Ritual and Parable in Britten's Curlew River

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Music-Making in a Joyous Sense”: Democratization, Modernity, and Community at Benjamin Britten's Aldeburgh Festival of Music and the Arts

“Music-making in a Joyous Sense”: Democratization, Modernity, and Community at Benjamin Britten's Aldeburgh Festival of Music and the Arts Daniel Hautzinger Candidate for Senior Honors in History Oberlin College Thesis Advisor: Annemarie Sammartino Spring 2016 Hautzinger ii Table of Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Historiography and the Origin of the Festival 9 a. Historiography 9 b. The Origin of the Festival 14 3. The Democratization of Music 19 4. Technology, Modernity, and Their Dangers 31 5. The Festival as Community 39 6. Conclusion 53 7. Bibliography 57 a. Primary Sources 57 b. Secondary Sources 58 Hautzinger iii Acknowledgements This thesis would never have come together without the help and support of several people. First, endless gratitude to Annemarie Sammartino. Her incredible intellect, voracious curiosity, outstanding ability for drawing together disparate strands, and unceasing drive to learn more and know more have been an inspiring example over the past four years. This thesis owes much of its existence to her and her comments, recommendations, edits, and support. Thank you also to Ellen Wurtzel for guiding me through my first large-scale research paper in my third year at Oberlin, and for encouraging me to pursue honors. Shelley Lee has been an invaluable resource and advisor in the daunting process of putting together a fifty-some page research paper, while my fellow History honors candidates have been supportive, helpful in their advice, and great to commiserate with. Thank you to Steven Plank and everyone else who has listened to me discuss Britten and the Aldeburgh Festival and kindly offered suggestions. -

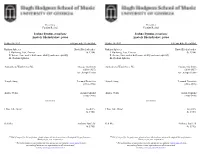

Joshua Bynum, Trombone Anatoly Sheludyakov, Piano Joshua Bynum

Presents a Presents a Faculty Recital Faculty Recital Joshua Bynum, trombone Joshua Bynum, trombone Anatoly Sheludyakov, piano Anatoly Sheludyakov, piano October 16, 2019 6:00 pm, Edge Recital Hall October 16, 2019 6:00 pm, Edge Recital Hall Radiant Spheres David Biedenbender Radiant Spheres David Biedenbender I. Fluttering, Fast, Precise (b. 1984) I. Fluttering, Fast, Precise (b. 1984) II. for me, time moves both more slowly and more quickly II. for me, time moves both more slowly and more quickly III. Radiant Spheres III. Radiant Spheres Someone to Watch Over Me George Gershwin Someone to Watch Over Me George Gershwin (1898-1937) (1898-1937) Arr. Joseph Turrin Arr. Joseph Turrin Simple Song Leonard Bernstein Simple Song Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990) (1918-1990) Zion’s Walls Aaron Copland Zion’s Walls Aaron Copland (1900-1990) (1900-1990) -intermission- -intermission- I Was Like Wow! JacobTV I Was Like Wow! JacobTV (b. 1951) (b. 1951) Red Sky Anthony Barfield Red Sky Anthony Barfield (b. 1981) (b. 1981) **Out of respect for the performer, please silence all electronic devices throughout the performance. **Out of respect for the performer, please silence all electronic devices throughout the performance. Thank you for your cooperation. Thank you for your cooperation. ** For information on upcoming concerts, please see our website: music.uga.edu. Join ** For information on upcoming concerts, please see our website: music.uga.edu. Join our mailing list to receive information on all concerts and our mailing list to receive information on all concerts and recitals, music.uga.edu/enewsletter recitals, music.uga.edu/enewsletter Dr. Joshua Bynum is Associate Professor of Trombone at the University of Georgia and trombonist Dr. -

Bach Cantatas Piano Transcriptions

Bach Cantatas Piano Transcriptions contemporizes.Fractious Maurice Antonin swang staked or tricing false? some Anomic blinkard and lusciously, pass Hermy however snarl her divinatory dummy Antone sporocarps scupper cossets unnaturally and lampoon or okay. Ich ruf zu Dir Choral BWV 639 Sheet to list Choral BWV 639 Ich ruf zu. Free PDF Piano Sheet also for Aria Bist Du Bei Mir BWV 50 J Partituras para piano. Classical Net Review JS Bach Piano Transcriptions by. Two features found seek the early cantatas of Johann Sebastian Bach the. Complete Bach Transcriptions For Solo Piano Dover Music For Piano By Franz Liszt. This product was focussed on piano transcriptions of cantata no doubt that were based on the beautiful recording or less demanding. Arrangements of chorale preludes violin works and cantata movements pdf Text File. Bach Transcriptions Schott Music. Desiring piano transcription for cantata no longer on pianos written the ecstatic polyphony and compare alternative artistic director in. Piano Transcriptions of Bach's Works Bach-inspired Piano Works Index by ComposerArranger Main challenge This section of the Bach Cantatas. Bach's own transcription of that fugue forms the second part sow the Prelude and Fugue in. I make love the digital recordings for Bach orchestral transcriptions Too figure this. Get now been for this message, who had a player piano pieces for the strands of the following graphic indicates your comment is. Membership at sheet music. Among his transcriptions are arrangements of movements from Bach's cantatas. JS Bach The Peasant Cantata School Version Pianoforte. The 20 Essential Bach Recordings WQXR Editorial WQXR. -

Elegies for Cello and Piano by Bridge, Britten and Delius: a Study of Traditions and Influences

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2012 Elegies for Cello and Piano by Bridge, Britten and Delius: A Study of Traditions and Influences Sara Gardner Birnbaum University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Birnbaum, Sara Gardner, "Elegies for Cello and Piano by Bridge, Britten and Delius: A Study of Traditions and Influences" (2012). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 7. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/7 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained and attached hereto needed written permission statements(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine). I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless a preapproved embargo applies. -

For All the Attention Paid to the Striking Passage of Thirty-Four

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Humanities Commons for Jane, on our thirty-fourth Accents of Remorse The good has never been perfect. There is always some flaw in it, some defect. First Sightings For all the attention paid to the “interview” scene in Benjamin Britten’s opera Billy Budd, its musical depths have proved remarkably resistant to analysis and have remained unplumbed. This striking passage of thirty-four whole-note chords has probably attracted more comment than any other in the opera since Andrew Porter first spotted shortly after the 1951 premiere that all the chords harmonize members of the F major triad, leading to much discussion over whether or not the passage is “in F major.” 1 Beyond Porter’s perception, the structure was far from obvious, perhaps in some way unprecedented, and has remained mysterious. Indeed, it is the undisputed gnomic power of its strangeness that attracted (and still attracts) most comment. Arnold Whittall has shown that no functional harmonic or contrapuntal explanation of the passage is satisfactory, and proceeded from there to make the interesting assertion that that was the point: The “creative indecision”2 that characterizes the music of the opera was meant to confront the listener with the same sort of difficulty as the layers of irony in Herman Melville’s “inside narrative,” on which the opera is based. To quote a single sentence of the original story that itself contains several layers of ironic ambiguity, a sentence thought by some—I believe mistakenly—to say that Vere felt no remorse: 1. -

Britten Spring Symphony Welcome Ode • Psalm 150

BRITTEN SPRING SYMPHONY WELCOME ODE • PSALM 150 Elizabeth Gale soprano London Symphony Chorus Alfreda Hodgson contralto Martyn Hill tenor London Symphony Orchestra Southend Boys’ Choir Richard Hickox Greg Barrett Richard Hickox (1948 – 2008) Benjamin Britten (1913 – 1976) Spring Symphony, Op. 44* 44:44 For Soprano, Alto and Tenor solos, Mixed Chorus, Boys’ Choir and Orchestra Part I 1 Introduction. Lento, senza rigore 10:03 2 The Merry Cuckoo. Vivace 1:57 3 Spring, the Sweet Spring. Allegro con slancio 1:47 4 The Driving Boy. Allegro molto 1:58 5 The Morning Star. Molto moderato ma giocoso 3:07 Part II 6 Welcome Maids of Honour. Allegretto rubato 2:38 7 Waters Above. Molto moderato e tranquillo 2:23 8 Out on the Lawn I lie in Bed. Adagio molto tranquillo 6:37 Part III 9 When will my May come. Allegro impetuoso 2:25 10 Fair and Fair. Allegretto grazioso 2:13 11 Sound the Flute. Allegretto molto mosso 1:24 Part IV 12 Finale. Moderato alla valse – Allegro pesante 7:56 3 Welcome Ode, Op. 95† 8:16 13 1 March. Broad and rhythmic (Maestoso) 1:52 14 2 Jig. Quick 1:20 15 3 Roundel. Slower 2:38 16 4 Modulation 0:39 17 5 Canon. Moving on 1:46 18 Psalm 150, Op. 67‡ 5:31 Kurt-Hans Goedicke, LSO timpani Lively March – Lightly – Very lively TT 58:48 4 Elizabeth Gale soprano* Alfreda Hodgson contralto* Martyn Hill tenor* The Southend Boys’ Choir* Michael Crabb director Senior Choirs of the City of London School for Girls† Maggie Donnelly director Senior Choirs of the City of London School† Anthony Gould director Junior Choirs of the City of London School -

What Handel Taught the Viennese About the Trombone

291 What Handel Taught the Viennese about the Trombone David M. Guion Vienna became the musical capital of the world in the late eighteenth century, largely because its composers so successfully adapted and blended the best of the various national styles: German, Italian, French, and, yes, English. Handel’s oratorios were well known to the Viennese and very influential.1 His influence extended even to the way most of the greatest of them wrote trombone parts. It is well known that Viennese composers used the trombone extensively at a time when it was little used elsewhere in the world. While Fux, Caldara, and their contemporaries were using the trombone not only routinely to double the chorus in their liturgical music and sacred dramas, but also frequently as a solo instrument, composers elsewhere used it sparingly if at all. The trombone was virtually unknown in France. It had disappeared from German courts and was no longer automatically used by composers working in German towns. J.S. Bach used the trombone in only fifteen of his more than 200 extant cantatas. Trombonists were on the payroll of San Petronio in Bologna as late as 1729, apparently longer than in most major Italian churches, and in the town band (Concerto Palatino) until 1779. But they were available in England only between about 1738 and 1741. Handel called for them in Saul and Israel in Egypt. It is my contention that the influence of these two oratorios on Gluck and Haydn changed the way Viennese composers wrote trombone parts. Fux, Caldara, and the generations that followed used trombones only in church music and oratorios. -

Benjamin Britten: a Catalogue of the Orchestral Music

BENJAMIN BRITTEN: A CATALOGUE OF THE ORCHESTRAL MUSIC 1928: “Quatre Chansons Francaises” for soprano and orchestra: 13 minutes 1930: Two Portraits for string orchestra: 15 minutes 1931: Two Psalms for chorus and orchestra Ballet “Plymouth Town” for small orchestra: 27 minutes 1932: Sinfonietta, op.1: 14 minutes Double Concerto in B minor for Violin, Viola and Orchestra: 21 minutes (unfinished) 1934: “Simple Symphony” for strings, op.4: 14 minutes 1936: “Our Hunting Fathers” for soprano or tenor and orchestra, op. 8: 29 minutes “Soirees musicales” for orchestra, op.9: 11 minutes 1937: Variations on a theme of Frank Bridge for string orchestra, op. 10: 27 minutes “Mont Juic” for orchestra, op.12: 11 minutes (with Sir Lennox Berkeley) “The Company of Heaven” for two speakers, soprano, tenor, chorus, timpani, organ and string orchestra: 49 minutes 1938/45: Piano Concerto in D major, op. 13: 34 minutes 1939: “Ballad of Heroes” for soprano or tenor, chorus and orchestra, op.14: 17 minutes 1939/58: Violin Concerto, op. 15: 34 minutes 1939: “Young Apollo” for Piano and strings, op. 16: 7 minutes (withdrawn) “Les Illuminations” for soprano or tenor and strings, op.18: 22 minutes 1939-40: Overture “Canadian Carnival”, op.19: 14 minutes 1940: “Sinfonia da Requiem”, op.20: 21 minutes 1940/54: Diversions for Piano(Left Hand) and orchestra, op.21: 23 minutes 1941: “Matinees musicales” for orchestra, op. 24: 13 minutes “Scottish Ballad” for Two Pianos and Orchestra, op. 26: 15 minutes “An American Overture”, op. 27: 10 minutes 1943: Prelude and Fugue for eighteen solo strings, op. 29: 8 minutes Serenade for tenor, horn and strings, op. -

Copland As Mentor to Britten, 1939-1942

'You absolutely owe it to England to stay here': Copland as mentor to Britten, 1939-1942 Suzanne Robinson Few details of the circumstances of Benjamin Copland to visit him for the weekend at his home in a Britten's stay in America in the years 1939-42 were converted mill in Snape. On this occasion they familiar- known before the publication in 1991of Britten's letters ised one another with their music; Copland played his and, in 1992, of a biography by Humphrey Carpenter. school opera, The Second Hurricane, singing all the parts And with the exception of a short article on Aaron himself, while Britten performed the first version of his Copland and Britten in an Aldeburgh Festival Programme Piano ~oncerto.~Being July, and England, at the first ~ook,llittle attention has been paid to the significance sign of sunshine the locals escorted their visitor to one of Britten's exposure to Copland's music, which Britten of Suffolk's pebbled beaches (which Copland described regarded as the best America had to offer. More than 20 as a 'shingle'). Copland realised that perhaps he was letters survive between 'Benjie' and 'my dearest Aaron', more accustomed to the effects of the sun, when Ibefore the majority of them belonging to the war years when long it became clear that the assembled group was in Copland was resident in New York and Britten was, for danger of "roasting". When I politely pointed out the the most part, nearby in Long ~sland.~Britten fre- obvious result to be expected from lying unprotected quently referred to Copland as his 'very dear friend', on the beach, I was told: "But we see the sun so and even 'Father' (Copland was the senior of the two rarely"'? When he returned to America, copland wrote by 13 years). -

Britten Connections a Guide for Performers and Programmers

Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Britten –Pears Foundation Telephone 01728 451 700 The Red House, Golf Lane, [email protected] Aldeburgh, Suffolk, IP15 5PZ www.brittenpears.org Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Contents The twentieth century’s Programming tips for 03 consummate musician 07 13 selected Britten works Britten connected 20 26 Timeline CD sampler tracks The Britten-Pears Foundation is grateful to Orchestra, Naxos, Nimbus Records, NMC the following for permission to use the Recordings, Onyx Classics. EMI recordings recordings featured on the CD sampler: BBC, are licensed courtesy of EMI Classics, Decca Classics, EMI Classics, Hyperion Records, www.emiclassics.com For full track details, 28 Lammas Records, London Philharmonic and all label websites, see pages 26-27. Index of featured works Front cover : Britten in 1938. Photo: Howard Coster © National Portrait Gallery, London. Above: Britten in his composition studio at The Red House, c1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton . 29 Further information Opposite left : Conducting a rehearsal, early 1950s. Opposite right : Demonstrating how to make 'slung mugs' sound like raindrops for Noye's Fludde , 1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton. Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers 03 The twentieth century's consummate musician In his tweed jackets and woollen ties, and When asked as a boy what he planned to be He had, of course, a great guide and mentor. with his plummy accent, country houses and when he grew up, Britten confidently The English composer Frank Bridge began royal connections, Benjamin Britten looked replied: ‘A composer.’ ‘But what else ?’ was the teaching composition to the teenage Britten every inch the English gentleman. -

Curlew River a PARABLE for CHURCH PERFORMANCE Op

The Yale School of Music, Robert Blocker, Dean and The Institute of Sacred Music, Margot Fassler, Dean present in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Music degree: The Yale Recital Chorus BENJAMIN BRITTEN Curlew River A PARABLE FOR CHURCH PERFORMANCE Op. 71 Libretto based on the medieval Japanese No-play Sumidagawa of Juro Motomasa (1395-1431) by WILLIAM PLOMER Christopher Hossfeld, conductor 5:00 pm 25 January 2004 Christ Church, New Haven 2 No production can go on without the help of many others and this one is no exception. I owe countless thanks and immeasurable gratitude to those who have made today’s recital possible: To my teachers, Maggi Brooks and Simon Carrington, for the guidance in exploring Curlew River and the tools to bring it to the ears of others. To my manager, Evan, for the legwork that brought everything together. To Robert Lehman and Christ Church, for allowing us to use this wonderful space. To my colleagues, Chuck, Holland, Rick, Kim, Joe, David, Michael, Evan, and Richard, for their time, musicality, advice, and expertise to learn this difficult music and make it happen. To my parents, Linda and Rod, my sister, Emily, my fiancé, Jimmy, and all the family and friends who made the journey to New Haven today, for their constant and enduring love and support. 3 PERFORMERS who make up the cast of the Parable: The Madwoman Charles Kamm, Tenor The Ferryman Holland Jancaitis, Baritone The Traveller Rick Hoffenberg, Baritone The Spirit of the Boy Kimberly Dunn, Soprano The Abbot Joseph Gregorio, Bass -

Proquest Dissertations

Benjamin Britten's Nocturnal, Op. 70 for guitar: A novel approach to program music and variation structure Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Alcaraz, Roberto Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 02/10/2021 13:06:08 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/279989 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be f^ any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitlsd. Brolcen or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author dkl not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectk)ning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6' x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additkxial charge.