An Analytical Study of the Britten Violin Concerto, Op.15 Shr-Han Wu University of South Carolina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INTERVIEW Tasmin Little Records the Elgar Violin Concerto

Tasmin Little records the Elgar Violin Concerto - an interview with Nic... http://www.musicweb-international.com/classrev/2010/Nov10/Elgar_Li... RECORDING OF THE MONTH SPECIAL OFFER RECORDING OF THE MONTH Exceptional £12 Post free worldwide ELGAR The Kingdom Elder 2CDS ONLY £12 post free Worldwide Search What's New Classical CD Reviews Live Reviews Jazz CD Reviews Composers Resources Contact Us Classical CD and DVD reviews. MusicWeb is not a subscription site and it is our advertisers that pay for it. Please visit their sites regularly to see if anything might interest you. Purchasing from them keeps MusicWeb free. Classical Editor: Rob Barnett Founder Len Mullenger EXPLORE Advertising Rates INTERVIEW Printable version Visitor stats Musicweb - CLICK MusicWeb International has over 30,000 Classical CD reviews on offer Tasmin Little records the Elgar Violin Concerto - an interview with Nick Barnard With the major release of a long-awaited recording from Gerard Hoffnung Concerts & one of Britain’s best-loved and The Bricklayer Story Shostakovich Symph. 10 finest violinists imminent, RLPO Petrenko MusicWeb can now offer £4.99 post free Tasmin Little very kindly found you discs from the an hour in her busy schedule to following catalogues: talk about this important new Prices include postage disc … and other things [Acte Préalable £13.50 ] [Arcodiva £12.00] [Avie from £6.25] Nick Barnard [NB]: In [British Music Society researching this interview it £12.00] [CDACCORD from £13.50 ] amazed me to realise that it is [ClassicO £12.50] now some twenty-one years [Hallé from £11] [Hortus £14.99 ] since your breakthrough [Lyrita ONLY £11.75 ] Berlin Philharmoniker Rattle recording. -

For All the Attention Paid to the Striking Passage of Thirty-Four

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Humanities Commons for Jane, on our thirty-fourth Accents of Remorse The good has never been perfect. There is always some flaw in it, some defect. First Sightings For all the attention paid to the “interview” scene in Benjamin Britten’s opera Billy Budd, its musical depths have proved remarkably resistant to analysis and have remained unplumbed. This striking passage of thirty-four whole-note chords has probably attracted more comment than any other in the opera since Andrew Porter first spotted shortly after the 1951 premiere that all the chords harmonize members of the F major triad, leading to much discussion over whether or not the passage is “in F major.” 1 Beyond Porter’s perception, the structure was far from obvious, perhaps in some way unprecedented, and has remained mysterious. Indeed, it is the undisputed gnomic power of its strangeness that attracted (and still attracts) most comment. Arnold Whittall has shown that no functional harmonic or contrapuntal explanation of the passage is satisfactory, and proceeded from there to make the interesting assertion that that was the point: The “creative indecision”2 that characterizes the music of the opera was meant to confront the listener with the same sort of difficulty as the layers of irony in Herman Melville’s “inside narrative,” on which the opera is based. To quote a single sentence of the original story that itself contains several layers of ironic ambiguity, a sentence thought by some—I believe mistakenly—to say that Vere felt no remorse: 1. -

Delius Monument Dedicatedat the 23Rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn

The Delius SocieQ JOUrnAtT7 Summer/Autumn1992, Number 109 The Delius Sociefy Full Membershipand Institutionsf 15per year USA and CanadaUS$31 per year Africa,Australasia and Far East€18 President Eric FenbyOBE, Hon D Mus.Hon D Litt. Hon RAM. FRCM,Hon FTCL VicePresidents FelixAprahamian Hon RCO Roland Gibson MSc, PhD (FounderMember) MeredithDavies CBE, MA. B Mus. FRCM, Hon RAM Norman Del Mar CBE. Hon D Mus VernonHandley MA, FRCM, D Univ (Surrey) Sir CharlesMackerras CBE Chairman R B Meadows 5 WestbourneHouse. Mount ParkRoad. Harrow. Middlesex HAI 3JT Ti,easurer [to whom membershipenquiries should be directed] DerekCox Mercers,6 Mount Pleasant,Blockley, Glos. GL56 9BU Tel:(0386) 700175 Secretary@cting) JonathanMaddox 6 Town Farm,Wheathampstead, Herts AL4 8QL Tel: (058-283)3668 Editor StephenLloyd 85aFarley Hill. Luton. BedfordshireLul 5EG Iel: Luton (0582)20075 CONTENTS 'The others are just harpers . .': an afternoon with Sidonie Goossens by StephenLloyd.... Frederick Delius: Air and Dance.An historical note by Robert Threlfall.. BeatriceHarrison and Delius'sCello Music by Julian Lloyd Webber.... l0 The Delius Monument dedicatedat the 23rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn........ t4 Fennimoreancl Gerda:the New York premidre............ l1 -Opera A Village Romeo anrl Juliet: BBC2 Season' by Henry Gi1es......... .............18 Record Reviews Paris eIc.(BSO. Hickox) ......................2l Sea Drift etc. (WNOO. Mackerras),.......... ...........2l Violin Concerto etc.(Little. WNOOO. Mackerras)................................22 Violin Concerto etc.(Pougnet. RPO. Beecham) ................23 Hassan,Sea Drift etc. (RPO. Beecham) . .-................25 THE HARRISON SISTERS Works by Delius and others..............26 A Mu.s:;r1/'Li.fe at the Brighton Festival ..............27 South-WestBranch Meetinss.. ........30 MicllanclsBranch Dinner..... ............3l Obittrary:Sir Charles Groves .........32 News Round-Up ...............33 Correspondence....... -

Britten Spring Symphony Welcome Ode • Psalm 150

BRITTEN SPRING SYMPHONY WELCOME ODE • PSALM 150 Elizabeth Gale soprano London Symphony Chorus Alfreda Hodgson contralto Martyn Hill tenor London Symphony Orchestra Southend Boys’ Choir Richard Hickox Greg Barrett Richard Hickox (1948 – 2008) Benjamin Britten (1913 – 1976) Spring Symphony, Op. 44* 44:44 For Soprano, Alto and Tenor solos, Mixed Chorus, Boys’ Choir and Orchestra Part I 1 Introduction. Lento, senza rigore 10:03 2 The Merry Cuckoo. Vivace 1:57 3 Spring, the Sweet Spring. Allegro con slancio 1:47 4 The Driving Boy. Allegro molto 1:58 5 The Morning Star. Molto moderato ma giocoso 3:07 Part II 6 Welcome Maids of Honour. Allegretto rubato 2:38 7 Waters Above. Molto moderato e tranquillo 2:23 8 Out on the Lawn I lie in Bed. Adagio molto tranquillo 6:37 Part III 9 When will my May come. Allegro impetuoso 2:25 10 Fair and Fair. Allegretto grazioso 2:13 11 Sound the Flute. Allegretto molto mosso 1:24 Part IV 12 Finale. Moderato alla valse – Allegro pesante 7:56 3 Welcome Ode, Op. 95† 8:16 13 1 March. Broad and rhythmic (Maestoso) 1:52 14 2 Jig. Quick 1:20 15 3 Roundel. Slower 2:38 16 4 Modulation 0:39 17 5 Canon. Moving on 1:46 18 Psalm 150, Op. 67‡ 5:31 Kurt-Hans Goedicke, LSO timpani Lively March – Lightly – Very lively TT 58:48 4 Elizabeth Gale soprano* Alfreda Hodgson contralto* Martyn Hill tenor* The Southend Boys’ Choir* Michael Crabb director Senior Choirs of the City of London School for Girls† Maggie Donnelly director Senior Choirs of the City of London School† Anthony Gould director Junior Choirs of the City of London School -

Emphasis on Female Conductors and Composers the Royal Concertgebouw Presents Its Programme for the 2018-2019 Season

Press release Emphasis on female conductors and composers The Royal Concertgebouw presents its programme for the 2018-2019 season Amsterdam, 26th February 2018 – For its programme for the 2018-2019 season, The Royal Concertgebouw has decided to put an emphasis on female conductors and composers. Together with the LUDWIG music collective, Barbara Hannigan is set to return to conduct her first opera, The Rake’s Progress by Stravinsky. For her Royal Concertgebouw debut, Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla will be bringing with her the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, of which she is chief conductor. Susanna Mälkki will also be heading her ‘very own’ Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra. It will also be the first time that The Royal Concertgebouw welcomes a female composer in residence, Tansy Davies, from Great Britain. She will reside in Amsterdam for a few months to, among other things, compose new works for Asko|Schönberg. In the Rising Stars series, the audience will hear commissioned works by Roxanna Panufnik and Camille Pépin, with attention also being paid to female composers such as Alma Mahler, Clara Schumann and Fanny Mendelssohn. The Italian composer and violinist Alba Rosa Viëtor will take centre stage during the one-day festival Alba Rosa Viva!. Her works will be supported by the works of Henriëtte Bosmans, Cécile Chaminade and Rosy Wertheim. Three female ‘Sharp thinkers’ are also set to make an appearance: Petra Stienen, Griet Op de Beeck and Aaltje van Zweden. Violinist Janine Jansen will display her versatility with three concerts in the Main Hall: in a recital together with pianist Alexander Gavrylyuk, and as a soloist with the Swedish Radio Orchestra and the Chamber Orchestra of Europe. -

Download Booklet

559199 bk Helps US 12/01/2004 11:54 am Page 8 Robert HELPS AMERICAN CLASSICS (1928-2001) ROBERT HELPS Shall We Dance Piano Quartet • Postlude • Nocturne Spectrum Concerts Berlin 8.559199 8 559199 bk Helps US 12/01/2004 11:54 am Page 2 Robert Helps (1928-2001) ROBERT HELPS (1928-2001) Shall We Dance • Piano Quartet • Postlude • Nocturne • The Darkened Valley (John Ireland) 1 Shall We Dance for Piano (1994) 11:09 Robert Helps was Professor of Music at the University of Minneapolis, and elsewhere. His later concerts included Piano Quartet for Piano, Violin, Viola and Cello (1997) 25:55 South Florida, Tampa, and the San Francisco memorial solo recitals of the music of renowned Conservatory of Music. He was a recipient of awards in American composer Roger Sessions at both Harvard and 2 I. Prelude 10:24 composition from the National Endowment for the Arts, Princeton Universities, an all-Ravel recital at Harvard, 3 II. Intermezzo 2:24 the Guggenheim, Ford, and many other foundations, and and a solo recital in Town Hall, NY. His final of a 1976 Academy Award from the Academy of Arts compositions include Eventually the Carousel Begins, for 4 III. Scherzo 3:02 and Letters. His orchestral piece Adagio for Orchestra, two pianos, A Mixture of Time for guitar and piano, which 5 IV. Postlude 8:12 which later became the middle movement of his had its première in San Francisco in June 1990 by Adam 6 V. Coda – The Players Gossip 1:53 Symphony No. 1, won a Fromm Foundation award and Holzman and the composer, The Altered Landscape was premièred by Leopold Stokowski and the Symphony (1992) for organ solo and Shall We Dance (1994) for 7 Postlude for Horn, Violin and Piano (1964) 9:11 of the Air (formerly the NBC Symphony) at the piano solo, Piano Trio No. -

Benjamin Britten: a Catalogue of the Orchestral Music

BENJAMIN BRITTEN: A CATALOGUE OF THE ORCHESTRAL MUSIC 1928: “Quatre Chansons Francaises” for soprano and orchestra: 13 minutes 1930: Two Portraits for string orchestra: 15 minutes 1931: Two Psalms for chorus and orchestra Ballet “Plymouth Town” for small orchestra: 27 minutes 1932: Sinfonietta, op.1: 14 minutes Double Concerto in B minor for Violin, Viola and Orchestra: 21 minutes (unfinished) 1934: “Simple Symphony” for strings, op.4: 14 minutes 1936: “Our Hunting Fathers” for soprano or tenor and orchestra, op. 8: 29 minutes “Soirees musicales” for orchestra, op.9: 11 minutes 1937: Variations on a theme of Frank Bridge for string orchestra, op. 10: 27 minutes “Mont Juic” for orchestra, op.12: 11 minutes (with Sir Lennox Berkeley) “The Company of Heaven” for two speakers, soprano, tenor, chorus, timpani, organ and string orchestra: 49 minutes 1938/45: Piano Concerto in D major, op. 13: 34 minutes 1939: “Ballad of Heroes” for soprano or tenor, chorus and orchestra, op.14: 17 minutes 1939/58: Violin Concerto, op. 15: 34 minutes 1939: “Young Apollo” for Piano and strings, op. 16: 7 minutes (withdrawn) “Les Illuminations” for soprano or tenor and strings, op.18: 22 minutes 1939-40: Overture “Canadian Carnival”, op.19: 14 minutes 1940: “Sinfonia da Requiem”, op.20: 21 minutes 1940/54: Diversions for Piano(Left Hand) and orchestra, op.21: 23 minutes 1941: “Matinees musicales” for orchestra, op. 24: 13 minutes “Scottish Ballad” for Two Pianos and Orchestra, op. 26: 15 minutes “An American Overture”, op. 27: 10 minutes 1943: Prelude and Fugue for eighteen solo strings, op. 29: 8 minutes Serenade for tenor, horn and strings, op. -

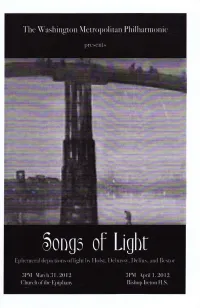

2012-0331 Program.Pdf

I\TI\OI)~I ClIO:-;~ Welcorne to Songs ofLight! JUSllikc the anists oftheir day, musicians ofthe Impressionistic CI"'J were intrigued with the cfTt.'C(S ofligtll and 50"0",11 to portray this in their music. With diminished light. the harsh cfTetts ofindustrialization were muted and these llt."\\ landst<q>cs Wert softened and made bc-Jutiful again. l1lis aftcmoon's program is filled wim ethereal depietions of light by Delius. Dehll"S)', and l-Io1st as well a~ with a sparkling new work by Charles Beslor. lei these airy musical work..<; lIallspon you to a time ofday where healilifulligiu softens the lrOublcs ofthe world bringingoullhe best ofany place. Enjo}! ,. As Illusie is lhe poetry OfSOlilld. so is paiming Ihe poclry ofsight. ~ - JUfIlt'JAblJOIf AfcNetillflllfJtler W:.ashillg'lotl Ml'tropolil.U1 rhilhanllonic. UI~"SSCS James. Music Dirt:('lOf & Condm:lor Ulys.<iCS S. James is a fonner lromhonist who studied in BOSlOll aud at Tauglcwood ..•..ith William Gibson. principal trombonist of the Bostoll Symphony On:heslra. He grddlllHcd in 1958 ....ith honurs in llIusi<: from Brown University. Mtcr a 20 yCM ~'aIttr as a surfoc-c ....~Mfare Naval Officer. followed by a second tareer as an organization and management de...e1opmem consultam. he bn-arne the music dire~1or and priocipal condtl~1or of Washington Metropolitan Philharmonic Association in 1985. The Assodation sponsors Washington Metropolitan Philharmonic. Washington ~lctropolitan YOUlh Orchestra. Washington Metropolitan Concen Orchestrd. a weekly summer chamber musie series at The Lyceum ill Old Towll Alexandria. and all anllual cOl1lpo~ition COllllletition for the Mid-Atlantic StUll'S. -

The Musical Partnership of Sergei Prokofiev And

THE MUSICAL PARTNERSHIP OF SERGEI PROKOFIEV AND MSTISLAV ROSTROPOVICH A CREATIVE PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF MUSIC IN PERFORMANCE BY JIHYE KIM DR. PETER OPIE - ADVISOR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA DECEMBER 2011 Among twentieth-century composers, Sergei Prokofiev is widely considered to be one of the most popular and important figures. He wrote in a variety of genres, including opera, ballet, symphonies, concertos, solo piano, and chamber music. In his cello works, of which three are the most important, his partnership with the great Russian cellist Mstislav Rostropovich was crucial. To understand their partnership, it is necessary to know their background information, including biographies, and to understand the political environment in which they lived. Sergei Prokofiev was born in Sontovka, (Ukraine) on April 23, 1891, and grew up in comfortable conditions. His father organized his general education in the natural sciences, and his mother gave him his early education in the arts. When he was four years old, his mother provided his first piano lessons and he began composition study as well. He studied theory, composition, instrumentation, and piano with Reinhold Glière, who was also a composer and pianist. Glière asked Prokofiev to compose short pieces made into the structure of a series.1 According to Glière’s suggestion, Prokofiev wrote a lot of short piano pieces, including five series each of 12 pieces (1902-1906). He also composed a symphony in G major for Glière. When he was twelve years old, he met Glazunov, who was a professor at the St. -

Gardiner's Schumann

Sunday 11 March 2018 7–9pm Barbican Hall LSO SEASON CONCERT GARDINER’S SCHUMANN Schumann Overture: Genoveva Berlioz Les nuits d’été Interval Schumann Symphony No 2 SCHUMANN Sir John Eliot Gardiner conductor Ann Hallenberg mezzo-soprano Recommended by Classic FM Streamed live on YouTube and medici.tv Welcome LSO News On Our Blog This evening we hear Schumann’s works THANK YOU TO THE LSO GUARDIANS WATCH: alongside a set of orchestral songs by another WHY IS THE ORCHESTRA STANDING? quintessentially Romantic composer – Berlioz. Tonight we welcome the LSO Guardians, and It is a great pleasure to welcome soloist extend our sincere thanks to them for their This evening’s performance of Schumann’s Ann Hallenberg, who makes her debut with commitment to the Orchestra. LSO Guardians Second Symphony will be performed with the Orchestra this evening in Les nuits d’été. are those who have pledged to remember the members of the Orchestra standing up. LSO in their Will. In making this meaningful Watch as Sir John Eliot Gardiner explains I would like to take this opportunity to commitment, they are helping to secure why this is the case. thank our media partners, medici.tv, who the future of the Orchestra, ensuring that are broadcasting tonight’s concert live, our world-class artistic programme and youtube.com/lso and to Classic FM, who have recommended pioneering education and community A warm welcome to this evening’s LSO tonight’s concert to their listeners. The projects will thrive for years to come. concert at the Barbican, as we are joined by performance will also be streamed live on WELCOME TO TONIGHT’S GROUPS one of the Orchestra’s regular collaborators, the LSO’s YouTube channel, where it will lso.co.uk/legacies Sir John Eliot Gardiner. -

Britten Connections a Guide for Performers and Programmers

Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Britten –Pears Foundation Telephone 01728 451 700 The Red House, Golf Lane, [email protected] Aldeburgh, Suffolk, IP15 5PZ www.brittenpears.org Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Contents The twentieth century’s Programming tips for 03 consummate musician 07 13 selected Britten works Britten connected 20 26 Timeline CD sampler tracks The Britten-Pears Foundation is grateful to Orchestra, Naxos, Nimbus Records, NMC the following for permission to use the Recordings, Onyx Classics. EMI recordings recordings featured on the CD sampler: BBC, are licensed courtesy of EMI Classics, Decca Classics, EMI Classics, Hyperion Records, www.emiclassics.com For full track details, 28 Lammas Records, London Philharmonic and all label websites, see pages 26-27. Index of featured works Front cover : Britten in 1938. Photo: Howard Coster © National Portrait Gallery, London. Above: Britten in his composition studio at The Red House, c1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton . 29 Further information Opposite left : Conducting a rehearsal, early 1950s. Opposite right : Demonstrating how to make 'slung mugs' sound like raindrops for Noye's Fludde , 1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton. Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers 03 The twentieth century's consummate musician In his tweed jackets and woollen ties, and When asked as a boy what he planned to be He had, of course, a great guide and mentor. with his plummy accent, country houses and when he grew up, Britten confidently The English composer Frank Bridge began royal connections, Benjamin Britten looked replied: ‘A composer.’ ‘But what else ?’ was the teaching composition to the teenage Britten every inch the English gentleman. -

Repertoire List

APPROVED REPERTOIRE FOR 2022 COMPETITION: Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Repertoire substitution requests will be considered by the Charlotte Symphony on an individual case-by-case basis. The deadline for all repertoire approvals is September 15, 2021. Please email [email protected] with any questions. VIOLIN VIOLINCELLO J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor BOCCHERINI All cello concerti Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DVORAK Cello Concerto in B Minor BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major Romance No. 2 in F Major HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor LALO Cello Concerto in D Minor HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major SAINT-SAENS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Minor LALO Symphonie Espagnole for Violin SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor DOUBLE BASS MONTI Czárdás BOTTESINI Double Bass Concerto No. 2in B Minor MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 DITTERSDORF Double Bass Concerto in E Major PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor DRAGONETTI All double bass concerti SAINT-SAENS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso KOUSSEVITSKY Double Bass Concerto in F# Minor Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor HARP SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin and Strings DEBUSSY Danses Sacrée et Profane (in entirety) SIBELIUS Violin Concerto in D Minor DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major VIVALDI The Four Seasons HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op.