found posi- sion is all set to redraw the Ramila Sutradhar and sion of the Assam Legislative Assem- tive. On Friday, five persons who were test- Lok Sabha and Assembly Sachin Chandra Brahma of bly will begin from Monday. ed along with 100 others were found posi- Chirang and Bhaskar Bijoy constituencies of Assam, For the third consecutive day on Sunday, tive. Over 25 legislators have tested posi- Gupta of Cachar – died Manipur, Nagaland and Aru- today. The toll has COVID-19 tests were carried out for legis- tive for the virus so far. nachal Pradesh besides Jam- reached 296. -

Annual Review of State Laws 2020

ANNUAL REVIEW OF STATE LAWS 2020 Anoop Ramakrishnan N R Akhil June 2021 The Constitution of India provides for a legislature in each State and entrusts it with the responsibility to make laws for the state. They make laws related to subjects in the State List and the Concurrent List of the Seventh Schedule to the Constitution. These include subjects such as agriculture, health, education, and police. At present, there are 30 state legislatures in the country, including in the two union territories of Delhi and Puducherry. State legislatures also determine the allocation of resources through their budgetary process. They collectively spend about 70% more than the centre. This implies that much of what affects citizens on a regular basis is decided at the level of the state. For a detailed discussion on the budgets of all states, please see our annual State of State Finances report. This report focuses on the legislative work performed by states in the calendar year 2020. It is based on data compiled from state legislature websites and state gazettes. It covers 19 state legislatures, including the union territory of Delhi, which together account for 90% of the population of the country. Information and data on state legislatures is not easily available. While some state legislatures publish data on a regular basis, many do not have a systematic way of reporting legislative proceedings and business. The following abbreviations are used for the state assemblies in the charts throughout the report. State Abbreviation State Abbreviation State -

35 Chapter 2 INTER-ETHNIC CONFLICTS in NORTH EAST

Chapter 2 INTER-ETHNIC CONFLICTS IN NORTH EAST INDIA India as a whole has about 4,635 communities comprising 2,000 to 3,000 caste groups, about 60,000 of synonyms of titles and sub-groups and near about 40,000 endogenous divisions (Singh 1992: 14-15). These ethnic groups are formed on the basis of religion (Hindu, Muslim, Sikh, Christian, Jain, Buddhist, etc.), sect (Nirankari, Namdhari and Amritdhari Sikhs, Shia and Sunni Muslims, Vaishnavite, Lingayat and Shaivite Hindus, etc.), language (Assamese, Bengali, Manipuri, Hindu, etc.), race (Mongoloid, Caucasoid, Negrito, etc.), caste (scheduled tribes, scheduled castes, etc.), tribe (Naga, Mizo, Bodo, Mishing, Deori, Karbi, etc.) and others groups based on national minority, national origin, common historical experience, boundary, region, sub-culture, symbols, tradition, creed, rituals, dress, diet, or some combination of these factors which may form an ethnic group or identity (Hutnik 1991; Rastogi 1986, 1993). These identities based on religion, race, tribe, language etc characterizes the demographic pattern of Northeast India. Northeast India has 4,55,87,982 inhabitants as per the Census 2011. The communities of India listed by the „People of India‟ project in 1990 are 5,633 including 635 tribal groups, out of which as many as 213 tribal groups and surprisingly, 400 different dialects are found in Northeast India. Besides, many non- tribal groups are living particularly in plain areas and the ethnic groups are formed in terms of religion, caste, sects, language, etc. (Shivananda 2011:13-14). According to the Census 2011, 45587982 persons inhabit Northeast India, out of which as much as 31169272 people (68.37%) are living in Assam, constituting mostly the non-tribal population. -

Social Change and Development

Vol. XVI No.1, 2019 Social Change and Development Social Change and Development A JOURNAL OF OKD INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL CHANGE AND DEVELOPMENT Vol. XVI No.1 January 2019 CONTENTS Editorial Note i Articles Citizens of the World but Non-Citizens of the State: The Curious Case of Stateless People with Reference to International Refugee Law Kajori Bhatnagar 1-15 The Paradox of Autonomy in the Darjeeling Hills: A Perception Based Analysis on Autonomy Aspirations Biswanath Saha, Gorky Chakraborty 16-32 BJP and Coalition Politics: Strategic Alliances in the States of Northeast Shubhrajeet Konwer 33-50 A Study of Sub-National Finance with Reference to Mizoram State in Northeast Vanlalchhawna 51-72 MGNREGS in North Eastern States of India: An Efficiency Analysis Using Data Envelopment Analysis Pritam Bose, Indraneel Bhowmik 73-89 Tribal Politics in Assam: From line system to language problem Juri Baruah 90-100 A Situational Analysis of Multidimensional Poverty for the North Eastern States of India using Household Level Data Niranjan Debnath, Salim Shah 101-129 Swachh Vidyalaya Abhiyan: Findings from an Empirical Analysis Monjit Borthakur, Joydeep Baruah 130-144 Book Review Monastic Order: An Alternate State Regime Anisha Bordoloi 145-149 ©OKDISCD 153 Social Change and Development Vol. XVI No.1, 2019 Editorial Note For long, discussions on India’s North East seem to have revolved around three issues viz. immigration, autonomy and economic underdevelopment. Though a considerable body of literature tend to deal with the three issues separately, yet innate interconnections among them are also acknowledged and often discussed. The region has received streams of immigrants since colonial times. -

The Journal of Parliamentary Information ______VOLUME LXVII NO.1 MARCH 2021 ______

The Journal of Parliamentary Information ________________________________________________________ VOLUME LXVII NO.1 MARCH 2021 ________________________________________________________ LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI ___________________________________ THE JOURNAL OF PARLIAMENTARY INFORMATION VOLUME LXVII NO.1 MARCH 2021 CONTENTS ADDRESSES PAGE Address on 'BRICS Partnership in the Interest of Global Stability, General 1 Safety and Innovative Growth: Parliamentary Dimension' at the Sixth BRICS Parliamentary Forum by the Speaker, Lok Sabha on 27 October 2020 Addresses of High Dignitaries at the 80th All India Presiding Officers' Conference, 4 Kevadia, Gujarat on 25-26 November 2020 Address Delivered by the Speaker, Lok Sabha, Shri Om Birla 5 Address Delivered by the Vice-President, Shri M. Venkaiah Naidu 7 Address Delivered by the President, Shri Ram Nath Kovind 13 Address Delivered by the Prime Minister, Shri Narendra Modi 18 Function for Laying the Foundation Stone for New Parliament Building in New 25 Delhi on 10 December 2020 Address Delivered by the Prime Minister, Shri Narendra Modi 25 Message from the President, Shri Ram Nath Kovind 32 Message from the Vice-President, Shri M. Venkaiah Naidu 33 SHORT NOTES A New Parliament for New India 34 PARLIAMENTARY EVENTS AND ACTIVITIES 39 Conferences and Symposia 39 Birth Anniversaries of National Leaders 41 Parliamentary Research & Training Institute for Democracies (PRIDE) 43 Members’ Reference Service 46 PARLIAMENTARY AND CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENTS 47 SESSIONAL REVIEW 57 State Legislatures 57 RECENT LITERATURE OF PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST 58 APPENDICES I. Statement showing the work transacted by the committees of Lok Sabha 62 during 1 October to 31 December 2020 II. Statement showing the work transacted by the committees of Rajya Sabha 64 during 1 October to 31 December 2020 III. -

DETAILS Revenue Account ৰাজহ ন তান PART

GRANT NO. 38-WELFARE OF SC/ST & OBC ভঞ্জৰু ী নং ৩৮ - অনুসুনচত জানত, জন-জানত আৰু অনযানয নছৰা শ্ৰেণীৰ কলযান I-Estimate of the amount required for the year ending 31st March,2021 to defray the expenses in connection with the Administration of "Welfare of SC/ST & OBC" ২০২১ চনৰ ৩১ ভাচ্ ত শ্ৰ ষ হ`ফলগীয়া ফছৰশ াত "অনুসনূ চত জানত, অনুসনূ চত জনজানত আৰু অনযানয নছৰা শ্ৰেণীৰ কলযাণ"ৰ শ্ৰেত্ৰত ফহন কনৰফলগীয়া ফযয়ৰ আনুভাননক নহচা REVENUE CAPITAL TOTAL (Rs.in Lakhs) ৰাজহ ভুলধন ভুঠ লাখ কাৰ নহচাত Voted 162320.30 8501.11 170821.41 গহৃ ীত Charged 0.00 0.00 0.00 ধাম্য II-The heads under which this grant will be accounted for by the "Tribes Administration & Welfare of Backward Classes Department" ভবয়াভ জনজানত আৰু নছৰা শ্ৰেণীৰ কলযাণ নফবাগৰ িাৰা ননয়নিত এই ধন নহচাৰ উ- ন তানসভহূ । Budget Revised Budget Actual 2018-19 Estimates 2019- Estimates 2019- Estimates 2020- 20 20 21 Head of Account সংশ ানধত ফযয়ৰ নহচাৰ ন তান ফযয়ৰ ফযয়ৰ প্ৰকৃ ত ফযয় আনুভাননক আনুভাননক অনুভাননক নহচা নহচা নহচা [1] [3] [4] [5] [6] PART - I - DETAILS প্ৰথভ খণ্ডৰ নফ দ নফৱৰণ Welfare of Scheduled Caste, Scheduled 73363.24 114898.19 138894.70 2225 162320.30 Tribes অনুসুনচত জানত, অনুসুনচত জন-জানত আৰু অনযানয নছৰা শ্ৰেণীৰ কলযান Capital Outlay on Welfare of Scheduled 1028.22 14174.60 14524.61 4225 Castes, Scheduled tribes and Other 8501.11 Backward Classes অনুসুনচত জানত, অনুসুনচত জন-জানত আৰু অনযানয নছৰা শ্ৰেণীৰ কলযান 74391.46 129072.79 153419.31 Grand Total 170821.41 PART - II - DETAILS নিতীয় খণ্ডৰ নফ দ নফৱৰণ Revenue Account ৰাজহ ন তান B. -

Search for Peace with Justice: Issues Around Conflicts in Northeast India Search for Peace with Justice: © North Eastern Social Research Centre, Guwahati, 2008

Search for Peace with Justice: Issues Around Conflicts in Northeast India Search for Peace with Justice: © North Eastern Social Research Centre, Guwahati, 2008. Issues Around Conflicts in Published by Northeast India North Eastern Social Research Centre 110 Kharghuli Road (1st floor) Guwahati 781004 Assam, India Telephone: (0361) 2602819 Fax: (0361) 2732629 (Attn NESRC) Email: [email protected] Editor Walter Fernandes Website: www.creighton.edu/CollaborativeMinistry/NESRC Cover Design: Kazimuddin Ahmed Panos Southasia 110 Kharghuli Road (1st floor) Guwahati 781004 Assam, India North Eastern Social Research Centre Printed by: Saraighat Laser Print Guwahati Silpukhuri 2008 Guwahati-3 About the Authors Acknowledgements Dr Walter Fernandes is Director, North Eastern Social Research Centre, Guwahati. Email: [email protected] With a sense of gratitude I present this book to the public of Prof. M. N. Karna former Professor and Head, Department of Sociology, the Northeast as a tribute to all those who are involved in peace North Eastern Hill University is at present with the Department of initiatives and struggles for justice in the region. It is an outcome Sociology, Tezpur University, Assam. Email: [email protected] of several seminars and discussion sessions organised as part of the peace initiatives programme of North Eastern Social Research Dr Nani Gopal Mahanta is Reader, Department of Political Science and Centre (NESRC). The programme as well as this book were Coordinator, Peace and Conflict Studies, Gauhati University. Email: sponsored by CRS, Guwahati. In the name of all the authors and [email protected] participants at the seminars I thank CRS, particularly Enakshi Dutta Ms Rita Manchanda works with the South Asian Forum for Human and Mangneo Lungdhim for this support. -

(Amendment) Bill, 2020 Passed Assembly Passes Bill to Provide Relief to MSME Sector

CIVIL SERVICES ACHIEVERS' POINT, GUWAHATI THE ASSAM TRIBUNE ANALYSIS Date - 04 September 2020 (For Preliminary and Mains Examination) As per New Pattern of APSC (Also useful for UPSC and other State Level Government Examinations) Join our Regular/Online Classes. For details contact 8811877068 CIVIL SERVICES ACHIEVERS' POINT, GUWAHATI CONTENTS State to get 3 more autonomous councils - Moran, Matak, Kamatapur Kaziranga set to grow bigger by 31 sq km Capital Region Devp Authority (Amendment) Bill passed Assam Inland Water Transport Regulatory Authority (Amendment) Bill, 2020 passed Assembly passes Bill to provide relief to MSME sector Join our Regular/Online Classes. For details contact 8811877068 CIVIL SERVICES ACHIEVERS' POINT, GUWAHATI EDITORIAL o 15th Finance Commission’s awards o For a healthy competition culture o Heritage sites Join our Regular/Online Classes. For details contact 8811877068 CIVIL SERVICES ACHIEVERS' POINT, GUWAHATI State to get 3 more autonomous councils – Moran, Matak, Kamatapur (General Studies on Assam: Polity, Governance) oThe Assam Legislative Assembly paved the way for formation of three new autonomous councils in the State by passing the Moran Autonomous Council Bill, 2020, the Matak Autonomous Council Bill, 2020 and the Kamatapur Autonomous Council Bill, 2020. oThe three Bills were moved in the State Assembly by Minister for Welfare of Plain Tribes and Backward Classes Chandan Brahma. oThe minister said that the Kamatapur Autonomous Council will have its territory in the undivided Goalpara district, excluding the BTAD and the Rabha Hasong Autonomous Council areas. Join our Regular/Online Classes. For details contact 8811877068 CIVIL SERVICES ACHIEVERS' POINT, GUWAHATI oThe Moran Autonomous Council and Matak Autonomous Council will have their territories demarcated in the upper Assam region. -

Internal Displacement, Migration, and Policy in Northeastern India

No. 8, April 2007 InternalȱDisplacement,ȱ Migration,ȱandȱPolicyȱinȱ PAPERS ȱ NortheasternȱIndia Uddipana Goswami East-West Center Washington WORKING EastȬWestȱCenterȱ TheȱEastȬWestȱCenterȱisȱanȱ internationallyȱrecognizedȱeducationȱ andȱresearchȱorganizationȱ establishedȱbyȱtheȱU.S.ȱCongressȱinȱ 1960ȱtoȱstrengthenȱunderstandingȱ andȱrelationsȱbetweenȱtheȱUnitedȱ StatesȱandȱtheȱcountriesȱofȱtheȱAsiaȱ Pacific.ȱThroughȱitsȱprogramsȱofȱ cooperativeȱstudy,ȱtraining,ȱ seminars,ȱandȱresearch,ȱtheȱCenterȱ worksȱtoȱpromoteȱaȱstable,ȱpeacefulȱ andȱprosperousȱAsiaȱPacificȱ communityȱinȱwhichȱtheȱUnitedȱ Statesȱisȱaȱleadingȱandȱvaluedȱ partner.ȱFundingȱforȱtheȱCenterȱ comesȱforȱtheȱU.S.ȱgovernment,ȱ privateȱfoundations,ȱindividuals,ȱ corporationsȱandȱaȱnumberȱofȱAsiaȬ Pacificȱgovernments.ȱȱ EastȬWestȱCenterȱWashington EstablishedȱonȱSeptemberȱ1,ȱ2001,ȱtheȱ primaryȱfunctionȱofȱtheȱEastȬWestȱ CenterȱWashingtonȱisȱtoȱfurtherȱtheȱ EastȬWestȱCenterȱmissionȱandȱtheȱ institutionalȱobjectiveȱofȱbuildingȱaȱ peacefulȱandȱprosperousȱAsiaȱPacificȱ communityȱthroughȱsubstantiveȱ programmingȱactivitiesȱfocusedȱonȱ theȱthemeȱofȱconflictȱreductionȱinȱtheȱ AsiaȱPacificȱregionȱandȱpromotingȱ Americanȱunderstandingȱofȱandȱ engagementȱinȱAsiaȱPacificȱaffairs. ContactȱInformation: Editor,ȱEWCWȱWorkingȱPapers EastȬWestȱCenterȱWashington 1819ȱLȱStreet,ȱNW,ȱSuiteȱ200 Washington,ȱD.C.ȱȱ20036 Tel:ȱ(202)ȱ293Ȭ3995 Fax:ȱ(202)ȱ293Ȭ1402 [email protected] Uddipana Goswamiȱis a Ph.D. fellow at the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta (CSSSCAL). EastȬWestȱCenterȱWashingtonȱWorkingȱPapers -

Volume X – 1 Summer 2018

i CONTEMPORARY SOCIAL SCIENTIST (A National Refereed Journal) Vol :X-1 Summer 2018 ISSN No: 2230 - 956X SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES, MIZORAM UNIVERSITY (A Central University) TANHRIL, AIZAWL – 796004 MIZORAM, INDIA ii iii CONTEMPORARY SOCIAL SCIENTIST (A National Refereed Journal) Vol :X-1 Summer 2018 ISSN No: 2230 - 956X Prof. Zokaitluangi Editor in Chief Dean, School of Social Sciences, Mizoram University & Professor, Department of Psychology, MZU SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES MIZORAM UNIVERSITY (A CENTRAL UNIVERSITY) TANHRIL, AIZAWL – 796004 MIZORAM, INDIA e-mail : [email protected] iv v CONTEMPORARY SOCIAL SCIENTIST (A National Refereed Journal) Vol :X-1 Summer 2018 ISSN No: 2230 - 956X School of Social Editors Sciences- Convergence Editors Patron: Vice Chancellor, Mizoram University, Aizawl, India Guidelines Editor in Chief: Professor Zokaitluangi, Dean , Shool of Social Sciences, Mizoram University, Aizawl, India Archives (hard copy) Editorial boards: Prof. J.K. PatnaikDepartment of Political Science, MZU Prof. Srinibas Pathi, Head Department of Public Administration, MZU Vol: I - 1 Prof. O. Rosanga, Department of History & Ethnography, MZU Vol: I - 2 Prof. Lalrintluanga, Department of Public Administration, MZU Vol: II - 1 Prof. Lalneihzovi, Department of Public Admn, MZU Vol: II - 2 Prof. C. Lalfamkima Varte, Head, Dept. of Psychology, MZU Vol: III - 1 Prof. H.K. Laldinpuii Fente, Department of Psychology, MZU Vol: III - 2 Prof. E. Kanagaraj, Department. of Social Work, MZU Vol: IV - 1 Prof. J. Doungel, Department of Political Science, MZU Vol: IV - 2 Prof. C. Devendiran, Head, Department of Social Work, MZU Vol: V - 1 Vol: V - 2 Prof. K.V. Reddy, Head, Department of Political Science, MZU Vol: VI - 1 Dr. -

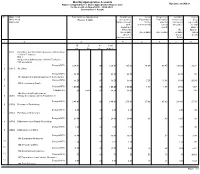

Monthly Appropriation Accounts

Monthly Appropriation Accounts Run Date: 28-JAN-21 Report on Expenditure of Grant /Appropriation-Head of State for the month of August'2020 - (2020-2021) Government of Assam No Major Head Total Grant or Appropriation Available(+)/ Actual Progressive Available %age of Minor Head (Rupees in lakh) over spent(-) Expenditure Expenditure balance(+) prog. Sub Head balance amount for the upto the over spent exp.(col.6) at the current month current amount(-) to total begining of month garnt or the month (Rs. Approp- (Rs. in lakh) (Rs. in lakh) (Rs. in lakh) in lakh) riation (Col.7 of (Col.3- (Col.3) previous month) Col.6) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 OSR Total (a) (b) (c) (a+b+c) 2012 President, Vice President/ Governor, Administrator of Union Territories NULL 03 Governor/Administrator of Union Territories 090 Secretariat 1 Charged NTA 3,36.81 .00 3,36.81 2,85.30 16.94 68.45 2,68.36 20.32 2 {5344} Air Lifting Charged NTA 88.00 .00 88.00 88.00 88.00 .00 101 Emoluments and Allowances of the Governor 3 Charged NTA 45.29 .00 45.29 35.54 2.20 11.95 33.34 26.39 102 Discretionary Grants 4 Charged NTA 1,00.00 .00 1,00.00 1,00.00 1.67 1.67 98.33 1.67 Charged TA .30 14.00 .00 14.30 14.30 14.30 .00 103 Household Establishment 5 {0301} Military Secretariat and his Establishment Charged NTA 3,44.93 .00 3,44.93 2,76.91 27.80 95.82 2,49.11 27.78 6 {2003} Renewal of Furnishings Charged NTA 6.00 .00 6.00 6.00 6.00 .00 7 {2042} Purchase of Motor Cars Charged NTA 20.00 .00 20.00 20.00 .03 .03 19.97 .16 8 {3003} Maintenance and Repair Furnishings Charged NTA 2.00 .00 2.00 2.00 -

Annual Reports of NHIDCL (7.79 Mb )

Index Sl.No. Contents Page No. I Introduction 1 II Vision, Mission, Core Strategies and Values. 2 III Organization chart 3 IV Profile of the Board of Directors 4-5 V Chairman’s Address 6 VI Message of Managing Director 7 VII Message of the Director (A&F) 8 Administration i. Location VIII 9-11 ii. Branch offices iii. Staff strength IX Important Events during 2016-17 12-15 X Physical Performance during 2016-17 16-17 XI Status of Projects as on 31.03.2017 and Future Prospects 18-57 XII Notice for convening Third AGM 58-59 XIII Directors report & Annexure 60-81 Report of the Statutory Auditor on the Financial statement of XIV 82-91 2016-17 XV Financial Performance 2016-17 92-104 Glimpses of some important events through the photographer’s XVI 105-117 lens Annual Report 2016-17 Introduction The National Highways and Infrastructure Development Corporation Limited (NHIDCL) was incorporated on 18th July, 2014 as a Public Sector Undertaking under the Companies Act, 2013, under the Ministry of Road Transport & Highways, Government of India, inter alia, work approved share capital of Rs. 100 crores and paid up capital of Rs. 5 lakhs with an objective to fast pace construction of National Highways and other infrastructure in the North Eastern Region and Strategic Areas of the country which share international boundaries. The effort is aimed at economically consolidating these areas with overall economic benefits flowing to the local population while integrating them in more robust manner with the mainstream. The company started its effective functioning on 22nd Sep.