River Songs (2002) and the Brief Light (2010)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

18 Contemporary Opera and the Failure of Language

18 CONTEMPORARY OPERA AND THE FAILURE OF LANGUAGE Amy Bauer Opera after 1945 presents what Robert Fink has called ‘a strange series of paradoxes to the historian’.1 The second half of the twentieth century saw new opera houses and companies pro- liferating across Europe and America, while the core operatic repertory focused on nineteenth- century works. The collapse of touring companies confined opera to large metropolitan centres, while Cold War cultural politics often limited the appeal of new works. Those new works, whether written with political intent or not, remained wedded historically to ‘realism, illusion- ism, and representation’, as Carolyn Abbate would have it (as opposed to Brechtian alienation or detachment).2 Few operas embraced the challenge modernism presents for opera. Those few early modernist operas accepted into the canon, such as Alban Berg’s Wozzeck, while revolu- tionary in their musical language and subject matter, hew closely to the nature of opera in its nineteenth-century form as a primarily representational medium. As Edward Cone and Peter Kivy point out, they bracket off that medium of representation – the character singing speech, for instance, in an emblematic translation of her native tongue – to blur diegetic song, ‘operatic song’ and a host of other conventions.3 Well-regarded operas in the immediate post-war period, by composers such as Samuel Barber, Benjamin Britten, Francis Poulenc and Douglas Moore, added new subjects and themes while retreating from the formal and tonal challenges of Berg and Schoenberg. -

News Release

news release FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE PRESS CONTACT: Maggie Stapleton, Jensen Artists September 25, 2019 646.536.7864 x2; [email protected] American Composers Orchestra Announces 2019-2020 Season Derek Bermel, Artistic Director & George Manahan, Music Director Two Concerts presented by Carnegie Hall New England Echoes on November 13, 2019 & The Natural Order on April 2, 2020 at Zankel Hall Premieres by Mark Adamo, John Luther Adams, Matthew Aucoin, Hilary Purrington, & Nina C. Young Featuring soloists Jamie Barton, mezzo-soprano; JIJI, guitar; David Tinervia, baritone & Jeffrey Zeigler, cello The 29th Annual Underwood New Music Readings March 12 & 13, 2020 at Aaron Davis Hall at The City College of New York ACO’s annual roundup of the country’s brightest young and emerging composers EarShot Readings January 28 & 29, 2020 with Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra May 5 & 6, 2020 with Houston Symphony Third Annual Commission Club with composer Mark Adamo to support the creation of Last Year ACO Gala 2020 honoring Anthony Roth Constanzo, Jesse Rosen, & Yolanda Wyns March 4, 2020 at Bryant Park Grill www.americancomposers.org New York, NY – American Composers Orchestra (ACO) announces its full 2019-2020 season of performances and engagements, under the leadership of Artistic Director Derek Bermel, Music Director George Manahan, and President Edward Yim. ACO continues its commitment to the creation, performance, preservation, and promotion of music by 1 American Composers Orchestra – 2019-2020 Season Overview American composers with programming that sparks curiosity and reflects geographic, stylistic, racial and gender diversity. ACO’s concerts at Carnegie Hall on November 13, 2019 and April 2, 2020 include major premieres by 2015 Rome Prize winner Mark Adamo, 2014 Pulitzer Prize winner John Luther Adams, 2018 MacArthur Fellow Matthew Aucoin, 2017 ACO Underwood Commission winner Hilary Purrington, and 2013 ACO Underwood Audience Choice Award winner Nina C. -

Download Booklet

Cast in order of appearence Gordon Getty (born 1933) PLUMP JACK Henry IV / Pistol - Christopher Robertson, Bass-baritone Hal (Henry V) - Nikolai Schukoff, Tenor Libretto by the composer after Shakespeare (Henry IV Part 1 & 2, Henry V) Opera in Two Acts Boy / Clarence - Melody Moore, Soprano Bardolph / Chief Justice - Nathaniel Webster, Baritone Concert Version (Scene 1 and Scene 8 of the opera are not included in the concert version) Falstaff - Lester Lynch, Baritone First Traveler - Diana Kehrig, Mezzo-soprano Act One 1 Overture 11. 18 Second Traveler / Second Captain/ Warwick - Bruce Rameker, Baritone 2 Scene 2: “Hal’s Memory” 3. 27 Hostess (Nell Quickly) - Susanne Mentzer, Mezzo-soprano (Henry IV, Hal) Shallow / First Captain - Robert Breault, Tenor 3 Scene 3: “Gad’s Hill” 3. 35 Davy - Chester Patton, Bass-baritone (Falstaff, Hal, Boy, 1st Traveler, 2nd Traveler, Bardolph, Pistol) 4 Scene 4: “Clarence” 5. 16 Chor des Bayerischen Rundfunks (Henry IV, Chief Justice, Clarence) Chorus Master: Florian Helgath 5 Scene 5: “Boar’s Head Inn” 9. 00 (Falstaff, Hal, Hostess, Boy, Pistol, 1st Captain, 2nd Captain ) Münchner Rundfunkorchester Concertmaster: Olga Pogorelova Act Two 6 Scene 6: “Shallow’s Orchard” 5. 04 conducted by: Ulf Schirmer (Shallow, Falstaff) 7 Scene 7: “Jerusalem” 6. 33 Recording Venue: Studio One of the Bavarian Radio Munich, May 2011 (Clarence, Chief Justice, Henry IV, Warwick, Hal, Chorus) Executive Producers: Lisa Delan (Rork Music), Veronika Weber & Florian Lang (Bavarian 8 Scene 9: “Pistol’s News” 4. 47 Radio), Job Maarse (PentaTone Music) (Davy, Falstaff, Bardolph, Shallow, Pistol, Chorus) Recording Producer: Job Maarse 9 Scene 10: “Banishment” 10. -

Kent Tritle's 2014-15 Season

Contact: Jennifer Wada 718-855-7101 [email protected] KENT TRITLE’S 2014-15 SEASON: Verdi’s Requiem in a Unique Collaboration Early and New Music in Great Music in a Great Space at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine Tenth Anniversary Season with Oratorio Society of New York World Premieres of Works by Filas, Gilbertson, Paterson, with Musica Sacra Manhattan School of Music Chamber Choir at The Metropolitan Museum of Art More New York Synergy: Musica Sacra with Orchestra of St. Luke’s A performance of Verdi’s Requiem that is a tripartite collaboration highlights the 2014-15 season of Kent Tritle, called “New York’s reigning choral conductor” by The New York Times. In an event emblematic of Kent’s multiple roles in the city’s choral life, he will conduct a performance of the massive work by the Oratorio Society of New York, of which he is Music Director, and the Symphony and Symphonic Chorus of the Manhattan School of Music, where he is Director of Choral Activities, in the grand space of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, where he is Director of Cathedral Music and Organist – with a new choral configuration that features the more-than-250 singers on risers in the cathedral’s Great Choir space. The program is perhaps Tritle’s most ambitious yet at the Cathedral, where he marks his fourth season in 2014-15 also with concerts of early music and contemporary works by the professional Cathedral Choir, and holiday programs. The season also marks Kent’s tenth anniversary as Music Director of the 200-voice avocational Oratorio Society of New York (he has just renewed his contract through 2016-17), which he will lead in three Carnegie Hall concerts of grand choral repertoire; it is also his eighth season as Music Director of the acclaimed professional chorus Musica Sacra, and they will highlight their season with a program of three world premieres. -

CARMINA BURANA Thursday, March 28 at 7 P.M

CLASSICAL SERIES 2018/19 SEASON CARMINA BURANA Thursday, March 28 at 7 p.m. Friday and Saturday, March 29-30 at 8 p.m. Sunday, March 31 at 2 p.m. RYAN McADAMS, guest conductor SARAH KIRKLAND Something for the Dark SNIDER AUGUSTA READ EOS (Goddess of the Dawn), a Ballet for Orchestra THOMAS I. Dawn V. Spring Rain II. Daybright and Firebright VI. Golden Chariot III. Shimmering VII. Sunlight IV. Dreams and Memories INTERMISSION ORFF Carmina burana Fortuna Imperatrix Mundi (Fortune, Empress of the World) Part I. Primo vere (In Springtime) Uf dem anger (On the lawn) Part II. In taberna (In the Tavern) Part III. Cour d’amours (The Court of Love) Blanziflor et Helena (Blanchefleur and Helen) Fortuna Imperatrix Mundi JENNIFER ZETLAN, soprano | NICHOLAS PHAN, tenor | HUGH RUSSELL, baritone KANSAS CITY SYMPHONY CHORUS, CHARLES BRUFFY, chorus director LAWRENCE CHILDREN’S CHOIR, CAROLYN WELCH, artistic director *See program insert for Carmina Burana text and translation. The 2018/19 season is generously sponsored by Friday’s concert sponsored by SHIRLEY and BARNETT C. HELZBERG, JR. JIM AND JUDY HEETER Saturday’s concert sponsored by The Classical Series is sponsored by CAROL AND JOHN KORNITZER Guest Conductor Ryan McAdams sponsored by ANN MARIE TRASK Additional support provided by R. Crosby Kemper, Jr. Fund Podcast available at kcsymphony.org KANSAS CITY SYMPHONY 43 Kansas City Symphony PROGRAM NOTES By Ken Meltzer SARAH KIRKLAND SNIDER (b. 1973) Something for the Dark (2016) 12 minutes Piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, 3 clarinets, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 4 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, chimes, crotales, cymbals, glockenspiel, marimba, sleigh bells, snare drum, suspended cymbals, tam-tam, tom-toms, triangle, vibraphone, harp, piano, celesta and strings. -

Boris Godunov Biographies

Boris Godunov Biographies Cast Stanislav Trofimov (Boris Godunov) began his operatic career in the Chelyabinsk Opera House in 2008, and went on to perform leading bass roles at the Ekaterinburg Opera House (the Bolshoi Theatre) and other opera theaters across Russia. He became a soloist at the Mariinsky Theatre in 2016. Mr. Trofimov has portrayed numerous leading roles including Boris Godunov (Boris Godunov), Philip II (Don Carlos), Procida (I vespri siciliani), Fiesco (Simon Boccanegra), Konchak (Prince Igor), Ivan Susanin (Life of the Tsar), Sobakin (Tsar’s Bride), Prince Yuri Vsevolodovich (The Legend of the Invisible City of Kitezh and the Maiden Fevronia), Prince Gremin (Eugene Onegin), Ferrando (Il Trovatore), Don Bartolo (Le nozze di Figaro), and Old Hebrew (Samson et Dalila). Recent performances include Procida in Mariinsky’s new production of I vespri siciliani, Zaccaria in Nabucco at the opening of Arena di Verona Summer Festival, a tour with the Bolshoi Theatre as Archbishop in The Maid of Orleans in France, and performances at the Salzburg Festival as Priest in the new production of Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District. Mr. Trofimov will appear at the 2018 Salzburg Festival and at Teatro alla Scala in 2019. These performances mark his San Francisco Symphony debut. This season, Cuban-American mezzo-soprano Eliza Bonet (Fyodor) made her debut at the Kennedy Center as a member of the Washington National Opera’s Domingo-Cafritz Young Artist Program, singing the role of Bradamante in Handel’s Alcina. As a part of this season’s nationwide Bernstein at 100 celebrations, Ms. Bonet performs as Paquette in Candide with the WNO, and with National Symphony Orchestra in West Side Story. -

Vocal Solos and Opera

vocal solos and opera Complete Catalog STEPHEN CHATMAN AND TARA WOHLBERG Choir Practice Companion Products Soloists, SATB, and Piano Choral Part, 7.0656 Moderately Diffi cult Study Score, 7.0657 7.0655, Piano/Vocal Score $35.00 Libretto, 7.0669 CONTENTS New & Featured Opera 3 One Act Opera 5 New CD from David Conte Full Length Opera 8 Everyone Sang New Art Songs 10–11 Vocal Music of David Conte is two-disc set includes recordings of Vocal Solos - Complete Listing 12 David Conte’s most recent vocal composi- tion o erings from collections “American Death Ballads;” “ ree Poems of Christina Opera Anthologies 22 Rossetti;” “Love Songs;” “Everyone Sang;” “Lincoln;” “Sexton Songs;” and “Requiem Opera - Complete Listing 23 Songs.” CD182 $24.95 Opera Scenes 24 Opera Anthologies Opera Aria Anthology, Opera Aria Anthology, Volume 1: (Soprano) Volume 2: (Mezzo-Sopra- Compiled by Craig W. Hanson no) Edited by Stanley M. Ho man Compiled by Craig W. Hanson Arias for soprano from operas by David Edited by Stanley M. Ho man Conte, Daron Hagen, Libby Larsen, Arias for mezzo-soprano from operas Henry Mollicone, Ronald Perera, Conrad by David Conte, Daron Hagen, Henry Susa, and Robert Ward. 152 pages. Mollicone, Douglas Moore, Ronald Perera, 6000 $33.60 Conrad Susa, and Robert Ward. 142 pages. 6001 $33.60 Opera Aria Anthology, Opera Aria Anthology, Volume 3: (Tenor) Volume 4: (Baritone) Compiled by Craig W. Hanson Compiled by Craig W. Hanson Edited by Stanley M. Ho man Edited by Stanley M. Ho man Arias for tenor from operas by David Arias for baritone from operas by David Conte, Henry Mollicone, Ronald Perera, Conte, John David Earnest, Daron Hagen, Conrad Susa, and Robert Ward. -

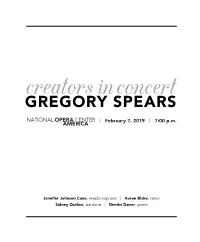

Creators in Concert: Gregory Spears Program

creators in concert GREGORY SPEARS NATIONAL OPERA CENTER | February 7, 2019 | 7:00 p.m. AMERICA Jennifer Johnson Cano, mezzo-soprano | Aaron Blake, tenor Sidney Outlaw, baritone | Dimitri Dover, piano PROGRAM “Aquehonga” (2017) A song with words by Raphael Allison Jennifer Johnson Cano “Last Night” from Fellow Travelers (2016) An opera based on the novel by Thomas Mallon Libretto by Greg Pierce Aaron Blake “English Teacher’s Aria” from Paul’s Case (2013) An opera based on the short story by Willa Cather Libretto by Kathryn Walat and Gregory Spears Jennifer Johnson Cano, Aaron Blake, Sidney Outlaw “Our Very Own Home” from Fellow Travelers (2016) An opera based on the novel by Thomas Mallon Libretto by Greg Pierce Sidney Outlaw “Fearsome This Night” from Wolf-in-Skins (2013) A dance-opera based on Welsh mythology Libretto by Christopher Williams Jennifer Johnson Cano CONVERSATION WITH MARC A. SCORCA, PRESIDENT/CEO, OPERA AMERICA Jennifer Johnson Cano and Aaron Blake appear courtesy of the Metropolitan Opera. [Headshot, credit: Rebecca Allan] ABOUT THE COMPOSER GREGORY SPEARS is a New York-based composer whose music has been called “astonishingly beautiful” (The New York Times), “coolly entrancing” (The New Yorker) and “some of the most beautifully unsettling music to appear in recent memory” (The Boston Globe). In recent seasons he has been commissioned by Lyric Opera of Chicago, Cincinnati Opera, Houston Grand Opera, Seraphic Fire, The Crossing, BMI and Concert Artists Guild, Vocal Arts DC, New York Polyphony, The New York International Piano Competition, and the JACK Quartet. Spears’ most recent evening-length opera, Fellow Travelers, written in collaboration with Greg Pierce, premiered at Cincinnati Opera in 2016 and has since been seen at the PROTOTYPE Festival, Lyric Opera of Chicago and Minnesota Opera. -

An Analytical Study of the Britten Violin Concerto, Op.15 Shr-Han Wu University of South Carolina

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2017 An Analytical Study of the Britten Violin Concerto, Op.15 Shr-Han Wu University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Wu, S.(2017). An Analytical Study of the Britten Violin Concerto, Op.15. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/4131 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN ANALYTICAL STUDY OF THE BRITTEN VIOLIN CONCERTO, OP.15 by Shr-Han Wu Bachelor of Music National Sun Yat-sen University, 2009 Master of Music University of South Carolina, 2011 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music Performance School of Music University of South Carolina 2017 Accepted by: Donald Portnoy, Major Professor Craig Butterfield, Committee Member William Terwilliger, Committee Member Sarah Williams, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Shr-Han Wu, 2017 All Rights Reserve ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am grateful to Boosey&Hawkes for the kind permission to use Violin Concerto, Op. 15 by Benjamin Britten © Copyright 1940 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd., Three Pieces from “Suite, Op. 6” by Benjamin Britten © Copyright 1940 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd., and “Passacaglia” from Peter Grimes, Op. 33 by Benjamin Britten. © Copyright 1940 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. -

Rod Gilfry Makes Matt Aucoin's 'Crossing' Sing

OPERA REVIEW Rod Gilfry makes Matt Aucoin’s ‘Crossing’ sing GRETJEN HELENE/ART Rod Gilfry as Walt Whitman and Alexander Lewis as a wounded soldier in Matthew Aucoin’s “Crossing.” By Jeffrey Gantz GLOBE CORRESPONDENT JUNE 01, 2015 Walt Whitman was not a composer, but he did hear America singing, and in his youth the poet was enamored of Italian bel canto. He even averred that had it not been for Bellini and Donizetti, he could never have written “Leaves of Grass.” So there’s a logic to Matthew Aucoin’s choice of Whitman’s Civil War journals as the inspiration for his new opera, which is getting its world premiere from the American Repertory Theater at the Citi Shubert Theatre. “Crossing” is an ambitious work with much to recommend it, not least Rod Gilfry’s extraordinary performance as Whitman. At 25, Aucoin, a Medfield native and Harvard grad, has commissions from the Lyric Opera of Chicago and the Metropolitan Opera, where he’s served as an assistant conductor. The subject of recent glowing features in The New York Times Magazine and The Wall Street Journal, he’s also an accomplished pianist and poet. His opera — for which he wrote both music and libretto, and which he is conducting at the Shubert — is part of the National Civil War Project, a multi-year, multi-city endeavor in commemoration of the war’s 150th anniversary. (Among the works the ART has already staged are the Lisps’ indie-rock musical “Futurity” and the first three parts of Pulitzer winner Suzan-Lori Parks’s “Father Comes Home From the Wars.”) CONTINUE READING BELOW ▼ “Crossing” is opera at its most elemental, something Whitman would have appreciated. -

Crossingin CONCERT

FREE! Paul Crewes Rachel Fine Plácido Domingo James Conlon Christopher Koelsch FOR ALL AGES Dance Artistic Director Managing Director Eli and Edythe Broad Richard Seaver Sebastian Paul and General Director Music Director Marybelle Musco Sundays President and CEO PRESENT with Debbie Allen & Friends Matthew Aucoin’s EVERY SECOND SUNDAY OF THE MONTH IN CONCERT ® Crossing Three-time Emmy Award- winner Debbie Allen is back for MUSIC AND LIBRETTO BY the third season running with Matthew Aucoin her wildly popular Dance inspired by the poetry and prose of Walt Whitman Sundays, an exhilarating series CONDUCTOR of FREE, outdoor dance events Matthew Aucoin for the whole family! Members of the LA Opera Orchestra May 13 | 12pm – 2pm Principal Cast (in order of vocal appearance) AFRICAN DANCE Accompanied by live ROD GILFRY...........................................................................WALT WHITMAN drummers. BRENTON RYAN ‡ ...............................................................JOHN WORMLEY June 10 | 5pm - 7pm DAVÓNE TINES * ............................................................FREDDIE STOWERS VOGUE LIV REDPATH † ...........................................................................MESSENGER Celebrate Pride and unleash your inner diva as you learn the * LA Opera debut LA Opera Off Grand and Matthew Aucoin’s basics of Voguing. † Member of LA Opera’s residency made possible by a generous grant from Domingo-Colburn-Stein Young Artist Program The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation July 8 | 5pm – 7pm ‡ Alumnus of LA Opera’s Domingo-Colburn-Stein Young Artist Program Additional support from Contemporary Opera Initiative SALSA SUNDAY chairpersons Barry and Nancy Sanders and a consortium Taught by Debbie Allen herself! PRODUCTION STAFF of generous donors STAGE MANAGER Erin Thompson-Janszen Crossing was commissioned by the American Repertory Theater. The A.R.T. also produced the August 12 | 5pm – 7pm work’s first production, in cooperation with Music Theatre Group. -

Review: Matthew Aucoin's 'Crossing' Is a Taut, Inspired Opera

http://nyti.ms/1ADboHR MUSIC Review: Matthew Aucoin’s ‘Crossing’ Is a Taut, Inspired Opera By ANTHONY TOMMASINI MAY 31, 2015 BOSTON — At 25, the American composer, conductor, pianist, poet and sometime critic Matthew Aucoin has already been an assistant conductor at the Metropolitan Opera, made his conducting debut with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and written pieces for Yo-Yo Ma, among other renowned artists, not to mention lecturing on music and poetry at the Shakespeare Society in New York. What seems clear, after the premiere of his opera “Crossing” on Friday night here at the Shubert Theater in the Citi Performing Arts Center, is that Mr. Aucoin is also afire for the genre of opera. Presented by the American Repertory Theater, based in Cambridge, in association with Music-Theater Group, “Crossing” is a taut, teeming and inspired work. With a libretto by Mr. Aucoin, the opera is based on the diaries of Walt Whitman from his transformative experience tending to wounded soldiers during the Civil War at makeshift hospitals on the outskirts of Washington. Though certain aspects of the score suggest that Mr. Aucoin has yet to define fully his composer’s voice, he clearly has prodigious gifts. The music grabbed me right through the opera’s 1-hour-40-minute running time, without intermission, especially as played here by the dynamic chamber orchestra A Far Cry, conducted by Mr. Aucoin. His score draws upon myriad modernist and Neo-Classical styles, with hints of Britten, Bernstein, Thomas Adès, techno and much more. With his acute ear and abundant technique, Mr.