Was L. Ron Hubbard Drugged out When He Developed OT III?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Miscavige Legal Statements: a Study in Perjury, Lies and Misdirection

SPEAKING OUT ABOUT ORGANIZED SCIENTOLOGY ~ The Collected Works of L. H. Brennan ~ Volume 1 The Miscavige Legal Statements: A Study in Perjury, Lies and Misdirection Written by Larry Brennan [Edited & Compiled by Anonymous w/ <3] Originally posted on: Operation Clambake Message board WhyWeProtest.net Activism Forum The Ex-scientologist Forum 2006 - 2009 Page 1 of 76 Table of Contents Preface: The Real Power in Scientology - Miscavige's Lies ...................................................... 3 Introduction to Scientology COB Public Record Analysis....................................................... 12 David Miscavige’s Statement #1 .............................................................................................. 14 David Miscavige’s Statement #2 .............................................................................................. 16 David Miscavige’s Statement #3 .............................................................................................. 20 David Miscavige’s Statement #4 .............................................................................................. 21 David Miscavige’s Statement #5 .............................................................................................. 24 David Miscavige’s Statement #6 .............................................................................................. 27 David Miscavige’s Statement #7 .............................................................................................. 29 David Miscavige’s Statement #8 ............................................................................................. -

HUBBARD COMMUNICATIONS OFFICE Saint Hill Manor, East Grinstead, Sussex

HUBBARD COMMUNICATIONS OFFICE Saint Hill Manor, East Grinstead, Sussex HCO POLICY LETTER OF 29 JUNE 1961 CenOCon STUDENT SECURITY CHECK (HCO WW Sec Form 5) This is a Processing or a Security Check. As a Processing Check it is given in Model Session. The following Security Check is the only student security check (in addition to the standard Joburg and HCO WW Sec Form 6) to be used in Academies and courses. HCO WW SEC FORM 5 SCIENTOLOGY STUDENTS’ SECURITY CHECK (For Academies, ACCs, etc.) The first few questions below are for a student who has registered, but has not yet started on course, and who has never had a course in Scientology or Dianetics. The whole battery is given to a student actually on course, or who has had a previous course in Scientology, or Dianetics. Has anyone given, or loaned, you money to help cover your tuition, or expenses, while on this course? If so: Have you promised them something in return for this? If so: What exactly have you committed yourself to? If so: Do you intend to make good this obligation? Are you coming on this course in order to get away from someone, or something? Do you have any goal for being on this course which, if achieved, would result in harm to another person, his possessions, or his reputation? Are you here in order to get into anything? Have you promised anyone auditing which you do not intend to give? Have you read, or had read to you, the course Rules and Regulations? If so: Are there any which you do not intend to comply with? Are you here to find out whether Scientology works? Are -

Going Clear: Scientology and the Prison of Belief Discussion Guide

www.influencefilmclub.com Going Clear: Scientology and the Prison of Belief Discussion Guide Director: Alex Gibney Year: 2015 Time: 119 min You might know this director from: Sinatra: All or Nothing at All (2015) Steve Jobs: Man in the Machine (2015) Mr. Dynamite: The Rise of James Brown (2014) The Armstrong Lie (2013) We Steal Secrets: The Story of WikiLeaks (2013) The Last Gladiators (2011) My Trip to Al-Qaeda (2010) Taxi to the Dark Side (2007) Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room (2005) FILM SUMMARY “My conclusions were that man was a spiritual being that was pulled down to the material, the fleshy interests, to an interplay in life that was in fact too great for him to control. I concluded finally that he needed a hand,” stated Scientology founding father L. Ron Hubbard. That helping hand became a clenching fist around the throat of many a devout member, which director Alex Gibney reveals in his investigation behind the curtain of Scientology. Having read “Going Clear: Scientology, Hollywood, and the Prison of Belief” by Lawrence Wright, Gibney signed up to create a film for HBO on the mysterious religion, addressing the numerous allegations of human rights abuses for which it was under attack. With Gibney’s track record of probing power abuse in its many forms, the disputable practices of Hubbard and his enigmatic successor David Miscavige made for prime material. A number of credible ex-members are interviewed, including filmmaker Paul Haggis and John Travolta’s former representative Spanky Taylor, and their journeys up “The Bridge” of Scientology and subsequent rejection of the organization that had promised them spiritual freedom - along with with a hefty financial and personal price tag- serve as the film’s focal point. -

Scientology: CRIMINAL TIME TRACK ISSUE I by Mike Mcclaughry 1999

Scientology: CRIMINAL TIME TRACK ISSUE I by Mike McClaughry 1999 The following is a Time Track that I put together for myself and some friends at the time, in 1999. I originally used the pseudonym “Theta” at the request of Greg Barnes until he was ready to “go public” with his defection from Scientology. I also used the pseudonym “Theta 8-8008” around this same time period. Bernd Luebeck, Ex-Guardian’s Office Intelligence and then Ron’s Org staff ran the website www.freezone.org. In 1999, just after my time track was released privately, Bernd used it on his website as-is. He later expanded on my original time track with items of interest to himself. Prior to my doing this time track, Bernd, (nor anyone else involved with Scientology on the internet), had ever thought of the idea to do things this way in relation to Scientology. Mike McClaughry BEGIN An open letter to all Scientologists: Greetings and by way of introduction, I am a Class 8, OT 8, who has been in the Church for many decades and I am in good standing with the Church. I am a lover of LRH’s technology and that is my motivation in writing you and in doing what I am now doing. It came to my attention, sometime in the not too distant past, that the current top management of the Church, particularly David Miscavige, is off source. One of the ways he is off-source is that he has made the same mistake as the old Guardian’s Office staff made, engaging in criminal activities to solve problems. -

L. Ron Hubbard FOUNDER of DIANETICS and SCIENTOLOGY Volume POWER & SOLO

The Technical Bulletins of Dianetics and Scientology by L. Ron Hubbard FOUNDER OF DIANETICS AND SCIENTOLOGY Volume POWER & SOLO CONFIDENTIAL Contents Power Power Processes 19 Power Badges 20 Power Processes 21 Six Power Processes 22 The Standard Flight To Power & VA 23 Gain The Ability To Handle Power 25 The Power Processes 26 Power Process 1AA (Pr Pr 1AA) 32 Power Process 1 (Pr Pr 1) 32 Power Process 2 (Pr Pr 2) 32 Power Process 3 (Pr Pr 3) 32 Power Process 4 (Pr Pr 4) 32 Power Process 5 (Pr Pr 5) 33 Power Process 6 (Pr Pr 6) 33 The Power Processes All Flows 34 Data On Pr Prs 37 End Phenomena And F/ Ns In Power 38 L P - 1 40 Low TA Cases 41 Power Plus 43 Restoring The Knowledge You Used To Have 45 Power Plus Release - 5A Processes 46 Power Plus Processes All Flows 47 Rehab Of VA 48 GPM Research Material 51 Editors Note 53 Routine 3 54 Current Auditing 59 Routine 3M Rundown By Steps 61 Correction To HCO Bulletin Of February 22, 1963 66 R3M Goal Finding By Method B 67 Routine 2 And 3M Correction To 3M Steps 13, 14 68 Vanished RS Or RR 71 The End Of A GPM 74 R2- R3 Corrections Typographicals And Added Notes 79 Routine 3M Simplified 80 R3M2 What You Are Trying To Do In Clearing 89 Routine 3M2 Listing And Nulling 92 Routine 3M2 Corrected Line Plots 96 R3M2 Redo Goals On This Pattern 103 Routine 3M2 Directive Listing 107 Routine 3M2 Handling The GPM 109 Routine 3M2 Tips - The Rocket Read Of A Reliable Item 113 Routine 3 An Actual Line Plot 115 7 Routine 3 Directive Listing Listing Liabilities 120 Routine 3 Correction To HCOB 23 Apr. -

Benefits I Have Received from Scientology Auditing and Train

14 August 1997 Dear I have been asked to describe certain 'secular' benefits I have received from Scientology auditing and training that are not generally understood to be religious or spiritual in nature and how these have affected my community services activities. From my own schooldays I had a purpose to help other children gain a good education and to this end became a qualified teacher and pursued this profession until I married and had a family. I then came into contact with Scientology and through it gained greater self reliance and greater confidence in handling projects Also I was trained in the use of the study method developed by L Ron Hubbard and decided that I wanted to use it to help children to study better in school. With the help of a local West Indian businessman and other volunteers I started Riving supplementary teaching in the evening to disadvantaged children in Brixton , something which was especially wanted by West Indian parents in the drea. This project which we named B.E.S.T, ( the Basic Education and Supplementary Teaching .Association ) is now an authorised charity and continues to provide supplementary teaching and vacation projects in the Brixton area. More recently I have taken on another volunteer activity, that of bringing this study method to teachers in a country in Southern Africa. The education authorities in that country had become aware that the academic results being achieved in their schools were not sufficiently being translated into success in the professions and the workplace. L Ron Hubbard's Study Technology with its emphasis on fully understanding and being able to apply the data being studied was demonstrated in a pilot project and was shown to markedly increase student interest and comprehension and to greatly reduce truancy and its introduction was approved. -

The Technical Bulletins of Dianetics and Scientology by L

The Technical Bulletins of Dianetics and Scientology by L. Ron Hubbard FOUNDER OF DIANETICS AND SCIENTOLOGY Volume VIII 1972-1976 _____________________________________________________________________ I will not always be here on guard. The stars twinkle in the Milky Way And the wind sighs for songs Across the empty fields of a planet A Galaxy away. You won’t always be here. But before you go, Whisper this to your sons And their sons — “The work was free. Keep it so.” L. RON HUBBARD L. Ron Hubbard Founder of Dianetics and Scientology EDITORS’ NOTE “A chronological study of materials is necessary for the complete training of a truly top grade expert in these lines. He can see how the subject progressed and so is able to see which are the highest levels of development. Not the least advantage in this is the defining of words and terms for each, when originally used, was defined, in most cases, with considerable exactitude, and one is not left with any misunderstoods.” —L. Ron Hubbard The first eight volumes of the Technical Bulletins of Dianetics and Scientology contain, exclusively, issues written by L. Ron Hubbard, thus providing a chronological time track of the development of Dianetics and Scientology. Volume IX, The Auditing Series, and Volume X, The Case Supervisor Series, contain Board Technical Bulletins that are part of the series. They are LRH data even though compiled or written by another. So that the time track of the subject may be studied in its entirety, all HCO Bs have been included, excluding only those upper level materials which will be found on courses to which they apply. -

Scientology in Court: a Comparative Analysis and Some Thoughts on Selected Issues in Law and Religion

DePaul Law Review Volume 47 Issue 1 Fall 1997 Article 4 Scientology in Court: A Comparative Analysis and Some Thoughts on Selected Issues in Law and Religion Paul Horwitz Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review Recommended Citation Paul Horwitz, Scientology in Court: A Comparative Analysis and Some Thoughts on Selected Issues in Law and Religion, 47 DePaul L. Rev. 85 (1997) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review/vol47/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Law Review by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SCIENTOLOGY IN COURT: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS AND SOME THOUGHTS ON SELECTED ISSUES IN LAW AND RELIGION Paul Horwitz* INTRODUCTION ................................................. 86 I. THE CHURCH OF SCIENTOLOGY ........................ 89 A . D ianetics ............................................ 89 B . Scientology .......................................... 93 C. Scientology Doctrines and Practices ................. 95 II. SCIENTOLOGY AT THE HANDS OF THE STATE: A COMPARATIVE LOOK ................................. 102 A . United States ........................................ 102 B . England ............................................. 110 C . A ustralia ............................................ 115 D . Germ any ............................................ 118 III. DEFINING RELIGION IN AN AGE OF PLURALISM -

The Technical Bulletins of Dianetics and Scientology

The Technical Bulletins of Dianetics and Scientology by L. Ron Hubbard FOUNDER OF DIANETICS AND SCIENTOLOGY Volume XIV THE O.T. LEVELS _____________________________________________________________________ I will not always be here on guard. The stars twinkle in the Milky Way And the wind sighs for songs Across the empty fields of a planet A Galaxy away. You won’t always be here. But before you go, Whisper this to your sons And their sons — “The work was free. Keep it so.” L. RON HUBBARD 2 L. RON HUBBARD Founder of Dianetics and Scientology 3 4 CONTENTS 5 Contents ORIGINAL OT 1.......................................................................................................13 OT 1 Checksheet ................................................................................................15 Clear And OT.....................................................................................................16 An Open Letter To All Clears .......................................................................17 Floating Needles ................................................................................................19 OT 1 Instructions ...............................................................................................20 OT 1 Steps..........................................................................................................22 NEW OT 1..................................................................................................................27 New OT 1 Instructions .......................................................................................29 -

2008 Annual Report Dow Jones Newspaper Fund, Inc. on the Cover Karl Grubaugh, 2008 National High School Journalism Teacher of the Year; S

2008 Annual Report Dow Jones Newspaper Fund, Inc. On the Cover Karl Grubaugh, 2008 National High School Journalism Teacher of the Year; S. Griffin Singer teaching interns at the University of Texas at Austin; Tony Ortega of The Village Voice with students from the New York University Urban Journalism Workshop. Table of Contents From the President 2 From the Executive Director 3 Programs At-A-Glance 4 2008 Financial Report 5 Programs College Programs Multimedia Internships 6 News Editing Internships 7 Sports Editing Internships 8 Business Reporting Internships 9 High School Programs Summer High School Journalism Workshops 10 High School Newspaper Project 14 Teacher Programs National High School Journalism Teacher of the Year 15 Publications 18 Board of Directors 19 Guidelines 20 The Dow Jones Newspaper Fund is a nonprofit foundation established in 1958 and supported by the Dow Jones Foundation and media companies. Its purpose is to promote careers in print and online journalism. The Dow Jones Newspaper Fund, Inc. P.O. Box 300 Princeton, New Jersey 08543-0300 Phone: (609) 452-2820 FAX: (609) 520-5804 Web: https://www.newspaperfund.org Email: [email protected] © 2009 Copyright Dow Jones Newspaper Fund, Inc. From the President/Richard J. Levine Dealing with Reality “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.” The famous opening line of Charles Dickens’ “A Tale of Two Cities” strikes me as an apt description of the year 2008 in the newspaper industry, which for the past half-century has been the key partner of the Dow Jones Newspaper Fund in developing young journalists. -

The Unbreakable Miss Lovely: How the Church of Scientology Tried to Destroy Paulette Cooper Pdf

FREE THE UNBREAKABLE MISS LOVELY: HOW THE CHURCH OF SCIENTOLOGY TRIED TO DESTROY PAULETTE COOPER PDF Tony Ortega | 406 pages | 01 May 2015 | Createspace Independent Publishing Platform | 9781511639378 | English | United States The Unbreakable Miss Lovely | Kirkus Reviews Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Ron Hubbard, back into print for the first time in 27 years. It is an extraordinary story of terrible things done to a woman who did not deserve them and shines a light into the darkest corner of the history of the Church of Scientology. Tony has done a wonderful job with the narrative — the story reads like a thriller. Silvertail bought world rights directly from the author and will publish in paperback and ebook in May in the US and the UK. Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. Published May 31st by Silvertail Books first published May 1st More Details Edition Language. Other Editions 4. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To ask other readers questions about The Unbreakable Miss Lovelyplease sign up. Be the first to ask a question about The Unbreakable The Unbreakable Miss Lovely: How the Church of Scientology Tried to Destroy Paulette Cooper Lovely. Lists with This Book. Community Reviews. Showing Average rating 4. Rating details. More filters. Sort order. A Tiger never changes its stripes! Scientology harassed and spied on me for many years well after Paulette Cooper's harassment. -

Deposition-Of-Marty-Rathbun

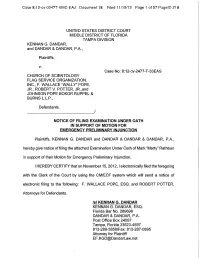

Case 8:12-cv-02477-VMC-EAJ Document 18 Filed 11/15/12 Page 1 of 57 PageID 218 Case 8:12-cv-02477-VMC-EAJ Document 18 Filed 11/15/12 Page 2 of 57 PageID 219 Case 8:12-cv-02477-VMC-EAJ Document 18 Filed 11/15/12 Page 3 of 57 PageID 220 Case 8:12-cv-02477-VMC-EAJ Document 18 Filed 11/15/12 Page 4 of 57 PageID 221 Case 8:12-cv-02477-VMC-EAJ Document 18 Filed 11/15/12 Page 5 of 57 PageID 222 Case 8:12-cv-02477-VMC-EAJ Document 18 Filed 11/15/12 Page 6 of 57 PageID 223 Case 8:12-cv-02477-VMC-EAJ Document 18 Filed 11/15/12 Page 7 of 57 PageID 224 Case 8:12-cv-02477-VMC-EAJ Document 18 Filed 11/15/12 Page 8 of 57 PageID 225 Case 8:12-cv-02477-VMC-EAJ Document 18 Filed 11/15/12 Page 9 of 57 PageID 226 Case 8:12-cv-02477-VMC-EAJ Document 18 Filed 11/15/12 Page 10 of 57 PageID 227 Case 8:12-cv-02477-VMC-EAJ Document 18 Filed 11/15/12 Page 11 of 57 PageID 228 Case 8:12-cv-02477-VMC-EAJ Document 18 Filed 11/15/12 Page 12 of 57 PageID 229 Case 8:12-cv-02477-VMC-EAJ Document 18 Filed 11/15/12 Page 13 of 57 PageID 230 Case 8:12-cv-02477-VMC-EAJ Document 18 Filed 11/15/12 Page 14 of 57 PageID 231 Case 8:12-cv-02477-VMC-EAJ Document 18 Filed 11/15/12 Page 15 of 57 PageID 232 Case 8:12-cv-02477-VMC-EAJ Document 18 Filed 11/15/12 Page 16 of 57 PageID 233 Case 8:12-cv-02477-VMC-EAJ Document 18 Filed 11/15/12 Page 17 of 57 PageID 234 Case 8:12-cv-02477-VMC-EAJ Document 18 Filed 11/15/12 Page 18 of 57 PageID 235 Case 8:12-cv-02477-VMC-EAJ Document 18 Filed 11/15/12 Page 19 of 57 PageID 236 Case 8:12-cv-02477-VMC-EAJ Document 18 Filed 11/15/12 Page 20 of 57 PageID