Highs and Lows of the Baritenor Voice: Exploring

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’S Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 10-3-2014 The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M. May University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation May, Joshua M., "The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 580. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/580 ABSTRACT The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua Michael May University of Connecticut, 2014 W. A. Mozart’s opera and concert arias for tenor are among the first music written specifically for this voice type as it is understood today, and they form an essential pillar of the pedagogy and repertoire for the modern tenor voice. Yet while the opera arias have received a great deal of attention from scholars of the vocal literature, the concert arias have been comparatively overlooked; they are neglected also in relation to their counterparts for soprano, about which a great deal has been written. There has been some pedagogical discussion of the tenor concert arias in relation to the correction of vocal faults, but otherwise they have received little scrutiny. This is surprising, not least because in most cases Mozart’s concert arias were composed for singers with whom he also worked in the opera house, and Mozart always paid close attention to the particular capabilities of the musicians for whom he wrote: these arias offer us unusually intimate insights into how a first-rank composer explored and shaped the potential of the newly-emerging voice type of the modern tenor voice. -

Falsetto Head Voice Tips to Develop Head Voice

Volume 1 Issue 27 September 04, 2012 Mike Blackwood, Bill Wiard, Editors CALENDAR Current Songs (Not necessarily “new”) Goodnight Sweetheart, Goodnight Spiritual Medley Home on the Range You Raise Me Up Just in Time Question: What’s the difference between head voice and falsetto? (Contunued) Answer: Falsetto Notice the word "falsetto" contains the word "false!" That's exactly what it is - a false impression of the female voice. This occurs when a man who is naturally a baritone or bass attempts to imitate a female's voice. The sound is usually higher pitched than the singer's normal singing voice. The falsetto tone produced has a head voice type quality, but is not head voice. Falsetto is the lightest form of vocal production that the human voice can make. It has limited strength, tones, and dynamics. Oftentimes when singing falsetto, your voice may break, jump, or have an airy sound because the vocal cords are not completely closed. Head Voice Head voice is singing in which the upper range of the voice is used. It's a natural high pitch that flows evenly and completely. It's called head voice or "head register" because the singer actually feels the vibrations of the sung notes in their head. When singing in head voice, the vocal cords are closed and the voice tone is pure. The singer is able to choose any dynamic level he wants while singing. Unlike falsetto, head voice gives a connected sound and creates a smoother harmony. Tips to Develop Head Voice If you want to have a smooth tone and develop a head voice singing talent, you can practice closing the gap with breathing techniques on every note. -

Gioachino Rossini

GIOACHINO ROSSINI: DESTREZAS VOCALES EN SU DISCURSO MELÓDICO Proyecto de grado para optar al título de MAESTRO EN MÚSICA CON ÉNFASIS EN CANTO LÍRICO Autor: JULIO CÉSAR SALAZAR MOLINA Asesor: CARLOS GODOY PONTIFICIA UNIVERSIDAD JAVERIANA FACULTAD DE ARTES CARRERA DE ESTUDIOS MUSICALES BOGOTA – 20/07/2010 ÍNDICE OBJETIVOS 3 INTRODUCCIÓN 4 1. METODOLOGÍA 5 2. CONTEXTO HISTÓRICO 5 3. EL ESPLENDOR DE LOS CASTRATI 7 4. LA TRADICIÓN DEL BEL CANTO 8 4.1 EL LEGATO 8 4.2 EL VIBRATO 8 4.3 EL PORTAMENTO 9 4.4 LA COLORATURA 10 5. ROSSINI Y LA DESTREZA VOCAL 10 5.1. MOZART, UN ANTECEDENTE EN EL CLASICISMO 11 5.2. EL CROMATISMO Y LA EXPRESIÓN DE EMOCIONES 12 5.3. LA HOMOGENEIDAD DEL TIMBRE 13 5.4 LA ACENTUACIÓN DE LAS PALABRAS 16 5.5 ASPECTOS VOCALES DEL TENOR ROSSINIANO 18 6. CONCLUSIONES 19 7. BIBLIOGRAFÍA 20 APÉNDICES 21 2 GIOACCHINO ROSSINI: DESTREZAS VOCALES EN SU DISCURSO MELÓDICO UN ANÁLISIS INTERPRETATIVO BASADO EN PIEZAS ROSINIANAS PARA TENOR OBJETIVO GENERAL Observar las principales características del discurso melódico rosiniano e identificar las destrezas vocales requeridas con el fin de tomar decisiones interpretativas para el repertorio tratado, basadas en el conocimiento adquirido durante la carrera. OBJETIVOS ESPECÍFICOS Contextualizar el tratamiento rosiniano del instrumento vocal dentro de los lineamientos estéticos del bel canto y reconocer sus posibles antecedentes en el clasicismo para así definir una línea evolutiva en el desarrollo del estilo. Reconocer la manera particular en la cual se deben aplicar dentro de este estilo los elementos técnicos trabajados durante el proceso de formación vocal adquirido en la carrera, como son: el legato, el vibrato, el fraseo, la respiración, la ornamentación, la coloratura, las dinámicas, la articulación y la dicción, entre otros. -

Voice Types in Opera

Voice Types in Opera In many of Central City Opera’s educational programs, we spend some time explaining the different voice types – and therefore character types – in opera. Usually in opera, a voice type (soprano, mezzo soprano, tenor, baritone, or bass) has as much to do with the SOUND as with the CHARACTER that the singer portrays. Composers will assign different voice types to characters so that there is a wide variety of vocal colors onstage to give the audience more information about the characters in the story. SOPRANO: “Sopranos get to be the heroine or the princess or the opera star.” – Eureka Street* “Sopranos always get to play the smart, sophisticated, sweet and supreme characters!” – The Great Opera Mix-up* A soprano is a woman’s voice type. There are many different kinds of sopranos within the general category: coloratura, lyric, and spinto are a few. Coloratura soprano: Diana Damrau as The Queen of the Night in The Magic Flute (Mozart): https://youtu.be/dpVV9jShEzU Lyric soprano: Mirella Freni as Mimi in La bohème (Puccini): https://youtu.be/yTagFD_pkNo Spinto soprano: Leontyne Price as Aida in Aida (Verdi): https://youtu.be/IaV6sqFUTQ4?t=1m10s MEZZO SOPRANO: “There are also mezzos with a lower, more exciting woman’s voice…We get to be magical or mythical characters and sometimes… we get to be boys.” – Eureka Street “Mezzos play magnificent, magical, mysterious, and miffed characters.” – The Great Opera Mix-up A mezzo soprano is a woman’s voice type. Just like with sopranos, there are different kinds of mezzo sopranos: coloratura, lyric, and dramatic. -

English Translation of the German by Tom Hammond

Richard Strauss Susan Bullock Sally Burgess John Graham-Hall John Wegner Philharmonia Orchestra Sir Charles Mackerras CHAN 3157(2) (1864 –1949) © Lebrecht Music & Arts Library Photo Music © Lebrecht Richard Strauss Salome Opera in one act Libretto by the composer after Hedwig Lachmann’s German translation of Oscar Wilde’s play of the same name, English translation of the German by Tom Hammond Richard Strauss 3 Herod Antipas, Tetrarch of Judea John Graham-Hall tenor COMPACT DISC ONE Time Page Herodias, his wife Sally Burgess mezzo-soprano Salome, Herod’s stepdaughter Susan Bullock soprano Scene One Jokanaan (John the Baptist) John Wegner baritone 1 ‘How fair the royal Princess Salome looks tonight’ 2:43 [p. 94] Narraboth, Captain of the Guard Andrew Rees tenor Narraboth, Page, First Soldier, Second Soldier Herodias’s page Rebecca de Pont Davies mezzo-soprano 2 ‘After me shall come another’ 2:41 [p. 95] Jokanaan, Second Soldier, First Soldier, Cappadocian, Narraboth, Page First Jew Anton Rich tenor Second Jew Wynne Evans tenor Scene Two Third Jew Colin Judson tenor 3 ‘I will not stay there. I cannot stay there’ 2:09 [p. 96] Fourth Jew Alasdair Elliott tenor Salome, Page, Jokanaan Fifth Jew Jeremy White bass 4 ‘Who spoke then, who was that calling out?’ 3:51 [p. 96] First Nazarene Michael Druiett bass Salome, Second Soldier, Narraboth, Slave, First Soldier, Jokanaan, Page Second Nazarene Robert Parry tenor 5 ‘You will do this for me, Narraboth’ 3:21 [p. 98] First Soldier Graeme Broadbent bass Salome, Narraboth Second Soldier Alan Ewing bass Cappadocian Roger Begley bass Scene Three Slave Gerald Strainer tenor 6 ‘Where is he, he, whose sins are now without number?’ 5:07 [p. -

1 Making the Clarinet Sing

Making the Clarinet Sing: Enhancing Clarinet Tone, Breathing, and Phrase Nuance through Voice Pedagogy D.M.A Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Alyssa Rose Powell, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2020 D.M.A. Document Committee Dr. Caroline A. Hartig, Advisor Dr. Scott McCoy Dr. Eugenia Costa-Giomi Professor Katherine Borst Jones 1 Copyrighted by Alyssa Rose Powell 2020 2 Abstract The clarinet has been favorably compared to the human singing voice since its invention and continues to be sought after for its expressive, singing qualities. How is the clarinet like the human singing voice? What facets of singing do clarinetists strive to imitate? Can voice pedagogy inform clarinet playing to improve technique and artistry? This study begins with a brief historical investigation into the origins of modern voice technique, bel canto, and highlights the way it influenced the development of the clarinet. Bel canto set the standards for tone, expression, and pedagogy in classical western singing which was reflected in the clarinet tradition a hundred years later. Present day clarinetists still use bel canto principles, implying the potential relevance of other facets of modern voice pedagogy. Singing techniques for breathing, tone conceptualization, registration, and timbral nuance are explored along with their possible relevance to clarinet performance. The singer ‘in action’ is presented through an analysis of the phrasing used by Maria Callas in a portion of ‘Donde lieta’ from Puccini’s La Bohème. This demonstrates the influence of text on interpretation for singers. -

Bass-Baritone • Baryton-Basse [email protected] + 1 917 650-0573 1 100 Words Bio

David Mimran - Bass-Baritone • Baryton-Basse [email protected] + 1 917 650-0573 www.davidmimran.net 1 100 words bio Bass-Baritone David Mimran set aside a career as a lawyer in Paris to sing opera in New York. Great vocal flexibility in a wide tessitura, natural acting skills and a knowledge of nine languages including Italian, French, German, English, Spanish and Finnish allow for a large variety of repertoire. Roles on stage include Alcindoro/Benoît in Bohème, Conte Ceprano in Rigoletto, Niejus & Cascada in Merry Widow, Sarastro in Die Zauberflöte, Figaro & Antonio in Le nozze di Figaro, Morales & Zuniga in Carmen, Fiorello in Il Barbiere di Siviglia, Frank in Fledermaus, Lorenzo in I Capuletti e i Montecchi, Achille in Giulio Cesare and Melisso in Alcina. Languages French: Mother tongue English: Bilingual German, Italian, Spanish: Proficient Finnish, Portuguese, Hebrew: Working knowledge Russian, Hungarian: Basic phonetic reading knowledge I would consider studying a new language to sing a role. Stage Experience Full roles performed • Benoît/Alcindoro in Bohème - Opera Company of Brooklyn • Sciarrone/Jailer in Tosca - Regina Opera • Yakuside in Madama Butterfly - Bleecker Street Opera • Niejus and Cascada in The Merry Widow - Amore Opera • Sarastro in Die Zauberflöte - NY Lyric Opera Theater • Fiorello in Il Barbiere di Siviglia - Bleecker Street Opera • Lorenzo in I Capuletti e i Montecchi - Manhattan Chamber Opera • Spinelloccio/Nicolao in Gianni Schicchi - Regina Opera • Achilla in Giulio Cesare - Manhattan Chamber Opera • Docteur -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

Interpreting Tempo and Rubato in Chopin's Music

Interpreting tempo and rubato in Chopin’s music: A matter of tradition or individual style? Li-San Ting A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales School of the Arts and Media Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences June 2013 ABSTRACT The main goal of this thesis is to gain a greater understanding of Chopin performance and interpretation, particularly in relation to tempo and rubato. This thesis is a comparative study between pianists who are associated with the Chopin tradition, primarily the Polish pianists of the early twentieth century, along with French pianists who are connected to Chopin via pedagogical lineage, and several modern pianists playing on period instruments. Through a detailed analysis of tempo and rubato in selected recordings, this thesis will explore the notions of tradition and individuality in Chopin playing, based on principles of pianism and pedagogy that emerge in Chopin’s writings, his composition, and his students’ accounts. Many pianists and teachers assume that a tradition in playing Chopin exists but the basis for this notion is often not made clear. Certain pianists are considered part of the Chopin tradition because of their indirect pedagogical connection to Chopin. I will investigate claims about tradition in Chopin playing in relation to tempo and rubato and highlight similarities and differences in the playing of pianists of the same or different nationality, pedagogical line or era. I will reveal how the literature on Chopin’s principles regarding tempo and rubato relates to any common or unique traits found in selected recordings. -

Lessons for the Vocal Cross-Training Singer and Teacher Lara C

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations Spring 2019 Bel Canto to Punk and Back: Lessons for the Vocal Cross-Training Singer and Teacher Lara C. Wilson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Wilson, L. C.(2019). Bel Canto to Punk and Back: Lessons for the Vocal Cross-Training Singer and Teacher. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/5248 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bel Canto to Punk and Back: Lessons for the Vocal Cross-Training Singer and Teacher by Lara C. Wilson Bachelor of Music Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music, 1991 Master of Music Indiana University, 1997 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Performance School of Music University of South Carolina 2019 Accepted by: E. Jacob Will, Major Professor J. Daniel Jenkins, Committee Member Lynn Kompass, Committee Member Janet Hopkins, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Lara C. Wilson, 2019 All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION To my family, David, Dawn and Lennon Hunt, who have given their constant support and unconditional love. To my Mom, Frances Wilson, who has encouraged me through this challenge, among many, always believing in me. Lastly and most importantly, to my husband Andy Hunt, my greatest fan, who believes in me more sometimes than I believe in myself and whose backing has been unwavering. -

Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 4-15-2018 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Bourne, Thaddaeus, "Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1779. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1779 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus James Bourne, DMA University of Connecticut, 2018 This study will examine the Zwischenfach colloquially referred to as the baritenor. A large body of published research exists regarding the physiology of breathing, the acoustics of singing, and solutions for specific vocal faults. There is similarly a growing body of research into the system of voice classification and repertoire assignment. This paper shall reexamine this research in light of baritenor voices. After establishing the general parameters of healthy vocal technique through appoggio, the various tenor, baritone, and bass Fächer will be studied to establish norms of vocal criteria such as range, timbre, tessitura, and registration for each Fach. The study of these Fächer includes examinations of the historical singers for whom the repertoire was created and how those roles are cast by opera companies in modern times. The specific examination of baritenors follows the same format by examining current and -

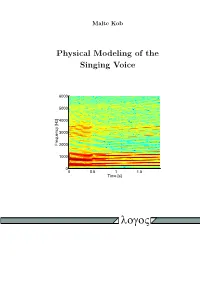

Physical Modeling of the Singing Voice

Malte Kob Physical Modeling of the Singing Voice 6000 5000 4000 3000 Frequency [Hz] 2000 1000 0 0 0.5 1 1.5 Time [s] logoV PHYSICAL MODELING OF THE SINGING VOICE Von der FakulÄat furÄ Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik der Rheinisch-WestfÄalischen Technischen Hochschule Aachen zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines DOKTORS DER INGENIEURWISSENSCHAFTEN genehmigte Dissertation vorgelegt von Diplom-Ingenieur Malte Kob aus Hamburg Berichter: UniversitÄatsprofessor Dr. rer. nat. Michael VorlÄander UniversitÄatsprofessor Dr.-Ing. Peter Vary Professor Dr.-Ing. JuÄrgen Meyer Tag der muÄndlichen PruÄfung: 18. Juni 2002 Diese Dissertation ist auf den Internetseiten der Hochschulbibliothek online verfuÄgbar. Die Deutsche Bibliothek – CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Kob, Malte: Physical modeling of the singing voice / vorgelegt von Malte Kob. - Berlin : Logos-Verl., 2002 Zugl.: Aachen, Techn. Hochsch., Diss., 2002 ISBN 3-89722-997-8 c Copyright Logos Verlag Berlin 2002 Alle Rechte vorbehalten. ISBN 3-89722-997-8 Logos Verlag Berlin Comeniushof, Gubener Str. 47, 10243 Berlin Tel.: +49 030 42 85 10 90 Fax: +49 030 42 85 10 92 INTERNET: http://www.logos-verlag.de ii Meinen Eltern. iii Contents Abstract { Zusammenfassung vii Introduction 1 1 The singer 3 1.1 Voice signal . 4 1.1.1 Harmonic structure . 5 1.1.2 Pitch and amplitude . 6 1.1.3 Harmonics and noise . 7 1.1.4 Choir sound . 8 1.2 Singing styles . 9 1.2.1 Registers . 9 1.2.2 Overtone singing . 10 1.3 Discussion . 11 2 Vocal folds 13 2.1 Biomechanics . 13 2.2 Vocal fold models . 16 2.2.1 Two-mass models . 17 2.2.2 Other models .