Indig Pop Resource Flows.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Driving Holidays in the Northern Territory the Northern Territory Is the Ultimate Drive Holiday Destination

Driving holidays in the Northern Territory The Northern Territory is the ultimate drive holiday destination A driving holiday is one of the best ways to see the Northern Territory. Whether you are a keen adventurer longing for open road or you just want to take your time and tick off some of those bucket list items – the NT has something for everyone. Top things to include on a drive holiday to the NT Discover rich Aboriginal cultural experiences Try tantalizing local produce Contents and bush tucker infused cuisine Swim in outback waterholes and explore incredible waterfalls Short Drives (2 - 5 days) Check out one of the many quirky NT events A Waterfall hopping around Litchfield National Park 6 Follow one of the unique B Kakadu National Park Explorer 8 art trails in the NT C Visit Katherine and Nitmiluk National Park 10 Immerse in the extensive military D Alice Springs Explorer 12 history of the NT E Uluru and Kings Canyon Highlights 14 F Uluru and Kings Canyon – Red Centre Way 16 Long Drives (6+ days) G Victoria River region – Savannah Way 20 H Kakadu and Katherine – Nature’s Way 22 I Katherine and Arnhem – Arnhem Way 24 J Alice Springs, Tennant Creek and Katherine regions – Binns Track 26 K Alice Springs to Darwin – Explorers Way 28 Parks and reserves facilities and activities 32 Festivals and Events 2020 36 2 Sealed road Garig Gunak Barlu Unsealed road National Park 4WD road (Permit required) Tiwi Islands ARAFURA SEA Melville Island Bathurst VAN DIEMEN Cobourg Island Peninsula GULF Maningrida BEAGLE GULF Djukbinj National Park Milingimbi -

A Twentieth-Century Aboriginal Family

Chapter 10 The Northern Territory, 1972 The 1972 Federal election was a time of heightened tension among interest groups in Australia. The Liberal-Country Party coalition had been in power since 1949 and all politically minded people sensed a change. All except those in power. Aboriginal poverty, high infant mortality rates and the question of Land Rights left Aboriginal leaders wondering how they could contribute in the political milieu they were confronted with. Charlie Perkins had been telling me for three or four years that he wanted to ‘get rid of this government’, in particular to show his contempt for the Country Party. Charlie at the time was an Assistant Secretary in the Department of Aboriginal Affairs and in spite of his role as a bureaucrat he was intimately involved in Aboriginal politics. So was I. On many occasions he would express his confidence that change in Aboriginal people’s living conditions were just around the corner while at other times he would be filled with despair. The time frame between accepting the nomination to run for the Northern Territory seat and leaving Sydney was very tight. As a family we had to sell the Summer Hill house to finance getting to, and living in Alice Springs. I had to resign from the Legal Service, make contact with the Australia Party base in Darwin and prepare my thinking for an election campaign. One of the first things I did was to speak to my colleague Len Smith to seek his views about if, and how, I should run my campaign. -

Infrastructure Requirements to Develop Agricultural Industry in Central Australia

Submission Number: 213 Attachment C INFRASTRUCTURE REQUIREMENTS TO DEVELOP AGRICULTURAL INDUSTRY IN CENTRAL AUSTRALIA 132°0'0"E 133°0'0"E 134°0'0"E 135°0'0"E 136°0'0"E 137°0'0"E Aboriginal Potential Potential Approximate Bore Field & Water Control Land Trust Water jobs when direct Infrastructure District (ALT) / Allocation fully economic Requirements Area (ML) developed value ($m) ($m) Karlantijpa 1000 20 Tennant ALT Creek + Warumungu $12m $3.94m Frewena ALT 2000 40 (Frewena) 19°0'0"S Frewena 19°0'0"S LIKKAPARTA Tennant Creek Karlantijpa ALT Potential Potential Approximate Bore Field & Water Aboriginal Control Land Trust Water jobs when direct Infrastructure District (ALT) / Area Allocation fully economic Requirements 20°0'0"S (ML) developed value ($m) ($m) 20°0'0"S Illyarne ALT 1500 30 Warrabri ALT 4000 100 $2.9m Western MUNGKARTA Murray $26m (Already Davenport Downs & invested via 1000 ABA $3.5m) Singleton WUTUNUGURRA Station CANTEEN CREEK Illyarne ALT Murray Downs and Singleton Stations ALI CURUNG 21°0'0"S 21°0'0"S WILLOWRA TARA Warrabri ALT AMPILATWATJA WILORA Ahakeye ALT (Community farm) ARAWERR IRRULTJA 22°0'0"S NTURIYA 22°0'0"S PMARA JUTUNTA YUENDUMU YUELAMU Ahakeye ALT (Adelaide Bore) A Potential Potential Approximate Bore Field & B Water LARAMBA Control Aboriginal Land Water jobs when direct Infrastructure C District Trust (ALT) / Area Allocation fully economic Requirements Ahakeye ALT (6 Mile farm) (ML) developed value ($m) ($m) Ahakeye ALT Pine Hill Block B ENGAWALA community farm 30 5 ORRTIPA-THURRA Adelaide bore 1000 20 Ti-Tree $14.4m $3.82m Ahakeye ALT (Bush foods precinct) Pine Hill ‘B’ 1800 20 BushfoodsATITJERE precinct 70 5 6 mile farm 400 10 23°0'0"S 23°0'0"S PAPUNYA Potentia Potential Approximate Bore Field & HAASTS BLUFF Water Aboriginal Control Land Trust l Water jobs when direct Infrastructure District (ALT) / Area Allocati fully economic Requirements on (ML) developed value ($m) ($m) A.S. -

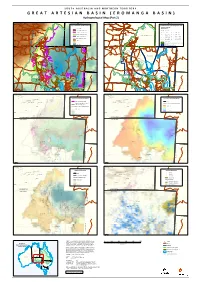

GREAT ARTESIAN BASIN Responsibility to Any Person Using the Information Or Advice Contained Herein

S O U T H A U S T R A L I A A N D N O R T H E R N T E R R I T O R Y G R E A T A R T E S I A N B A S I N ( E RNturiyNaturiyaO M A N G A B A S I N ) Pmara JutPumntaara Jutunta YuenduYmuuendumuYuelamu " " Y"uelamu Hydrogeological Map (Part " 2) Nyirri"pi " " Papunya Papunya ! Mount Liebig " Mount Liebig " " " Haasts Bluff Haasts Bluff ! " Ground Elevation & Aquifer Conditions " Groundwater Salinity & Management Zones ! ! !! GAB Wells and Springs Amoonguna ! Amoonguna " GAB Spring " ! ! ! Salinity (μ S/cm) Hermannsburg Hermannsburg ! " " ! Areyonga GAB Spring Exclusion Zone Areyonga ! Well D Spring " Wallace Rockhole Santa Teresa " Wallace Rockhole Santa Teresa " " " " Extent of Saturated Aquifer ! D 1 - 500 ! D 5001 - 7000 Extent of Confined Aquifer ! D 501 - 1000 ! D 7001 - 10000 Titjikala Titjikala " " NT GAB Management Zone ! D ! Extent of Artesian Water 1001 - 1500 D 10001 - 25000 ! D ! Land Surface Elevation (m AHD) 1501 - 2000 D 25001 - 50000 Imanpa Imanpa ! " " ! ! D 2001 - 3000 ! ! 50001 - 100000 High : 1515 ! Mutitjulu Mutitjulu ! ! D " " ! 3001 - 5000 ! ! ! Finke Finke ! ! ! " !"!!! ! Northern Territory GAB Water Control District ! ! ! Low : -15 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! FNWAP Management Zone NORTHERN TERRITORY Birdsville NORTHERN TERRITORY ! ! ! Birdsville " ! ! ! " ! ! SOUTH AUSTRALIA SOUTH AUSTRALIA ! ! ! ! ! ! !!!!!!! !!!! D !! D !!! DD ! DD ! !D ! ! DD !! D !! !D !! D !! D ! D ! D ! D ! D ! !! D ! D ! D ! D ! DDDD ! Western D !! ! ! ! ! Recharge Zone ! ! ! ! ! ! D D ! ! ! ! ! ! N N ! ! A A ! L L ! ! ! ! S S ! ! N N ! ! Western Zone E -

Centring Anangu Voices

Report NR005 2017 Centring Anangu Voices A research project exploring how Nyangatjatjara College might better strengthen Anangu aspirations through education Sam Osborne John Guenther Lorraine King Karina Lester Sandra Ken Rose Lester Cen Centring Anangu Voices A research project exploring how Nyangatjatjara College might better strengthen Anangu aspirations through education. December 2017 Research conducted by Ninti One Ltd in conjunction with Nyangatjatjara College Dr Sam Osborne, Dr John Guenther, Lorraine King, Karina Lester, Sandra Ken, Rose Lester 1 Executive Summary Since 2011, Nyangatjatjara College has conducted a series of student and community interviews aimed at providing feedback to the school regarding student experiences and their future aspirations. These narratives have developed significantly over the last seven years and this study, a broader research piece, highlights a shift from expressions of social and economic uncertainty to narratives that are more explicit in articulating clear directions for the future. These include: • A strong expectation that education should engage young people in training and work experiences as a pathway to employment in the community • Strong and consistent articulation of the importance of intergenerational engagement to 1. Ground young people in their stories, identity, language and culture 2. Encourage young people to remain focussed on positive and productive pathways through mentoring 3. Prepare young people for work in fields such as ranger work and cultural tourism • Utilise a three community approach to semi-residential boarding using the Yulara facilities to provide access to expert instruction through intensive delivery models • Metropolitan boarding programs have realised patchy outcomes for students and families. The benefits of these experiences need to be built on through realistic planning for students who inevitably return (between 3 weeks and 18 months from commencement). -

Calendar of Events Unsafe Areas for Spectators

CALENDAR UNSAFE AREAS BUILD A EXTINGUISH OF EVENTS FOR SPECTATORS SAFE FIRE A CAMP FIRE Make sure there is a 4 x 4 metre clearing Remove slow burning logs and completely extuingish with water WHAT, WHERE & WHEN OF FINKE RACING VEHICLES CAN OVERSHOOT. Dig a hole about 90 cm in diameter and 30 cm State of Origin Screening - 6:00pm deep Shovel the boundary soil over the fire to completely cover it Wednesday 9th June - Lasseters Casino Use the soil that you have removed to make a Finke Street Party & Night Markets - 5:00pm FOR YOUR SAFETY WE INSIST YOU DON’T boundary for the fire Never leave a burning fire unattended Thursday 10th June - Todd Mall STAND/CAMP IN THE MARKED AREAS Build your fire in the hole Ensure all campfires are extinguished before Scrutineering - 4:00pm leaving the campsite Friday 11th June - Start/Finish Line Precinct Have some water nearby Prologue - 7:30am Saturday 12th June - Start/Finish Line Precinct Race Day 1 - 7:00am Under Section 74 of the Bushres Management Act Sunday 13th June - Start/Finish Line Precinct TIGHT CORNERS KEEP LEFT OR RIGHT 2016 (NT) if is an oence if a person leaves a re Race Day 2 - 7:30am unattended. Monday 14th June - Start/Finish Line Precinct No standing & camping zone No standing & camping zone Presentation Night - 6:30pm 4 Meters 90 cm 4 Meters Maximum penalty 500 penalty units or 5 years Monday 14th June - A/S Convention Centre imprisonment (1 penalty unit = $155) TIGHT CORNERS TURN AT CROSS ROAD MERCHANDISE No standing & camping zone No standing & camping zone ADMISSION FINKE -

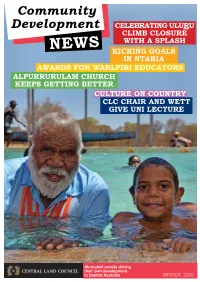

Community Development

Community Development CELEBRATING ULURU CLIMB CLOSURE WITH A SPLASH NEWS KICKING GOALS IN NTARIA AWARDS FOR WARLPIRI EDUCATORS ALPURRURULAM CHURCH KEEPS GETTING BETTER CULTURE ON COUNTRY CLC CHAIR AND WETT GIVE UNI LECTURE Aboriginal people driving their own development in Central Australia WINTER 2020 ANANGU CELEBRATE ULURU CLIMB 2 CLOSURE AND COMMUNITY PROJECTS Ngoi Ngoi Donald talking Anangu have used the Uluru climb with ABC journalist and closure to show off what they have CLC staff Patrick Hookey. achieved with their share of the national park’s gate money. On the afternoon before the celebration, “THAT MONEY, WE USE IT doubt about the pool’s popularity. traditional owners gave politicians, senior EVERYWHERE FOR GOOD The families visiting Mutitjulu for the climb public servants and selected media a special ONES: SWIMMING POOL, closure celebration and the midday heat tour of Mutitjulu’s pool and surrounding helped boost the number of swimmers. recreation area. BUSH TRIPS, DIALYSIS, LOTS OF GOOD THINGS Elder Reggie Uluru swapped his wheel chair The chief executive of the National Indigenous for a special lift to cool off in the pool with his Australians Agency, Ray Griggs and some of FOR COMMUNITY,” MS grandson Andre. his colleagues, then NT opposition leader Gary DONALD SAID. He was back refreshed as night descended Higgins and journalists from the ABC and the CLC chief executive Joe Martin-Jard and on Talinguru Nyakunytjaku (the sunrise Guardian learned that the project has so far community development manager Ian Sweeney viewing area), beating out the rhythm with invested 14 million dollars in more than 100 talked about the history, governance and future two ceremonial boomerangs as Anangu projects in communities across the region. -

MS 5014 C.D. Rowley, Study of Aborigines in Australian Society, Social Science Research Council of Australia: Research Material and Indexes, 1964-1968

AIATSIS Collections Catalogue Manuscript Finding Aid Index Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Library MS 5014 C.D. Rowley, Study of Aborigines in Australian Society, Social Science Research Council of Australia: research material and indexes, 1964-1968 CONTENTS COLLECTION SUMMARY………………………………………….......page 5 CULTURAL SENSITIVITY STATEMENT……………………………..page 5 ACCESS TO COLLECTION………………………………………….…page 6 COLLECTION OVERVIEW……………………………………………..page 7 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE………………………………...………………page 10 SERIES DESCRIPTION………………………………………………...page 12 Series 1 Research material files Folder 1/1 Abstracts Folder 1/2 Agriculture, c.1963-1964 Folder 1/3 Arts, 1936-1965 Folder 1/4 Attitudes, c.1919-1967 Folder 1/5 Bibliographies, c.1960s MS 5014 C.D. Rowley, Study of Aborigines in Australian Society, Social Science Research Council of Australia: research material and indexes, 1964-1968 Folder 1/6 Case Histories, c.1934-1966 Folder 1/7 Cooperatives, c.1954-1965. Folder 1/8 Councils, 1961-1966 Folder 1/9 Courts, Folio A-U, 1-20, 1907-1966 Folder 1/10-11 Civic Rights, Files 1 & 2, 1934-1967 Folder 1/12 Crime, 1964-1967 Folder 1/13 Customs – Native, 1931-1965 Folder 1/14 Demography – Census 1961 – Australia – full-blood Aboriginals Folder 1/15 Demography, 1931-1966 Folder 1/16 Discrimination, 1921-1967 Folder 1/17 Discrimination – Freedom Ride: press cuttings, Feb-Jun 1965 Folder 1/18-19 Economy, Pts.1 & 2, 1934-1967 Folder 1/20-21 Education, Files 1 & 2, 1936-1967 Folder 1/22 Employment, 1924-1967 Folder 1/23 Family, 1965-1966 -

Family News 67

Family News Edition 67 Lexi Ward from Aputula and story on pg4 © Waltja Tjutangku Palyapayi Aboriginal Corporation “ doing good work with families” Postal: PO Box 8274 Alice Springs NT 0871 Location: 3 Ghan Rd Alice Springs NT 0870 Ph: (08) 8953 4488 Fax: (08) 89534577 Website: www.waltja.org.au Waltja Chairperson 2020ngka ngarangu watjil, watjilpa, tjilura, tjiluru nganampa Waltja tjutaku. Ngurra tjutanya patirringu marrkunutjananya ngurrangka nyinanytjaku wiya tawunukutu ngalya yankutjaku. Tjananya watjanu wiya, ngaanyakuntjaku Waltja kutjupa tjutangku tjana patikutu nyinangi Waltjangku, katjangku, yuntalpanku, tjamuku nyaakuntja wiya. Ngurra purtjingka nyinapaiyi tjutanya, Kapumantaku marrkunu tjananya nyinantjaku ngurrangka Tjanaya watjil watjilpa, nyinangi wiya nganana yuntjurringnyi tawunukatu yankutjaku mangarriku, yultja mantjintjaku Waltjalu? Tjanampa yiyanangi yultja tjuta ngurra winkikutu. Tjana yunparringu ngurra winkinya mangarriku Walytjalu yiyanutjangka. Walytjalu yilta tjananya puntura alpamilaningi. Panya Sharijnlu watjanutjangka. Yanangi warrkana tjutanya ngurra tjutakutu. Youth worker, NDIS, culture anta governance tjuta warrkanarripanya Walytjaku kimiti tjutanyalatju tjungurrikula miitingingka wankangi 12 times Member tjutangku miitingingka wangkangi AGM miitingi. Panya minta kuyangkulampa yangatjunu. AGM miitingi ngaraku March-tjingka (2021-ngngka) Nganana yuntjurrinyi minmya tjutaku ngurra tjutaku. Yukarraku, Ulkumanuku, nganana yuntjurringanyi. Palyaya nyinama ngurrangka Walytja tjuta kunpurringamaya. Palya Nangala. 2020 was a hard year, a sad year for people. The remote communities were locked down and no visiting each other. No shopping in Alice Springs. Everyone was crying for warm clothes and food. Oh we were too busy at Waltja clothes and food everywhere! Sending to every community. The rest of the year we were working with Sharijn to do all the programs, help the workers to go bush. Youth work, NDIS, culture and governance work. -

Public Leadership—Perspectives and Practices

Public Leadership Perspectives and Practices Public Leadership Perspectives and Practices Edited by Paul ‘t Hart and John Uhr Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/public_leadership _citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Public leadership pespectives and practices [electronic resource] / editors, Paul ‘t Hart, John Uhr. ISBN: 9781921536304 (pbk.) 9781921536311 (pdf) Series: ANZSOG series Subjects: Leadership Political leadership Civic leaders. Community leadership Other Authors/Contributors: Hart, Paul ‘t. Uhr, John, 1951- Dewey Number: 303.34 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by John Butcher Images comprising the cover graphic used by permission of: Victorian Department of Planning and Community Development Australian Associated Press Australian Broadcasting Corporation Scoop Media Group (www.scoop.co.nz) Cover graphic based on M. C. Escher’s Hand with Reflecting Sphere, 1935 (Lithograph). Printed by University Printing Services, ANU Funding for this monograph series has been provided by the Australia and New Zealand School of Government Research Program. This edition © 2008 ANU E Press John Wanna, Series Editor Professor John Wanna is the Sir John Bunting Chair of Public Administration at the Research School of Social Sciences at The Australian National University. He is the director of research for the Australian and New Zealand School of Government (ANZSOG). -

Central Australian Youth Link-Up Service

P: 08 8951 4236 F: 08 8952 8521 PO Box 8070, Alice Springs, NT 0871 www.caylus.org.au The Executive Director Australian Law Reform Commission GPO Box 3708 SYDNEY NSW 2001 31 August 2017 Re: Submission to The Inquiry into Incarceration rates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples To the Executive Director, We are writing to bring some recently completed research to the attention of your inquiry. The attached report: Investing in the future; the impact of youth programs in remote central Australia: a Social Return on Investment (SROI) analysis was facilitated by CAYLUS and conducted by the Nous Group as a part of their community benefit work. This research comprehensively examines three youth programs in three remote communities in the NT. These programs range from a relatively new program that runs on very minimal funding through to program that has operated for 25 years, that has grown in complexity and which has attracted a greater level of funding. As shown in the research these types of programs primary value is that they keep young people busy and prevent risky behaviours by young people before they happen. As such we draw this research to your attention in relation to the Inquiries terms of reference 2 e iii the availability and effectiveness of culturally appropriate programs that intend to reduce Aboriginal; and Torres Strait Islander offending and incarceration. The research also shows that these programs play a role in Decreasing Detention through Use of Community Supervision and Decreasing Contact with Police both of which arguably relate to a range of other terms of reference. -

Footy Feats “Wiya” Attack

FREE November 2014 VOLUME 4. NUMBER 2. DESERT SEVENZ WIN PG. 24 MINING WATARRKA LAND RIGHTS FOOTY FEATS “WIYA” ATTACK PG. 6 PG. 2 PG. 34 ISSN 1839-5279 page1.indd 1 17/10/2014 9:47:20 AM NEWS EDITORIAL Land Rights News Central Australia is published by the Central Land Council three times a year. The Central Land Council 27 Stuart Hwy Alice Springs NT 0870 tel: 89516211 www.clc.org.au email [email protected] Contributions are welcome SUBSCRIPTIONS Land Rights News Central Australia subscriptions are $20 per annum. LRNCA is distributed free to Aboriginal organisations and communities in Central Meet the leaders Australia To subscribe email: [email protected] ADVERTISING AFTER almost a year of turmoil the nesses.” Community Council and served on the Central Land Council is under new lead- He is well known for the documenta- boards of the NT Grants Commission and Advertise in the only ership. ries Coniston and Aboriginal Rules, as National Indigenous Television (NITV). The CLC delegates elected Yuendu- well as the Bush Mechanics television He is a member of Yuendumu’s Gran- newspaper to reach mu fi lm maker Francis Jupururrla Kelly, series and hopes to combine his new role ites Mine Aff ected Areas Aboriginal Cor- 62, as the new CLC chair at their special with work on fi lms about the stolen gen- poration (GMAAAC) committee, which Aboriginal people meeting in Tennant Creek in July. erations and Olive Pink. uses compensation income for communi- in remote Central A former deputy chair, Mr Kelly said Mr Kelly has been a strong voice in ty benefi t projects.